JUST Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

|

ENDING ALCOHOL-IMPAIRED DRIVING: A COMMON APPROACH In exercising its jurisdiction over criminal law, Parliament has enacted measures in the Criminal Code to prohibit and punish impaired driving. The Criminal Code also sets out the procedures to be followed to obtain the evidence necessary for prosecution of these offences. In addition to the measures taken by the federal government, the provinces and territories use their authority to regulate driver licensing and highways to impose provincial licence suspensions. Some provinces impound the vehicles of repeat impaired drivers and they impound cars being driven by persons who are prohibited from driving pursuant to the Criminal Code or have had their licence suspended by the province. The provinces are also responsible for prosecuting and implementing many provisions of the Criminal Code, as part of their jurisdiction over the administration of justice. The Criminal Code prohibits driving while one’s ability to operate a vehicle is impaired by alcohol or drugs. It is also an offence to drive with a Blood Alcohol Concentration (BAC) in excess of 80 mg of alcohol in 100 ml of blood. There are mandatory minimum penalties upon conviction for these offences with escalating penalties for repeat offenders. Furthermore, impaired driving causing bodily harm or death carries a significantly greater penalty. The Criminal Code enables police to demand a breath or blood sample where they have reasonable grounds to believe that a driver is impaired. Failure or refusal to provide a sample is an offence carrying the same penalty as driving with a BAC over the legal limit. The provinces and territories have instituted administrative penalties or controls that allow immediate action to be taken against suspected impaired drivers. One example of such measures is an automatic licence suspension that takes effect following failure or refusal of a breath test. This suspension is not dependent on there being a Criminal Code conviction. All jurisdictions except Québec have also implemented temporary preventive suspensions for drivers with a BAC that is considered elevated but still below the criminal limit set out in the Criminal Code. All provinces have adopted zero BAC limits for young or novice drivers as part of graduated driver licensing schemes. Thus, Canada has in place a three tier system of sanctions, depending upon the level of BAC:

Another enforcement tool is the seizure and impoundment of vehicles operated by a prohibited or unlicensed driver. In general, therefore, provincial and territorial legislation seems to aim toward a more swift and certain administrative action as a means of reinforcing the criminal penalties available under the Criminal Code, which take time to proceed with and which may or may not be implemented even where charges are laid. On July 2, 2008, new provisions of the Criminal Code concerning impaired driving came into force. As a result, there are now nine distinct offences related to impaired driving in the Criminal Code. These offences are:

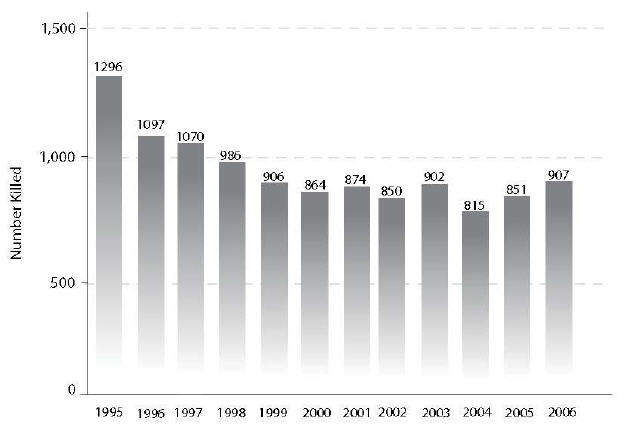

PREVALENCE OF IMPAIRED DRIVING Witnesses who appeared before the Committee made it clear that impaired driving remains the number one criminal cause of death in Canada. The Canadian Police Association indicated that, despite our collective best efforts and intentions, it is apparent that the problem of impaired driving is worsening in Canada and we are losing ground in our efforts to eliminate the problem. Mothers Against Drunk Driving stated that, since 1999, the progress in Canada on impaired driving has stalled. The scale of the problem of impaired driving is reflected in a survey of Canadians which indicated that almost one quarter (22.3%) of them — an estimated 7.5 million — know of a family member or close friend who has been the victim of a drinking and driving collision that they did not cause.[10] An estimated 5.4 million Canadians (16.5%) stated that they know of a family member or friend who was drinking and driving and caused a collision where they were at fault. The impact on the lives of Canadians includes serious physical and psychological injuries and the attendant health care costs, as well as the loss of family members and friends. In 2006, the most recent year for which data is available, 907 Canadians were killed in a traffic crash involving a drinking driver. [11] This represents a decrease from the 1,296 Canadians killed in 1995 but the number has been increasing since 2005. The data indicate that the decrease in the number of fatalities largely took place in the 1990s but the 2005 and 2006 data suggest that any progress that may have been made has since halted.

