HUMA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

CHAPTER 3 — INCREASING LABOUR FORCE

PARTICIPATION AND

STRENGTHENING WORK INCENTIVES

As shown in Chart 3.1, the proportion of Canadian workers within 10 years of the median retirement age has almost doubled in the last 30 years. In 1976 there were about 1.14 million workers so defined. By 2006, their numbers had risen to approximately 3.8 million. This trend clearly illustrates the momentum behind labour force aging and the potential exodus of workers from the Canadian labour market in the next decade and beyond. There has, however, been a noteworthy development of late, as displayed by the cessation of the downward trend in the average age of retirement.

As evidenced by the data illustrated in Chart 3.1, the average age of retirement declined from 64.9 years in 1976 to 60.9 years in 1998 and has since risen to 61.5 years in 2006. Underlying this trend is an increase in labour force participation among older workers (defined here as individuals 55 years of age and over). Between 1996 and 2006, the labour force participation rate among individuals in this age group increased by 8.5 percentage points, almost three and one-half times the increase in the participation rate for all individuals 15 years of age and over. Also of note, the participation rate of individuals between 60 and 64 years of age and 65 years of age and over increased by 12 and 2.4 percentage points respectively during the same period.

A. Strengthening Incentives to Work

Many witnesses indicated that, in order to make work more attractive to older workers, employers need to recognize the important role older workers can play in alleviating skills shortages and, in doing so, to implement more flexible employment policies such as gradual retirement and reduced hours of work. The importance of flexible work arrangements is evident from the results of Statistics Canada’s 2002 General Social Survey, which indicated that more than one-quarter of retirees might have changed their retirement decisions if they had been able to alter their work schedules.[160] Employers may also need to modify their workplaces to accommodate an older workforce.

There are issues around employer awareness. For example, many older workers, myself included, cannot work in low-light environments. If an employer wants me to bring my skills into his place, he has to give me a chair that supports my back and light levels so I can actually perform the work. We don't have enough awareness yet, and the government can provide leadership to say, look, we have this untapped resource of older workers, and a little bit of investment — not a huge investment — by the employer will actually get you the people you need. It will also help with knowledge transfer, so younger people can have the information they need to retain the corporate vision, the institutional memory.[161]

Ms. Elly Danica, Older Worker Transitions

Acadia Centre for Small Business and Entrepreneurship

According to a 2005 survey of corporate executives by the Conference Board of Canada, few Canadian employers are developing strategies to deal with an aging workforce, even though most recognize that their organizations will encounter aging-related labour problems within the next five years.[162] This survey revealed that “almost 80 per cent of the respondents indicated that their organizations will face problems related to an aging workforce within the next five years, with 23% admitting they are already experiencing difficulties.”[163] The absence of meaningful action to deal with this inevitable and imminent situation is worrisome.

Many witnesses expressed the view that the federal government should initiate measures to extend, on a voluntary basis, labour force participation among older workers. Given this group’s skills and experience, prolonging older workers’ attachment to work could help mitigate future skill imbalances across the country. Witnesses’ suggestions to facilitate this included eliminating mandatory retirement, phasing in retirement, enhancing financial incentives to work and providing more adjustment assistance to older workers.

While most jurisdictions in Canada have abolished mandatory retirement, some continue to treat forced retirement at age 65 as a non-discriminatory practice. British Columbia, Saskatchewan and, Newfoundland and Labrador still maintain an age cap of 65 in their human rights codes to accommodate mandatory retirement. Ontario recently abolished this practice. Only Quebec and Manitoba have banned contractual mandatory retirement (forced retirement according to the terms of a pension plan or a collective agreement).[164] Although mandatory retirement does not exist in the federal public service, this is not the case in other workplaces that fall under federal jurisdiction. In this regard, the Committee was reminded that section 15(1)(c) of the Canadian Human Rights Act states that it is not a discriminatory practice to terminate an individual’s employment because he or she has reached the normal age of retirement.

[W]e certainly are totally against mandatory retirement. We think it has to be choice, and what we're missing now is choice when there is mandatory retirement. We get calls almost every day. At a conference we had last week, we met someone who had worked for an airline. She said when she was 64 she was okay, and then when she turned 65 suddenly they were saying she wasn't able to do the job, but she wanted to continue working. Most people will retire. We're not even saying that most people will continue to work if they have a choice, but there should be incentives and benefits for those who do choose to work or to go back to work. We really don't promote making anyone retire at any age.

Ms. Judy Cutler

Canada's Association for the Fifty-Plus[165]

Members of the standing committee know that mandatory retirement at age 65 is still the rule in this country. With the exception of Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba, governments permit mandatory retirement. Indeed, the Canadian Human Rights Act includes a special provision that allows employers to dismiss workers on account of age. Compulsory dismissal at age 65 was never a justified practice. The Charter of Rights and Freedoms forbids discrimination on the basis of age, but the persistence of ageism among powerful constituencies in Canada, including governments, the courts, unions, and employers, meant that efforts over the past twenty years to end mandatory retirement were unsuccessful until the historic decision of the Ontario government.[166]

Prof. David MacGregor

King's University College at the University of Western Ontario

While several witnesses called for the abolition of mandatory retirement in Canada, the Committee is mindful of the jurisdictional constraint associated with this proposal. In addition, the Committee stresses that its support for the abolition of mandatory retirement should not be construed as requiring older workers to work beyond the age of 65. We only intend to accommodate those who wish to do so voluntarily.

If you start depending on an aging workforce, you're going to run into health problems, and then you're no further ahead. It's got to be the younger workforce, but the training isn't there, and it should be, because that's who you're going to look to for employment. I've been working since I was 16, and it will be 50 years or more that I've worked. I worked hard as a child and I don't want to work beyond 65.[167]

Ms. Trudi Gunia

As an Individual

Recommendation 3.1

The Committee recommends that the Minister of Labour encourage provincial and territorial labour ministers to establish a working group to examine barriers to continued employment among workers once they reach the age of 65, especially with regard to mandatory retirement provisions that continue to operate in some parts of the country.

Recommendation 3.2

The Committee recommends that the federal government examine section 15 of the Canadian Human Rights Act with a view to defining as a discriminatory practice the termination of an individual’s employment because he or she has reached the normal age of retirement for employees working in similar positions.

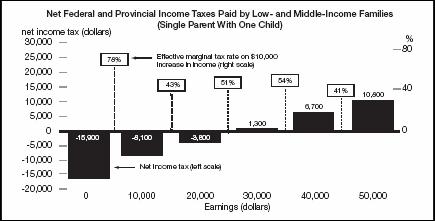

Mandatory retirement and the absence of flexible work arrangements are not the only factors constraining labour supply decisions among older workers, many of whom also face significant financial disincentives to work. Individuals who receive the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS) or Allowance have their benefits reduced if they report an increase in income, such as earnings from employment. Moreover, if these individuals pay income tax on these earnings the combined effective tax rate on income from employment can be substantial.

The clawback on GIS/Allowance payments depends on an individual’s marital status and on whether a spouse or common-law partner is receiving Old Age Security (OAS) or allowance payments. In the case of a single, widowed or divorced pensioner receiving the GIS, for example, monthly GIS benefits are reduced by one dollar for every $23.99 increase in yearly income (excluding OAS) above $24 (i.e., the reduction point). In other words, if this pensioner also pays income tax on earnings, he or she faces an effective tax rate exceeding 50%.[168] Even if there is no income tax paid on earnings, the GIS clawback renders paid employment an unattractive proposition.

