JUST Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

INTRODUCTIONOn February 9, 2009, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights (the Committee) adopted the following motion: Pursuant to Standing Order 108(2), it is moved that the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights devote four sittings to the study of the state of organized crime in Canada and the consequential legislative amendments that should be made and that the Chair report its conclusions and recommendations to the House. The Committee quickly realized that many more meetings than those discussed in the motion would be required in order for it to acquire some understanding of the state of organized crime for three main reasons. One was that the witnesses who testified before the Committee made it clear that the term “organized crime” covered a wide array of criminal activities that affected many facets of Canadian society. Its effects can be felt not only in the criminal justice system, but also in the areas of education and social services, to name but a few. To explore properly the effects of organized crime and the legislative means of tackling it would take many more meetings than originally scheduled. The second main reason to have more meetings on organized crime was that the issues raised were not only large in number, but complex in nature. One example of this was the issue of crime prevention versus crime deterrence. Different witnesses had different perspectives on this topic, depending upon their background. The Committee chose to hear from a diverse range of witnesses, including law enforcement officials, victims of crime, workers with social service agencies, academics, journalists, business people, government officials, and members of the public. Out of this diverse group of witnesses, the Committee was presented with a wide range of opinions on the many issues addressed in this report. The third main reason that more meetings would be required to carry out this study was that no single definition of “organized crime” can be applied across Canada. In such a diverse country of regions, it is perhaps not surprising that organized crime takes on many and different forms in different parts of Canada. As a result, a legislative solution that may work in one area may prove to be less effective in another. The Committee, therefore, felt it was important to explore as many different parts of Canada as budgets and time allowed in order to investigate the nature of organized crime at the local level. The Committee was left with difficult decisions as to where to travel as part of its study. In the end, it has heard witnesses in Ottawa, travelled to Vancouver, Montréal, Halifax, Toronto, Edmonton, and Winnipeg for public hearings, and received briefs from various individuals and organizations.[1] While it was not possible to visit every community that members of the Committee wished to, it was felt that the cities chosen provided some representation of the diversity of organized crime activities in Canada. In addition to its organized crime study, the Committee has also heard related testimony on Bill C-14, an Act to amend the Criminal Code (organized crime and protection of justice system participants)[2] and as part of a study on declaring certain groups to be criminal organizations.[3] The Committee also benefited from testimony on the issue of “gangsterism” heard during the 1st Session of the 39th Parliament.[4] THE NATURE OF THE PROBLEMOrganized crime poses a serious long-term threat to Canada’s institutions, society, economy, and to our individual quality of life. Many organized crime groups use or exploit the legitimate economy to some degree by insulating their activities, laundering proceeds of crime and committing financial crimes via a legitimate front. Organized crime groups exploit opportunities around the country and create a sophisticated trans-national network to facilitate criminal activities and challenge law enforcement efforts. The Committee was informed that gangs and organized crime have been with us for at least 150 years. Alienated and disenfranchised young men long ago forged a common bond of lawlessness, using crime as a means of generating wealth. New opportunities for organized crime arrived when illicit drugs became more widely available, due to the increasing ease of international travel and commerce.[5] Organized crime involves white collar criminal activity, gang activity and both domestic and foreign participants. Organized crime is of concern not only for its direct impacts, such as the selling of illicit drugs, but also for the indirect impacts, such as the violence that spills into the larger community when rival organized crime groups try to gain control over areas in which to sell drugs. There are immediate and direct costs to the victims of organized crime. These costs can be financial but, more importantly, they can be physical in nature as well as mentally and emotionally traumatic. The losses suffered by victims through such things as the violation of their sense of personal safety and security are long-lasting and difficult to measure. Victims of organized crime can be found everywhere as this type of crime knows no boundaries and carries out its activities in communities of all sizes. Such activities can occur everywhere through such things as fraud over the Internet, the sale of counterfeit goods, and breach of intellectual property