Source: Traffic Injury Research Foundation, The Road Safety Monitor 2008: Drinking and Driving National, http://tirf.ca/publications/PDF_publications/rsm2008_dd-nat_web.pdf Another suggestion that progress in the fight against drinking and driving has halted is the result of a survey of Canadians on the issue. 18.1% of Canadians admitted to driving after consuming any amount of alcohol in the past 30 days in a survey conducted in 2008. This represents an increase from 15.8% in 2003.[12] When calculating the financial costs of impaired driving, there are three types of questions that can be asked:

The average cost of impaired driving crashes in Canada from 1999 to 2006 has been calculated using the Real Dollar Estimate as approximately $1.9 billion per year. This figure is based on money spent, without considering any social costs. The average cost using the Willingness to Pay model is approximately $11.2 billion per year. This model includes money spent and a broad range of social-related costs.[13] The House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights adopted the following motion on February 9, 2009: That the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights do a full review of the issue of impaired driving including consideration of:

This motion was a reiteration of a motion first adopted on November 27, 2007 during the 39th Parliament. The dissolution of that Parliament prevented a report from being presented until now. As part of its study, the Committee heard from witnesses on the following dates: February 7, 2008, February 12, 2008, February 28, 2008, February 23, 2009, February 25, 2009, and March 2, 2009. The witnesses who gave evidence were the following:

BLOOD ALCOHOL CONCENTRATION LEVELS In 1969, an amendment to the Criminal Code made it a criminal offence to drive with a Blood Alcohol Content (BAC) of over 80 milligrams of alcohol per 100 millilitres of blood (0.08). That amendment also authorised the police to demand breath samples from suspected impaired drivers and made it an offence for suspects to refuse. In addition, all Canadian provinces (with the exception of Québec) maintain and enforce roadside administrative sanctions that immediately take drivers who have been drinking off the road where their BAC is above a certain level (usually 0.05) but below the Criminal Code level of 0.08. The suggestion has been made that the criminal BAC be lowered from 0.08 to 0.05.[14] There was testimony before the Committee to the effect that above the 0.05 level safe driving skills are impaired and collision risks are increased.[15] A lower criminal BAC level may not only reduce alcohol-related crashes and deaths, it may also positively change public attitudes about drinking and driving and make drivers more conscious of their drinking. Before we consider amending the law to reduce the criminal BAC from 0.08 to 0.05, however, we need to be certain that we are using the provincial and territorial administrative frameworks (which generally have a 0.05 BAC level) effectively and efficiently. While the Committee is eager to see fewer deaths and injuries on the road as a result of impaired driving, it is concerned about the lack of consensus among experts in the field as to whether or not a lower Criminal Code BAC limit would achieve greater safety. It is also cognizant of the finite resources available to enforce the laws on impaired driving. In addition, as noted below, there are possible negative effects of lowering the BAC limit in the Criminal Code. The Committee does recognise that impairment of driving ability can occur at BACs below 0.08. A study of alcohol use among fatally injured drivers, however, indicates that the bulk of the impaired driving problem lies with those drivers having a BAC over the current Criminal Code BAC limit of 0.08. Among the tested drivers in Canada, 62.9% showed no evidence of alcohol — 37.1% had been drinking, 4.3% had BACs below 0.05, 2.6% had BACs from 0.05 to 0.08, 9.4% had BACs from 0.081 to 0.160 and 20.8% had BACs over 0.160. In other words, 81.5% of fatally injured drinking drivers had BACs over the current limit of 0.08.[16] High-BAC drivers (i.e. those with BACs over 160 mg/100 ml of blood) represent a disproportionate number of fatally injured drinking drivers. High-BAC drivers represent about one percent of the cars on the road at night and on weekends yet they account for nearly half of all drivers killed at those times.[17] Limited resources would seem to be best deployed to target the 81.5% of the fatally injured drinking drivers that are already above the 0.08 threshold. The worst offenders are already driving with BACs two or three times the current limit and it would be naive to think they would comply with a lower limit. Drivers with the highest BACs constitute the most significant danger on the roads and they are still the priority.[18] Beyond the scientific evidence, a lowering of the Criminal Code BAC level would be difficult to implement at a practical level for a number of reasons. One negative effect of lowering the BAC limit in the Criminal Code would be to significantly increase the number of criminal prosecutions in Canada, putting additional stress on an already-burdened police and legal system. The justice system is already struggling to deal effectively with the current volume of criminal impaired driving cases. Caseloads for Crown attorneys are already substantial and impaired driving cases require a great deal of time to prepare and try due to the complexity of the issues. More than 40% of accused persons plead not guilty and proceed to trial. Plea agreements are less common than in other areas of criminal law for a number of reasons. One is that the conviction rate at trial is rather low (approximately 52% nationwide compared to overall conviction rates two decades ago in excess of 90%).