Budget 2008 proposes to increase the earnings exemption associated with the GIS to $3,500 per year.

The Canada Pension Plan (CPP) also has drawbacks for those who would like to remain attached to the labour market. Although a partial CPP pension may encourage early retirement, it should be noted that this pension benefit is payable only if an applicant ceases to be engaged in paid employment or self-employment or if the applicant’s estimated earnings for the year in which the retirement pension would begin to be paid is less than 25% of maximum pensionable earnings.[169] This eligibility condition is potentially problematic for many older workers who are forced to experience a period of unemployment in order to become eligible for a partial pension. Once unemployed, some of these workers undoubtedly face serious challenges finding another job, an issue that is afforded more discussion below.[170]

Another potential disincentive to work associated with a partial CPP pension relates to a finding in a recent study by the CPP’s Chief Actuary. According to this study, the legislated actuarial adjustment is too generous for those who elect to receive their pension before the age of 65 and not generous enough for those who elect to receive their pension after the age of 65. In other words, the plan is subsidizing those who opt for early retirement.[171]

[W]e would suggest a review of the pension and income tax policies that currently create a disincentive for mature workers to consider part-time employment, because we do see this as being a primary source of an alternative labour market for the grocery retail sector, especially considering that demographics are projecting such a shrinkage in the youth workforce, which is currently our primary source.[172]

Ms. Cheryl Paradowski

Canadian Food Industry Council

[W]e have been advocating and in fact in the former government the Minister of State responsible for seniors advocated a band above the low-income cut-off line that seniors could receive through working, without endangering the guaranteed income supplement. I believe the band that had been recommended was around $2,000 or $3,000, and we said the same. It's not to force people to work, but if they have to work to augment their income, they should not lose the benefits they have […][173]

Mr. William Gleberzon

Canada's Association for the Fifty-Plus

Federal rules for private pension and Canadian pension plan encourage early retirement and discourage part time work past the age of 65. Pension regulations, especially those governing defined benefit plans, need to be modernized so that companies can set up phased retirement programs where mature workers can work part-time and draw on their pension to supplement their salary.[174]

Retail Council of Canada

Recommendation 3.3

The Committee recommends that in their next triennial review of the Canada Pension Plan the Ministers of Finance consider possible changes to the Plan to better accommodate concurrent work and partial pension payments, and examine the need for actuarial adjustments to Canada Pension Plan payments with a view to ensuring that the impact of this program on seniors’ decisions to remain in the workplace is, at the very least, neutral.

Recommendation 3.4

The Committee recommends that the federal government monitor and assess the impact of the proposal in Budget 2008 to increase the Guaranteed Income Supplement earnings exemption to $3,500.

In concert with the upward trend in labour force participation among older workers, the level of employment (and the employment rate) among workers 55 years of age and over has increased appreciably in the last decade. Between 1996 and 2006, job creation among older workers increased by 81%, more than three and one-half times the growth in employment for all ages during the same period. Almost four-fifths of this increase was attributed to growth in full-time jobs. It is also noteworthy that employment growth among workers 65 years of age and over was also quite robust during this period, increasing by 62% between 1996 and 2006.

Despite the relatively robust growth in job creation among older workers in the past ten years, this group’s labour market performance between 1996 and 2006, as measured by the unemployment rate, was less impressive. During this period, the unemployment rate among older workers declined from 7.3% in 1996 to 5.1% in 2006, only two-thirds of the decline in the unemployment rate for the labour market as a whole. Moreover, the unemployment rate among workers 65 years of age and over increased from 3.8% in 1996 to 4.4% in 2006.

While older workers tend to experience unemployment less frequently than their younger counterparts, when unemployment does occur older workers typically experience longer spells of joblessness. This observation is depicted in Chart 3.2, which shows the incidence of long-term unemployment (i.e., unemployment for 27 weeks or more) among older workers compared with the labour force as a whole. According to these data, the overall incidence of long-term unemployment declined between 1996 and 2006. This result is not surprising given that the national unemployment rate dropped by 3.3 percentage points during this period. Nevertheless, it is obvious from the data depicted in Chart 3.2 that proportionately more older workers experience longer periods of unemployment than their younger counterparts. Although this effect is not illustrated in this chart, in 2006, 14.7% of workers 55 years of age and over experienced unemployment for 52 weeks or more, almost 1.8 times higher than the proportion of all unemployed workers who were unemployed for 52 weeks or more.

Although there are many reasons why older workers tend to experience longer spells of unemployment than younger workers, inadequate skills and a lack of workplace training opportunities are undoubtedly key contributors. As discussed in Chapter 2 of our report, older workers have relatively fewer opportunities to participate in employer-sponsored training. In addition to a relatively shorter payback period for employers to recoup the costs of training older workers, we suspect that many older workers are unable to participate in training because a high proportion of them lack basic literacy and numeracy skills. According to the 2003 Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey, more than one-half of Canadians aged 46 to 65 had low literacy skills.[175]

As previously mentioned, the federal government funds a number of labour market adjustment programs, the lion’s share of which is delivered under EI’s Employment Benefits and Support Measures (EBSMs). According to data contained in the Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report 2006 (the most recent available), workers 55 years of age and over were somewhat under-represented in terms of their participation in EBSMs in 2005-2006. In 2005, individuals 55 years of age and over represented roughly 14% of the labour force and 11.3% of unemployed people. Nationally, only 6.6% of similarly aged individuals participated in EBSMs in 2005-2006; this proportion varied considerably across the country from highs of 7.7% and 7.4% in British Columbia and Ontario respectively, to lows of 2.3% in Nunavut and 3.7% in the Northwest Territories.[176] Members of the Committee believe that older workers’ participation in federal labour market programs must increase to reflect this group’s growing share of the labour force.

In June 1999, the federal government introduced the Older Workers Pilot Projects Initiative, a program designed to test various approaches to helping unemployed older workers regain employment or maintain employment if job loss becomes a risk. Following a recent evaluation of this initiative, the federal government announced, on October 17, 2006, that it would introduce a federal-provincial cost-shared (70%-30%) program called the Targeted Initiative for Older Workers (TIOW). The federal government’s share of funding under this program is expected to be $70 million over two years. As of March 2008, nine jurisdictions — British Columbia, New Brunswick, Northwest Territories, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Quebec, Saskatchewan and the Yukon — have signed agreements under this initiative.

The TIOW is targeted at older workers 55 to 64 years of age who have lost their jobs, are legally entitled to work in Canada, lack the skills needed to secure new employment and reside in communities that are experiencing high unemployment or that rely heavily on a single employer or industry affected by downsizing or a closure. Although witnesses were generally supportive of the TIOW, some raised concerns about limiting program participation to those aged 55 to 64. If the federal and provincial/territorial governments are genuinely interested in providing adjustment support to an aging workforce, consideration should be given to broadening the age-eligibility criterion under the TIOW and other labour market interventions. Furthermore, it is highly unlikely that the labour market adjustment problems currently facing older workers are concentrated in high unemployment communities or single-industry (employer) communities. It is for this reason that we recommended, in Chapter 2, the use of EI contribution rebates to help facilitate labour market adjustments among older workers (and others) across the country.