laws. The cost of crime is not only a personal one, however, as it is passed on from victims to their insurance companies to businesses and then to consumers. In this way, the personal toll of organized crime becomes a burden on society as a whole. Furthermore, there is also a high price for taxpayers in the form of increased costs for law enforcement and the justice and correctional systems. Domestic policing efforts across Canada increasingly require the development of strategies and programs that address the international components of organized crime. Currently, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and local law enforcement units are focused on reducing the threat and impact of organized crime. In countering the growth of organized crime groups and dismantling their structures and sub-groups, a critical component is the improved coordination, sharing and use of criminal intelligence and resources. This sharing of information and resources is used in support of integrated policing, law enforcement plans and strategies, and assists the police in communicating the impact and scope of organized crime. The impact of organized crime on the lives of Canadians was certainly communicated clearly to the Committee throughout its hearings. The Committee also heard a level of frustration with how the justice system functions in this regard. There was often an expressed perception that this system operates with a bias in favour of the accused rather than the victim.[6] LAWS IN RELATION TO ORGANIZED CRIMEThe offence of participation in a criminal organization was enacted in 1997 as part of Bill C-95.[7] At that time, a “criminal organization” meant any group, association or other body consisting of five or more persons, whether formally or informally organized, that met two requirements: (1) have as one of its primary activities the commission of an indictable offence under this or any other Act of Parliament for which the maximum punishment is imprisonment for five years or more; and (2) any or all of its members engage in, or have, within the preceding five years, engaged in the commission of a series of such offences. That offence was punishable by a term of imprisonment not exceeding 14 years, and required that the accused have participated in the activities of a gang and been a party to the commission of an indictable offence committed in relation to a criminal group. Coming into force in 2000, Bill C-22 created the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC).[8] FINTRAC is an independent agency responsible for the collection, analysis, assessment and disclosure of information in order to assist in the detection, prevention and deterrence of money laundering and financing of terrorist activities in Canada and abroad. FINTRAC receives reports from financial institutions and intermediaries, analyzes and assesses the reported information, and discloses suspicions of money laundering or of terrorist financing activities to police authorities and others as permitted by its governing legislation. FINTRAC also discloses to the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) information that is relevant to threats to the security of Canada. Concerns were expressed by police and prosecutors that the definition of a “criminal organization” was too complex and too narrow in scope. As a result, in 2002, Bill C-24[9] amended the definition of a “criminal organization” in three main ways by:

Therefore, the definition of “criminal organization” now requires that a group, however organized, meet two requirements: (1) be composed of three or more persons in or outside Canada; and (2) have, as one of its main purposes or main activities, the facilitation or commission of one or more serious offences that, if committed, would likely result in the direct or indirect receipt of a material benefit, including a financial benefit, by the group or by any of the persons who constitute the group. The Criminal Code[11] expressly provides, however, that the term “criminal organization” does not mean a group of persons that forms randomly for the immediate commission of a single offence. A “serious offence” is defined as an indictable offence for which the maximum punishment is imprisonment for five years or more, or another offence that is prescribed by regulation. Facilitation of an offence does not require actual knowledge of a particular offence or that an offence actually has been committed. Committing an offence means being a party to it or counselling any person to be a party to it.[12] The finding by a court that a group is a criminal organization is done on a case-by-case basis and is only applicable to the individuals in that case. For example, the Hells Angels[13] has been found by the courts to be a criminal organization but there is no official directory of such a finding nor will there be continuous labelling. In other words, the existence of a particular group as a criminal organization must be proven anew in every case. There are three specific Criminal Code offences in relation to criminal organizations. One is participation in the activities of a criminal organization (s. 467.11 of the Criminal Code; punishable by a term of imprisonment not exceeding five years). This enables police to investigate and charge persons who fulfill a role that furthers the ability of the criminal organization to commit criminal acts. This may include, for example, individuals who launder money for a criminal organization, facilitating the concealment of the illegal proceeds of criminal organizations. In 2010, Statistics Canada reports there were 10 violations of section 467.11, with 26 persons accused of this offence.