[19] A second reason is that the consequences of a conviction are severe, ranging from having a criminal record to mandatory, lengthy driving prohibitions. A third reason is that automobile insurance, which is usually mandatory, may become more expensive if there is a criminal conviction on one’s record. The high number of prosecutions that proceed to trial means that the specific deterrent effect of impaired driving laws is eroded as accused persons are able to continue to drive for substantial periods following arrest and prior to conviction. In other words, there may be no swift and certain punishment when criminal charges are laid. It is estimated that by lowering the legal BAC an additional 75,000-100,000 impaired driving cases would be added to the current caseload of more than 50,000 criminal cases annually.[20] The number of criminal impaired driving cases, therefore, could increase by 100%, requiring immense resources to manage. This would essentially overwhelm the justice system and seriously impair the ability of the Crown and the courts to deal effectively with these cases. This would erode the specific and general deterrent effects of impaired driving laws by further reducing the swiftness with which high-BAC cases are processed as well as the certainty of sanctions being applied. It also raises a question regarding what would happen to all of the provincial programs that are now in place. A further problem with lowering the Criminal Code BAC is that, along with fewer resources being applied to each case, it would take longer to resolve these cases. Aside from reducing the speed of the criminal justice system, there would be no guarantees that the end result would be satisfactory. As a function of coping with the influx of new cases, Crown attorneys may be forced to accept plea agreements that are not appropriate, to plead cases that should proceed to trial, and to lose cases that do go to trial due to a lack of preparation time and other resources. This helps to explain why less than half (40%) of Crown prosecutors support lowering the legal BAC limit.[21] Based on the evidence presented to it, it appears to the Committee that the potentially negative consequences associated with “net widening” and bringing more impaired drivers into criminal court would likely outweigh any potential traffic safety benefit that may result from a lower Criminal Code BAC limit. A risk in reducing the criminal limit to a point where it cannot be enforced in a practical way is that this would damage the specific and general deterrent effects of impaired driving laws and reduce the public’s respect for them. It should also be kept in mind that all provinces except Québec already apply sanctions when a BAC is found to be between 0.05 and 0.08. These provincial measures can be applied such that drivers who have been drinking are removed from the road immediately. This is in contrast to the 2 to 3 hours required to process a criminal impaired driving arrest, along with the many months before any criminal sanction is imposed. The potential lowering of the BAC level in the Criminal Code was examined by this Committee in its 1999 report entitled Toward Eliminating Impaired Driving.[22] At that time, the Committee rejected proposals to lower the Criminal Code BAC limit to 0.05. The Committee concluded that a legal BAC of 50 mg/100 ml of blood could result in a loss of public support, since scientific evidence suggested that not everyone would be impaired at that level. In addition, the Committee found that a legal level of 0.05 would be difficult for police to enforce, given the lack of overt signs of intoxication at BAC levels below 80 mg/100 ml of blood. The Committee was also cognizant of the fact that the provinces would bear the additional enforcement burdens, as well as the practical consequences, that would flow from such a policy shift. This Committee shares these concerns with lowering the Criminal Code BAC level. It believes that what is needed is to increase the perception of apprehension, and to improve the system's efficiency and effectiveness in dealing with impaired offenders. Short-term suspensions are not necessarily a severe sanction, but they are applied swiftly and with certainty at the time of the offence — factors deemed essential to effective deterrence. They also eliminate the potential danger of having a drinking driver on the road. Criminal sanctions may be more severe but they are often so far removed from the behaviour as to weaken their impact. A more aggressive, co-ordinated effort amongst the provinces to strengthen roadside suspension programs would appear to be a cost-effective way of deterring motorists who may consider driving with some level of impairment, allowing the courts to focus time and effort on those cases where much higher levels of impairment were found. Section 255.1 of the Criminal Code states that if an impaired driving offence is committed by someone whose BAC exceeded 0.16 at the time the offence was committed, this will be an aggravating factor on sentencing. This reflects the fact that driving with a high level of impairment (over 0.16 BAC or double the current legal limit) is generally indicative of serious problems. Even if a driver with this level of impairment is being detected for the first time, it is likely that this is a hard-core impaired driver. This is due to the fact that it is rarely the first time they have driven while impaired by alcohol — it is simply the first time they have been arrested for it.