FINA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

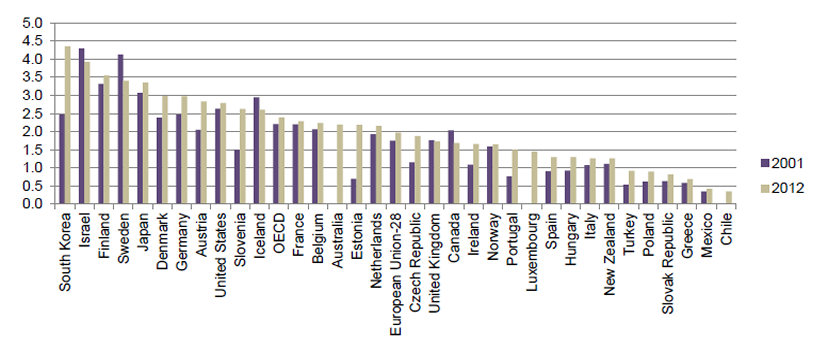

CHAPTER FOUR: INCREASING THE COMPETITIVENESS OF CANADIAN BUSINESSES THROUGH RESEARCH, DEVELOPMENT, INNOVATION AND COMMERCIALIZATIONA. BackgroundThe Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines the term “research and development” (R&D) as “[a]ny creative systematic activity undertaken in order to increase the stock of knowledge, including knowledge of man, culture and society, and the use of this knowledge to devise new applications.” It includes basic and applied research, as well as experimental development. According to the OECD, the term “basic research” is defined as “experimental or theoretical work undertaken primarily to acquire new knowledge of the underlying foundations of phenomena and observable facts, without any particular application or use in view”; the term “applied research” is defined as “original investigation undertaken in order to acquire new knowledge. It is, however, directed primarily towards a specific practical aim or objective.” Finally, the OECD considers experimental development to be “systematic work, drawing on existing knowledge gained from research and/or practical experience, that is directed to producing new materials, products or devices; to installing new processes, systems and services; or to improving substantially those already produced or installed.” In the view of the Canada Business Network, innovation refers to finding creative new ways to solve problems, react to change or produce something better. In the business context, innovation enables new or improved goods or services to be produced, licensed or sold; as well, processes that reduce production costs while improving productivity can be developed. Finally, innovation helps businesses to improve their ability to compete in Canadian and global markets. Commercialization, which is characterized as one of the most difficult steps in the innovation process because it is resource-intensive, refers to the introduction of new goods or services into the marketplace. Figure 5 presents gross domestic expenditures on R&D in selected countries as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) for 2001 and 2012. For the average of OECD countries, this percentage rose from 2.21% in 2001 to 2.40% in 2012; however, the percentage for Canada fell from 2.04% in 2001 to 1.70% in 2012. Figure 5 – Gross Domestic Expenditures on Research and Development as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product, Selected Countries, 2001 and 2012 (%)