[14] A second offence is commission of an offence for a criminal organization (s. 467.12 of the Criminal Code; punishable by a term of imprisonment not exceeding 14 years). It provides for those who commit various criminal offences such as drug importation, drug exportation, extortion, arson, kidnapping, violence, gaming, and money-laundering from which the organization derives a benefit. Statistics Canada reports there were 39 violations of section 467.12 in 2010, with 85 persons accused of this offence.[15] Instructing the commission of an offence for a criminal organization is the third offence and is punishable by imprisonment for life (s. 467.13 of the Criminal Code). Statistics Canada reports there were 50 violations of section 467.13 in 2010, with 39 persons accused of this offence.[16] Sentences for all three types of offences must be served consecutively with any other sentence.[17] At the same time as these offences were added to the Criminal Code, new investigative tools to be directed against criminal organizations were also created. These included special peace bonds,[18] new powers to seize proceeds of crime by broadening the definition of a “designated offence” from which proceeds could be seized,[19] greater powers to resort to electronic surveillance,[20] and a new reverse onus bail provision for those charged with the new offences.[21] It should be noted that membership in a criminal organization is not an offence. Sections 467.11 and 467.12 do not require that the accused be part of the group that constitutes the criminal organization, but this is a requirement under section 467.13. It should also be kept in mind that other Criminal Code provisions may be applied in organized crime situations. These other provisions include: conspiracy (section 465), forming an intention in common to carry out an unlawful purpose (section 21), aiding and abetting (section 21) and counselling (section 22) a person to commit a crime. These Criminal Code provisions should be read in combination with the provisions that define the three criminal organization offences. The law concerning organized crime found in the Criminal Code is still relatively new. In Ontario, the R. v. Lindsay[22] case in 2005 determined that the Hells Angels were a “criminal organization” as that term is defined in the Criminal Code. More specifically, the court was satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt that the Hells Angels has as one of its main purposes the facilitation of one or more serious offences that would likely result in the receipt of a financial benefit by its members, in particular drug trafficking. This was the first time in Canada that a judge declared a group, as opposed to individuals, to be a “criminal organization” as that term is defined in the Criminal Code. In R. c. Aurélius, a street gang was declared to be a “criminal organization” and some offenders in that gang received enhanced sentences as a result.[23] In that case, members of a street gang trafficked in cocaine for the benefit of a criminal organization in the terms encompassed by section 467.12 of the Criminal Code. As a result, some members of this particular street gang were found guilty of “gangstérisme” (gangsterism). In a brief to the Committee looking at trends in organized crime prosecutions,[24] it was suggested that it is often difficult to justify laying Criminal Code criminal organization charges (rather than simply proceeding with the underlying charges) due to the increased complexity that such charges bring to the prosecution. The opportunity to seek consecutive sentences mandated by section 467.14 of the Criminal Code is often offset by the added time and effort involved in proving criminal organization offences. In addition, charging additional, peripheral figures involved in a criminal organization might unduly complicate the prosecution. The complexity and dedication of resources required to prosecute criminal organization offences was brought home to this Committee by a prosecutor with the Quebec Organized Crime Prosecutions Bureau.[25] The successful prosecutions of members of the Hells Angels in Quebec and the break-up of the Bandidos biker gang in Quebec were attributed to the combined effect of the above-noted legislative changes along with other measures. These additional measures included:

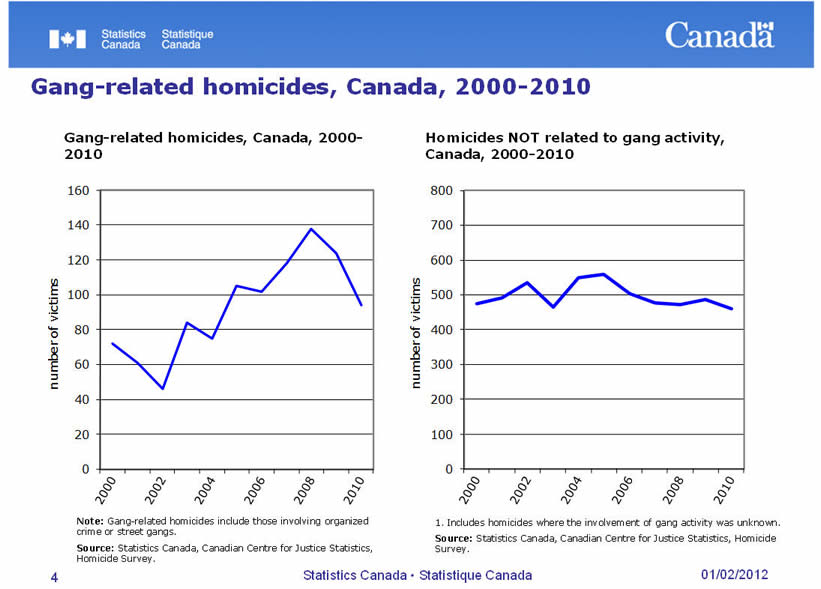

In addition to the laws concerning criminal organizations specifically, laws of general application can be used to prosecute and disrupt organized crime. The Halifax Regional Police, for example, has put in place Operation Breach.[26] In response to the fact that the majority of crimes are committed by a limited number of offenders, Operation Breach strictly monitors offenders released into the community to ensure compliance with release conditions and prevent further criminal behaviour. The goal of Operation Breach is to make certain that persons believed to be actively involved in further offences comply with their release conditions. Non-compliance results in new charges, which in turn results in more restrictive conditions or the offender being returned to custody. The Halifax Regional Police believe that Operation Breach has shown that the enforcement of release conditions has a deterrent effect and can reduce crime. A related effort is to ensure that arrest warrants are executed. This enhances community safety by reducing criminal opportunities for those illegally at large who will now be arrested and, therefore, will not be able to engage in further criminal activity. CRIMINAL ORGANIZATIONS IN CANADAIn 2008, over 900 organized crime groups were identified in Canada, including approximately 300 street gangs.