COOP Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

STATUS OF CO-OPERATIVES IN CANADABACKGROUND TO THE STUDYOn December 18, 2009, the General Assembly of the United Nations (UN) resolved to proclaim 2012 the International Year of Co-operatives. That resolution, which recognized the contribution of co-operatives to economic development and social innovation around the world, was supported by Canada.[1] United Nations proclaim international years to draw attention to fundamental issues. In proclaiming 2012 the International Year of Co-operatives, the UN urged governments to create a supportive environment for the development of co-operatives and to stimulate their contributions to the overall environment in which they operate. In this context, the House of Commons unanimously adopted the following motion on May 30, 2012: That, a special committee be appointed to consider the status of cooperatives in Canada and to make recommendations by: (a) identifying the strategic role of cooperatives in our economy; (b) outlining a series of economic, fiscal and monetary policies for strengthening Canadian cooperatives as well as for protecting the jobs they create; (c) exploring the issue of capitalization of cooperatives, its causes, effects and potential solutions; (d) exploring whether the Canada Cooperatives Act of 1998 requires updating; (e) identifying what tools the government can use to provide greater support and a greater role to Canadian cooperatives; and that the committee consist of twelve members which shall include seven members from the government party, four members from the Official Opposition and one member from the Liberal Party, provided that the Chair is from the government party; that in addition to the Chair, there be one Vice-Chair from each of the opposition parties; that the committee have all of the powers of a Standing Committee as provided in the Standing Orders, as well as the power to travel, accompanied by the necessary staff, inside and outside of Canada, subject to the usual authorization from the House; that the members to serve on the said committee be appointed by the Whip of each party depositing with the Clerk of the House a list of his or her party’s members of the committee no later than June 8, 2012; that the quorum of the special committee be seven members for any proceedings, provided that at least a member of the opposition and of the government party be present; that membership substitutions be permitted to be made from time to time, if required, in the manner provided for in Standing Order 114(2); and that the Committee report its recommendations to this House no later than November 30, 2012. The Special Committee on Cooperatives met in Ottawa on July 10 and from July 24 to 27, hearing from a total of 46 organizations. The Committee also received more than 60 written documents from the co-operative sector stakeholders. This report provides a summary of that evidence and contains recommendations to the Government of Canada. The report’s structure is based on the motion adopted by the House of Commons, and the recommendations to the Government of Canada are presented in the report’s conclusion (Chapter V); the report’s four other chapters provide background to those recommendations. Chapter I describes the strategic role of co-operatives in the Canadian economy. Chapter II examines the fiscal and monetary issues respecting co-operatives in Canada, while the issue of access to funding for co-operatives is addressed in Chapter III. Chapter IV discusses certain legal issues associated with Canadian co-operatives. CHAPTER I — STRATEGIC ROLE OF CO-OPERATIVES IN THE CANADIAN ECONOMYA. Co-operatives: Definitions and PrinciplesCo-operatives and credit unions are driven by both economic and social concerns[2] and differ from individual businesses and corporations in the following three ways:[3]

Co-operatives around the world operate in accordance with the seven basic principles of the co-operative movement, which are:

The principles cited above are universal in that they generally apply to the co-operative movement as a whole. One witness offered an interesting microeconomic perspective on these principles that illustrated the difference between the co-operative model and the corporate model with respect to the redistribution of profits and corporate governance: In our case, the cooperative pays its members for their work, namely, the processing of milk that comes from farms and is delivered to the cooperative. When the cooperative has served all its customers, it shares the surplus earnings based on the work done on the farm and the volume of milk produced. An investor-owned business will remunerate the capital. Regardless of the industry, whether you are a financier or an investor, the company will pay back the capital that you invested in it. That is an important difference. What is more, our cooperative’s board of directors is made up of 15 members. In order to be a member of the board, a person must be a dairy farmer who is a member of the cooperative. This ensures that the members are able to control the fate of the cooperative based on their needs, namely the processing of their milk, in order to obtain capital gain.[5] B. National OrganizationsThe Canadian Co-operative Association and the Conseil canadien de la coopération et de la mutualité are the two main associations representing co-operatives in Canada. The Canadian Co-operative Association represents co-operatives operating in anglophone regions, while the Conseil canadien de la coopération et de la mutualité represents those in francophone areas. The mission of both associations is to promote the co-operative model, support the development of co-operatives and represent co-operatives to government. A number of federal government departments and agencies play a role with regard to co-operatives:

The Rural and Co-operatives Secretariat was established in 1987 and reports to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. It advises the government on policies affecting co-operatives, coordinates the implementation of such policies and encourages use of the co-operative model for the social and economic development of Canada’s communities. The Secretariat also provides a link between the co-op sector and the many federal departments and agencies with which they interact.

Industry Canada is responsible for developing federal legislation for the incorporation of federal bodies corporate other than financial institutions. The Department is responsible for the Canada Cooperatives Act.[6] Corporations Canada, which is part of Industry Canada, is responsible for administering the Act and for co-operative incorporation.

Finance Canada is responsible for federal legislation relating to financial institutions under federal jurisdiction. This includes the Cooperative Credit Associations Act,[7] under which credit co-operatives may be incorporated, and the Insurance Companies Act,[8] under which mutual insurance companies, among others, may be incorporated. The Department is also responsible for the Bank Act[9], which will allow the formation of credit unions once the necessary regulations are adopted and implemented by the government.

