INDU Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

CHAPTER 2:

CANADIAN MANUFACTURING SECTOR

TRENDS AND CHALLENGES

CANADIAN MANUFACTURING SECTOR TRENDS

The Canadian manufacturing sector, along with the manufacturing sectors of other OECD countries, was not at the centre of the world's most recent economic thrust. World economic growth was centered principally on primary commodities, most notably energy and base metals. Hence, any expansion of manufacturing output was at best a by-product of this commodities boom, as incomes and spending multipliers of these resource-based industries took hold. For commodity export countries, other economic effects weighed in and had a more telling impact on their manufacturing sectors. For Canada, rising primary commodity prices were accompanied by an appreciation of the Canadian dollar, which immediately drove down the competitiveness of Canadian manufacturers relative to their foreign rivals. Indeed, Canadian manufacturing shipments plummeted and remained depressed for approximately three years during the ascent of the Canadian dollar (see Figure 11). But after considerable industry restructuring, the Canadian manufacturing sector has regained some of its lost competitiveness, and manufacturing shipments in Canada have rebounded. The annual growth rates of manufacturing shipments were 8.5% and 3.0% in 2004 and 2005, respectively, and this performance is considered healthy and vibrant by most standards. Manufacturing shipments stood at $611.5 billion in 2005.

With the retrenchment of shipments beginning in 2001, labour productivity and corporate profitability in the manufacturing sector declined and turned negative for two years. Together, these factors conspired to bring about many plant closures and a fresh round of employee layoffs. Since its peak of 2.32 million in the fourth quarter of 2002, employment in the manufacturing sector has been in decline (see Figure 12). The total number of employees who were laid off by the manufacturing sector between late 2002 and August 2006 was approximately 233,900, and manufacturing employment has hovered about 2.1 million since then. Given a Canadian dollar that appears to have peaked at US90.1¢ only in May 2006, it appears that employment in the manufacturing sector may have bottomed out.

Source: Russell Kowaluk, "Manufacturing: The Year in Review," Statistics Canada, Catalogue 11-621-MIE, http://www.statcan.ca/english/research/11-621-MIE/11-621-MIE2006045.pdf.

Source: Statistics Canada and the Bank of Canada

Recent developments in manufacturing employment are not, of course, solely the result of the appreciation of the Canadian dollar. Other forces are at work. Structural change away from manufacturing and towards services within most mature OECD developed countries, and the Canada‑U.S. Free Trade Agreement (FTA) have and continue to play a role.

The FTA has had an impact on the timing of employee layoffs implemented by Canadian manufacturers. This impact is observable from the data on manufacturing employment and the value of the Canadian dollar (see Figure 12). Developments in manufacturing employment clearly lag those of the Canadian dollar. When the Canadian dollar appreciates in value, employment in manufacturing falls; when the Canadian dollar depreciates in value, employment in manufacturing rises. The only question remaining is the exact timing of the lag.

There were two periods of sustained appreciation of the Canadian dollar and two periods of sustained manufacturing employment decline that followed. The first period predates the FTA and the other occurs with the FTA firmly in place and fully implemented.[10] In the pre-FTA environment, the lag between the beginning of the Canadian dollar's appreciation and the beginning of manufacturing employment losses was three years. When the dollar had finished appreciating five and three-quarter years later, the 23.7% appreciation coincided with 372,300 job losses, representing a 17.4% decline in employment, four and a half years later.[11] In the FTA environment, the lag between the beginning of the Canadian dollar's appreciation and the beginning of manufacturing employment losses was nine months. The 42.2% appreciation of the dollar in just four and a quarter years was followed by the loss of 208,900 jobs, representing a 9.2% decline in employment in four years.

These data suggest that the forging of the FTA and the removal of sizeable tariffs imposed on manufactured goods, particularly in the case of Canada, increased the intensity of competition between Canadian and U.S. manufacturers. The Canada-U.S. dollar exchange rate now provides a sharpened competitive edge and, as a result, Canadian manufacturers are forced to respond more quickly to exchange rate movements (i.e., more immediate layoffs when the Canadian dollar rises in value).

Manufacturing employment as a share of total employment for all industries within Canada fell to 13.7% in 2005,[12] the lowest level since 1976. Most OECD countries have experienced similar declines in the share of manufacturing in total employment (see Figure 13). Research by the OECD suggests that the relative decline in the share of manufacturing in production and value-added results primarily from relatively slow growth in demand for manufacturing products, as demand for services is growing more rapidly. The relative and absolute decline in manufacturing employment is primarily due to strong productivity growth, but it is also affected by the growth of manufacturing capacity in non-OECD countries. However, according to the OECD, the loss of manufacturing employment in OECD countries cannot simply be characterized as a transfer of manufacturing production to non-OECD countries, since manufacturing employment in non-OECD countries has not grown significantly.

Europe = Austria, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Spain and Sweden.

Source: Industry Canada submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology, meeting of 13 June 2006 and OECD STAN Indicators database.

Finally, labour productivity growth has returned in robust fashion to the Canadian manufacturing sector. After three years of poor growth — averaging 0.1% per year — and even decline, labour productivity grew by 3.5% and 5.7% in 2004 and 2005, respectively (see Figure 14). Indeed, because of considerable industrial restructuring that included plant closures and employee layoffs, the manufacturing sector outperformed the larger business sector in the past two years. Labour productivity growth in the Canadian manufacturing sector has been three times that of the Canada's business sector since 2004. The slightly smaller manufacturing sector is thus much stronger and more resilient than before.

Source: Russell Kowaluk, "Manufacturing: The Year in Review," Statistics Canada, Catalogue 11-621-MIE, http://www.statcan.ca/english/research/11-621-MIE/11-621-MIE2006045.pdf.

MAJOR CHALLENGES FACING THE CANADIAN MANUFACTURING SECTOR

1. Rapid Appreciation in the Value of the Canadian Dollar

Relative to the services sector, the manufacturing sector has a higher exposure to international trade. Exports from the manufacturing sector are often priced in U.S. dollars, and as the Canadian dollar has risen, margins have shrunk as the prices of these exports dropped in Canadian dollar terms. Because of competitiveness concerns or the fact that prices for exports may be fixed far in advance in U.S. dollars, many firms have been unable to raise their U.S. dollar prices.

The Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters (CME) presented two surveys to the Committee that it undertook under its 20/20 manufacturing initiative, one identifying manufacturers strategic challenges and the second identifying constraints on export growth. In both cases, currency exchange rates were listed as the most challenging factor. In the first survey, the high dollar and the resultant lower prices were listed, while the second survey listed managing exchange rates, suggesting that a fluctuating currency (even when the fluctuation is not large) poses a challenge (see Figure 15).

Source: Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology, meeting of 16 May 2006.

2. Increasing and Unpredictable Energy Costs

The manufacturing sector has also been adversely affected by increasing input costs. Energy-intensive manufacturing industries such as pulp and paper, chemical, petroleum refining and primary metal industries make up approximately 29% of Canada's manufacturing GDP,[13] and these industries have been hit particularly hard by increasing energy (electricity, fuel oil and natural gas) costs. Between the first quarter of 2000 and the fourth quarter of 2005, manufacturers saw their energy costs increase by 94.3% (see Figure 16). Additionally, while electricity deregulation, which has occurred in some jurisdictions, has led to more efficient production and relatively lower prices, some manufacturers in these jurisdictions have experienced insecure supplies of electricity (e.g., brownouts and power outages).

Member surveys of the Canadian Federation of Independent Business (CFIB) agree with those of the CME. Energy prices are identified as the leading business factor adversely affecting manufacturing firms.

Intertwined with high energy prices is the unpredictability of energy prices. For some energy-intensive manufacturers, current and predicted future energy prices have a large impact on strategic decision-making. Energy price fluctuations exacerbate both business planning and decision-making.

Source: Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology, meeting of 16 May 2006.

3. Competition from Emerging Economies

The Canadian manufacturing sector has been affected by global competition, particularly from China. China is a large and rapidly growing market for raw materials, industrial goods, capital equipment, and consumer products. The country has become a leading manufacturer, not only of textiles and consumer products, but of electronic equipment, software, and other technologies as well. China's labour costs are, on average, about 1/40th of those in Canada, and they provide China with a comparative advantage in the manufacture of labour-intensive products. China has also become an integral part of manufacturers' global supply chains.[14] Canada is also facing low cost and high value competition from other emerging economies, such as India.

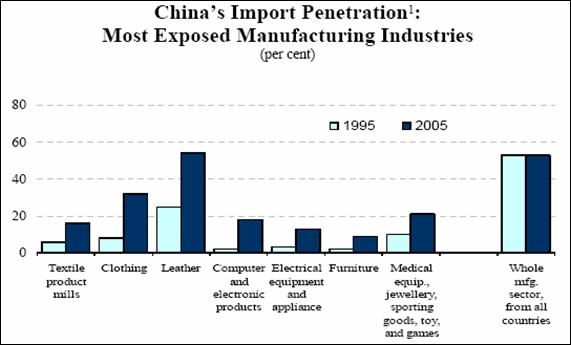

Although import penetration into Canada from all countries has been relatively stable over the past decade, there has been a change in the relative positions of the countries of origin of imports. In particular, import penetration from China has risen. Some manufacturing industries with a high trade exposure have experienced lower profit margins, prices or sales volumes in their domestic markets because of increased competition from imports, particularly from China (see Figure 17).

Note: Import penetration is measured as the value of imports from China divided by the value of the domestic market (shipments plus imports minus exports)

Source: Industry Canada submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology, meeting of 13 June 2006.

The emergence of China in the Canadian market is a challenge that many Canadian manufacturers, particularly those whose products have a medium to high labour content, will have to overcome. However, the presence in Canada of capital-intensive products from China at prices lower than in their home market (possibly being "dumped" or subsidized) because the Chinese government has chosen to support an industry as a strategic export good for the country's rapid industrialization poses an extraordinary challenge. Here, steel and steel products come immediately to mind.

4. Availability of Skilled Labour

Despite current job shedding, the manufacturing sector, like all other sectors of the Canadian economy, has to address the shortage (actual or potential, depending upon the industry or region of the country in question) of skilled labour. Over the past decade, three main factors have shaped Canada's workforce: (1) an increasing demand for skills in the face of advanced technologies and the "knowledge based economy"; (2) a working-age population that is increasingly made up of older people; and (3) a growing reliance on immigration as a source of skilled labour.[15] Added to this mix of long-term trends is a rather recent structural development that is forcing a reallocation of labour both from one sector of the economy to another and from one region of the country to another: the high value of the Canadian dollar.

Source: Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters submission to the House of Commons Standing

Committee on Industry, Science and Technology, meeting of 16 May 2006.

According to a survey conducted by the CME in 2003,[16] more than 40% of manufacturers say that skills shortages are seriously constraining their ability to improve business performance and grow. About 17% of those surveyed indicated that skills shortages pose a major constraint on their ability to develop and commercialize new products. Finally, slightly more than 25% reported that a lack of skilled and experienced personnel is a challenge that will fundamentally change the nature of their business over the next 5 to 10 years. The survey also identifies specific labour skills shortages by occupation that the manufacturing sector is facing (see Figure 18).

In a survey undertaken in January 2005 by the Canadian Federation of Independent Business (CFIB), members listed the shortage of qualified labour third among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) business priorities. The labour skills shortage is therefore an important challenge for the manufacturing sector.

5. Regulatory Environment

Many witnesses indicated that government regulations represent a burden to their industry and to all sectors of the economy. The major business associations (e.g., Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters, Canadian Chamber of Commerce, Canadian Council of Chief Executives, Canadian Federation of Independent Business, Conference Board of Canada) suggested that streamlining regulations and reducing paper burden is a cost-effective way to increase productivity and to help businesses of all sizes and from all sectors.

Source: Canadian Federation of Independent Business submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology, meeting of 16 May 2006.

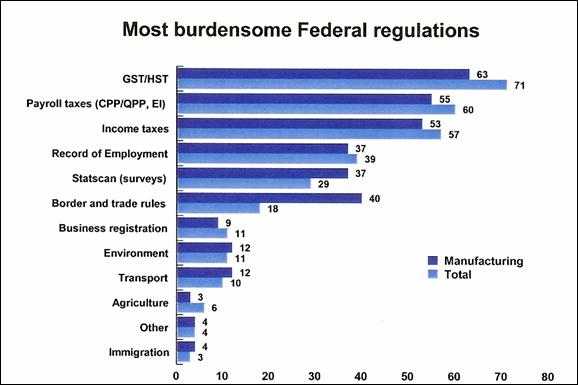

In the CFIB survey mentioned above, members listed government regulation second among the business priorities of SMEs. In the same survey, CFIB members (manufacturers and others) listed the most burdensome types of federal regulations (see Figure 19). The top three on the list were compliance with tax regulations (i.e., the GST, payroll taxes and income taxes).

[10] In the first period, the Canadian dollar's appreciation begins before the FTA came into effect, whereas manufacturing employment losses (from start to finish) coincide with the FTA.

[11] Daniel Trefler calculates that "the Canadian tariff cuts explain about half of the employment losses over the [1988-1995] period" (see Daniel Trefler, "The Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement: An Assessment for Canadian Manufacturing," 1998. See also Daniel Trefler and Noel Gaston, "The Labour Market Consequences of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement," Canadian Journal of Economics, XXX(1), February 1997, pages 18-41 http://www.nber.org/ftp/trefler/FTA/readme.html).

[12] Russell Kowaluk, Manufacturing: The Year 2005 in Review, Statistics Canada, June 2006, http://www.statcan.ca/english/research/11-621-MIE/11-621-MIE2006045.pdf.

[13] Data presented by Mr. Howard E. Brown, Assistant Deputy Minister, Department of Natural Resources to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology, meeting of 13 June 2006.

[14] Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters, Manufacturing Challenges in Canada,

http://www.cme-mec.ca/mfg2020/Challengespdf.pdf.

[15] Statistics Canada, 2001 Census analysis series:

The changing profile of Canada's labour force, 2003,

http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census01/Products/Analytic/companion/paid/pdf/96F0030XIE2001009.pdf.

[16] Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters 2003 Membership

Survey cited in Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters, Manufacturing Challenges in Canada,

http://www.cme-mec.ca/mfg2020/Challengespdf.pdf.