[27] In 2011, Criminal Intelligence Service Canada (CISC) identified 729 crime groups.[28] The change in the numbers of criminal groups is said to reflect a number of factors including fluidity in the criminal marketplace, disruptions by law enforcement, and changes in intelligence collection practices. In its 2010 Report on Organized Crime, CISC focused on street gangs, stating that, since 2006, there has been an increase in the number of such gangs identified by law enforcement agencies across Canada. The factors that may account for this increase include higher-level organized crime groups being identified as street gangs, cells from larger gangs being identified as new entities, street gangs splintering into smaller criminal groups, or gangs changing names.[29] CISC’s main purpose has been to facilitate the timely production and exchange of criminal intelligence information within the Canadian law enforcement community. CISC supports the effort to reduce the harm caused by organized crime through the delivery of strategic intelligence products and services and by providing leadership and expertise to its member agencies. CISC is an umbrella organization of all Canadian law enforcement agencies and as such, is encouraged by all stakeholders and member agencies to actively pursue an impartial autonomous role within the complex network of relationships it manages. In its testimony before the Committee, CISC categorized organized crime groups in Canada into four levels of threat. Category one groups pose the most significant level of threat and operate inter-provincially or internationally. Twenty-four criminal organizations currently belong to this category.[30] Category two groups operate with international or inter-provincial scope as well, but have been determined to be at a lower threat level than the category one groups. There are 262 such groups in Canada today. Category three groups are confined to a single province, but can encompass more than one city or region; 121 category three groups operate in Canada. Finally, category four groups are confined to a single area, such as a town or a city; 210 criminal organizations belong to this category. The number of groups in each category remains fluid. CISC did not rate 30 groups for various reasons and 82 groups came to CISC’s attention after its national threat assessment was compiled.[31] Nationally, the Lower Mainland of British Columbia, Southern Ontario and Greater Montréal are considered to be the primary criminal hubs, with both the largest concentration of criminal organizations as well as the most active and dynamic criminal markets. In 2010, of the 56 gang-related homicides committed in Canada’s ten largest cities, 82% were committed in Toronto, Montréal, and Vancouver.[32] The RCMP in Toronto informed the Committee that adaptability is the cornerstone of the survival and success of organized crime.[33] CISC reports that, traditionally, organized crime was thought to be composed of hierarchically structured groups that were ethnically, racially, or culturally homogeneous and that tended to operate within a strict culture of rules and codes. Today, however, CISC reports that law enforcement is detecting more multi-ethnic criminal groups. There has also been an evolution in the way organized crime groups operate away from an authoritarian, rule-bound structure towards one that is more loosely structured. These groups now have fluid linkages between members and associates, with a diverse range of leadership structures.[34] The different organized crime groups forge alliances which are fluid in both duration and scope. The purpose behind these alliances is the acquisition and legitimization of wealth. The growth of criminal organizations from diverse cultural backgrounds was also reflected in a report the Committee received on organized crime in Quebec.[35] The 2009 Situation Report breaks down organized crime in Quebec into the following categories: Asian-origin organized crime; Aboriginal-origin organized crime; Italian-origin traditional organized crime; Quebec-origin traditional organized crime; street gangs; Latin-American-origin organized crime; East European-origin organized crime; Near- and Middle-East-origin organized crime; and criminal bikers. The police have observed a number of alliances or associations forming within the criminal community of that province. When these prove necessary to the success of their criminal enterprises, organized crime members do not hesitate to employ the expertise of other criminals. One example of such cooperation is the agreement between Italian-origin traditional organized crime and the criminal bikers to allocate territory for drug distribution purposes. Violence can erupt, however, during struggles to control crime groups and during struggles between these groups to control criminal markets. The Committee was also informed that emerging organized crime groups are less inclined than their predecessors to display outwardly and blatantly the signs or “brands” of more traditional groups (e.g. the Hells Angels symbol on jackets). These newer groups tend not to use a particular name, tattoo, clothing, or jewellery as identifiers. This tends to make prosecutions under organized crime laws more difficult.