[23] The Committee thinks that we can go further in targeting drivers with high BACs by introducing specific penalties for such drivers. The goal of such tiered penalties would be to prevent these drivers from re-offending, since high risk offenders cause a greater number of collisions with higher fatality rates and are more likely to be repeat offenders.[24] The Committee also heard testimony about the possibility of introducing a third offence in the Criminal Code, namely that of a breath (not blood) alcohol concentration that exceeds 80 milligrams of alcohol in 210 litres of breath. The breath alcohol concentration in the recommendation is the exact equivalent of 80 milligrams of alcohol in 100 millilitres of blood. This is what breath-testing instruments actually calculate and this is then transcribed into a blood alcohol concentration. While this would eliminate many of the defences around variability in what is called the blood-breath ratio, which is that an individual’s blood alcohol concentration was greater than 80 mg/100 ml of blood but due to physiological properties they might actually have been below the legal limit, the Committee is not in favour of creating a new offence for two reasons. One is that the Criminal Code provisions concerning impaired driving are already complex and do not need the added weight of a new offence. Secondly, the new generation of breath-testing equipment, such as the Intoxilyzer, will hopefully eliminate technical disputes as to whether the breath sample taken provides an accurate measure of the amount of alcohol in the blood. Recommendation 1: The Committee recommends that the Blood Alcohol Concentration level in the Criminal Code of eighty milligrams of alcohol in one hundred millilitres of blood be maintained. Recommendation 2: The Committee recommends that the provinces and territories be encouraged to enhance their efforts in intervening at BACs lower than the Criminal Code level. Recommendation 3: The Committee recommends that tougher sanctions be introduced for repeat impaired drivers. Recommendation 4: The Committee recommends that tougher sanctions be introduced for those drivers with a Blood Alcohol Concentration in excess of 160 milligrams of alcohol in 100 millilitres of blood. In Canada, under provincial and territorial legislation, police are allowed to stop a vehicle to check the vehicle’s condition, the driver’s licence, and condition of the driver, including his or her sobriety. However, police may not request a breath sample using an approved screening device unless the officer reasonably suspects that the driver has alcohol in his or her body. This, however, is not always practical and there are no reliable means of detecting alcohol consumption by observation alone. The detection of alcohol can be a difficult task, especially in a brief interaction at the side of the road. If an impaired driver escapes detection at a checkpoint, it can serve to reinforce drinking and driving behaviour and increase the likelihood of its recurrence. Random breath testing (RBT) would allow police officers to request a breath sample at any time in the absence of reasonable suspicion or reasonable and probable grounds. This would serve to recognise that driving on Canadian roads is a privilege and not a right. RBT would, therefore, introduce a significant deterrence for people who might otherwise choose to take the chance and drive while impaired. A number of arguments in support of RBT were made by witnesses who testified before the Committee. One argument was that, although the threshold for suspicion is not high, there is research indicating that many impaired drivers are able to avoid a demand for a breath test when stopped by the police because the officer does not detect the smell of alcohol or symptoms of impairment. Those drivers who do not show signs of impairment and thereby avoid a demand for a breath test would be more likely to be detected by RBT. In other words, the current methods of enforcing the law lead police officers to apprehend only a small percentage of impaired drivers, even at roadside traffic stops designed to detect impaired driving. This also does not speak well for the deterrence effect of Canada’s impaired driving laws. Secondly, it should be kept in mind that only a small fraction of drinking drivers (estimated at between 1/500 and 1/2000) is apprehended.[25] The goal of RBT is to increase the probability of an impaired driver coming into contact with the police and, therefore, increase the risk of being caught. Because everyone is required to provide a breath sample under RBT, the perceived risk of detection is much higher than the present situation where the police have to form a suspicion of alcohol in the body. With a higher percentage of impaired drivers being detected, more individuals may be deterred from driving while impaired as the effectiveness of deterrence depends on the perception of the risk of being stopped. With fewer people driving while impaired, fewer people would be injured or killed in impaired driving accidents. Another argument in favour of RBT is the experience of other countries. RBT came into force in Ireland in July 2006 and was credited by the Road Safety Authority with reducing the number of people killed on Irish roads by 23%.