On January 23, 2007, the Minister of Human Resources and Social Development announced the appointment of an expert panel to study labour market conditions affecting older workers and potential measures to help this segment of the labour force. Members of the Committee note that this expert panel would be an appropriate vehicle for examining age- and community-eligibility criteria under the TIOW. This panel could also review the efficacy of supporting: (1) an internship initiative to assist older workers who want to remain in the workplace, but who lack job-specific experience and skills to fill job vacancies; and (2) a mentorship initiative to allow older workers to pass on their expertise to younger workers before leaving the labour force.

[S]upport mentorship programs that are not age-restricted to facilitate career development in succession. It is in this area that we're starting to address the older part of the workforce. The federal government has been very supportive with youth internships, as well as addressing the issue of school dropout, etc., and that bridge between school and work. We're seeing that there is also a very big issue that's being addressed by older workers; if we could extend those youth internship programs to include other ages, you would be able to address succession issues and career transfer issues, transition issues, for older workers as well.[177]

Ms. Susan Annis

Cultural Human Resources Council

Recommendation 3.5

The Committee recommends that the federal government examine the efficacy of broadening the age and community eligibility criteria under the Targeted Initiative for Older Workers. In addition, consideration should be given to broadening the scope of this or some other program to support internship and mentorship opportunities for older workers. In the event that the Targeted Initiative for Older Workers program is broadened, funding could come from the newly announced $500 million investment in new labour market programming, given that one of the stated objectives of this spending is to increase the labour force participation of under-represented groups in the Canadian labour market.

The Aboriginal working-age population (i.e., 15 years of age and over) represents a growing segment of the Canadian labour force. According to the 2001 Census, 3.3% of Canada’s total population was of Aboriginal identity (almost 1 million people).[178] The Aboriginal population as a percentage of the total population is largest in Nunavut (85%), the Northwest Territories (51%), the Yukon (23%) and Western Canada, particularly in Manitoba (13.6%) and Saskatchewan (13.5%). It is a young population, with a median age in 2001 that was 13 years younger than that of the non-Aboriginal population (24.7 years as opposed to 37.7 years). By 2020, it is estimated that over 400,000 young Aboriginal people will be of working age.[179]

Canada needs a well-educated and skilled Aboriginal workforce. Research has shown that over the last decade Aboriginal people have made significant progress in terms of their educational and employment outcomes. However, their levels of education and employment are still well below those of the non-Aboriginal population.

Canada will face a skilled labour shortage as many Canadian baby boomers start retiring and the economy remains strong. At the same time, Aboriginal people in Canada are the nation's youngest and fastest growing segment of the population. We must find a way to change the high percentage of unemployment for Aboriginal people, utilizing both on- and non-reserve approaches. The Aboriginal population is the largest untapped human resource in Canada, and we believe we can solve Canada's labour shortage.[180]

Ms. Sherry Lewis

Native Women’s Association of Canada

In 2001, 38.7% of Aboriginal people aged 25 to 64 had less than a high school graduation certificate, as opposed to 22.7% of the total working-age population. In terms of trades-related training, Aboriginal people achieved better rates of completion than the non-Aboriginal population (16% as opposed to 13%). However, those results are an exception, in that a smaller proportion of Aboriginal people obtained a college or university degree than non-Aboriginal individuals. Fifteen percent of Aboriginal people had a college certificate or diploma, and 8% reported having a university degree. Among the non-Aboriginal population, 18% had a college certificate and 22.6% had completed a university education.[181]

1. Barriers to Post-Secondary Education

Aboriginal learners must overcome a number of barriers to post-secondary education. According to a study published by the Canada Millennium Scholarship Foundation, these barriers include: inadequate financial resources; poor academic preparation; a lack of self-confidence and motivation; an absence of role models who have post-secondary education experience; a lack of understanding of Aboriginal culture on campus; and racism. Of all the barriers constraining Aboriginal learners from attending post-secondary education, insufficient financial resources and poor academic preparation were cited most often by First Nations people living on reserves. Financial barriers do not stem only from low incomes. The Foundation’s study also revealed that Aboriginal students at the post-secondary level are, on average, older than other students and are more likely to be married and/or to have children. These student characteristics tend to augment household expenses and the need for child care.[182] Hence, effective financial assistance programs for Aboriginal students must account for the financial needs of an older student population and single parents.[183]

2. Federal Programs Supporting Aboriginal Education

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) spends about $1.6 billion on elementary, secondary, and post-secondary education for First Nations and Inuit students. The Department supports the provision of elementary and secondary education programs and services for First Nations students and offers financial support for post-secondary education to Inuit and First Nations (Status Indians) residing on or off reserves.[184]

The Post-Secondary Student Support Program (PSSSP) and the University College Entrance Preparation Program (UCEP) provide financial assistance to help cover the costs of tuition, books, travel and living expenses. The Indian Studies Support Program (ISSP) also provides support “to post-secondary institutions for the development and delivery of special programs for Indians.”[185] The three support programs are administered and delivered almost exclusively by First Nations Bands, whose Councils define their own selection criteria and policies.[186] INAC has a budget of about $300 million for post-secondary education programs. Most of this funding is earmarked for the Post-Secondary Student Support Program.[187]

According to a recent evaluation of INAC’s Post-Secondary Student Support Program, this program is relevant and effective. Most program participants indicated that they would not have obtained a post-secondary education without the support of this program. However, resources are limited and the guidelines for living allowances under the PSSSP are outdated. The demand for financial assistance exceeds the resources available. Organizations administering PSSSP funds indicated that about 22% of applicants were put on a waiting list. On the basis of all the information available, evaluators concluded that each year about 3,575 applicants are unable to access financial assistance under the PSSSP because of a lack of funding.[188] According to the Assembly of First Nations, about 9,500 First Nations students who are eligible and looking to attend post-secondary education are on waiting lists.

The employment rate for Aboriginal people in Canada is well below the rate for non-Aboriginal people, and there is a significant disparity between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students enrolled in post-secondary education. Current federal funding programs are not accessible to all Aboriginal students who should have the option of accessing them. Additionally, federal funding has reached its maximum, which does not account for rising costs of tuition and the increase in Aboriginal enrolment. Developing a more highly skilled and educated Aboriginal population is vital for the future economic and social development of Canada.[189]

Sustained Poverty Reduction Initiative

The House of Commons Standing Committee on Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development recently completed a study of Aboriginal post-secondary education and came to similar conclusions. While recognizing the progress made by Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal stakeholders in developing and delivering post-secondary programming to Aboriginal learners, the report states that “it appears there are uncounted numbers of aspiring Aboriginal learners who are unable to gain access to the funding they need to enroll in post-secondary programs.”[190] Although the report deals mainly with funding provided under INAC’s post-secondary education program, the lack of funding to meet the needs of Métis and non-registered First Nations learners is also recognized as a problem that requires immediate attention.

To support and encourage the attainment of higher levels of education by all Aboriginal learners, including Aboriginal populations that are not eligible to receive support under INAC’s programs, the federal government announced in 2003 a one-time $12 million endowment to establish a new post-secondary scholarship. The scholarship is offered to First Nations (status and non-status), Métis and Inuit learners enrolled full-time or part-time in programs of two or more academic years in duration. The scholarship fund is administered and delivered by the National Aboriginal Achievement Foundation (NAAF).[191] In Budget 2005, the federal government committed an additional $10 million in 2005-2006 to the NAAF to support the post-secondary education aspirations of Aboriginal students.