[36] Another trend in organized crime has been that of globalization. Just as in the legitimate business world, there has been an increase in organized crime’s scope of operations with national and international connections now being the norm.[37] CRIMINAL ORGANIZATION ACTIVITIESOne fact about the activities of organized crime that was emphasized many times before the Committee is that they are all centred upon the profit motive. This has many implications, one of which is that organized crime does not restrict itself to one market or one geographical area. It will go where there is money to be made. Cross-jurisdictional crime, in turn, makes it necessary for different law enforcement agencies to work together and share information. Illicit drugs continue to be the largest criminal market in Canada with 57% of the criminal marketplace being taken up by the trade in drugs. The majority (83%) of organized crime groups are involved in the illicit drug trade. The predominant drug is cocaine, followed by cannabis, and then followed by synthetic drugs.[38] One indication of the size of the drugs trade is that, in the Atlantic region, since 2008, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) has seized more than $176 million in drugs arriving at Atlantic ports in sea containers. The majority of these drug seizures consist of hashish coming from Asia and Africa and cocaine arriving from South America.[39] One of the challenges in identifying suspect containers is the use of legitimate companies by organized crime to conceal drug shipments. Of the 109 organized crime groups profiled for the Atlantic provinces, 99 are involved in the illicit drug trade and in Nova Scotia, organized crime accounts for 90% of the drug trade.[40] Canada has also become a source country for synthetic drugs (like ecstasy and crystal meth). Organized crime groups smuggle in the precursor chemicals from source countries such as China and India. Canada continues to export significant quantities of ecstasy and methamphetamine to meet expanding international market demands.[41] One of the features of organized crime is its determination to establish a monopoly on the production, distribution, and sale of illicit goods in any given market.[42] This is one aspect of organized crime operating as a business. Learning about the limitations and effectiveness of law enforcement investigative techniques through the disclosure required by law, organized crime figures no longer have assets in their names, they lease vehicles, they use nominee companies, and they own assets abroad. Moreover, organized crime specializes in certain areas and changes the sectors in which it operates to those with less risk and greater profits. Where law enforcement successes have disrupted or dismantled specific crime groups, this impact tends to be short-term. It creates a temporary void into which market expansion occurs, or creates opportunities for well-situated organized criminal groups to exploit. In general, criminal markets are highly resistant to long-term disruption, as consumer demand in Canada is large enough for criminal networks to continue their activities and for other criminal groups to take the place of those broken up by police.[43] In 2011, CISC reported that financial crime accounts for approximately 11% of criminal market activity. Payment card fraud is by far the largest part of this market and it continues to expand.[44] Payment card fraud involves card thefts, fraudulent card applications, fake deposits, and skimming or counterfeiting. Securities and mortgage fraud is another area of the financial crime market in which organized crime has an interest. The remaining 32% of criminal market activity is taken up with other illicit goods and services. These criminal activities include theft, contraband such as alcohol and tobacco, the sex trade, and human trafficking. The Committee was informed that the largest amount of human trafficking taking place in Canada is domestic, that is, Canadian girls are being trafficked within Canada. This trafficking is done through organized crime networks.[45] CISC has reported that street gangs facilitate the recruitment, control, movement and exploitation of Canadian-born females in the domestic sex trade, primarily in strip bars in several cities across the country.[46] In its meetings held in six cities across Canada in addition to hearings in Ottawa, the Committee learned of the wide array of organized crime groups and activities. In some areas, the traditional “Mafia-style” organized crime groups held considerable sway while in others, Aboriginal or other ethnically-based gangs were the local criminal power. Trafficking in illicit drugs seemed to be a common component of organized crime activities, with other areas being human trafficking, counterfeit products, illegal gambling, money laundering, and vehicle theft. Another aspect of organized crime that was frequently discussed during the Committee’s hearings was the violence that has been experienced when organized crime groups come into conflict with each other over control of lucrative markets, such as supplying illicit drugs. This violence is exacerbated and can involve innocent bystanders when firearms are used. Finally, witnesses in a number of cities discussed the expansion of organized crime into “legitimate” business sectors, such as construction. This mixing of legitimate and illegitimate can make singling out and prosecuting organized crime groups more problematic. The activities listed above can all generate wealth and there is a reduced risk to the criminal organization when that activity is not trafficking in illicit drugs. In cases of tobacco smuggling, for example, the profits can be as high as they are for drug smuggling, but the risk of prosecution and the punishment following conviction is much lower.