[26] A number of Australian states have adopted RBT and various analyses of the programs have shown its worth. One study of the introduction of RBT in New South Wales showed a decrease of 36% in the number of fatally injured drivers with a BAC over the legal limit (0.05) in the first four years of the program. The study also showed a significant decline in the number of people saying they drove while believing they had a dangerous BAC level.[27] Publicising RBT programs through the media was found to further enhance the deterrence effect.[28] A further argument in support of RBT is that it has the advantage of raising police presence in a region when the program is in place. This police presence has been associated with a corresponding decrease in other criminal behaviour. This is due to the fact that a vehicle is often used in criminal enterprises and so the participants in these activities would wish to avoid police attention.[29] In addition to the arguments in support of RBT that were presented to the Committee, it seems that this measure to reduce impaired driving has the support of a majority of Canadians. In a survey commissioned by Transport Canada/MADD Canada, 66% of Canadians agreed that police should be allowed to randomly require all drivers to give a breath test to help detect impaired driving.[30] One caveat that must be raised when it comes to the proposed adoption of RBT is the possibility of it being challenged under section 8 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which states that everyone has the right to be secure against unreasonable search or seizure and under section 9, which states that everyone has the right not to be arbitrarily detained or imprisoned. By its very name, random breath testing indicates that it is not based on the reasonable suspicion that a driver has consumed alcohol but is carried out purely at random. At face value, this would appear to be an “unreasonable” search and an “arbitrary” detention, contrary to the Charter. Thus, a random breath test may have to be justified under section 1 of the Charter, which guarantees that the rights set out in the Charter are subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society. The case of R. v. Oakes[31] set out the tests that should be applied during a section 1 analysis. First, the objective of the law in question must be one related to concerns which are pressing and substantial in a free and democratic society. Secondly, it must be shown that the means chosen are reasonable and demonstrably justified. This second part is described as a proportionality test, which requires the party supporting the law to show three things:

The Committee is aware that there can be no guarantees when it comes to Charter litigation. Such matters often involve a difficult and complex balancing of rights and interests. In the case of RBT, the Committee has been persuaded that the first part of the section 1 test may be satisfied by the abundant evidence showing that impaired driving is a significant health, social and economic problem and that, as outlined previously, progress in reducing the damage caused by impaired driving has stalled. The Supreme Court of Canada has recognised the role of the criminal law in fulfilling this part of the section 1 test, stating “There is no question that reducing the carnage caused by impaired driving continues to be a compelling and worthwhile government objective.”[32] As for the second part of the test, the evaluations of RBT used in foreign jurisdictions have shown that there is a rational connection between a law to introduce such a program and the objective of reducing alcohol-related road collisions. Rights are impaired as little as possible since the stop and request for breath is brief and non-invasive (unlike, for example, the taking of a blood sample). Finally, in terms of proportionality between the objective and the limitations, the goal of reducing the many types of damage related to impaired drivers is significant and the effort required by drivers to contribute to a solution is minimal. An additional argument that can be made in the section 1 debate is that drivers on Canadian roads are already subject to random stops and searches under provincial highway traffic laws. This type of random stop has already been examined and approved by the Supreme Court of Canada as a reasonable limit prescribed by law.[33] Given that these searches are meant to determine whether a vehicle is safe to drive, it would not appear to the Committee to be that much more of an extension of the law to allow police to determine if the driver is safe to drive as well. Recommendation 5: The Committee recommends that random roadside breath testing be put in place. Alcohol Ignition Interlock Devices One of the advances in technology that can help to reduce the incidence of impaired driving is the alcohol ignition interlock device. When this device is installed in a motor vehicle, a driver must provide a breath sample before it will start. If the breath sample shows that the driver has a BAC in excess of a pre-set limit, the ignition will lock and the vehicle cannot be started. The available evidence clearly shows that impaired driving and recidivism are significantly reduced while these devices are installed on an offender’s vehicle.