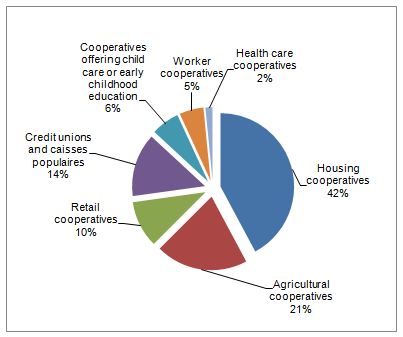

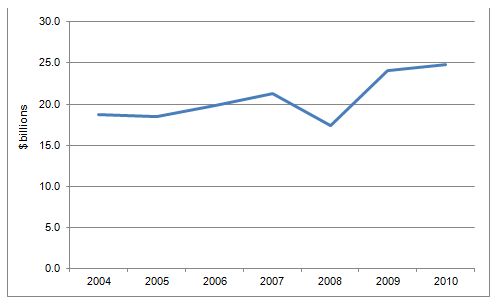

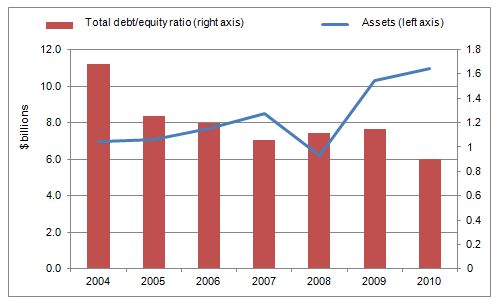

The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions oversees financial institutions under federal jurisdiction and ensures that they comply with the acts governing them. In that capacity, it administers the Cooperative Credit Associations Act, the Insurance Companies Act and the Bank Act, and is responsible for incorporating federal credit co-operatives and mutual insurance companies. C. Strategic Roles of Co-operatives in the Canadian Economy1. An Economic ForceCo-operatives play an important role in many sectors of Canada’s economy. Although traditionally prominent players in the agricultural and financial sectors (credit unions and caisses populaires), they have also been involved for some time in a number of other sectors, such as retail, housing, child care, telecommunications, funeral services and, in the past few years, health, and arts and culture. More recently, they have entered new areas such as renewable energy and fair trade.[10] Canada’s 8,500 co-operatives and credit unions have more than 17 million members. Figure 1 provides a breakdown of the number of co-operatives by area of activity. Housing co-operatives form the largest category (42% of the total number), followed by agricultural (21% of the total) and retail co-operatives (10%). Some 150,000 people work for Canada’s co-operatives, which own total assets of approximately $330 billion.[11] Figure 1 — Co-operatives in Canada by Area of Activity Source: Canadian Co-operative Association, The Power of Co-operation: Co-operatives and Credit Unions in Canada, Ottawa. One way to assess the impact of co-operatives is to ask the hypothetical question: what would the consequences be if co-operatives (or any equivalent form of organization) did not exist? According to the Centre for the Study of CO-OPs of the University of Saskatchewan, the implications of that absence for the economic and social development of the Prairies would be significant, including:

Co-operatives play a similar important role in many regions and communities across the country. For example, more than 1,100 Canadian communities have no financial services apart from those provided by a credit union or caisse populaire.[13] In addition, co-operatives in rural and outlying areas often succeed where other forms of business fail or are absent. Co-operatives are thus an essential economic driver for many communities in Canada: We especially wish to emphasize the fact that cooperatives and mutuals fuel job creation, innovation, financial stability and access to community-based services. Cooperatives and financial cooperatives often operate in sectors and communities that are underserved by traditional businesses.[14] I don’t have any problem with making the same things available to other companies, but we just happen to know that cooperatives are the ones that will survive in these rural communities where others won’t.[15] Many Canadian northern communities rely on the services of co-operatives to supply them with goods and services of all kinds. The Arctic co-operative system has demonstrated uncommon resilience: The co-op system in the Arctic is a model of community economic development. These co-ops, while small in comparison to businesses in other parts of Canada, are major economic engines in the communities of the north. The early years were very difficult and development of the local co-ops was very slow and the network struggled to survive. But consistent with the experience of co-ops in other parts of Canada, the survival rate for co-ops in the Arctic is exceptional. If we look at the 26 co-ops that signed the incorporation documents of Arctic Co‑operatives in 1972, 40 years ago, 77% of those co-ops continue in business today.[16] Co-operatives thus play an essential role in the economic development of many Aboriginal communities. The co-operative model was adopted in several communities because it is consistent with the traditional life of Aboriginal people.[17] Co-operatives occupy a strategic position particularly in the marketing of Aboriginal crafts, thus enabling this sector to better absorb economic ups and downs: Unfortunately, art marketing is something that when the economy goes up the market goes up, and when the economy goes down we see the market going down. But because cooperatives have been there, we have been able to provide that stability in the market. If we weren’t there, we don’t know that the industry would be in the position it’s in today. It is experiencing difficult times because of the economic conditions, but it continues. Would it have continued if there was not stability?[18] In addition, as a force for economic development, co-operatives are a strategic asset for official language minority communities in Canada: Cooperatives were born of the desire of a group of individuals to fulfill a collective need, and who pooled their skills and resources to that end. In so doing, they acquired means and expertise to which they would not otherwise have had access. In Canada, this practice was historically one of the cornerstones on which French-language communities, including those constituting official language minorities, were built.[19] We suspect that 15 to 20 cooperatives operate in French in Nova Scotia. Eleven of that number are established in the Acadian region of Cheticamp.[20] 2. An Alternative Force for Economic DevelopmentCo-operatives have often emerged in response to the imperative of meeting a community need, whether economic, social or cultural. Consequently, many co-operatives have flourished in tough economic times, when meeting such needs was a matter of particular urgency. This is illustrated by the following excerpts from testimony. On Prince Edward Island, the beginning of the cooperative movement can be traced to 1864 and the Farmers’ Bank in Rustico. The bank was started by the poorest of the poor, the Acadian farmers of South Rustico, people who had too little land, too little money, and very little education, but ended up running what was probably the first people’s bank in North America, a precursor to today’s credit union.[21] Like most credit unions, we were started by a small group of people who wanted to help themselves. In 1943, 15 electric company employees formed a credit union where they could save their money and, most importantly, get access to loans when they needed them. In those days, there was no safety net when it came to unemployment insurance, social assistance, or medical care.[22] The strategic role of co-operatives is therefore to obtain goods and services and to meet the needs of a given region’s population in sectors where contributions by governments and private corporations are lacking. This is particularly the case in areas of activity where the government deems that private initiative is the best way to supply the goods and services demanded by the population but where conventional private businesses are not engaged because they foresee no commercial profitability. In these circumstances, co-operatives may be viewed as an alternative force for economic development. The case of gas co-ops in Alberta, which today manage more than 100,000 km of gas pipelines, is a striking example of a situation in which the co-operative movement has created wealth in an area of activity where private businesses were not involved because of the low profit potential of available projects. Over the past 50 years a spiderweb of low-pressure natural gas pipelines has been constructed throughout all inhabited parts of the province. Just about any Albertan has the ability to have natural gas piped directly into his or her home. Indeed, it is almost considered to be a right by Albertans. The reason Albertans enjoy this privilege is that 50 years ago this year a group of farmers south of Calgary got together around a kitchen table and decided to build the very first gas co-op. They were tired of natural gas companies saying it was uneconomical to build a pipeline to a farmer’s house.[23] The Co-operators Group, which now manages $42.9 billion in assets, was also founded to meet a community need that conventional private companies did not satisfy: Just as many cooperatives spring from unfulfilled social and economic needs, The Co-operators was formed by a group of farmers who sought insurance protection that the private capital market would not provide. Despite our humble beginnings, we are an excellent example of how the cooperative model is a thriving form of enterprise.[24] 3. A Stabilizing ForceOne of the main benefits of the co-operative model is its resilience to economic changes. In a recent study, the International Labour Organization noted that co-operatives around the world have shown a high degree of resilience to the recent financial crisis.[25] Similarly, a study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) states that credit co-operatives are more stable than commercial banks, as reflected by their less volatile returns.[26] The IMF study is interesting in that it was completed in January 2007, before the global financial crisis struck. Many witnesses told the Committee that the global financial crisis had proven beyond a doubt that credit co-operatives show greater financial stability internationally, as explained by the Desjardins Group and Co-op Atlantic: Cooperatives also enjoy greater stability because of their structure. They have a more loyal following and deeper roots in the community, but they have more trouble accessing capital quickly because they cannot issue shares. Therefore, they often maintain an extra cushion.[27] (...)one cannot overlook the fact that during the recent market financial crisis, cooperative shares did not lose any value, since they are owned locally by the people who use their products and services and have a long-term commitment to ensuring the success of the business endeavours.[28] The higher survival rate of co-operatives relative to conventional private businesses attests to the inherent resilience and stability of the co-operative sector. A study published by Quebec’s Department of Economic Development, Innovation and Export Trade in 2008 stated that the survival rate of co-operatives was higher than those of other forms of business. The survival rates of co-operative enterprises (excluding those in the housing sector) were 74.9% after 3 years, 62.0% after 5 years and 44.3% after 10 years. Survival rates for co-operative enterprises were higher than those of Quebec businesses as a whole, which were 48.2% after 3 years, 35.0% after 5 years and 19.5% after 10 years.[29] In Alberta, the survival rate of co-operatives after three years is 82% compared to 48% for other forms of business.[30] Many witnesses explained to the Committee that the very nature of co-operatives, that is to say the fact that they have roots in the community, a multi-criteria approach and long-term vision, are the reasons for that resiliency and greater stability. This was summed up by the Conseil canadien de la coopération et de la mutualité and the Conseil québécois de la coopération et de la mutualité: First of all, they are rooted in the community. Second, they answer the direct needs of the community. Third, they’re democratic, in the sense that it takes so much time to have a consensus among the people who want to start the cooperative that, when it’s done, it[‘s] not like a shooting star. These are, I think, the three major reasons why they last longer.[31] Coops also typically distribute their profits among their member-owners based on the size of their transactions, in other words, their transactional relationship, rather than the number of shares they hold. These differences make coops stronger: in periods of market fluctuation when the situation is not quite so rosy, coop members have a level of patience that shareholders subject to what we call quarterly tyranny do not. Every three months, shareholders can read about the company’s performance in the paper and check whether share prices have gone up or down, and capital levels respond in kind(…). coops are much more stable(…).[32] 4. A Force That Increases Market Efficiency: Competitiveness and CompetitionSince they pool individual resources, co-operatives make it possible to share knowledge and increase competitiveness. This pooling of resources is also the basis of a countervailing power that can be exercised against large organizations in a given market resulting in more competitive prices and service. Enhanced competitiveness can take various forms, including the supply of innovative goods and services. Those innovative goods and services can ultimately become the standard in a given market and increase the competitiveness of all players in that market. In the health care sector, the experience of the Health Connex co-operative in Nova Scotia illustrates the ability of co-operatives to provide innovative solutions through cooperation. The success of this kind of co-operative sector initiative could one day make this model indispensable, thus ultimately benefiting the Canadian population as a whole: HealthConnex — Connecting People for Health Cooperative is our business name — is a cooperative owned by cooperatives and credit unions in Nova Scotia. We’re owned by the people of Nova Scotia, and we are, as I indicated in my presentation, Canada’s first and only online health care clinic. We have created the technology, the functionality, the capacity, the ability for doctors and their patients to connect via the web — so our consumers, our subscribers, our patients in Nova Scotia, who are members of our clinic.[33] In addition to their potential impact on an industry’s competitiveness, co-operatives can improve the efficiency of markets through their effect on prices and markets for a given product. Two basic conditions must be met for a market to be considered efficient: first, the price must be determined by competitive forces and, second, there must be enough market outlets at that competitive price for corporate producers to sell their products. However, large oligopolies in certain markets can at times result in artificially high (or low) prices and/or extremely limited market outlets. Co-operatives may thus represent a countervailing power against large organizations and help establish a competitive relationship. This competitive balance will be characterized by more competitive prices and services and an increase in the number of market outlets. Consequently, the presence of co-operatives in a given market may at times be interpreted as a response to pre-existing deficiencies in that market. Their presence enhances the market’s efficiency, ultimately benefiting the community as a whole. Several witnesses referred to this strategic role of co-operatives in markets. The following excerpts from the brief submitted by the Institut de recherche et d’éducation pour les coopératives et les mutuelles of the Université de Sherbrooke and from the testimony of Credit Union Central of Canada. It is also important to note the market watchdog role that cooperatives and mutual organizations play. For example, the presence of funeral cooperatives in Quebec for nearly three decades has had and continues to have a regulating effect by lowering the price of funerals in Quebec by 50%. So, despite the competition and the presence of many traditional private companies, this economic sector, which was not optimizing the utilization of rare resources for the benefit of all, was transformed by the presence of cooperatives (currently about 20% of the market). These cooperatives ensure that all citizens have access to services at better prices. Similar dynamics are seen in the areas of housing, insurance, ambulance services and others. Tangible results have been achieved in a dynamic market through co-operation.[34] Credit unions, and cooperatives for that matter, were formed in the beginning because there were gaps in the market. Local communities felt they weren't getting the service they needed.[35] It should be noted that the pooling of resources and the exercise of a countervailing power making markets more competitive are not necessarily specific to the co-operative movement. Other types of organizations can produce similar results. However, those organizations are often based on co-operative principles: The way our organization is structured, with some co-op concepts, has ended up saving farmers hundreds of millions of dollars on the input side.[36] D. Financial Health of Co-operatives in Canada 1. Canadian Annual Survey of Non-Financial Co-operatives Having described the strategic importance of the co-operative movement for the Canadian economy in the previous section, we now examine some data on the current financial health of co-operatives in Canada. The Canadian Annual Survey of Non-Financial Co-operatives provides an overview of this issue. The survey describes the top 50 non-financial co-operatives in Canada by revenue. In 2010, the top 50 co-operatives had 38,700 employees and generated $24.8 billion in revenue. They represented 4.8 million members and managed assets of $10.9 billion.[37] Their average ratio of total debt to equity was 0.90.[38] The top 50 non-financial co-operatives consisted of 26 wholesale and retail businesses, 23 farming businesses and one service co-operative. The agricultural co-operatives posted the highest revenues ($12.8 billion), representing more than 51% of the total revenues of the co-operatives surveyed. The wholesale and retail co-operatives had revenues of $12 billion and accounted for 95% of all members. Mountain Equipment Co-op, a retail co-operative, has the largest number of members (3.4 million).[39] Figure 2 shows the increase in total revenues for the top 50 non-financial co-operatives in Canada. Except during the 2008‑2009 recession, revenues steadily increased between 2004 and 2010, as was the case for total assets, as shown in Figure 3. The data in Figure 3 show that co-operatives have managed to increase their assets while consolidating their financial position in recent years. Their debt-to-equity ratio declined from 2004 to 2010 (see Figure 3), indicating that the rise in assets resulted, above all, from an increase in equity, not an increase in indebtedness. Several witnesses referred to the good overall financial health of the Canadian co-operative sector: We are strong and we are stable. One out of every five cooperative enterprises fails. One out of three private sector businesses fails. (...) Cooperatives grew by 1.8% last year in Nova Scotia, despite the economic crisis. Our membership grew by 2%. Our top ten cooperatives paid a patronage dividend equal to 11% return on investment. I would suggest that’s a good place to put your money.[40] Figure 2 — Revenues of the Top 50 Non-financial Co-operatives in Canada Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from the Rural and Co-operatives Secretariat, Top 50 Non-Financial Co‑operatives in Canada, Annual Reports http://www.coop.gc.ca/COOP/display-afficher.do?id=1233009297681&lang=eng. Figure 3 — Assets and Total Debt/Equity Ratio of the Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from the Rural and Co-operatives Secretariat, Top 50 Non-Financial Co‑operatives in Canada, Annual Reports http://www.coop.gc.ca/COOP/display-afficher.do?id=1233009297681&lang=eng. 2. Financial co-operativesTable 1 shows the changes in various financial data of Canadian credit unions affiliated with Credit Union Central between the fourth quarter (Q4) of 2010 and Q4 2011.[41] It is important to note that the other major credit union federation in Canada, the Mouvement des caisses Desjardins (Mouvement Desjardins), is not affiliated with Credit Union Central. The Mouvement Desjardins’ financial information is therefore not reflected in Table 1. The assets of credit unions affiliated with Credit Union Central

increased by 10.1% from the end of 2010 to the end of 2011. Deposits at credit

unions rose 7.4%, while loans in circulation granted by those organizations

increased by 9.9%. The number of locations remained relatively stable (-0.1%),

but the number of credit unions declined by 4.7%. Table 1 — Changes in Various Financial Data of Credit

Unions Affiliated with Credit Union Central

Source: Table prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Credit Union Central of Canada, System Results, 4th Quarter 2011 http://infocentre.cucbc.com/_html/pdf/4Q11SystemResults.pdf. Table 2 shows changes in various financial data of the Mouvement Desjardins between Q4 2010 and Q4 2011. Assets, deposits and loans grew by 6.0%, 7.4% and 6.5%, respectively. The number of caisses (locations) and the number of members declined respectively by 6.4% and 1.9%. The same trend in changes in the number of members and locations was observed between 2009 and 2010. Table 2 – Changes in Various Financial Data of the

Mouvement Desjardins between Q4 2010 and Q4 2011

Source: Table prepared by the Library of Parliament using

data obtained from Credit Union Central of Canada, System Results, 4th Quarter

2011 http://infocentre.cucbc.com/_html/ pdf/4Q11SystemResults.pdf and Desjardins Group, ʺManagement’s

Discussion and Analysis of Desjardins Groupʺ, in Annual Report 2011 These figures show solid growth in Canadian credit unions’ assets, deposits and loans over the past two years, as well as consolidation among those institutions through acquisitions and mergers. This growth, together with workforce consolidation, is in fact part of a strong trend observed in the credit co-operatives sector in recent years. Several witnesses commented on these developments in the credit union sector in Canada. The following gives an overview of their testimonies. Credit unions continue to be strong performers. Even through the economic crisis, Canada’s credit union system performed extremely well and our credit unions continue to be positioned as world class financial institutions (...). The strong financial performance has resulted in continued growth in membership. Consolidation in the credit union system is a continuing trend. For decades, some credit unions responded to increased complexity compliance costs, and changing demographic through consolidation.[42] Over the past decade, the size of the average credit union's balance sheet has tripled. Not only is the average credit union growing, but the largest credit unions make up a significant share of the credit union system in some provinces. In Alberta, the two largest credit unions make up 73% of the credit union assets in the province, and the largest institution accounts for 58% of assets. In British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Ontario, the figures are 51%, 40%, and 37% respectively for the two largest institutions.[43] CHAPTER II — FINANCIAL ISSUES RELATED TO CO-OPERATIVES IN CANADAA. Government Intervention in the Co-operative Sector1. Rural and Co-operatives SecretariatThe Rural and Co-operatives Secretariat (RCS), which is under the jurisdiction of Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada (AAFC), coordinates the co-operative development work of the Government of Canada. A number of witnesses acknowledged the good work that RCS has done since it was established, and AAFC representatives were in agreement about RCS’s accomplishments: There is no question that the rural and cooperatives secretariat has laid solid groundwork for communities to more effectively interact and take advantage of opportunities that exist to advance their interests.[44] However, many witnesses were afraid that the role of the RCS might become less important as a result of budget cuts, and some were concerned that staff cuts at RCS might result in fewer services being provided. Witnesses also feared it would be difficult to access statistics on co-operatives, data that are an invaluable source of information for the co-operative movement: The fact that all the secretariat’s resources have been cut significantly has repercussions. In particular, the statistics we used to rely on in order to understand the big picture and the state of Canada’s cooperative movement will virtually disappear.[45] Although RCS has been hit by budget cuts, AAFC representatives stated that RCS will continue to play an important role in the co-operative sector and gave reassurances that its database would be maintained: We reduced the role of the Rural and Cooperatives Secretariat to bring its role back to what it was previously, which was research and policy coordination with the provinces and other departments. We did that with the goal of working with those departments and ensuring that they explore the various avenues with the rural regions and the cooperatives. The main function of the secretariat when it comes to cooperatives will be to maintain the database on cooperatives, which has existed now for several decades. That is one need of the cooperatives sector. It assures us that this sector will continue to be healthy.[46] As noted above, RCS is under AAFC’s jurisdiction. Several witnesses, including the Coop fédérée, emphasized that it was now inappropriate for RCS to be under AAFC’s aegis since co-operatives no longer have a solely rural or agricultural purpose: (…) historically, the Canadian government has put the department of agriculture in charge of cooperatives. One hundred years ago, the country’s development actually went through the agri-food industry. The Fathers of Confederation felt that cooperatives were part of the agricultural industry. That was logical then. However, in 2012, issues related to energy cooperatives have little to do with the department of agriculture. The reality has changed along with the era.[47] For that reason, many witnesses, including Tom Webb, Adjunct Professor, Saint Mary’s University, and the Conseil canadien de la coopération et de la mutualité suggested that RCS be transferred to Industry Canada. I’m hoping we will see a refocusing, perhaps in the Department of Industry, which may have been in some ways a more appropriate home, but there needs to be a home somewhere for a focus on cooperatives in the federal government.[48] Transfer the statistical data compiled by the Rural and Co-operatives Secretariat to Industry Canada. [49] 2. Programsa. Co-operative Development InitiativeThe Co-operative Development Initiative (CDI) is a program that the federal government established in 2003 to assist with developing a co-operative. The initiative is divided into three components: advisory services, research and knowledge development, and innovative co-operative projects.[50] CDI will expire in March 2013 following two five-year terms and will not be renewed. A number of witnesses noted that the CDI program has proven to be a very useful tool over the years as it is one of the rare sources of funding to assist in starting up co-operatives. According to these witnesses, CDI has been a resounding success in the co-operative sector since its inception. This was particularly the case for Arctic co-operatives, as pointed out by Andy Morrison, Chief Executive Officer, Arctic Co-operatives Limited: So the efforts of the CDI program have enabled us to use our expertise to work with primarily aboriginal communities, which I think has been very beneficial.[51] As a result of this success, witnesses were critical of the fact that the CDI program is not being renewed but said they understood that government programs are subject to periodic review. Those witnesses remained very much open to the idea of new government initiatives to support the co-operative sector. One AAFC representative put the non-renewal of CDI in context: The programs of the rural and cooperative secretariat have achieved their objectives, and like many of the programs in other departments, they have not been renewed. There is no question that the rural and cooperatives secretariat has laid solid groundwork for communities to more effectively interact and take advantage of opportunities that exist to advance their interests. That said, we believe that virtually every department of government has a responsibility for rural development, particularly economic development. Every department needs to ensure that its programs and policies reflect the unique circumstances of rural Canadians.[52] b. Other ProgramsCDI is no doubt the most widely known federal program in the co-operative sector. However, a broad range of programs intended for small and medium-sized enterprises is also available to co-operatives. The problem is that co-operatives are not always aware of the range of government initiatives available to them. Consequently, the federal, provincial and territorial departments have prepared a guide to inform co-operatives about accessible co-operative programs: We have realized that cooperatives did not know that they could register for several of these programs. We distributed a copy of our guide to all the cooperatives just so they would know that they are eligible for these programs.[53] Some programs are intended for co-operatives based on their area of activity. The Canada Small Business Financing Program and the Canada Business Program provide assistance to small businesses,[54] and housing co-operatives have access to various funding programs through Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC).[55] Many programs are available to co-operatives in the agricultural sector, particularly the Loan Guarantee Program, under which agricultural co-operatives may obtain loans of up to $3 million: One example is the Canadian Agricultural Loans Act, a financial loan guarantee program that gives cooperatives easier access to credit. Under CALA, agricultural cooperatives can access loans of up to $3 million to process, distribute or market farm products.[56] B. SPECIFIC ISSUES1. Housing Co-operativesMost housing co-operatives in Canada have been established to meet the need for affordable housing for low-income earners. In the 1970s, three federal programs promoted the development of housing co-operatives. Currently, many housing co-operatives receive Canadian government funding through the CMHC. CMHC, which reports to Parliament through the Minister of Human Resources and Skills Development, plays a major role in the mortgage credit sector. Witnesses from housing co-operatives shared their concerns with the Committee regarding what they consider early repayment penalties assessed by CMHC for refinancing or loan consolidation purposes: Usually a private lender, if you wanted to break the first mortgage and refinance it, would charge you something like a penalty of three months interest. CMHC have taken the position that a co-op exiting its first mortgage will pay a penalty equal to the entire interest that would have been paid on the mortgage, even though the mortgage no longer exists.[57] I’m not suggesting that the co-op should not pay any penalty. Obviously, there’s a transition cost for CMHC. It would take a while to do this. We’re willing to contemplate a reasonable penalty. Mortgage holders in the private sector do this all the time, right? It’s not a new idea. But we think that the full burden of the interest until the rollover to the next term is simply excessive, and it’s a barrier to preserving affordable housing in Canada.[58] In response to questions from the Committee concerning the early repayment penalties imposed by CMHC, the Corporation has issued a news release stating that a co-operative may refinance its mortgage with a private lender at the time of mortgage renewal with no penalty. However, where a mortgage contract is broken, a penalty is assessed based on the terms and conditions of the mortgage contract, the mortgage amount, the interest rate and the time remaining to mortgage maturity.[59] CMHC also notes that any mortgage restructuring may also entail costs: To provide the lowest interest rates possible, CMHC locks in its funding cost at the same time as it lends to project sponsors. As such, any restructuring of the mortgage has the potential to cause a loss to CMHC since the Corporation cannot restructure the underlying debt.[60] 2. Taxationa. Income TaxCo-operatives are subject to the same taxation regime as any other corporations. The federal Income Tax Act provides for special measures to assist small businesses, such as accelerated capital depreciation and lower corporate tax rates. Those measures also extend to co-operatives. Credit Union Central noted in a written brief to the Committee that banks suggest credit unions enjoy advantageous tax rules as a result of their co-operative structure.[61] In response to that assertion, Credit Union Central stated that co-operatives pay as much tax as other types of businesses. Other witnesses agreed, noting that co-operatives enjoy no special tax treatment and are subject to the same tax rules as other businesses: The Income Tax Act does not favour cooperatives over other types of corporations. Whether you are a wheat pool, a dairy co-op, a retail co-op or a co-op wholesaler — all pay income tax at the same rates and with the same rules.[62] Some witnesses stated that co-operatives are taxed more than business corporations. In one study, the Mallette firm found that there is a significant disparity in the taxation of co-operatives and conventional businesses. The study shows that most co-operatives bear a greater tax burden than business corporations. Some witnesses suggested that the Canadian tax system penalizes co-operatives because they are subject to “double taxation”. However, large co-operatives have resources that enable them to structure their businesses so as to avoid double taxation. A report by Ernst and Young explains this form of double taxation in detail. In taxation matters, there is one tax issue that concerns private as opposed to public organizations. According to the United Farmers of Alberta, it is unclear to what class of business co-operatives belong: Co-ops are neither public nor private, by definition, and there are certain exemptions that take place. Really what we’re talking about there is that certain parts of the tax act are applicable or exempt, and the waters are really quite murky. What we’re really talking about there is simply calling it out as a distinct business model and taking out the ambiguity. Where that ambiguity exists today actually creates opportunities for us to misinterpret or be offside, totally unintentionally. The other thing it does, with that simple clarification in the act, if it were to take place, is actually raise the awareness and the relevance of the cooperative business model, right there in that one singular thing. That is without changing anything within what is contemplated by the tax act as it exists today. So it does remove ambiguities, and it creates clarity for us.[63] b. Registered Retirement Savings Plans (RRSP)Several witnesses noted that the Canada Revenue Agency’s RRSP rules do not encourage investment in the co-operative sector. The so-called “10% rule” prevents the members of certain co-operatives from using their RRSPs as investment vehicles to recapitalize their co-operatives: The measures regarding self-directed RSPs in the 2011 budget have rendered co-op shares ineligible for RSPs for members who hold more than 10% of any class of shares issued by the cooperative. This has eliminated a pool of members’ capital that used to be available to help capitalize their co-ops. Many worker co-ops have fewer than 10 members. Whereas it used to be perfectly fine to hold more than 10% of a class of shares in a co-op within an RSP, if under $25,000, it is no longer acceptable. If an individual is affected, there are very high penalty taxes — even higher than for deliberate fraud in some cases. We believe these provisions are putting jobs at risk. CWCF objected strongly last summer to the Ministry of Finance regarding these changes, as did CCA, CCCM, the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants, and the Canadian Bar Association. We implore the federal government to revoke these measures enacted in the 2011 federal budget.[64] The members of certain co-operatives therefore feel an obligation to use their RRSPs to invest in business corporations, even though their first choice would be to invest in their co-operatives. This exacerbates the problem of co-operative capitalization. Some witnesses therefore requested that the 10% rule be repealed in the case of co-operatives. Some provinces have put tax measures in place to support the co-operative sector. Quebec was often cited as an example of a province that provides an important support to its co-operative sector. Under the Régime d’investissement coopératif (RIC) in Quebec, members and employees of producer or worker co-operatives who invest in co-operatives receive a tax credit. Nova Scotia has created a similar support mechanism, which encourages the capitalization of co-operatives: We have a community investment tax credit where we can invest in community projects, cooperatives, and private business projects and get tax credits, a 35% provincial tax credit. It’s RRSP-eligible.[65] The Alberta Association of Co-operative Seed Cleaning Plants also suggested that the tax rules should be amended to facilitate investment in co-operatives: At our 2010 annual general meeting, we passed a resolution that the provincial board would lobby for refundable investment tax credits and RRSP investment status for agriculture investors who invest in co-ops. This would allow co-ops to raise the required capital to acquire depreciable assets. The existence of such a tax credit would give members and other agriculture investors benefits comparable to other Canadian investments.[66] In short, to encourage investment in the co-operative sector, a number of witnesses proposed an amendment to the Income Tax Act to allow more than 10% of the shares of a co-operative to be held in the RRSP of a single individual. In addition, federal or provincial plans similar to Quebec’s RIC could prove to be a useful tool in financing co-operatives. This is supported by the following excerpts from testimony: We would also look favourably upon the federal government’s creation of a program based on the example of Quebec’s Cooperative Investment Plan. Programs of that kind, which do not come at high cost to the government, favour the capitalization of cooperatives by encouraging members to be disciplined or patient, and to reinvest in their cooperatives.[67] As a small workers' co-operative we feel we can no longer have use self-directed RRSPs to support our co-operative, because if two member left the co-operative our members would hold more than 10% of the shares issued by the co-operative.[68] 3. Competition from Farm Credit Canada in the Agricultural Loans MarketThe issue of competition from Farm Credit Canada (FCC) was raised many times in the meetings and in the written briefs the credit unions sent to the Committee. FCC is a commercial Crown corporation (i.e. a for-profit entity) that offers financing solutions exclusively to businesses operating in the agricultural sector, which includes co-operatives in particular: Our sole focus is agriculture. We lend to agriculture in all sectors, in all geographic regions, and to all sizes of operations and business models. Our mandate is to ensure that the agriculture industry has ready access to capital to withstand the unique challenges and opportunities facing producers over the long term, through good times and challenging times.(…) Many of our customers are cooperatives, and they represent an important part of our lending program. The cooperatives we work with operate in most of the agricultural sectors, including crop inputs, beef, dairy, and agrifood.[69] Unlike the Canada Business Development Bank (BDC) and Export Development Canada (EDC), whose financing operations complement those of private financial institutions, FCC competes directly with credit unions in the agricultural lending field. However, according to the credit unions, FCC’s status as a Crown corporation gives it definite advantages in that area: Credit unions value the role of Farm Credit Canada, the role it plays as a committed partner that supports Canadian agriculture in good times and bad. However, the FCC is in an anomalous position relative to other crown financial institutions. It does not face a requirement to lend in the manner that complements the activities of private sector FIs, but instead it can aggressively compete head to head with credit unions while enjoying marked advantages that are related to its status as a crown corporation.[70] One of the issues related to competition is FCC’s ability to borrow at the Government of Canada’s interest rate (which is the risk-free benchmark rate in financial markets), which other financial institutions cannot do. FCC admitted this fact but downplayed that analysis, pointing out that the rates it offers its clientele are comparable to those of other financial institutions: We borrow money through the consolidated revenue fund, and that’s at a good price, for sure. But banks have a double-A rating, and they’re able to access funds at an attractive price as well. Plus, they have millions of dollars of deposits on hand. They pay very little interest, and they can use that to reinvest in their lending program. All that being said, every time we’re making a price adjustment, where there’s a competitor involved, we do not undercut the competition on price. We believe that by winning the business based on service and knowledge, we compete very fairly in the marketplace.[71] According to a brief the Credit Union Central of Canada sent to the Committee, the advantages FCC enjoys as a result of its status as a Crown corporation are not limited to an enviable borrowing rate. FCC pays no income tax and is subject to minimum regulatory supervision.[72] Again according to Credit Union Central of Canada, FCC has captured nearly one-third of the agricultural loans market, twice the market share it held in 1993. Furthermore, FCC’s returns on equity are appreciably higher than those of BDC, which raises the question whether this kind of performance is compatible with FCC’s status as a Crown corporation with a clear public policy mandate.[73] Credit Union Central of Canada therefore asked that FCC be subject to regular parliamentary review of its mandate, as is the case with BDC and EDC, and that the government consider amending its operating principle: It is also unique in that unlike Export Development Canada and the Business Development Bank of Canada, FCC is not subject to a regular parliamentary mandate review. Canadian Central recommends that the government undertake a public review of the Farm Credit Canada Act to ensure that FCC continues to play a relevant role in a competitive marketplace. We also recommend that the government consider amending FCCs legislation and operating principles to bring them into closer alignment with those of the Business Development Bank and Export Development Canada.[74] CHAPTER III — THE ISSUE OF CAPITALIZATION OF CO-OPERATIVESA. Capitalization: Definition and BackgroundCapitalization may be defined most simply as the act of “raising money”.[75] In the financial sector, capitalization can be defined as : The amounts and types of long-term financing used by a firm. Types of financing include common stock, preferred stock, retained earnings, and long-term debt. A firm with capitalization including little or no long-term debt is considered to be financed very conservatively. [76] First of all, it should be noted that financial capital is not scarce as such; access to capital by one business does not result in a scarcity of capital for other businesses. In that sense, the amount of financial capital available is unlimited. What makes access to capital difficult for a given business is in fact the risk of default, or rather the way in which this risk is perceived by financial institutions and investors. If default occurs, the financial institution concerned may not recover its money and will have to incur a loss on its loan: At the end of the day, it’s easy to give money away. It’s really, really hard to get it back. No financial institution wants to realize on security.[77] The risk assessment of a given business endeavour by a financial institution is based on three main factors: capacity to repay, collateral security and the quality of managers: The role of any lender is to assess the risk associated with a financing request, taking into account the strength of the cooperative’s management and governance, the capacity to repay, as well as the adequacy of collateral security.[78] Consequently, the level of risk explains why financial capital is often perceived as “scarce”. The greater the perceived risk of default, the more difficult it is to access financial capital. In the case of loans, this increased risk often results in higher interest rates. If the perceived risk is very high for a particular business, then access to financial capital for this business will be very difficult, perhaps impossible. This relationship between risk assessment and access to capital is valid for every type of business, both co-operative and non-co-operative: The fundamentals of lending and credit risk are really no different for a co-op and a non-co-op.[79] This background information is important in addressing the issue of capitalization of co-operatives. Any examination of the causes of reduced access to capital must focus on factors that might be at the root of the perception of higher risk in the case of co-operative enterprises. Witnesses commented at length on these factors, which may be classified as institutional (i.e., stemming from a lack of understanding by institutions of the nature of the co-operative business model) or structural (i.e., related to the very structure of co-operatives). As shown below, the institutional factor is a stumbling block for all types of co-operatives, whereas the structural factor is mainly an obstacle for start-up co-operatives. B. Institutional Obstacle: Lack of Knowledge of the Co-operative Business ModelOne factor that witnesses frequently cited at Committee meetings to explain why access to financial capital may be tougher for co-operatives is public and private institutions’ lack of knowledge of the co-operative business model. Witnesses indicated that this lack of knowledge has a direct impact on financial institutions’ risk assessment of any given project in the co-operative sector and thus on access to financing: There seems to be such ambiguity about the decision-making process and how decisions are made within co-ops that traditional banks or lenders, and even some statutory government boards, such as the BDC, because of their unfamiliarity with the decision-making process, may feel that there is more risk attached to it.[80] Some witnesses stated that federal institutions’ lack of knowledge of the co-operative system has a direct impact on access to government funding: Some of the main issues that impede cooperatives from accessing federal funding and programs are a lack of understanding among government staff as to what a co-op is. Most don’t see it as a serious business model. In its language, current federal programming refers to corporations, partnerships, sole proprietorships, and not-for-profits, but rarely cooperatives.[81] Many of our people in government departments have no idea what a cooperative is or how it works or how it could be a successful business model. That’s part of the challenge.[82] Witnesses felt that this criticism also applies to private institutions and that their lack of knowledge of the co-operative business model constitutes a barrier to financing for all types of co-operatives, large and small. For example, Michael Barrett, who is the chief operations officer of a co-operative with assets of $230 million and virtually no debt, told the Committee that this problem also affected his co-operative: The opposite side of that is that the banks don’t understand cooperatives and don’t understand what it means to have members investing in them, and therefore they are very reticent, suspicious, and reluctant to do what I would say is a normal business loan case. So we have a bit of an issue with that.[83] Some witnesses went into greater detail about financial institutions’ lack of understanding of the co-operative business model. They explained that much of the problem stems from the fact that those institutions do not understand the co-operative ownership structure. In particular, financial institutions tend to treat members’ investment in their co-operative as a debt owed by co-operatives because it may be returned to a member when he or she ultimately leaves the co-operative: The issue we constantly have is the differentiation between members’ investment. Banks will see that as debt, and it’s not debt; it is equity, because it is generational capital that doesn’t leave the cooperative. When they calculate how much money they will loan you, it is always based upon members’ investments being debt.[84] Many witnesses told the Committee that credit unions are more likely to understand the co-operative ownership model. Financial co-operatives explained that they can arrange syndicated or aggregated loans in order to meet the larger needs of their members. One witness noted that the assistance of credit unions had been critically important to his co-operative: Certainly we’ve had tremendous help from our credit union system in general. We certainly would not be in business today if it wasn’t for the support of our credit unions on P.E.I. They’ve done a tremendous job keeping us in business. To be perfectly honest with you, with the margins that we’ve made and the difficulties that the industry in general has had over the last three or four years, if we were dealing with a regular bank, our 57 years would probably have ended within the last few years.[85] Given their size, however, individual credit unions are not always potential lenders in all situations, as in the case of the Gay Lea Foods situation cited below: (...) we had to go to the bank to borrow that, with great difficulty and by putting a greater number of my assets up as a lien, which no other organization would have been forced to do. But because they didn’t understand the model, I had to put up a lot of my assets as security for that loan. I am glad to say that we paid that loan off in four and a half years, to make sure the banks didn’t get as much interest as they deserved.[86] It is also difficult to estimate accurately the extent to which this greater understanding of the co-operative business model has an impact on risk assessment: One thing I can say is that they would understand the cooperative principles and the governance principles. I don’t know how that weighs in their factors in looking at risk and a possible default on a loan, but they would understand it.[87] One witness, however, stated that the lack of knowledge of the co-operative system and the resulting difficulty in obtaining financing was a criticism that applied to some credit unions as well. That witness did, however, single out and praise Farm Credit Canada’s work with agricultural co-operatives: It’s mostly the financial side and the capitalization side of the funding of co-ops. And it is in the credit unions as well as on the traditional banking side. To give Farm Credit their due, Farm Credit is probably one of the stronger ones. Certainly in Atlantic Canada, in my experience, they’ve been very good at recognizing cooperative lending, and they understand it. I think it’s fair to say that Farm Credit probably has been very good if you fit into their agricultural model. If you’re into housing cooperatives or into consumer cooperatives, then of course Farm Credit doesn’t lend to them, so there is a gap there.[88] C. Structural Barriers to Obtaining Financial Capital: Start-up Co-operatives1. Venture Capital: Introduction and BackgroundAs one witness pointed out, a key feature of financial capital is its ability, when well managed, to grow, thus creating added value: We had an initial capital injection from various levels of government in 1986, and we have grown that. Initially, it was $10.2 million in capital; to the end of 2011, we have provided financing of more than $525 million to cooperatives across the Arctic since 1986.[89] That value added, in the form of self-generated funds, will eventually enable an enterprise to become less reliant on outside capital and thus to reduce its risk profile. However, the essential ingredient in this process of growing financial capital is “seed capital”. It is important to note here that the seed capital market (also called the venture capital market) is a highly specialized segment of the financial markets. As one witness noted, given the inherent risks of the venture capital market, the process of allocating seed financing is not for the fainthearted. In fact, according to the witness, regulators do not always take a favourable view of a conventional financial institution that engages extensively in this specialized market because of the risk profile associated with it.[90] As a result, traditional financial institutions are generally reluctant to grant venture capital, although this does not mean they are completely absent from this market. Some credit unions stated that their institutions do allocate funding to venture capital financing: In terms of spinoff, Desjardins Group offers businesses venture capital.[91] We also provide microcredit for business start-ups that would otherwise not qualify for conventional financing.[92] In general, however, the allocation of venture capital in the financial markets is mainly the prerogative of specialized players in that field, both private and public (the Business Development Bank of Canada, for example, is a player in the Canadian venture capital market). The modus operandi of those players (sometimes called angel investors) is often to become significant shareholders in a start-up business by acquiring a portion of its share capital. Thus, if the start-up is successful, the angel investors’ reward (i.e. their return on invested capital) could be considerable. The potentially attractive rate of return on invested capital makes the involvement of angel investors possible since it offsets the very high risks associated with this type of investment. 2. Raising Venture Capital for Co-operativesAs noted in the last section, a lack of knowledge of the co-operative ownership model may affect financial institutions’ risk assessment of co-operatives, thus tightening access to credit for the latter. For large co-operatives, as the example of Gay Lea Foods illustrates, the impact of this lack of knowledge on risk assessment can be offset by providing more collateral to financial institutions. That is not an option for start-up co-operatives, thus making the problem of access to capital even more acute for them: That’s why I think you’re seeing that cooperatives that are older and traditional and have been around for a while are quite strong. It’s the young ones that have the problems. The young ones are having trouble trying to find capitalization to get going and/or getting enough money up ahead to be able to grow their business.[93] Obtaining seed capital is in fact a major challenge for all types of businesses, not just co-operatives, but it is an even greater problem for co-operatives as a result of certain specific characteristics of the co-operative ownership model. First of all, it is generally not possible for an outside investor to inject seed capital into a co-operative by acquiring and owning its share capital. The impossibility of both attaining the kind of capital growth that would occur in a conventional private business and realizing substantial capital gains by selling shares on the market makes co-operatives unattractive to angel investors: The fact that cooperatives are owned by their members and that their shares cannot be traded, as with private corporations, is a critical issue in capitalizing coops. The cooperative business model with its “one member, one vote” principle promotes the ownership and control of cooperative businesses. Members, rather than outside investors, hold coop shares. Coops also typically distribute their profits among their member-owners based on the size of their transactions, in other words, their transactional relationship, rather than the number of shares they hold.[94] Investing seed capital in a co-operative by holding its preferred shares or debt could be an alternative. However, this approach may place an excessive interest rate burden on a start-up co-operative as a result of its very high-risk profile, unless it can find a way to provide collateral. As noted above, however, a start-up co-operative typically has very few assets to pledge as security and must therefore rely on contributions from founding members. As those members may be numerous, and all hold an equal ownership share in the co-operative, it is difficult for them to put up a large percentage of their tangible property as collateral in order to start up a business in which they are very much minority partners. A splitting of assets pledged as collateral is an option, but that approach is not always possible. This kind of problem does not arise to the same degree for conventional private businesses, in which ownership is concentrated in the hands of a single individual or entity. Several witnesses touched on one or more aspects of the capitalization of start-up co-operatives addressed in this section. These aspects can be summed up by the following two excerpts from testimony: Small cooperatives, of course, have the challenge of acquiring a small amount of financing in the beginning, because they can’t always use their equity or property as a traditional business would.[95] In seeking capitalization, emerging cooperatives have two barriers that conventional corporations do not face. First, the democratic structure of one member, one vote, and the limited returns on capital mitigate against the usual sources of venture capital, which require high returns and significant control of the enterprise. Second, because co-op par value shares do not generate capital gains, members do not receive the same tax incentive from the government to reinvest in their enterprises.(…) From the straight getting of a loan, the process is somewhat the same when the institution looks at the financials. One of the differences comes down to the fact that they’re actually collective entrepreneurships, but bankers and credit union managers as well — indeed, this happens in the credit union system as well —are used to dealing with one individual who will put a personal guarantee and sign off their house to take that risk. They are not used to dealing with a collective group of 5 or 10 people, with a start-up.[96] CHAPTER IV —REGULATIONS AND OTHER ISSUES CONCERNING CO-OPERATIVES IN CANADAA number of legal issues were raised in Committee meetings as well as in written briefs. The sections below provide an overview of these issues. A. Federal credit unions and recommendation of the Red Tape Reduction CommissionSeveral credit union representatives praised the Government of Canada’s initiative to legislate the creation of federal credit unions. The main advantage for credit unions to be incorporated under federal law is that they can be active in several provinces outside their home province,[97] which helps the credit unions achieve their business goals and improve services to members.[98] However, these witnesses urged federal authorities to tailor the regulations accompanying the new legislation to the structure and size of co-operatives: Our hope is that the federal government will continue to honour the governance structure of these credit unions, and ensure that the rules respect the co-operative principles that laid the groundwork for the creation of these credit unions. If credit unions are simply considered and treated as “banks”, then the stability and resilience of the credit union structure may be lost, along with the co-operative values and social responsibility they represent.[99] Many witnesses from the credit union sector echoed the report of the Red Tape Reduction Commission, which noted that a one-size-fits-all approach to regulation tends to impose an undue burden on smaller businesses like credit unions.[100] The Commission’s recommendation (No. 13) on reducing red tape to which these witnesses refer is presented below: Government should move quickly to fulfill its Budget 2011 commitment to implement a small business lens. While constructing, consideration should be given to requiring that regulators make publicly available the results of having applied the small business lens to new or amended regulations.[101] Credit unions have therefore requested that the principle set out in this recommendation be met when the regulations on credit unions are made. Credit unions have indicated that they do not expect preferential treatment; they simply expect that a small business lens be used by financial authorities rather than a uniform approach: We’re not looking for special rules; we’re simply looking for the small-business lens that was promised in the Red Tape Reduction Commission.[102] Witnesses also provided concrete examples of regulations that impose or may impose an excessive burden if they do not take into account the structure and size of credit unions. These examples relate particularly to the new law mentioned previously, the requirements of the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC), accounting rules, regulations concerning the release of financial prospectuses, the requirements of the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (CDIC) and the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada (OSFI). The Credit Union Central of Canada painted a clear picture of the situation faced by small credit unions: I could use the example of Surrey Credit Union(...). It has 10 or 12 employees and has the same requirement as VanCity in Vancouver or the Royal Bank of Canada when meeting those FINTRAC requirements. This has a disproportionate effect on the administrative costs in that credit union. As far as the burden we work under is concerned, that would be the challenge we face.[103] B. DemutualizationMutual companies are founded by individuals who band together to protect themselves against certain risks. In exchange for this protection, members pay a premium. A mutual company therefore belongs to its policyholders.[104] Over the last decade, there has been a trend toward demutualization in the life insurance sector.[105] Demutualization is the process by which a mutual company is converted into a stock company. According to Desjardins Group, four situations can lead to demutualization:[106]