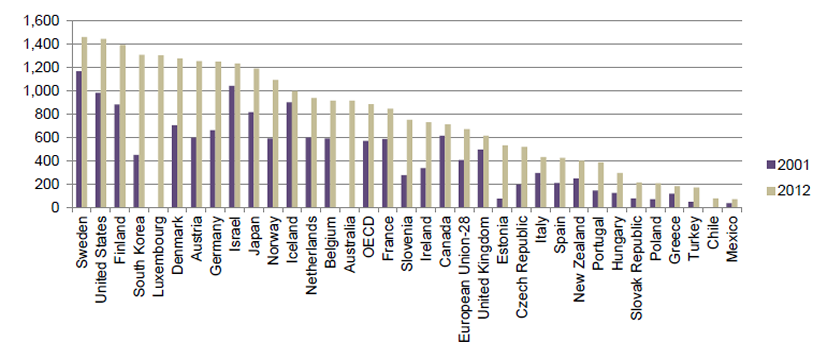

Note: For Australia, the latest available data are for 2010. For Iceland, Mexico and New Zealand, the latest available data are for 2011. Source: Figure prepared using data from: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Gross Domestic Expenditure on Research and Development as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product,” Main Science and Technology Indicators Database, accessed 27 October 2014. Figure 6 shows per capita gross domestic expenditures on R&D in 2001 and 2012 for selected countries; the expenditures are presented in current dollars, adjusted for purchasing power parity. Per capita expenditures for the average of OECD countries grew by 55.2% from 2001 to 2012, rising from $569 to $883. With per capita expenditures of $613 in 2001, Canada exceeded the OECD average; however, with an increase of 16.0% between 2001 and 2012, these expenditures – at $711 – were, in 2012, 19% lower than the OECD average. Figure 6 – Per Capita Gross Domestic Expenditures on Research and Development, Selected Countries, 2001 and 2012 (current $, adjusted for purchasing power parity)

Notes: For Australia, the latest available data are for 2010. For Iceland, Mexico and New Zealand, the latest available data are for 2011.

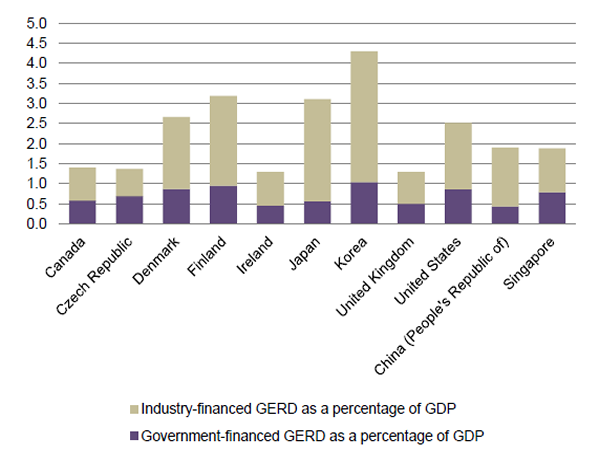

Source: Figure prepared using data from: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Gross Domestic Expenditure on Research and Development Per Capita Population (current PPP $),” Main Science and Technology Indicators Database, accessed 27 October 2014. Figure 7 shows, for 2012, gross domestic expenditures on R&D as a percentage of GDP by governments and by the private sector in selected countries. In almost all of these countries, R&D expenditures by the private sector exceeded such expenditures by governments in that year. Figure 7 – Gross Domestic Expenditures on Research and Development as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product, by Source, Selected Countries, 2012 (%)

Notes: For the United States, gross expenditures do not include capital expenditures and all state government expenditures.

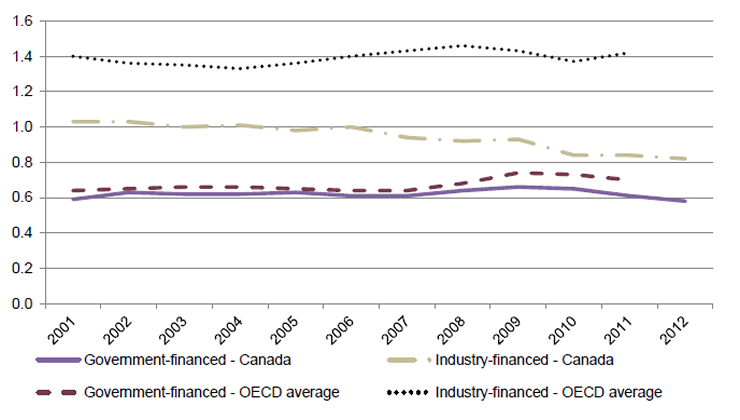

Source: Figure prepared using data from: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Main Science and Technology Indicators Database, accessed 27 November 2014. Figure 8 shows, for Canada and the OECD average, gross domestic expenditures on R&D as a percentage of GDP by governments and by the private sector over the 2001–2012 period. In Canada, the percentage for the private sector fell from 1.03% in 2001 to 0.82% in 2012, while that for governments was relatively stable. Figure 8 – Gross Domestic Expenditures on Research and Development as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product, by Source, Canada and OECD Countries, 2001–2012 (%)

Note: For the OECD average, the latest available data are for 2011. Source: Figure prepared using data from: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Main Science and Technology Indicators Database, accessed 27 November 2014. In Canada, tax measures – such as the Scientific Research & Experimental Development investment tax credit – and the activities of the federal granting councils – the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research – are examples of federal support for basic and applied research, as well as experimental development. As well, there are a range of programs and other initiatives – including the Centres of Excellence for Commercialization and Research, as well as the National Research Council–Industrial Research Assistance Program – that support commercialization. B. Changes Proposed by Witnesses Invited to Address “Increasing the Competitiveness of Canadian Businesses Through Research, Development, Innovation and Commercialization”Witnesses invited by the Committee to speak about the topic of increasing the competitiveness of Canadian businesses through research, development, innovation and commercialization advocated tax measures, federal funding, and other supports and measures. 1. Tax MeasuresClean Energy Canada called for an expansion of capital cost allowance Classes 43.1 and 43.2 to include photovoltaics, investments that are designed to make buildings solar-panel ready, and power storage technologies. In commenting that the 2012 changes to the Scientific Research and Experimental Development investment tax credit reduced the incentive to undertake new R&D in Canada, the Canadian Vehicle Manufacturers’ Association discussed the need to make the investment tax credit more competitive with incentives offered in other jurisdictions. The Information Technology Association of Canada suggested an increase in the tax rate on expenditures that qualify for the investment tax credit from 15% to 17%, as well as a reversal of the decision to exclude capital expenditures from eligible deductible Scientific Research and Experimental Development expenses. Canadian Manufacturers & Exporters called for unused Scientific Research and Experimental Development tax credits to be converted to a direct expenditure program that would support R&D and could assist small manufacturing companies facing difficulties with product development. The Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada proposed renewal of the Mineral Exploration Tax Credit for an additional three years. 2. Federal FundingIn relation to federal funding, witnesses advocated increased funding for federal granting councils, as well as for existing funds or initiatives, and the creation of new measures in specific areas. Polytechnics Canada noted that the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada’s College and Community Innovation Program is the Council’s only program that supports applied research at the college level, and proposed more funding for that program. As well, it asked for increased funding for the indirect costs of research programs, and for the College and Community Innovation Program to be eligible for that funding. While highlighting the importance of investments in fundamental basic research to maintain research excellence, the U15 Group of Canadian Research Universities advocated predictable and sustained funding for the three federal granting councils and the Canada Foundation for Innovation. The Canadian Vehicle Manufacturers’ Association suggested that repayable loans provided to automotive firms under the Automotive Innovation Fund be non-repayable and, in supporting Canadian incentives that are comparable to those in other jurisdictions, it proposed that some aspects of that fund – such as its taxation rules – be modified. The Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada asked that funding for the Targeted Geoscience Initiative be maintained and that the initiative be renewed for an additional five years. It also proposed that this initiative include more participation by industry at the planning and design stages, and advocated higher discovery rates as an explicit objective of the initiative. The Canadian Water Network called for funding of $60 million over 10 years to support R&D, with this investment attracting funds from businesses and other levels of government. The Forest Products Association of Canada advocated the creation of a $60 million fund over five years to support R&D activities conducted in universities and colleges. It also suggested that Sustainable Development Technology Canada’s NextGen Biofuels Fund be changed to a biorefinery fund that would be available to a wider range of sectors, including forestry, agriculture, biochemical, textile and biofuel. In highlighting the limited research in Canada regarding the development of energy-efficient products and technologies, the Canada Green Building Council proposed federal investments in commercialization activities in relation to those products. Downsview Aerospace Innovation and Research requested funding of $60 million over five years to transform the existing facilities at Downsview Park into an aerospace hub. As well, in its brief, it suggested that Canada Lands Company be given the mandate to work with it under the terms of a public-private partnership to develop this hub. The Canadian Rare Earth Element Network asked for funding of $25 million over five years to leverage Canada’s rare earth resource position and reputation, improve international trade, develop highly qualified personnel, and create and sustain jobs. In its brief, TRIUMF advocated funding of $68 million over five years to strengthen business competitiveness in isotope R&D, nuclear medicine and materials science. In particular, it mentioned the establishment of a laboratory – Canada’s accelerator platform to unleash research excellence, or CAPTURE – that would support TRIUMF’s work and the completion of its new facility, which is called the Advanced Rare IsotopE Laboratory, or ARIEL. Co-operatives and Mutuals Canada proposed funding of $50 million for the Canadian Co-operative Investment Fund that is being created by the co-operative sector to foster innovation, as well as to support small- and medium-sized businesses and co‑operatives. The National Angel Capital Organization called for funding of $5 million over three years for the implementation of a mobilization campaign to create awareness about angel investing among private investors. As well, it encouraged the creation of mechanisms that support the growth of companies that receive investments. The Société de promotion économique de Rimouski requested assistance to build networks among researchers, academic institutions and businesses in the marine biotechnology sector, which could help researchers obtain funding for the commercialization of their research. 3. Other Supports and MeasuresWitnesses spoke about types of support unrelated to taxation or program spending, as well as other measures that they believe would lead to R&D, innovation and/or commercialization. The Canadian Vehicle Manufacturers’ Association proposed the creation of a Canadian automotive research institute that would support research, development, innovation and commercialization of new products and manufacturing processes relating to the automobile sector. The Confédération des syndicats nationaux highlighted the need for the government to develop an industrial strategy, with infrastructure investments that would promote and support the manufacturing sector. Canada’s Research-Based Pharmaceutical Companies advocated more accurate reporting by the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board on R&D conducted by Canada’s pharmaceutical industry. Clean Energy Canada called for a federal rebate of up to $7,500 for the purchase of electric vehicles; this rebate level would be comparable to that provided by the United States’ federal government. C. Changes Proposed by Witnesses Invited to Address Topics Other Than “Increasing the Competitiveness of Canadian Businesses Through Research, Development, Innovation and Commercialization”The Committee’s witnesses were invited to speak about a particular topic. When they appeared, they often made comments about one of the other five topics selected by the Committee, as indicated below. 1. “Balancing the Federal Budget to Ensure Fiscal Sustainability and Economic Growth” WitnessesThe Canadian Council of Chief Executives proposed the creation of a direct support program for R&D to encourage innovation and improve productivity in the private sector. 2. “Supporting Families and Helping Vulnerable Canadians by Focusing on Health, Education and Training” WitnessesRegarding investments in research capacity, the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada requested long-term and sustained funding for the federal granting councils, as well as predictable and multi-year funding for research infrastructure through the Canada Foundation for Innovation. Similarly, the Canadian Federation of Students’ brief proposed that, in order to promote long-term innovation and skills development, the government redirect granting council funding that is targeted to short-term private-sector priorities to research that has been determined, by a peer review process, to be of academic merit. As well, in order to promote graduate research and to increase graduate study enrolment and completion rates, the brief suggested that the number of Canada Graduate Scholarships increase at the same rate as the average rate of growth in federal funding for research, and distributed among the granting councils according to enrolment. 3. “Ensuring Prosperous and Secure Communities, Including Through Support for Infrastructure” WitnessesWith a view to increasing the competitiveness of the transit sector, the Canadian Urban Transit Association proposed the establishment of a partnership between the government and the Canadian Urban Transit Research Innovation Consortium that would make investments in R&D in that sector. The Mowat Centre encouraged the federal government to collaborate with provincial governments in the development of a strategy for the manufacturing sector; among other things, that strategy would focus on opportunities in advanced manufacturing. The Canadian Electricity Association proposed renewal of the Automotive Partnership Canada, which provides funding for R&D activities in the automotive sector, including electric vehicles. 4. “Improving Canada’s Taxation and Regulatory Regimes” WitnessesThe Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada proposed the creation of a “patent box” tax incentive that would reward innovative companies with a lower corporate tax rate on profits earned through the commercialization of patents in Canada. 5. “Maximizing the Number and Types of Jobs for Canadians” WitnessesThe Canadian Chamber of Commerce proposed that the Scientific Research and Experimental Development investment tax credit be replaced with a system that targets innovation more directly through lower tax rates for business revenue derived from patents or innovations developed in Canada; in particular, the systems in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Ireland and Switzerland were mentioned. To limit the potential abuse of the tax system, such as through businesses periodically modifying an existing patent to take advantage of the tax credit on a continual basis, it suggested that a limit be placed on the amount of revenue that could be claimed against the tax credit and that strict guidelines regarding eligibility for the tax credit be established. |