[47] Criminal organization activities are also being abetted by a new kind of accomplice, usually called a “facilitator”. These are experts in a certain field, often members of a professional order, such as lawyers and accountants. They are not forced to work with a criminal organization but rather, choose to do so due to the generous compensation they receive. These professionals are sought out because of their expertise, and, also, the rules of confidentiality to which they are bound. However, it is often difficult to prove that the facilitator knew that the organization for which he or she performed some work was engaged in illegal activities. Rules such as solicitor-client confidentiality can also make the work of the police in this area more difficult.[48] Criminal organizations have escalated their use of violence in taking over and defending territory. Street gangs have become more violent and unpredictable. In 2010, police reported 94 homicides as being gang-related, compared to 72 in 2000.[49] These include homicides linked to organized crime groups or street gangs, as well as the death of any innocent bystanders during the incident. Furthermore, the victims of gang-related homicides as a percentage of all homicides rose from 13.2 % in 2000 to 17 % in 2010. Most gang-related homicides (56) occurred within Canada's largest census metropolitan areas (CMAs). The 10 largest CMAs accounted for just under half of all homicides in the nation in 2010 (269 out of 554), but 60% of all gang-related homicides (56 out of 94). Police in the metropolitan area of Toronto reported 20 gang-related homicides, the most of any CMA. However, accounting for population, Winnipeg’s four gang-related homicides in 2010 gave it the highest rate among the 10 largest metropolitan areas.[50] The increase in gang-related homicides, in comparison to the number of homicides not related to gang activity, can be seen in the following two charts:

Firearms were used more often in gang-related homicides than in other types of homicide. In 2010, 76% of gang-related homicides in Canada were committed with a firearm, compared to 18% of homicides unrelated to gangs. Among all gang-related homicides that were committed between 2000 and 2010, handguns were used in almost 60% of incidents.[51] By comparison, in homicides not related to gang activity between 2000 and 2010, a handgun was used in approximately 12% of incidents. Knives were the most common weapon used in non-gang-related homicides.[52] Gang members have, therefore, started wearing bullet-proof vests and modifying their vehicles to be armoured. The number of homicides attributable to gangs has generally increased since information gathering on this topic began in 1991 (though it has declined recently), despite the fact that the overall rate of homicides in Canada has generally decreased since the mid-1970s. Moreover, the number of young persons charged with homicides attributable to gangs has generally increased since 2002. The number of youths accused of gang-related homicides peaked in 2007 when 35 youths were accused of this offence, which declined to 10 accused in 2008 and increased to 14 youth accused of committing a gang-related homicide in 2010. Compared to adults, more incidents of homicide involving youth were gang-related. In 2010, among incidents with a youth accused, 25% involved gangs, compared to 12% of incidents with an adult accused.[53] Given the clandestine nature of criminal activities, it is difficult to evaluate the total impact of organized crime in this country, but, given the diversity of criminal markets in Canada, we know it is significant. The overall impact of organized crime is significant due to the spectrum of criminal markets operating in Canada. Some forms of criminal activity are highly visible and affect individuals and communities on a daily basis, such as street-level drug-trafficking, assaults, violence, and intimidation. Conversely, more covert operations, such as mortgage fraud, vehicle theft, and identity fraud, pose long-term threats to Canadian institutions and consumers.[54] Another difficulty in evaluating the impact of organized crime in this country is that the Committee has been told that only about one-third of crimes committed in Canada are reported to the police, but police statistics are widely used as representing the actual crime rate. As a result, policy makers, the media, the legal system and the public can be misled.[55] The Committee was urged to look at the Statistics Canada report, Criminal Victimization in Canada,[56] as a more accurate measure of the amount of criminal activity in Canada. The General Social Survey from 2009, which was the genesis of the victimization survey, indicated that about 7.4 million Canadians – just over one-quarter of the population aged 15 years and older – reported being victimized one or more times in the 12 months preceding the survey, but only 31% of criminal incidents came to the attention of police in 2009.