[34] Currently, a court may authorise the offender to operate a motor vehicle equipped with an alcohol ignition interlock device during the driving prohibition period if the offender registers in an alcohol ignition interlock device program established by a province or territory. All provinces have established such a program. Section 259 of the Criminal Code imposes mandatory driving prohibitions of one year for a first offence, two years for a second offence, and three years for each subsequent offence. In making such an order, however, a court may authorise the offender to operate a motor vehicle equipped with an alcohol ignition interlock device during the prohibition period. Even if such a device is installed, subsection 259(1.2) still requires that there be no reduction in the driving prohibition period below three months (for a first offence), six months (for a second offence) and 12 months (for each subsequent offence). In other words, an alcohol ignition interlock will reduce the length of the driving prohibition period, but not eliminate it altogether. The evidence presented to the Committee demonstrated the beneficial effects of using alcohol ignition interlocks. Research has shown that the device, which is installed at the offender's expense, can reduce recidivism by 50 to 90%.[35] This sanction is more easily enforced than traditional sanctions, such as licence suspensions, while still permitting offenders to remain employed and fulfil family responsibilities. An interlock serves as a constant reminder of the problem behaviour that needs correction because they are both an inconvenience to offenders as well as a cost. Increased use of alcohol ignition interlock devices could enhance public protection while offering meaningful deterrence to individual offenders. One problem with alcohol ignition interlocks is that there is no national standard for these devices. The Alcohol Test Committee of the Canadian Society of Forensic Science is responsible for approving Approved Screening Devices and Approved Instruments but not ignition interlocks, as those programs are within provincial/territorial jurisdiction. In order to improve national consistency and elevate the technical standard for these devices, it would be beneficial if the Alcohol Test Committee could be given responsibility for approving specific ignition interlock devices as meeting an approved standard, as is the case with Approved Screening Devices and Approved Instruments. Recommendation 6: The Committee recommends that the use of alcohol ignition interlock devices be encouraged. Recommendation 7: The Committee recommends that the Alcohol Test Committee of the Canadian Society of Forensic Science be authorised to approve alcohol ignition interlock systems for use in provincial and territorial programs. PROVINCIAL/TERRITORIAL MEASURES As stated earlier in this report, impaired driving is dealt with at both the federal and provincial/territorial levels in Canada, by means of criminal and administrative sanctions, respectively. Section 253 of the Criminal Code sets out the federal, criminal law approach to the issue by making it an offence to drive when the concentration of alcohol in the driver’s blood exceeds 80 milligrams of alcohol in 100 millilitres of blood. In addition to any other punishment, section 259 of the Code obliges a court to impose a driving prohibition order of at least one year’s duration. An exception is made where a province has an alcohol ignition interlock device program, in which case the offender may operate a vehicle equipped with the device while registered in the program, if authorised by the court. To complement the federal criminal provisions, each province and territory has enacted its own BAC limit with accompanying administrative sanctions, in the form of a driver’s licence suspension. The following table provides an overview of the administrative sanctions and BAC levels set by the provinces and territories.[36]

Source: Canada Safety Council, Canada’s Blood Alcohol Laws — an International Perspective, March 2006, available at: http://www.safety-council.org/info/traffic/impaired/BAC-update.pdf (updated by the author). One issue that arose among Committee members in discussions of provincial and territorial legislation is that of the minimum age for purchasing and consuming alcohol. Minimum purchase age laws are only effective if they are strictly and consistently enforced in all situations. This is not currently the case in Canada, where Alberta, Manitoba, and Québec set their minimum purchase ages at 18, while the rest of Canada sets the age at 19. The Committee has concluded that harmonising minimum purchase ages across jurisdictions would help reduce certain risky drinking behaviours. One example of such a behaviour is where significant numbers of young people cross provincial or territorial boundaries to take advantage of less restrictive regulations in neighbouring jurisdictions. This problem can be especially acute at certain border points where alcohol outlets and licensed establishments cluster to meet the demand from cross-border customers. Recommendation 8: The Committee recommends that the provinces be encouraged to co-ordinate provincial legal drinking ages to reduce the practice of cross-border drinking and driving. Parliament has the ability to provide principles to guide the courts when they are applying the Criminal Code provisions related to impaired driving. A statement of principles might start by emphasising that driving is a privilege and not a right. It could go on to say that it is in the interest of the safety of everyone that those who endanger the lives of others by driving impaired must be subject to swift, certain and severe criminal penalties. The continuing problem of impaired driving is a serious one and must be addressed urgently by the courts. In carrying out their functions, the courts must recognise that there is a direct relationship between impaired drivers and collisions and the severity and risk of collisions increases as the concentration of alcohol in the blood increases. The criminal law has an important role to play in communicating a certain message — impaired driving is unacceptable at all times and in all circumstances. Recommendation 9: The Committee recommends that Parliament provide guidance to the judiciary through a legislative preamble or statement of principles, which acknowledges the inherent risks of impaired driving and the importance of meaningful and proportionate consequences for those who endanger the lives of others and themselves. In 1999, the Criminal Code was amended to increase from two to three hours the time period within which the police could demand evidentiary breath and blood samples from suspected impaired drivers. Yet the breath and blood analyses are still only presumed to reflect the suspect’s BAC at the time of the alleged offence if the samples are taken within two hours. This time constraint can be problematic for a police officer if the arrest occurred in a rural area or when he or she was quite busy with other tasks such as assisting crash victims or securing an accident scene. A presumption of identity up to three hours would relieve the prosecutor of the time-consuming and costly obligation of calling a toxicologist in each impaired driving prosecution where the samples were taken outside of the time limit. Recommendation 10: The Committee recommends that the presumption of identity in subsection 258(1)(c)(ii) of the Criminal Code be extended from two to three hours. [1] ss. 253(1)(a) [2] ss. 253(1)(b) [3] s. 254(5) [4] s. 255(2) [5] s. 255(2.1) [6] s. 255(2.2) [7] s. 255(3) [8] s. 255(3.1) [9] s. 255(3.2) [10] Traffic Injury Research Foundation, The Road Safety Monitor 2008: Drinking and Driving National, http://tirf.ca/publications/PDF_publications/rsm2008_dd-nat_web.pdf [11] Ibid. [12] Ibid. [13] MADD Canada, Estimating the Presence of Alcohol and Drug Impairment in Traffic Crashes and their Costs to Canadians: 1999 to 2006, February, 2009, http://www.madd.ca/english/research/estimating_presence.pdf [14] Letter from the Canadian Medical Association, March 4, 2009 [15] Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Reducing Alcohol-related Deaths on Canada’s Roads, Presentation to the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, February 12, 2008 [16] Traffic Injury Research Foundation, Alcohol-Crash Problem in Canada: 2006, January 2009 [17] Canada Safety Council Presentation to the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights: Comprehensive Review of Matters Related to Impaired Driving, February 12, 2008 [18] Louise Nadeau, Brief to the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, February 7, 2008 [19] Traffic Injury Research Foundation, Recommendations for Improving Federal Impaired Driving Laws, Submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, March 2009 [20] Ibid. [21] Ibid. [22] House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, Toward Eliminating Impaired Driving, Ottawa, May 1999 [23] Table québécoise de la sécurité routière, Improving Road

Safety : Initial Report of Recommendations, [24] Canadian Automobile Association, Statement of Policy 2007-2008, Recommendation 6.3.6 [25] Louise Nadeau, Brief to the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, February 7, 2008 [26] Department of Justice, Impaired Driving Issues, Brief Submitted to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, February 2008 [27] MADD Canada, Reform of the Federal Law Concerning Impaired Driving: The Next Steps, Submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, March 2, 2009 [28] Insurance Bureau of Canada, Submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, February 27, 2009 [29] The Canadian Council of Motor Transport Administrators (CCMTA) Submission to the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights Regarding Impaired Driving, February 2008 [30] Impaired Driving Survey for Transport Canada/MADD Canada, prepared by Ekos Research Associates Inc., December 2007, http://www.madd.ca/english/news/pr/TP%2014760%20V2%20E.pdf [31] [1986] 1 S.C.R. 103 [32] R. v. Orbanski ; R. v. Elias, [2005] 2 S.C.R. 3, para. 55 [33] R. v. Ladouceur, [1990] 1 S.C.R. 1257 [34] Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Reducing Alcohol-Related Deaths on Canada’s Roads, Presentation to the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, February 12, 2008 [35] Traffic Injury Research Foundation, Ignition Interlocks: From Research to Practice: A Primer for Judges, July 2006 [36] It is important to note that this table deals with the administrative sanctions associated with the provincial or territorial limit established for BAC levels. Some provinces also have particular administrative sanctions associated with .08 BAC levels. Some laws also allow for vehicle seizure in certain cases. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||