B. Aboriginal Labour Market Participation

Aboriginal people are also under-represented in the labour market. In 2001, the employment rate (i.e., employment expressed as a percentage of the population 15 years of age and over) for the Aboriginal population was 49.7%, well below the rate of 61.8% for non-Aboriginal people. These differences vary according to residential location and educational attainment. Aboriginal people living in urban metropolitan areas are more likely to be employed than those living elsewhere, particularly those living on reserves. Reserves are often located in remote locations and generally offer few employment opportunities. Approximately 53% of First Nations individuals live on reserves. In 2001, the employment rate was 37.7% for people living on reserves, compared with 54.2% for those who were living in non-reserve areas. Not surprisingly, the employment rate also increases with higher levels of educational attainment. Slightly over 82% of Aboriginal people (25 to 64 years old) with a university degree were employed in 2001, compared with 43% of those with some high school education or less.[192]

In 2001, Aboriginal people aged 15 years and over were more likely to be unemployed (19.1%) than the non-Aboriginal population (7.1%) in 2001.[193] The Committee was told that the unemployment rate for those living on reserves was as high as 28%. There were also clear variations from one region of the country to another. Aboriginal unemployment rates in Manitoba and Saskatchewan were three to four times those of the non-Aboriginal population (18% and 22% respectively).[194] These high unemployment rates are unjustifiable, particularly in view of the fact that Canada is experiencing skills shortages in certain economic sectors and regions of the country.

The reasons underlying low labour force participation rates and the high unemployment rates among Aboriginal people are complex and not yet fully understood. However, it is clear that high school completion rates must be addressed, access to post-secondary education must be facilitated, and barriers to employment must be dealt with if we are to improve the socio-economic status of Aboriginal people.

Research has also shown that poor health, poverty, unsuitable living conditions (e.g., inadequate housing), racism and discrimination have a direct impact on the social, educational, and occupational achievements of Aboriginal people.[195] Income is a basic indicator of economic well-being. The 2001 Census shows that there is a significant income gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in Canada. In 2000, the median income of the Aboriginal population was $13,525, compared with $22,431 for the non-Aboriginal population. Aboriginal people who worked year-round, full time earned on average $33,416, whereas non-Aboriginal working Canadians had average earnings of $43, 486.[196]

To increase employment opportunities for Aboriginal people, we also need to consider mobility issues. Aboriginal individuals are much more mobile than other Canadians. In the year before the 2001 Census, 22% of Aboriginal people had moved compared with only 14% of non-Aboriginal people. Of those who moved, about one-third had moved to another community.[197] Young people moving off reserves to urban centres face particular challenges in their search for employment outside their own community. All of the activities associated with relocation must be accomplished without the support of the community and family they leave behind on reserves. They face language and cultural barriers. They must find suitable housing, look for a job and create a new social support network. The Committee was told that Aboriginal women face similar relocation challenges with the added difficulty that, as many are also single mothers, they need access to affordable, quality child care services that reflect Aboriginal culture and practices.

Our studies have found that child care and the costs of child care are difficult to access, and they are insufficient. This leads to single mothers having to carry the burden of child care on their own or having to receive government benefits and pass up the opportunities to train to re-enter the job market. Current initiatives do not have set-aside budgets for child care and limit the ability of aboriginal women to receive training by having such restrictive criteria.[198]

Ms. Sherry Lewis

Native Women’s Association of Canada

If you want to talk about employability, I would argue that the number one priority this committee should have is single women with children. If you get that young mother graduated through a program and into a well-paying job, you change her life and you change her child's life. Having been raised by a single mother, I can assure you that this mother will not allow her child not to succeed. She'll know the benefits and what it takes, and it will be a remarkable outcome for all of Canada. That's what I would say would be the ultimate success story.[199]

Mr. Peter Dinsdale

National Association of Friendship Centres

2. Enhancing Aboriginal Training and Labour Market Participation

During our hearings, some witnesses expressed concerns regarding the under-representation of Aboriginal people in the labour market and made suggestions to remove barriers to their full participation in education and employment. Most recognized that the Aboriginal population is part of the solution to existing and anticipated skills shortages. They also see the current labour market challenges as an opportunity to reduce the socio-economic woes that afflict Aboriginal people across Canada.

Aboriginal peoples and recent immigrants are experiencing very high rates of poverty and a very bad employment and employability situation, yet these are the very people we need to fill the gaps in our labour market resulting from Canada's aging population.[200]

Mrs. Sheila Regehr

National Council of Welfare

In our view, the acquisition of higher education, training and skills development provide the most promising approaches to increasing the labour market participation and living standards of Aboriginal people. The significance of education, apprenticeship training and the acquisition of basic skills in enhancing the participation of Aboriginal people in the economy was also highlighted in a recent report entitled Sharing Canada’s Prosperity — A Hand Up, Not a Handout.[201]

In light of the interest shown by Aboriginal people in trades-related occupations, some witnesses suggested that efforts should be made to facilitate Aboriginal participation in apprenticeship training and ensure that those who complete their training find jobs. A number of witnesses also indicated that there is a need for employers, Aboriginal workers and agencies that serve Aboriginal people to collaborate in the development of initiatives to provide the necessary supports to increase Aboriginal workers’ mobility and facilitate smoother transitions into the workplace. Some witnesses also thought that “mentorship programs” could be created so that Aboriginal people who have succeeded in breaking down the barriers to better employment could assist others to do the same.

In both Alberta and British Columbia, aboriginal people who have completed post-secondary education have higher participation rates than the non-aboriginal population with post-secondary education. Again, that is an indication that education matters.[202]

Ms. Maryanne Webber

Statistics Canada

As an example, there's little doubt that over the next five to seven years, Saskatchewan's tar sands will start to be developed just like Alberta's. The demand for skilled labour in this and other skill-starved sectors as well as other occupations could be filled by aboriginal people, but only if we start working on this now. We need a massive increase in financially supported academic and apprenticeship training opportunities for aboriginal people, and we need to start that now.[203]

Mr. Larry Hubich

Saskatchewan Federation of Labour

It's all about removal of barriers for aboriginal people to participate. It's all about significant investment by employers in making sure that aboriginal employees not only can be hired but can be retained and promoted. On the mining side, I think they've done an admirable job of training.[204]

Mr. Mark Hanley

Saskatchewan Labour Force Development Board

C. Federal Programs Promoting Employment for Aboriginal People

To increase the labour market participation of Aboriginal people and their standard of living, the federal government funds a number of education, training and employment services. Human Resources and Social Development Canada (HRSDC) oversees the Aboriginal Human Resources Development Strategy (AHRDS), an initiative launched in 1999 to facilitate labour market adjustment among Aboriginal people.[205] The Strategy was renewed in 2004 for a second five-year period with a total budget of $1.64 billion.[206] In 2006-2007, HRSDC spent $281.4 million under the AHRDS.[207] Funding under the Strategy is distributed via approximately 80 Human Resources Development Agreement holders, who design and deliver labour market, youth and child care[208] programs and services best suited to meet the local and regional needs of their communities. These programs and services help Aboriginal people prepare for, obtain and maintain employment and assist Aboriginal youth (15 to 30 years of age) in making a successful transition from school to work. According to HRSDC’s latest performance report, in 2006-2007 approximately 54,797 Aboriginal clients received assistance through the Strategy; of these 16,540 became employed or self-employed, and approximately 5,785 returned to school.[209] Each year, the AHRDS supports about 7,500 child care spaces.[210]

Other initiatives that complement the AHRDS include the Aboriginal Human Resource Council of Canada (a sector council) and the Aboriginal Skills and Employment Partnership (ASEP) program. The Council was established in 1998. Its goal is to develop career opportunities for Aboriginal people through partnerships with the private sector, Aboriginal organizations and various levels of government.[211] The ASEP program was introduced in 2003 as a five-year initiative with a budget of $85 million. As of February 2006, all of the funding for this initiative had been invested in nine projects established across the country.[212] It is estimated that these projects will result in over 5,000 Aboriginal clients being trained for over 3,000 long-term, sustainable jobs in various sectors, such as mining, oil and gas, forestry, construction and fisheries.[213] Budget 2007 has allocated an additional $105 million over five years to expand this program. It is anticipated that this increase will lead to 9,000 Aboriginal people receiving skills training and to 6,000 careers being created in major economic development projects.[214]

I noticed a doubling of the ASEP program in the budget. It's great and good news, but it's not even close to the amount of investment in human resources and human capital that is necessary to deal with that. If we don't make a financial and political shift, we're going to miss out enormously.[215]

Mr. Karl Flecker

Canadian Labour Congress

INAC offers two main programs to expand economic and employment opportunities for Aboriginal people. The Aboriginal Workforce Participation Initiative (AWPI) educates and informs employers about the advantages of hiring, retaining, and promoting Aboriginal people and works in partnership with various businesses and organizations to enhance the labour force participation of Aboriginal people throughout Canada.[216] The Procurement Strategy for Aboriginal Business (PSAB) helps Aboriginal firms do more contracting with federal departments and agencies. In 2006, 5,087 federal contracts worth $463 million were awarded to Aboriginal businesses.[217]

To support the development and enhancement of essential employability skills and to expose youth to work experience, INAC administers four programs offered under the First Nations and Inuit Youth Employment Strategy, a component of the federal government’s Youth Employment Strategy. These programs include the First Nations and Inuit Youth Work Experience Program, the First Nations and Inuit Summer Employment Opportunities Program, the First Nations and Inuit Science and Technology Program, and the First Nations and Inuit Career Promotion and Awareness Program. In 2006-2007, approximately 122,000 young Aboriginal people received support under the First Nations and Inuit Youth Employment Strategy.[218]

The federal government has also implemented a number of legislative measures to promote equality and safeguard people from discriminatory practices. Aboriginal people represent one of four designated groups whose under-representation in employment is covered under the Employment Equity Act. In addition, the federal government launched a Racism-Free Workplace Strategy as part of A Canada for All: Canada’s Action Plan Against Racism, initiated in 2005. Activities undertaken under this Strategy aim to remove discriminatory barriers to employment, job retention and upward mobility, and to promote a fair, productive and inclusive labour market. Aboriginal people and visible minorities are two groups that are particularly affected by racism in the workplace.[219]

Our second area of progress in the Labour Program is the Racism-Free Workplace Strategy. This strategy is vital to Canada's continued success, because in facing world markets, it ensures we are able to count on a highly competitive workforce that is uniquely rooted in diversity and inclusiveness. But let's be clear, this is the shared responsibility of employers, employees, government, business, and labour organizations. That's why this strategy is key. I recently completed a five-city tour to promote racism-free workplaces and the removal of barriers to employment and upward mobility for visible minorities and Aboriginal peoples. I announced our plan to hire nine anti-racism officers, whose mandate will be to work in the following three areas: to promote workplace integration of racial minorities — in other words, to be inclusive; to build a network between community resources and employers; and to provide tools and assistance to employers working toward equitable representation in their workforce.[220]

Hon. Jean-Pierre Blackburn

Minister of Labour

D. Closing the Gap in Socio-Economic Outcomes between Canada’s Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal People

Members of the Committee believe that the federal government must continue to invest in Aboriginal human capital and other initiatives that aim to close the gap in socio-economic outcomes between Canada’s Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal populations. The federal government must work in partnership with provincial and territorial governments, the business sector and Aboriginal organizations to create sustainable economic opportunities for Aboriginal people. We must ensure that Aboriginal children and youth have the necessary literacy skills, education, and training to meet current and future labour market demands. Aboriginal learners must be able to access, finance and complete apprenticeship programs and other post-secondary education programs. Innovative solutions must also be implemented to facilitate their transition from education to employment. Such innovations might include offering pre-employment training to provide information about the workplace culture and clarify employer expectations, as well as using Aboriginal employment role models or mentors to motivate young people to pursue an education or a particular career. Discriminatory barriers in the workplace that limit Aboriginal employment opportunities must be eliminated through measures such as campaigns to raise employers’ awareness of diversity issues. Other barriers to employment, such as the crisis in Aboriginal housing, relocation issues and the need for adequate funding for Aboriginal child care, must also be addressed to ensure that Aboriginal people have an equal opportunity to join the labour force. Federal programs and services offered to Aboriginal people and organizations must be culturally sensitive and inclusive.

Recommendation 3.6

The Committee recommends that Human Resources and Social Development Canada conduct a comprehensive evaluation, in full consultation with Aboriginal groups, of the Aboriginal Human Resources Development Strategy to assess the results to date and to determine whether the Strategy can: meet the needs of Aboriginal working parents (particularly single mothers); meet the needs of a rapidly growing young Aboriginal population that will reach working age in the near future; and achieve its long-term goal of raising the Aboriginal employment rate to a level comparable to that found among non-Aboriginal Canadians. Based on the results of this evaluation, the federal government should, if necessary, dedicate additional resources as needed, in particular by adopting long-term strategies of ten years to provide Aboriginal organizations, including band governments, planning and consultation time in the beginning years so they can take full advantage of the opportunities offered, and make any necessary modifications to the Strategy to enhance its effectiveness in meeting the employability needs of Aboriginal people.

Recommendation 3.7

The Committee recommends that the federal government, in partnership with provincial/territorial governments and Aboriginal stakeholders, take immediate steps to strengthen the commitment to provide high-quality, culturally relevant elementary and secondary education to Aboriginal students. Indian and Northern Affairs Canada should develop culturally sensitive measures and programs to reduce the high school drop-out rate among Aboriginal students and to better prepare students for post-secondary education. Pilot projects that would allow students to be linked with successful Aboriginal mentors should be used to strengthen school attendance and completion. The Committee recognizes the particular need to address education for First Nations and Aboriginal people from a lifelong learning perspective which includes: early childhood development; kindergarten to grade 12; post-secondary education; adult education and training. Part of this approach must include a commitment to build more schools on reserves to address the chronic lack of classroom space.

Recommendation 3.8

The Committee recommends that the federal government commit to better supporting Indigenous education institutions, taking into consideration the proposals in Budget 2008.

Recommendation 3.9

The Committee recommends that the federal government take the necessary steps to improve access to post-secondary education for Aboriginal people. Among other initiatives, the eligibility criteria for the Post-Secondary Student Support Program and the University College Entrance Preparation Program offered through Indian and Northern Affairs Canada should be broadened, and the budget for these programs should be increased and indexed to growth in the Aboriginal post-secondary school-age population. The federal government must continue to support the Indian and Northern Affairs Canada Post-Secondary Student Support Program and consider removing the two-per cent cap instituted in 1996.

Recommendation 3.10

The Committee recommends that the federal government, in collaboration with provincial/territorial governments and Aboriginal stakeholders, develop a program to raise awareness among Aboriginal people about the importance of, and economic benefits associated with, completing a post-secondary education.

Recommendation 3.11

The Committee recommends that Human Resources and Social Development Canada encourage the participation of Aboriginal people in trades-related training by working with Aboriginal stakeholders to examine initiatives and budgets geared specifically to meeting the needs of Aboriginal workers.

Recommendation 3.12

The Committee recommends that the federal government continue to support and implement fully the Racism-free Workplace Strategy to reduce discriminatory barriers to employment, promote a better understanding of Aboriginal cultural issues, and promote the socio-economic advancement of Aboriginal people.

Recommendation 3.13

The Committee recommends that the federal government, in partnership with other governments and Aboriginal stakeholders, develop innovative solutions to relocation problems that arise when Aboriginal people, especially youth and women, move to urban centres in search of employment.

Recommendation 3.14

The Committee recommends that the federal government examine the feasibility of developing incentive-based programs to encourage partnerships between employers operating near reserves and Aboriginal stakeholders that would foster training and employment opportunities on or near reserves.

Recommendation 3.15

The Committee recommends that the federal government, in partnership with provincial/territorial governments and Aboriginal organizations, develop a national Aboriginal housing policy to address the needs of Aboriginal people living on and off reserves. To maximize the socio-economic benefits of this policy, skills training should be provided to Aboriginal people who are interested in jobs related to residential construction, housing services and other occupations in the housing industry.

Recommendation 3.16

The Committee recommends that the federal government recommit to an Aboriginal Business Strategy, in which it would support Aboriginal economic development by setting fixed targets to make Aboriginal-owned businesses a preferred supplier of services and materials, especially in remote and northern regions.

In 2006, according to Statistics Canada’s Participation and Activity Limitation Survey (PALS), about 2.5 million Canadians aged 15 to 64 reported some form of disability, yielding a disability rate of 11.5% for the total working-age population.[221] As Canada’s population ages we can expect the proportion of people with disabilities to rise. The disability rate is higher among Aboriginal people: a recent report estimated that some 31% of Aboriginal people may have a disability.[222]

Studies have shown that, compared with adults without disabilities, Canadian adults with disabilities are less likely to have completed higher levels of education, less likely to be employed, and more likely to have a low income. In 2001, the most recent year for which national data have been published, 37% of persons with disabilities reported that they had less than a high school education. About 13% had a trades certificate or diploma, another 16% had a college education, and a little over 11% had a university education.[223] Among the population without disabilities, approximately 23% had a university education.

As we have seen in other groups in the labour market, the employment rate among people with disabilities increases with the level of education. However, many people with disabilities who have completed a post-secondary education have difficulty finding employment. In 2001, slightly more than 41% of working-age people with disabilities were employed compared with almost 74% of those without disabilities.[224] Despite this sizeable gap in employment rates between these two groups, the employment situation of people with disabilities has improved since 1999. For example, in the western provinces (Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta) where skills shortages are more acute, the employment rate for persons with disabilities has increased. Although people with disabilities are less likely to be employed in provinces with weaker economies, it should be noted that the employment rate among persons with disabilities living in those provinces has also increased in the last six years.[225]

In every sector in Alberta, we've seen businesses take on more folks from the non-traditional labour groups and have success in hiring them. The biggest increase has been among people with disabilities, with the number of firms having successfully hired them going from 16% to 27%. So they are moving in that direction.[226]

Ms. Corinne Pohlmann

Canadian Federation of Independent Business

Approximately 49% of working-age individuals with disabilities are not in the labour force. The Committee was told that a significant number of these individuals could work if it were not for the array of barriers they face (Statistics Canada estimates that in 2001 approximately 660,000 people with a disability could have worked).[227] The integration of these individuals into the workforce could help offset current and anticipated skills shortages. However, to achieve this goal, barriers to employment must be addressed. Those barriers include negative attitudes, inaccessible infrastructure and transportation services, a lack of education and training, a lack of accommodation in the workplace, and low availability and portability of disability-related supports.

One of the first findings that we can make is that a large percentage of persons with disabilities are currently inactive but feel they are able to work. However, these people say they experience problems of all kinds, such as negative perceptions by employers, transportation problems and a lack of training and experience. And yet persons with disabilities constitute a skilled labour force and are part of the response to the major labour shortage problem we are facing.[228]

Ms. Nancy Moreau

SPHERE-Québec

If we ensure that people have at least high school education, get back for some retraining, and get the disability supports they require — for example, the help from other people, technologies, wheelchairs, medications and so on — and if we ensure that the community transportation system is accessible for people, the chances are very good that the employment levels for people with disabilities will be very close to those of other Canadians.[229]

Mr. Cameron Crawford

Canadian Association for Community Living

They don't understand what they need to do to accommodate somebody with a disability. I think understanding that is the biggest barrier for them. Rather than trying to understand, they'd rather look elsewhere. In jurisdictions where they have no choice — and I think in Alberta you're seeing huge advancements in that particular area — employers are looking at people with disabilities more and more, because their options are fewer and they're making the accommodations they need. I think the biggest barrier is fear. They just don't know what they need to do to accommodate somebody with a disability.[230]

Ms. Corinne Pohlmann

Canadian Federation of Independent Business

1. Unmet Needs for Disability-Related Supports

Many witnesses indicated that the lack of accessibility to disability-related supports is a major barrier to employment. Disability supports are technical aids and devices, as well as human assistance, required by people with disabilities to accomplish the basic tasks of daily living. Without these supports, many people with disabilities are prevented from fulfilling their social and economic potential.

According to data collected from the 2001 PALS concerning people aged 15 and over who use assistive devices, 22% of those with moderate limitations, 33% of those with severe limitations and 50% of those with very severe limitations had unmet needs for specialized equipment. The main reason cited was cost (affecting 48% of those who needed help), while a lack of insurance coverage ranked second (affecting 36%).[231]

Human Resources and Social Development Canada (HRSDC) also reported that post-secondary students with disabilities have unmet needs for disability supports. In 2001, it was estimated that there were approximately 51,000 post-secondary students with disabilities, of whom 20% reported the need for disability supports to attend a post-secondary institution. Of these 10,000 students, only about 40% had their needs met, leaving approximately 6,000 students with disabilities with unmet needs for supports.[232]

Public coverage for aids and support devices is not available in all provinces and territories, and none of the provinces and territories provides access to the full range of disability supports. Eligibility for financial assistance to offset the cost of these supports is often linked to residency in a particular region or municipality, or to enrolment in public institutions (e.g., schools, residential facilities, etc.), and is based on income and eligibility for other benefits such as social assistance. Once a person leaves these settings, supports are generally withdrawn. This creates a disincentive to work, as the combined loss of income-tested benefits and disability supports often outweigh after-tax earnings from work. During our hearings, a number of witnesses raised this issue and argued that accessibility to disability supports should be universal, regardless of income or place of residence.

Some witnesses proposed the development of a more integrated and effective income and disability support system in Canada. The issue of a living wage was raised, since persons with disabilities are more likely to have a low income than persons without disabilities. In 2001, the average income of persons with disabilities aged 25 to 54 was 28% lower than that of similarly aged people without disabilities.[233] Several witnesses suggested that the federal government supplement the incomes of low-wage workers through the tax system by implementing a “working income tax benefit.” This measure, which has been discussed for several years, was finally introduced in Budget 2007. Under the Working Income Tax Benefit (WITB), a refundable tax credit is paid to low-income individuals who have annual earnings above $3,000. The maximum benefit for a low-income single individual is $500 (reached at $5,500), which is reduced at a rate of 15% when earnings reach $9,500. An additional supplement of $250 is paid to low-income workers who are eligible for the Disability Tax Credit.[234] In this case, the credit begins to accrue when the earnings of a single-earner with a disability reach $1,750, and the maximum credit is paid when earnings are between $5,000 and $10,000. The WITB is discussed further in this chapter in the context of low-income workers.

In terms of disability-related supports, it is the priority for persons with disabilities across the country, it is the priority of the national disability organizations, because an investment in disability-related supports makes economic sense. If we are facing a labour shortage, if we are facing a shortage in the trades, if we are requiring an influx of human resources into our employment sector, well, for God's sake, provide disability-related supports so that people with disabilities can participate.[235]

Ms. Marie White

Council of Canadians with Disabilities

For at least a decade now, the issue of disability supports hasn't been the only priority, but it's been the single most important priority within the disability community, and there's been virtually no progress on this file. This is a key result of there being a lack of engagement by federal and provincial/territorial partners in this area, which is an absolutely vital concern to the disabled community.[236]

Mr. Cameron Crawford

Canadian Association for Community Living

Provinces have remarked over the last number of years they think that about half the people on their social assistance rolls are people with disabilities. The reason I got a little confused is that we also estimate the number of people with disabilities currently on social assistance who tell us through surveys they would be able to work but there are things that get in the way, like transportation or employers not being able to provide accommodation, or even what we call the “welfare wall”, where people get disability supports while they're on social assistance, and then in some jurisdictions lose them as they earn income. That creates a disincentive for them to participate in the labour market.[237]

Ms. Caroline Weber, Office for Disability Issues

Department of Human Resources and Social Development

The Committee was also told that the integration of people with disabilities in the labour market requires greater access to transportation, learning establishments and workplaces, as well as accommodations on the job (e.g., modified and flexible work hours, technical equipment, modified workstations, etc.). Persons with disabilities require access to labour market information, skills training and employment assistance services to prepare for, find and maintain employment. Some witnesses stated that there are gaps in employment programming for people with disabilities who do not have a strong attachment to the labour market. The Committee also heard about the unique challenges of people with a mental illness and those with episodic and “invisible” disabilities. Their attachment to the labour force may be more sporadic, and they may require flexible work arrangements to maintain employment. Employers also require assistance. They need support in identifying and recruiting employees with disabilities as well as information on job accommodation and assistive devices.[238]

In the workplace there are a myriad of barriers for women with disabilities. Research which has looked at the employment support needs of persons with disabilities has shown that the need for “modified work structures” such as handrails/ramps, accessible transportation to and from work, parking, elevators, and washrooms, and modified work stations, is almost twice as high (28% versus 15%) among persons with disabilities who are unemployed as compared to persons with disabilities who are employed. This suggests that a person’s need for such modified workplace structures may make them more vulnerable to job loss and increase their difficulty in finding employment.[239]

Nova Scotia Advisory Council on the Status of Women

Of all persons with disabilities, those with a serious mental illness face the highest degree of stigmatization in the workplace and the greatest barriers to mainstream employment. Adults and youth with psychiatric disabilities face many and varied employment obstacles, such as gaps in work history, limited employment experience, lack of confidence, fear and anxiety, workplace discrimination and inflexibility, social stigma, and the rigidity of existing income support and benefit programs.[240]

Ms. Jodi Cohen

Canadian Mental Health Association

Many employers have moved from hiring because of a corporate social responsibility, to actually viewing persons with physical disabilities as strengthening their corporate resources and capabilities, and in some situations as creating a competitive advantage. Still, there are some employers, particularly medium or small employers, for whom this is not the case. In addition, where the disability is hidden, such as a mental health disorder or epilepsy, that progress has not been as evident.[241]

Mrs. Andrea Spindel

Ontario March of Dimes

Employers certainly admitted to us that they do not know where to find qualified people with disabilities, and seldom do they even reach out to service providers in their community. There is certainly a need, then, to increase awareness of disability issues in the employer community, as well as to help employers to be more forthcoming and open with workplace accommodation.[242]

Mr. Alar Prost

Innovera Integrated Solutions

B. Role of the Federal Government

Although witnesses recognized that provincial and territorial governments as well as the private and non-profit sectors have significant responsibilities with respect to enhancing employability among persons with disabilities, they underlined that the federal government also has an important “role to play in disability, in making employment available for people with disabilities, and in facilitating the development of an inclusive labour market.”[243] Many identified a need for a national labour-market strategy for persons with disabilities. Others emphasized the need for better collaboration on disability issues among all levels of government, non-governmental organizations and stakeholders. Some witnesses recommended the creation of a national disability act that would not only address the issue of employment but would also provide systemic solutions and mechanisms to advance the goals of full inclusion, participation and citizenship of persons with disabilities in Canadian society.

The Government of Canada must take the lead in forging a new labour market strategy, based on the tenets of full inclusion and universal design, that will more effectively address the historic level of unemployment and under-employment that continues to confront so many Canadians with disabilities.[244]

Alliance for Equality of Blind Canadians

The major initiative, I think, would be to look at a national disabilities act, which would require publicly funded organizations, institutions, crown corporations, and so on to make accessibility a higher priority and provide some funding and some incentive, and employer and institutional training, particularly human resource systems, but whole levels of the organization getting education about what they can do about it.[245]

Mrs. Andrea Spindel

Ontario March of Dimes

While our document recognizes that all levels of government and the private and non-profit sectors have a role to play, today we wish to emphasize the important role that the federal government needs to play as a catalyst for change, first — as our colleagues from the March of Dimes mentioned earlier — by setting the right context and framework through the establishment of a national disabilities act that would articulate national standards and definitions for many areas, including employment and income support, and would promote inclusion in all aspects of community life.[246]

Mr. Robert Collins

Partners in Employment-London/Middlesex

Recommendation 3.17

The Committee recommends that the federal government, in consultation with provincial and territorial governments and stakeholders, continue to develop and implement a national disability act to promote and ensure the inclusion of people with disabilities in all aspects of Canadian society.

Members of the Committee believe that the federal government must show leadership and, in collaboration with provincial/territorial governments and other stakeholders, support initiatives that remove barriers to labour force participation of persons with disabilities and that contribute to their integration into paid employment or self-employment. Over the years, the federal government has implemented a number of initiatives to achieve these objectives. This section of our report discusses some of these programs.

1. Human Resources and Social Development Canada Programs

HRSDC offers a number of programs to help persons with disabilities obtain and keep employment. Programs vary depending on whether an individual is eligible for Employment Insurance (EI) benefits. Federal funding is also distributed to provinces and territories to contribute to the costs of programs and services that increase employment opportunities for persons with disabilities.

Founded in 1997, the Opportunities Fund is a contribution program with an annual budget of $30 million. Most of this budget ($26.7 million) is spent on contribution agreements designed to help people with disabilities overcome barriers to employment. The remaining funds are spent on operating costs. To qualify for assistance under the fund, people with disabilities must not be eligible for EI (including Employment Benefits). Funding may be provided to cover the cost of participants’ wages or related employer costs, as well as overhead costs related to the organization, delivery, and evaluation of activities, including staff wages. Participants may also be eligible to receive contributions to cover all or part of the costs of various expenses, such as specialized services, equipment, dependant care, accommodation, transportation and tuition.[247]

Most witnesses who talked about the Opportunities Fund were very satisfied with the outcomes of this program. This finding is also supported by the results of an evaluation published in 2001, which showed that participants improved their skills, employability, self-confidence, self-esteem and quality of life. Employers and organizations also benefited from their participation in the fund. About one-third of employers saw a change in their organization’s attitude toward hiring persons with disabilities, and almost two-thirds hired at least one of the participants, mostly on a full-time permanent basis.[248] A second summative evaluation was undertaken in 2003. Preliminary results suggest that a majority of clients are satisfied with the program and that it continues to be relevant. The evaluation also showed “that the program fills a service gap in helping people with disabilities who are not well served by other federal or provincial government programs.”[249]

Despite the fact that the Opportunities Fund has a huge load to carry, its budget has not increased in the last decade. Therefore, its real value has declined. The Committee was told that the program has a waiting list. Considering the number of people with disabilities who are unemployed and ineligible for other federal labour market support, many witnesses recommended that the program’s budget be increased. Some witnesses also indicated that there is a need for longer-term interventions for those persons with disabilities who have been out of the labour market for long periods or who have never had a strong attachment to the labour market. As well, the need for flexibility in programming was raised by a few witnesses, particularly with respect to accommodating the unique needs of people with recurring or episodic disabilities who may require employment assistance over a longer period of time. We agree with our witnesses.

The Opportunities Fund is the only intervention available for those persons with disabilities who have had no EI attachment. This budget has been static since 1997. The $30 million allocated to this fund has been eroded by inflation and should be $36.5 million today to deliver the same level of service with no growth.[250]

Mr. Brian Tapper

TEAM Work Cooperative Ltd.

Quadruple the resources in the Opportunities Fund and expand its terms and conditions such that this critical federal instrument can more effectively support effective long-term interventions and skill development opportunities targeted primarily at those persons with disabilities who have multiple barriers to the labour force and as a consequence have become marginalized citizens of Canada.[251]

Neil Squire Society

Recommendation 3.18

The Committee recommends that the federal government increase funding for the Opportunities Fund and expand the terms and conditions of this program to support effective long-term interventions and skills development opportunities, especially with respect to essential skills training. A portion of the increased funding could be used to enhance the participation of employers and to provide employers and employees with knowledge about disability issues, accommodation in the workplace, and the tools available to create an inclusive workplace. Particular attention should be given to monitoring and reporting results to ensure that the program achieves its anticipated outcomes.

b) Multilateral Framework for Labour Market Agreements for Persons with Disabilities

The Multilateral Framework for Labour Market Agreements for Persons with Disabilities took effect on April 1, 2004. Under this framework, the federal government contributes to the costs of programs and services that improve the employment situation of persons with disabilities.[252] Provincial governments can determine their own priorities and approaches to address the needs of people with disabilities in their jurisdictions but they have agreed on a number of priority areas. These include education and training; employment participation and opportunities; bringing together employers and persons with disabilities; and building knowledge. The federal government contributes fifty per cent of the costs of the programs, up to the amount identified in each bilateral agreement. In 2005-2006, the federal contribution to participating provinces under these agreements was $218 million.[253] On November 22, 2007, the Minister of Human Resources and Social Development announced that the agreements would be extended until March 31, 2009 with an annual investment of $223 million.[254]

During our hearings, a number of witnesses questioned the success of Labour Market Agreements for Persons with Disabilities. Some suggested that there is a need to review and revise these agreements. Others argued that the level of funding is simply inappropriate and does not take into account the multiple barriers to employment that persons with disabilities need to overcome in order to participate in the labour market.

In 2003, the ministers responsible for social services approved the multilateral framework for labour market agreements for people with disabilities. It replaced what was then known as EAPD, or employability assistance for people with disabilities. While the goal of this framework is to improve the employability of Canadians with disabilities, it cannot do so at the current levels. The current funding levels are not adequate. We have an injection of funding in the 2003 budget of $193 million. It should be doubled, at the very least. That needs to occur because current labour market agreements don't take into account the situation of people with disabilities.[255]

Ms. Marie White

Council of Canadians with Disabilities

Other programs administered by HRSDC include Employment Benefits and Support Measures (EBSMs), the Canada Pension Plan Disability benefit, the Social Development Partnerships Program (disability component), the Aboriginal Human Resources Development Strategy (disability component) and programs that offer financial assistance for post-secondary education.

As discussed in Chapter 2 of our report, EBSMs are provided under Part II of the Employment Insurance Act. Eligible persons with disabilities may receive assistance through four employment benefits: Targeted Wage Subsidies, Self-Employment, Skills Development and Job Creation Partnerships.[256] A client-focused support measure is also offered through Employment Assistance Services. In 2005-2006, the rate of participation of persons with disabilities in EBSMs was 4.6%.[257] A number of witnesses argued that it is difficult for people with disabilities to accumulate the required number of hours to qualify for certain EI benefits as many do not have a strong attachment to the labour market. Some witnesses also questioned the effectiveness of these measures, as employers who hire persons with disabilities with the assistance of wage subsidies may terminate their employment once the funding is eliminated. An overview of results of summative evaluations conducted in different jurisdictions found that “EBSMs appeared to yield some modest positive net impacts on participants, depending on the program, client type and jurisdiction.”[258]

As the committee knows, labour market participation by people with disabilities is significantly lower than that by the mainstream population. Because the most effective federal government employment support programs are tied directly to people's attachment to the labour market and the EI system, many people with disabilities are ineligible and are therefore underserved.[259]

Mr. Bob Wilson

Social and Enterprise Development Innovations

Employers only willing to hire a person under a grant program, such as, Targeted Wage Subsidy may result in repeated periods of unemployment and short term employment. As soon as the funding is up, the person is let go and must start the job search all over again.[260]

Canadian Paraplegic Association

The Canada Pension Plan Disability (CPPD) benefit provides income protection to Canada Pension Plan contributors who cannot work because of a severe and prolonged disability. One of the program’s goals is to facilitate a return to work for those who are able to do so by offering the services of a vocational rehabilitation program.[261] Over the period 2003-04 to 2005-06, there has been a 39% increase in the number of CPPD recipients returning to work.[262]

The Social Development Partnerships Program (disability component) provides grants and contributions in support of national activities of non-profit social agencies working to address the social development needs and aspirations of persons with disabilities and to promote their inclusion and full participation as citizens in all aspects of Canadian society.[263] In 2005-2006, a portion of the $11 million allocated under this program was invested in employment-related projects for persons with disabilities.[264]