[57] The Committee was informed that a problem with respect to accurately portraying current crime statistics is that the Criminal Victimization Survey is only carried out by Statistics Canada once every five years. As a result, the media tend to pay more attention to annual reports of crimes reported to police. We were told that the current widely used approach of equating crime reported to police as an indicator of the total extent of crime was wrong, misleading and in need of change.[58] A number of caveats need to be raised when trying to compare the results of victimization surveys with the amount of crime reported to the police. In Canada, there are two primary sources of data on the prevalence of crime: victimization surveys such as the General Social Survey (GSS), and police-reported surveys such as the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey. These two surveys are very different in survey type, coverage, scope, and source of information. The GSS is a sample survey, which in 2009 sampled about 19,500 individuals aged 15 years and older. In contrast, the UCR survey is a census of all incidents reported by police services across Canada. While the GSS captures information on eight offences, the UCR survey collects data on over 100 categories of criminal offences. Another key difference between the two surveys is that the UCR survey records criminal incidents that are reported to the police and the GSS records respondents’ personal accounts of criminal victimization incidents. Many factors can influence the UCR police-reported crime rate, including the willingness of the public to report crimes to the police, reporting by police to the UCR survey, and changes in legislation, policies or enforcement practices. One way to estimate the extent of crime that is not reported to police is through the GSS victimization survey. Because the GSS asks a sample of the population about their personal victimization experiences, it captures information on crimes, whether or not they have been reported to police. The amount of unreported victimization can be substantial. For example, the 2009 GSS estimated that 88% of sexual assaults and 77% of household property thefts were not reported to the police. As a result, victimization surveys usually produce much higher rates of victimization than police-reported crime statistics. Despite this, the 2009 GSS also reported that 93% of Canadians felt either very or somewhat satisfied with their personal safety, indicating they felt as safe as they had in the 2004 GSS; 90% of respondents reported that they felt safe when walking alone in their neighbourhood at night. The GSS also asked Canadians about their perception of crime in their communities; 62% of respondents said they believed crime rates in their community had not changed over the past five years.[59] Despite the benefits of victimization surveys, they do have limitations. For one, they rely on respondents to report events accurately. They are also only able to address certain types of victimization. They do not capture information on crimes that have no obvious victim (e.g. prostitution or impaired driving), where the victim is a business or school, where the victim is dead (as in homicides), or when the victim is a child (anyone under the age of 15 in the case of the GSS). RECOMMENDATION The Committee recommends that Statistics Canada carry out the Criminal Victimization Survey annually, and that the Government of Canada provide Statistics Canada with the appropriate funds to do so, in order to give policy makers, police, the justice system and the public a better measure of criminal activity in Canada. ORGANIZED CRIME IN PRISONSThe introduction of anti-gang legislation, coupled with integrated and aggressive police investigations, has reportedly led to an increase in the number of gang members and their associates under the jurisdiction of the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC). The Committee was informed that, as of November 30, 2011, 2,293 offenders under CSC’s jurisdiction were identified as members or associates of a criminal organization. Of these offenders, 70% (or 1,605) were incarcerated and 30% (or 688) were under some type of community supervision. The overall offender population under CSC supervision was 23,021, meaning that the gang population comprised 9.96% of the overall offender population.[60] The most common type of criminal organization is street gangs with 39% of the national prison gang population. The street gang population within CSC has grown rapidly in the past 10 years and CSC predicts a continuation of this trend in the future. The second largest criminal organization type under CSC jurisdiction is Aboriginal gangs with 26% of the population, followed by motorcycle gangs (17%), traditional organized crime (8%), other gangs (7%), and Asian gangs (3%).[61] The street and Aboriginal gangs, which combine to account for 76% of the organized crime affiliations within CSC, are predominantly weighted in the Prairies region, which manages 83% of the Aboriginal gang members and 38% of the street gang population. The increase in gang members under CSC jurisdiction has created a number of challenges: