SECU Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

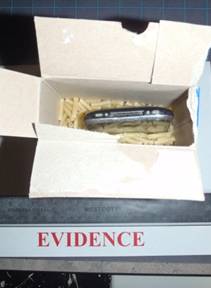

DRUGS AND ALCOHOL IN FEDERAL PENITENTIARIES: AN ALARMING PROBLEMCHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTIONDrugs and alcohol in prisons pose a challenge for the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC), which is responsible for managing and administering the sentences of federal offenders. To combat this problem, CSC implemented a national drug strategy several years ago, under which it does not tolerate the presence or consumption of drugs or alcohol inside its institutions. The policy objective states that a “safe, drug-free institutional environment is a fundamental condition for the success of the reintegration of inmates into society as law-abiding citizens.”[1] Despite CSC’s efforts to prevent the introduction of illegal drugs, they continue to cause challenges in the correctional system. As we know, any illicit drugs on penitentiary grounds were brought there illegally, and they help fuel internal black markets while also strengthening external networks of organized crime both inside and outside of penitentiaries. Inside, the use of drugs by offenders and their trafficking often lead to institutional violence and create difficulties in managing the inmate population. This problem has an impact on a number of critical issues, such as providing a safe institutional environment for both staff and inmates, as well as ensuring an atmosphere that promotes inmate rehabilitation and reintegration. 1.1 COMMITTEE’S APPROACH AND MANDATEOn 27 September 2011, the Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security (the Committee) agreed “to study the issue of drugs and alcohol in prisons, how they enter the prisons and the impacts they have on the rehabilitation of offenders, the safety of correctional officials and on crime within institutions.”[2] From 29 September to 8 December 2011, the Committee held a total of 10 public hearings in Ottawa. Throughout its study, the Committee gathered evidence from representatives of CSC, the Union of Canadian Correctional Officers, the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies, the John Howard Society of Canada, Prison Fellowship Canada, the Office of the Correctional Investigator (OCI), the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, the Prisoners with HIV/AIDS Support Action Network, and numerous individuals currently or formerly involved in policing and corrections.[3] Among the many CSC witnesses who appeared, the Committee heard from officials from correctional facilities of various security classifications. Specifically, the witnesses came from the medium security Stony Mountain Institution in Manitoba, the medium security Drumheller Institution and multi-level Edmonton Institution for Women in Alberta, and the maximum security Regional Treatment Centre in Kingston, Ontario. In order to gain greater insight into the daily challenges facing not only correctional officers, but also all correctional staff working with inmates with substance abuse problems, the Committee decided to visit two federal institutions. The Committee travelled to Kingston, Ontario, to the Collins Bay and Joyceville medium security institutions for men. During the trip, Committee members had the opportunity to speak directly with CSC staff and representatives of the Inmate Committee. Given that the presence of drugs and alcohol in correctional institutions is a problem across the country, the Committee wanted to learn more about this issue and as a result invited witnesses from the Yukon Territory. Their work and personal experiences gave the Committee a deeper appreciation of how this problem affects most correctional facilities in Canada. 1.2 STRUCTURE OF THE REPORTThis report summarizes the evidence heard and knowledge accumulated by the Committee in the course of its study. It seeks to identify the common themes that emerged from the evidence presented by the various witnesses, while also highlighting specific concerns. This report is divided into four chapters, including this first one. The second chapter presents an overview of the problem and the various issues that result. The third describes the tools available to CSC for preventing the introduction of drugs, rehabilitating offenders and managing a complex and diverse inmate population. The fourth presents the Committee’s observations, outlines the progress made to date and provides recommendations to help CSC meet these challenges and achieve its objectives in administering the sentences of federal offenders with substance abuse problems. CHAPTER 2: OVERVIEW OF THE PROBLEM AND ISSUESThe presence of drugs and alcohol in correctional institutions is not a new phenomenon, and the methods used for smuggling in drugs are quite ingenious. Stamping out supply and demand is all the more complex given that each institution, whether for men or women, regardless of security level, faces unique challenges. It must be stated at the outset that it is virtually impossible for the Committee, within the scope of this study, to address the full extent of the problem of drugs and alcohol in federal institutions. The Committee can only highlight an elusive problem that is difficult to solve. The following is what Canada’s Correctional Investigator Howard Sapers had to say on the subject: Eliminating drugs and alcohol from prison appears deceptively simple, but has proven to be very difficult and costly in practice. The problem of intoxicants in prison is difficult to measure and therefore difficult to monitor. Drug supply and utilization are illegal and underground activities. It’s extremely difficult to generate a reliable number, or predictor, of the extent of the drug problem inside Canadian penitentiaries. We know that drugs are in prisons. We simply don’t know the extent of the drug use.[4] The Committee also learned from the evidence gathered throughout its study that the problem is not limited to the introduction of illicit drugs and the production of brews. CSC must also attempt to prevent the introduction of tobacco, prohibited items and the diversion of legal drugs, which also jeopardize the safety and security of institutions. 2.1 HOW ILLICIT DRUGS AND OTHER PROHIBITED SUBSTANCES ENTER FEDERAL CORRECTIONAL FACILITIESThe various methods used to smuggle illicit drugs and other prohibited substances into federal correctional institutions are constantly evolving. As such, the problem is complex, multi-dimensional and difficult to resolve. For a better appreciation of the obstacles facing CSC, it must be remembered that penitentiaries are not closed environments and that many people enter and leave them each day. Drugs may be brought in by visitors, staff and inmates or thrown over the institution’s security perimeter. According to Pierre Mallette, National President, Union of Canadian Correctional Officers, the constant back and forth movement between the institution and the community has a significant impact on the likelihood of criminal activity. Visitors could be “family, friends, community groups, inmates’ rights groups, entrepreneurs and contractors.”[5] He added that, in six months, up to 5,000 visitors may pass through an institution. According to him, the more visitors, the higher the chances for increased criminal activities. The diagram distributed by CSC on drug subculture shows the various networks that intimidate and pressure individuals to smuggle drugs into a facility.[6] While the diagram does not illustrate the most complex network that could exist, it does provide a representative view of the potential number of individuals involved. Witnesses explained that families of inmates are also pressured to smuggle drugs into penitentiaries. Mr. Mallette gave one example where the mother felt discouraged and obligated to smuggle drugs into the facility out of love for her child. In other cases, the inmates themselves attempt to smuggle drugs, for example, when an inmate leaves the facility on a type of conditional release and then returns. Mr. Kenneth Putnam, who appeared as an individual, talked about his son, who committed suicide after years of struggling with alcoholism and drug addictions. Mr. Putnam explained to the Committee that correctional facilities are like communities. There is a hierarchy, and the inmates who have committed the most serious crimes are usually responsible for overseeing the drug trade. This makes inmates who have drug addictions even more vulnerable and at the mercy of the tougher inmates. Mr. Putnam gave his son as an example. His son felt he had to bring drugs into the facility because “there was an expectation for him to do this”[7] and that, if he did not follow through, he would suffer the consequences. The following pictures show how people smuggle drugs or other illicit substances. Tobacco, drugs or contraband such as cell phones or syringes are often hidden inside personal items meant for a specific inmate. CSC has found such objects hidden inside pens, food and clothing.

The Committee was informed that maximum security facilities have the highest security features which limit access to the outside world. Inmates in maximum security pose a heightened risk to staff, other inmates and the community. Their movements and opportunities to associate are governed by a very strict set of rules. There is less back and forth movement between the facility and the community than is the case with medium security facilities, and far less movement than in a minimum security facility. Don Head, Commissioner of Correctional Service Canada, explained that CSC has more control over the sources of drug entry in maximum security institutions because they are better known. He added that “[m]ediums are a little more problematic. Minimums are a different situation altogether.”[8] Maximum security institutions are not drug-free, however. In fact, maximum and medium security institutions are often located in wooded areas, making them vulnerable to “throw-overs”.[9] Drugs are hidden inside tennis balls, arrows and even dead birds, which are then projected from about 150 metres beyond the institution perimeter using a bow, slingshot or potato gun. The following pictures show examples of throw-overs located by CSC.

The Committee also learned that in some regions, such as Kingston, there may be more than one institution on a plot of land. The Committee was told that the close proximity of a medium security institution to a minimum security institution makes controlling drug entry points even more difficult. Quite a few witnesses pointed out that the elimination or timely detection of drugs and alcohol is complicated by the fact that, when the supply to one illicit substance is cut off, inmates resort to other intoxicants. In many cases, inmates turn to producing homemade alcohol or “brews.”

It should be noted that the demand for tobacco has increased since it was banned from penitentiaries.[10] Commissioner Head pointed out the following: Regarding tobacco, as a result of our implementing a tobacco ban within our federal penitentiaries, tobacco has taken on a much higher value within our penitentiaries. Tobacco is a significant currency among the inmate population. We now have a few staff who are being enticed by offers of money to bring tobacco into our institutions. For us, this is a slippery slope to bringing other things in that we don't want them bringing in. We’re finding that individuals are being offered—not just staff, but family members, other people in the community—anywhere from $200 to $2,000 to bring in a pouch of tobacco. Tobacco is not an illegal substance—it’s just unauthorized. So people are being enticed. They think the worst they’re going to get is a slap on the hand. It’s just a little bit of money. Who’s going to know the difference? Unfortunately, for us it’s a slippery slope—people get hooked by bringing tobacco into the institutions. The next thing is that within the package there are a couple of pills, a few containers of hash oil. But don’t worry: it’s just one package of tobacco and one package of drugs. But the next thing you know, we have violent incidents.[11] With regard to employees involved in illicit activities, the Commissioner did say that only a very small percentage of a base of about 18,000 staff have been implicated. He added that those who engaged in such activities in the past were charged and dismissed.[12] The introduction of drugs or contraband is not limited to the above circumstances. The power and influence that gangs and organized crime networks exert in prisons and in the community should not be underestimated. The number of inmates affiliated with a gang has increased, and the majority were already involved with gangs prior to incarceration.[13] “Currently there are approximately 2,200 offenders who have gang affiliations, and there are over 50 different gangs inside our institutions across the country.”[14] The drug subculture is therefore alarmingly complex. Although bank transactions[15] are monitored by CSC, witnesses noted that inmates who work in canteens[16] and have ties to criminal organizations further complicate CSC’s work. It follows that some of the criminal activity that occurs in institutions is directly related to the influence of gangs and organized crime and is closely related to institutional violence. This makes managing these various prison populations an enormous challenge. [T]he institutional drug trade, which includes the improper use of prescription drugs, is a major source of institutional violence. The drug trade is often controlled or influenced by gang activity and the presence of organized crime. In prison as well as on the street, the drug trade is associated with predatory behaviours, such as intimidation, muscling and extortion. Within Correctional Service Canada facilities, it is estimated that gangs are involved in close to 25% of the major security incidents.[17] What makes the situation even more problematic is that penitentiaries are not isolated from the outside world, and inmates have contact with the broader community by telephone. Despite the fact that inmates have a very limited list of people authorized to receive their calls, Mr. Mallette told the Committee that authorized individuals may transfer the inmate’s call to a third person.[18] In this way, inmates can continue to carry out their illegal activities from inside the institution. Inmates also use contraband cellphones for this purpose. Witnesses also noted other problems involving bank transactions carried out by telephone and over the Internet to a third party in the community, beyond CSC’s reach. Andrea Markowski, Warden of CSC’s Edmonton Institution for Women, told the Committee that concerns about the sources of drugs being introduced are different for women’s institutions. She said that women’s institutions do not have as many problems with throw-overs since women have far fewer contacts on the outside. However, the ability of women to hide drugs or tobacco inside a body cavity for long periods of time poses a problem. She added: We have other challenges. The women are on a lot of medications for various health and mental health issues. We have diversion challenges that I think are more prevalent than they are in the men’s facilities. Those would be for methadone and other medications that they might be pressured to share, or that they might sell because they want resources for other things, such as the canteen.[19] 2.2 THE IMPACT OF DRUGS AND ALCOHOL IN FEDERAL CORRECTIONAL FACILITIESThere are a number of consequences arising from the presence of drugs and alcohol in penitentiaries, but only by first depicting the complexity of the incarcerated population can we understand the magnitude and seriousness of the situation. Upon admission, 80% of offenders have a serious substance abuse problem, and over half of them reported that alcohol and drug use was a factor in the commission of their offence.[20] Mental health problems are also highly prevalent among inmates in the correctional system. Experts note that drug addicts and inmates with mental health issues generally have complex problems to contend with, such as concurrent mental health issues, drug addiction and alcoholism. Dr. Sandy Simpson, Clinical Director of the Law and Mental Health Program at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, said that substance abuse “is a driver of mental ill health and it is also a barrier to recovery, wellness, and reducing recidivism.”[21] This is all the more alarming since “anywhere up to 90% of a standing prison population will have a lifetime problem of substance misuse or dependence.”[22] The Commissioner also raised this point with the Committee, noting that “[t]his dependency does not magically disappear when they arrive at our gates.”[23] Dr. Jan Looman, Clinical Manager of the Regional Treatment Centre in Kingston, underscored the difficulties associated with mentally ill offenders in the federal inmate population. For example, he noted that “mentally disordered offenders can be victimized by higher-functioning offenders, which increases their stress.”[24] He also added that: Drug activity often leads to muscling behaviour and the use of weaker offenders to hold or transport drugs. All of this negatively impacts the institutional environment and therefore diminishes the ability of offenders to benefit from programming.[25] Witnesses also noted the overrepresentation of Aboriginal offenders in prisons. According to CSC, over 90% of Aboriginal offenders have substance abuse problems,[26] and therefore culturally specific programming is required. As noted by Commissioner Head, CSC currently offers substance abuse programs tailored to Aboriginal offenders. This special programming is an integrated approach to corrections that combines traditional correctional program principles with those of Aboriginal healing. Witnesses stressed the importance of acknowledging the particular needs of women in the correctional system. The women offender population makes up the fastest growing inmate population, second only to Aboriginal women. Women offenders must often contend with serious substance abuse and mental health problems, and many of them have also been physically abused.[27] Other witnesses highlighted that HIV and hepatitis C rates among offenders are on the rise and that some inmates in the correctional population have problems related to pain management. The Committee also heard that inmates with substance abuse problems may engage in destructive behaviour when they are desperate to feed their addiction, which also puts public health at risk since the vast majority of inmates eventually return to the community. There are also serious public health implications related to offenders’ addiction to intravenous drugs. Our data shows that one in five male offenders has injected drugs in his lifetime. Of these, half report having injected in the year prior to incarceration. Intravenous drug users have a much higher incidence of blood-borne diseases, such as hepatitis C and HIV, than the general population. The reality is that we are dealing with one of the most seriously addicted segments of Canadian society, evidenced by the lengths they go to, and the crimes they commit, to obtain and use drugs.[28] In short, witnesses were unanimous in highlighting this alarming problem and the need to take action: Substance abuse is the most important issue we must address if we are to help offenders move through their correctional plan and return to the community as productive, law-abiding citizens. Dealing with the issues of substance abuse is also important for the stability of our institutions across Canada. Addicted offenders are prone to violence and will seek any means necessary to feed their addiction. These factors put institutional staff, as well as the offender population, at risk.[29] We agree that the situation of drugs in prison is serious. It creates violence, it spreads disease, and it can lead to further crime. We agree that efforts should be made to reduce the amount of illicit drugs in the institutions.[30] Drug and alcohol addiction is one of the primary symptoms of offender mental health and resultant criminal behaviour. We support the focus being put on eliminating drugs and alcohol from the prisons.[31] There is little doubt that the presence of illicit drugs and alcohol in federal prisons is a major safety and security challenge. The smuggling and trafficking of illicit substances and the diversion of legal drugs inside federal penitentiaries present inherent risks that ultimately jeopardize the safety and security of institutions and the people who live and work inside them. I commend the committee for taking on this very important and complex review.[32] CHAPTER 3: TOOLS AVAILABLE TO THE CORRECTIONAL SERVICE OF CANADA TO FIGHT AGAINST THE INTRODUCTION OF DRUGS AND TO ENCOURAGE OFFENDER REHABILITATIONAs described in the previous chapter, CSC is responsible for an inmate population that is becoming more and more complex and diverse. This chapter presents an overview of the various tools that were mentioned during the course of our study that are at CSC’s disposal to prevent the introduction of drugs into facilities and to encourage offender rehabilitation. These tools include the Corrections and Conditional Release Act and various policies, harm-reduction measures and drug interdiction methods, as well as correctional programming. CSC is responsible for an average of 14,200 federally incarcerated offenders and 8,600 offenders in the community. Including all admissions and releases in the 2010‑2011 fiscal year, CSC managed a total of 20,233 incarcerated offenders and 13,971 supervised offenders in the community.[33] This represents an increase over recent years with respect to incarcerated offenders,[34] and this trend is expected to continue as recent and proposed legislation will result in more convicted offenders being incarcerated in federal institutions.[35] CSC manages 57 institutions, 16 community correctional centres, and 84 parole offices and sub-offices across the country. 3.1 PRINCIPLES OUTLINED IN THE CORRECTIONS AND CONDITIONAL RELEASE ACTThe purpose of the correctional system is to contribute to the maintenance of a just society by ensuring that sentences are carried out safely and humanely and that appropriate programs are offered in penitentiaries and in the community to assist in the rehabilitation of offenders and their reintegration into the community as law-abiding citizens. Part 1 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act sets out the legislative basis of CSC. It sets out the principles that must guide the actions of CSC and its responsibilities. For example, the Act provides specifically that CSC must offer a range of programs, including programs specifically for women and Aboriginal people.[36] In the course of its study, the Committee learned about the wide range of programs offered by CSC to address the needs of offenders and contribute to their reintegration into society. For example, CSC offers social, cultural and training programs, as well as core correctional programs that are designed specifically to target criminogenic factors linked to criminal behaviour in offenders and to reduce the risk of recidivism. Currently, CSC offers four core programs, which address family violence, anger management, substance abuse and sex offender treatment.[37] It was explained to the Committee that CSC offers both a high-intensity substance abuse program and a moderate-intensity substance abuse program and that there are also substance abuse programs tailored specifically to women offenders and to Aboriginal offenders. Ross Toller, Deputy Commissioner, Transformation and Renewal Team, Correctional Service of Canada, noted that specialized programming is needed for women and Aboriginal people, “who have unique patterns of substance abuse, and for whom cultural and gender-specific programming is more appropriate.”[38] The Commissioner also informed the Committee of “booster” substance abuse programs for offenders before they transition into the community under supervision, as well as a community maintenance program for offenders who are in the community but still under CSC supervision. At the Joyceville institution, Committee members had the opportunity to visit the industrial metal shop. Inmates make metal lockers as part of the CORCAN program, which gives employment training to offenders. CORCAN’s mission is to provide employment and employability skills training for offenders in order to ease their reintegration into society and reduce the risk of recidivism. The CORCAN program is offered in 31 federal institutions. CSC also operates 53 community employment centres that help offenders find work after their release.[39] The Committee learned during its visit to the Joyceville and Collins Bay facilities that, beyond the core correctional programs, the cultural programs and training programs, CSC also offers faith-based services. Under section 75 of the Act, offenders are “entitled to reasonable opportunities to freely and openly participate in, and express, religion or spirituality”. CSC provides chaplaincy services, most commonly for the Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, Muslim, Sikh and Buddhist faiths, in order to encourage offenders to reintegrate through spirituality. In order to promote a safe correctional environment, the Act provides for various measures including, under certain circumstances, searches of inmates, cells, staff, visitors, and vehicles.[40] The disciplinary system established under the Act is designed to “encourage inmates to conduct themselves in a manner that promotes the good order of the penitentiary, through a process that contributes to the inmates’ rehabilitation and successful reintegration into the community.”[41] Among the disciplinary offences enumerated in the Act are being in possession of, or dealing in, contraband; taking an intoxicant into the inmate’s body; and failing or refusing to provide a urine sample.[42] The Act also sets out the summary conviction offences of possessing contraband beyond the visitor control point in a penitentiary, and of delivering contraband to, or receiving contraband from, an inmate.[43] 3.2 EXISTING HARM-REDUCTION MEASURESCSC may implement various harm-reduction measures to promote public health. This can include, for example, the provision of bleach kits to inmates. Another harm-reduction program offered by CSC is the Methadone Maintenance Treatment (MMT) program. During its visit to the Collins Bay and Joyceville institutions, the Committee had a chance to speak to CSC employees about MMT. Ross Toller also shared with the Committee that methadone treatment in conjunction with correctional programs helps offenders overcome their dependency on illegal drugs. To participate in the program, offenders must meet the eligibility criteria. He added that methadone is administered in the health services area by medical professionals, who supervise the offender to ensure that he or she has swallowed the dose and does not attempt to regurgitate it in order to pass it on to another inmate. CSC has seen reductions in opioid use, criminal activity, and reincarceration among offenders who have participated in the program, and noted that they are more likely to continue treatment once released into the community.[44] 3.3 ANALYSIS OF STRATEGIC AND MONITORING INFORMATIONOver the course of its study, the Committee had the opportunity to meet with security intelligence officers, whose testimony was invaluable in helping members understand the institutional drug subculture. Darcy Thompson, a Security Intelligence Officer (SIO) at the Drumheller institution, pointed out security intelligence officers and analysts collect and analyze information about inmates and their gang affiliations in federal correctional institutions. SIOs communicate with their partners outside of CSC, including local police services, the RCMP, Canada Border Services Agency and Criminal Intelligence Service Canada. CSC expects to have 250 new SIOs in federal institutions across the country by 2012-2013.[45] 3.4 DRUG DETECTOR DOGSWhen the Committee visited the Collins Bay institution, it saw a demonstration of drug detector dogs. They are specially trained to detect specific odours and convey the source of that odour to their handlers through a change of behaviour.[46] The Committee heard that the drug detector dog program also acts as a deterrent. Darcy Thompson explained that visitors’ vehicles often turn around when they see a dog handler’s vehicle parked at the entrance. During both the study and Committee travel, witnesses told the Committee that, to date, there has not been much published research on the effectiveness of the drug detector dog program, and that teams are not always available at all institutions due to resource limitations and the limited number of hours that each dog can work. CSC has recently announced that the number of detector dog teams will be increased. 3.5 TECHNOLOGYThe Committee was informed that CSC is always on the lookout for new technologies to impede drug trafficking. For example, “ion scanners” are used to detect trace amounts of drugs on packages, inmates, staff, and visitors. The Committee heard concerns, however, that ion scanners are very good at detecting trace amounts of certain drugs such as cocaine, but are not as successful at detecting drugs such as marijuana.[47] As well, the Committee heard that, in some instances, the full range of security measures (including ion scanners) is not used on all individuals who enter institutions.[48] CSC is also investigating the use of body orifice scanning system chairs, or BOSS chairs, which use an electronic scan to help determine whether an individual has secreted packages containing drugs in a body cavity. BOSS chairs have been installed at some penitentiaries, but have only been tested on inmates. The Commissioner told the Committee that BOSS chairs have not proven successful in all trials to date.[49] The Committee also learned that radar/infrared systems have been installed at two institutions. These systems allow security officials to track individuals approaching the perimeter day or night, in all weather conditions. Similarly, all maximum security institutions have been equipped with night vision and thermal imaging goggles for enhanced perimeter surveillance. 3.6 THE CORRECTIONAL SERVICE OF CANADA’S BUDGET FOR CORRECTIONAL PROGRAMS (INCLUDING FOR DRUG REHABILITATION) AND DRUG INTERDICTION MEASURESIn 2008, the Government granted CSC an additional $122 million over five years to eliminate illegal drugs in federal institutions. The Committee was informed that this money has been used to date to increase the number of drug detector dog teams, improve security intelligence capacity, enhance perimeter security using new technologies and reinforce search policies.[50] The Commissioner told the Committee that “this funding supports a more rigorous approach to drug interdiction in order to create safe and secure environments where staff and offenders can focus on the business of rehabilitation.”[51] In 2010-2011, CSC spent $410.1 million on “correctional interventions,” which includes offender case management, spiritual services, offender education, CORCAN and correctional reintegration programming (including substance abuse programs).[52] This program activity represented 17.3% of CSC’s expenditures for that fiscal year. Actual spending for the same program activity in 2009-2010 was $416.3 million. In 2010-2011, CSC spent $1,478.5 million on “custody,” which includes institutional management and support, institutional health services, institutional services (including food services), and institutional security (including intelligence and supervision and drug interdiction).[53] This program activity represented 62.2% of CSC’s expenditures for that fiscal year. Actual spending for the same program activity in 2009-2010 was $1,379.5 million. The Committee has also learned that CSC spends approximately 2% of its total operating budget on core correctional programs, including substance abuse programming.[54] Correctional Service of Canada figures from June 2009 include the following breakdown for the various substance abuse programs:[55]

CHAPTER 4: THE COMMITTEE’S OBSERVATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS4.1 RECOGNIZING THE IMPORTANCE OF TOOLS TO BETTER MANAGE A COMPLEX AND DIVERSE INMATE POPULATIONThe Committee recognizes that CSC faces a challenging task in maintaining a safe and secure correctional environment, given the increasing prevalence of mental illness, substance abuse, overcrowding and infectious disease amongst federal inmates. The Committee also heard that, in some institutions, there may be up to nine different sub-populations that need to be kept separate. As terrible as this seems, some institutions have nine populations. There are inmates who are under protection because they have not paid their debt; those who are under protection because they committed sexual offences; and biker gangs who can’t stand each other. [56] Given the complexity of the task of population management under these circumstances, the Committee believes it is important for CSC to have access to a full complement of tools that may assist in motivating offenders in their rehabilitation, deterring drug and alcohol use, and preventing illicit substances from being brought into federal correctional institutions in the first place. 4.1.1. THE CORRECTIONAL PLANSeveral witnesses spoke about the importance of the correctional plan in motivating an offenders’ rehabilitation, including Correctional Investigator Howard Sapers: Every offender is given a correctional plan after intake and assessment. The Correctional Service of Canada prescribes the plans or programs. You have the men and women in the service who are doing those assessments and saying that they think the criminogenic needs of the prisoners will be addressed if the prisoners are in a particular substance abuse or cognitive program. Offenders understand that successful progress against their correctional plan is what the parole board will be looking at. Of course it is a motivator; it is designed to be a motivator for them to be involved and engaged in those programs.[57] The inmate’s progress toward meeting the objectives in his or her correctional plan is taken into account in various decisions, including conditional release.[58] All correctional plans specify that the inmate is expected to remain drug and alcohol free while incarcerated. The correctional plans for inmates with documented drug or alcohol problems must also “identify specific needs and outline the expected and realistic progress towards addressing their problems.”[59] An inmate’s correctional plan may be reviewed and modified in response to drug-related activities. Other witnesses, however, questioned whether inmates are truly engaged with the programs in their correctional plan, or are merely “ticking the box” to show the Parole Board of Canada they have completed a particular program, regardless of whether they have learned from it.[60] Pierre Mallette suggested it may be beneficial to have separate correctional programs for those who are committed to their correctional plans and those who are not, since the latter may be disruptive: We have always felt that we should do everything in our power to help inmates who make a commitment and focus on rehabilitation, by providing them with programs and the necessary tools. However, we are dealing with a group of individuals who are not necessarily interested in committing to their correctional plan. Unfortunately, these people sometimes create problems within the institutions. They can ruin the program for other inmates. There should be a separate program for them. But we need tools for that.[61] Commissioner Don Head expressed appreciation for new incentives that would allow him to encourage offenders to make progress toward meeting the objectives of their correctional plans.[62] Consequently: Recommendation 1 The Committee believes that an inmate’s adherence to their correctional plan is important in the reduction of drugs and alcohol within prisons. The Committee calls on the Government to continue its progress on the expansion of the use of correctional plans. 4.1.2 DISCIPLINARY MEASURES AND/OR CRIMINAL PENALTIES REFLECTING THE GRAVITY OF THE PROBLEMThe Committee believes that a full range of measures, from informal resolution through to criminal penalties, is required in order to respond to the issue of drugs and alcohol in federal correctional institutions. Because the federal correctional environment is becoming more complex and diverse, therefore, some witnesses have suggested that existing measures at CSC’s disposal may not reflect the gravity of the problem. Commissioner Don Head, for example, brought to the Committee’s attention the fact that the sanctions in the Act were developed in 1992, and may not be sufficient to deal with certain behaviours or their consequences, such as positive urinalysis tests.[63] Other witnesses noted that visitors who attempt to introduce drugs into federal correctional institutions may face criminal penalties if resources are dedicated to their prosecution, but that such penalties may not have much deterrent effect for offenders who are already incarcerated and have attempted to influence individuals into bringing drugs into the institution. Pierre Mallette provided a synopsis of this problem: [I]f a visitor is stopped for being in possession of drugs, they can be charged with a criminal offence. It is the responsibility of the police to come and arrest them. In order to deal with offenders who get drugs in, are in custody and have pushed hard to get the drugs, we need the help of the public, judges and crown prosecutors, who must take those offences very seriously. But if the offenders are already in prison, there is no point in bringing them before the court again; they are already in prison. What else could happen? All those things have to be factored in. There have to be consequences for both parties, meaning the people who try to get the drugs in and those who bring them in.[64] Certain issues were brought to the Committee’s attention with respect to the application of the broader criminal law to the federal correctional system. For example, the Committee heard that the criminal justice system may not be structured to recognize the different context of drug trafficking inside federal institutions. Commissioner Don Head stated the following: One of the problems we’ve had […] is that quantities of drugs that come into the institutions are not the same as our cousins seize at the border, as you can imagine. Sometimes local police forces or prosecutors understand the seriousness of small quantities coming in, but they also realize the tremendous workload they have and are not necessarily as keen to pursue it.[65] The Committee heard appreciation, however, for proposed legislation that would establish a mandatory minimum term of imprisonment of two years for drug-trafficking in a prison or on its grounds.[66] This new provision would help highlight that drug-trafficking in prisons is a serious offence that threatens the safety and security of correctional environments and the community at large, regardless of the quantity of drugs being trafficked. The Committee also heard that it is often difficult for correctional officers to pursue suspicious vehicles who have passed the territorial limit of the penitentiary. Christer McLauchlan, Security Intelligence Officer at Stony Mountain Institution, gave the following example: [A]t Stony Mountain Institution last night, our officers detected a vehicle entering the grounds. When that vehicle was confronted by our motor patrol, it fled, nearly running over some of our officers. It was obvious to us that this person was up to no good. Without setting up a roadblock at the bottom of the hill restricting all traffic—that’s the type of challenge we’re facing on a daily basis. […] One of the things the members may not be aware of is that correctional officers are not peace officers when they’re off the penitentiary reserve and do not have immediate custody of an inmate. What that means is that, literally, the officer who was pursuing the vehicle did the right thing, which was to stop at our penitentiary reserve. Once they were gone, he could not pursue them. He would not be a law enforcement officer once he left the penitentiary reserve. [67] The Committee believes that it is important to ensure that CSC has a full range of appropriate tools, including legislative provisions under the Act and the Criminal Code, that reflect the gravity of the problem as it exists in correctional institutions. Consequently, the Committee recommends: RECOMMENDATION 2 That the Government should investigate whether legislative amendments are required with respect to existing disciplinary measures, criminal penalties, and/or the scope of correctional officers’ law enforcement authority in order to help combat drugs and alcohol in federal correctional institutions. 4.1.3 TECHNOLOGICAL SOLUTIONSThe Committee recognizes that technological solutions are invaluable to CSC’s efforts to prevent drugs from entering federal correctional institutions. The Committee was made aware of the importance of existing technology such as ion scanners, and of the possibility that new technologies such as body orifice scanning system chairs (or BOSS chairs) may prove to be useful in detecting illicit substances. Several witnesses alerted the Committee to the issue of contraband cell phones being smuggled into federal correctional institutions for use in organizing drug transactions. One possible technology that witnesses suggested may help to combat this phenomenon is the use of cell phone jamming technology, to block or disrupt cell phone signals. Commissioner Don Head informed the Committee that CSC is currently engaged in discussions with Industry Canada to determine whether cell phone jamming technology could be used in federal correctional institutions. Commissioner Head advised that this technology is governed by specific regulations that may not permit long-term use, and that there may be additional concerns as well, in that the technology may disrupt the wireless devices of CSC managers, or those in neighbouring communities, in addition to interfering with contraband cell phones.[68] The Committee commends CSC on its proactive approach to investigating new technologies that may assist in CSC’s interdiction efforts, and recommends: RECOMMENDATION 3 That the Correctional Service of Canada continue its discussions with Industry Canada to determine whether cell phone jamming technology can be safely used in federal correctional institutions to disrupt cell phones used to arrange drug transactions. 4.2 RECOGNIZING THE IMPORTANCE OF CORRECTIONAL WORKThe Committee wishes to recognize the dedication of the many staff members and volunteers who work in corrections. These men and women provide an essential service to the prison population and the entire community. They do an exceptional job, often under extremely difficult conditions. A number of witnesses spoke about the progress CSC has made in preventing illicit substances from entering institutions. They highlighted the numerous investments that have helped CSC progress toward achieving its objective. Correctional officers and security intelligence officers informed the Committee about the wide range of tools at their disposal that help with the timely detection and interception of drugs. Consequently, the Committee asks: RECOMMENDATION 4 That the Government continue the good work it has done in giving our front-line correctional officers the tools they need to do their job. 4.2.1 CORRECTIONAL OFFICERS AND INMATES – A CRUCIAL RELATIONSHIPSeveral witnesses acknowledged the importance of the relationship between correctional officers and inmates. Some have said it is crucial to corrections work. It does, however, have its difficulties. As was explained to the Committee, correctional officers must interact with inmates who not only have complex problems, but often engage in problematic behaviours. Dr. Simpson said the following with respect to correctional officers: We often underestimate the magnitude of their task, especially when we’re trying to tell them to be rehabilitative as well when they’re in situations where there are people who have got their way through life using manipulation, menace, and standover tactics as the ways of getting the things they want in life [...].[69] Witnesses stated that front-line staff are increasingly using dynamic security, which focuses on positive interactions between officers and inmates. According to these witnesses, this form of security helps strengthen ties and encourages and motivates inmates to participate in their correctional programs. Witness Tony Van De Mortel, a correctional officer, who appeared as an individual, told the Committee that “the officers are the program.”[70] It was explained that, in certain institutions, officers provide counselling and are an integral part of the treatment team, which includes psychiatrists, psychologists and counsellors. The following quote summarizes what the Committee has heard, in that it recognizes the importance of the correctional work carried out by correctional officers, and also highlights the call for additional tools made by certain witnesses: Furthermore, I can’t underscore enough that while programs to deal with substance abuse and addictions are critical, front-line staff are the most significant and influential people in the life of inmates and stand to be the best source of positive behavioural change and demonstration of pro-social behaviour, and they must be provided with the tools, training, equipment, and support to keep illicit drugs and alcohol out of this environment in order to interact with limited barriers or fear for safety.[71] The Committee was also informed about what it considers a best practice at the Drumheller Institution in Alberta. A visual diagram representing inmates with their various criminal organization affiliations was developed and posted in the staff room. According to Mr. Mallette, this chart provides correctional officers with crucial information. Mr. Mallette also noted the absence of resources with respect to control towers and patrol vehicles. Given the complexity of their duties and the relationships they maintain with inmates, the Committee believes it is crucial for front-line staff to be supported in their jobs. The Committee learned from former correctional officer William Normington that, in CSC, “there is a lack of older, experienced personnel to guide and encourage young officers.”[72] The Committee feels that it would be worthwhile to assign experienced staff to mentor new recruits. The Committee heard that “[c]orrectional officers are little known and less appreciated by the vast majority of Canadians.”[73] The Committee believes that choosing a career or volunteering one’s time in corrections has positive impacts that directly affect Canadians. It also believes that it is necessary to recruit motivated candidates, dedicated to CSC’s objectives and mandate. They’ve got to continue to look for the best people. We always see on TV advertisements to join the military and the RCMP. I don’t live in Ontario, but perhaps it’s the OPP. When was the last time anybody saw an advertisement on TV advertising positions in a correctional facility? That’s one of the ways the standards can be raised.[74] During an appearance before the Committee, the Commissioner noted that correctional officers and security intelligence officers are receiving new training that focuses more heavily on dynamic security and the management of a complex prison population. The Committee is pleased to hear that officers are receiving more in-depth training in this area. Witness Jan Looman, Clinical Manager of the Regional Treatment Centre in Kingston, told the Committee that front-line staff also receive mental health training. The Committee agrees with the witnesses who stressed the importance of substance abuse training and hope that CSC will provide additional training to staff to help them better understand what substance abuse is and how to help inmates with substance abuse problems. Drugs and alcohol in correctional institutions pose a serious security problem. Mr. Van De Mortel spoke to the Committee about the physical and emotional scars he suffered following an incident where inmates had consumed homemade alcohol. Throughout our study, correctional officers spoke about the importance of eliminating drugs and alcohol from institutions. The Committee agrees with the witnesses that illicit substances undermine the relationship between officers and inmates, tie up CSC resources and destabilize the prison environment. The use of drugs and alcohol presents a serious security risk to our staff and to offenders themselves. It is a well-known fact that in Canada, as well as in other jurisdictions, much of the violence that occurs within institutional walls is directly related to drugs. Instances of violence destabilize our institutions and put my great staff at risk. This instability also limits our ability to manage a complex and diverse offender population, which in turn limits our ability to effectively prepare offenders to be released into society as productive, law-abiding citizens.[75] This is why the Committee hopes that CSC continues to recognize the importance of the day-to-day relationship between front-line staff and inmates to their correctional programs and rehabilitation. 4.3 RECOGNIZING THE IMPORTANCE OF EFFECTIVE AND TIMELY CORRECTIONAL PROGRAMS4.3.1 NEED FOR PROMPT INTAKE ASSESSMENTThe Committee heard that offenders sentenced to two years or more are first assessed to provide CSC with personal and administrative information about them. For example, CSC reviews the information provided by the courts regarding previous offences, as well as information about the offender’s family and level of education. A correctional plan is then prepared based on the criminogenic factors identified in the offender, who is then assigned correctional programs to promote rehabilitation. There was some concern expressed that these assessments occur within 90 days. Commissioner Head informed the Committee that: When a new inmate arrives at our federal penitentiaries they go through what we call an intake assessment process. During the first 90 days we subject an inmate to a variety of different assessments, including looking at the court documents that indicate the crime for which they’ve been sentenced. We look at the reasons the judge has sentenced the individual and the factors that were taken into consideration at the time of sentencing. Then we subject the inmate to a series of assessments that look at their social history and the various risk factors that contribute to criminality. That includes applying several tools to assess an individual's drug and alcohol substance dependency. That information gets rolled up over that period of time into what we call a correctional plan, which then becomes a road map for the inmate to follow during their period of incarceration. In a correctional plan, for example, if we’ve identified an individual as having a substance abuse problem or an alcohol problem, there would be an indication in the plan for them to be involved in one of our various substance abuse programs in the facility. [76] The Committee is also concerned about the growing number of inmates with mental health issues. Witnesses pointed out that these individuals have difficulty functioning in the prison environment and, given their mental health problems, are much more vulnerable among the general population. “Penitentiaries are stressful environments that make it difficult for these offenders to find and maintain any degree of stability.”[77] Treating these offenders is made even more difficult by the fact that they might also have substance abuse problems. The Committee shares the concerns raised and asks: RECOMMENDATION 5 That the Correctional Service of Canada continue to ensure that inmate assessment happens no longer than 90 days following their admission, so inmates can begin their correctional programs as quickly as possible. RECOMMENDATION 6 That the Correctional Service of Canada continue to ensure that mental health and addictions issues are assessed in a timely manner and that adequate and appropriate treatment be provided. The Committee learned from Jan Looman that offenders with mental health problems often have difficulty being admitted to CSC’s substance abuse program. However, the Committee was pleased to hear that in 2012 the Regional Treatment Centre in Kingston will offer a modified version of the substance abuse program for inmates with mental health issues. Before the Committee, Commissioner Head also noted: [T]that as a result of our transformation agenda and strategic reinvestment, we have invested over $30 million more towards programming in the past three years. The vast majority of these funds were dedicated to hiring more staff to deliver programs to our offender population.[78] Consequently: RECOMMENDATION 7 The Committee takes note of the progress that this Government has made in addressing issues of mental health in prison and the link between offenders with mental health issues and substance abuse in prison. 4.3.2 THE CORRECTIONAL SERVICE OF CANADA’S CURRENT CORRECTIONAL PROGRAMMINGThe Committee recognizes, as did all of the witnesses, that CSC’s substance abuse programs are known the world over and serve as models for many countries, including the United Kingdom, Norway and Sweden. An independent evaluation showed that dependency and recidivism decreased among inmates who had completed the substance abuse program. Research shows that offenders who participate in substance abuse programs are 4.5 times more likely to earn discretionary release, 45% less likely to be re-incarcerated because of a new offence, and 63% less likely to return with a new violent offence.[79] The completion rate for CSC’s substance abuse programs is high, ranging from 83% to 85%, whereas the average for other correctional programs is about 70%. The Committee was informed, however, that 20% of inmates refuse to participate in their correctional program[80]. The Committee shares the concern about program waiting lists that was voiced by several witnesses[81]. It was made clear to the Committee that inmates are placed on waiting lists according to the severity of their problems and needs and their parole date. The Committee also acknowledges the fact that CSC has managed to reduce waiting times for correctional programs by half over the past three years. The Committee also heard that most inmates genuinely want to take part in correctional programs, yet fewer than 15% of offenders attend a basic correctional program every day.[82] The Committee is encouraged by the implementation of the Integrated Correctional Program Model (ICPM). The evidence suggests that this pilot project, which has already been implemented in the Pacific and Atlantic regions, enables inmates to begin their correctional programming within 45 days following the start of their sentence rather than 150 to 250 days, as was the case in the past. The Office of the Correctional Investigator expressed concern regarding the ICPM. The ICPM collapsed three programs that used to take a year and a half to complete into one six‑month program. The Office of the Correctional Investigator pointed out that the program has not yet been evaluated and that “the program delivery, style, and content has not been validated.”[83] The evidence suggests also that CSC is, unfortunately, having to contend with staff retention and recruitment problems. The Commissioner told the Committee that, despite the resources it has obtained over the past several years, CSC needs more program officers in order to deliver its programming. It was explained that there is also a shortage of psychologists and correctionnal officers.[84] The Office of the Correctional Investigator named other factors that limit access to correctional programming, such as the lack of physical capacity to deliver programs. The point was corroborated by other witnesses who fear the effects of an increase in the number of inmates. I am a little worried with the direction things are going in now, and particularly the notion that the overcrowding is going to undo a lot of the excellent programming and supports that had been available through our corrections system. And some of the legislative amendments that are being proposed I don’t think will, shall we say, increase our international stature in the area of corrections.[85] Consequently, the Committee recommends: RECOMMENDATION 8 That every effort be taken to eliminate waiting lists so that inmates may receive speedy access to programs, especially drug and alcohol treatment programs, as quickly as possible. 4.4 RECOGNIZING THE IMPORTANCE OF A PRISON ENVIRONMENT THAT FOSTERS THE REHABILITATION OF INMATESDuring our study, several witnesses pointed out the importance of creating a stable prison environment that is safe for the people who work and live there. The consensus is that full rehabilitation of inmates is equally essential to public safety. A number of witnesses made the point that the presence of drugs and alcohol in prisons makes it harder to manage correctional programs. CSC’s zero tolerance policy has been in force since 2007. However, drugs always find their way into prison. The witnesses we heard have very different positions on the policy and the measures taken by CSC. For some, CSC’s objective is somewhat unrealistic; however, the majority of the witnesses agreed that this objective is imperative in the circumstances because half measures would do even greater harm. To complement its zero tolerance policy, CSC adopted the Transformation Agenda to get all illegal drugs out of prisons. The strategy uses a three-pronged approach: prevention, treatment and interdiction. In 2008, after the National Drug Strategy and the Transformation Agenda were put in place, CSC was given $122 million over five years to help it meet its objectives. The Commissioner stated that those funds will enable CSC to take a more rigorous approach that focuses on the interdiction aspect. Other witnesses pointed out that a balanced approach that fosters combined efforts on the reduction of supply, the reduction of demand and the reduction of adverse impact would be more feasible[86]. Proponents of a rigorous approachProponents of this approach told the Committee that the decrease in the percentage of positive urinalysis results and the decrease in the proportion of offenders who refuse to provide a sample show that the measures CSC has taken have been successful. The Commissioner added that he believes the number of offenders who die of an overdose has decreased and the number of drug seizures has increased. A number of witnesses observed that there are still improvements that can be made to the prison environment so that inmates who are motivated to change their behaviour can have a better chance of healing and being rehabilitated. [O]ver the years I have seen a dramatic change in how CSC is meeting this challenge head-on. I have provided you with just a few examples here. In my area, the increase in our security intelligence capacity, as well as the introduction of new technology and the establishment of positive working relationships within the intelligence community, have all proven that we are definitely moving in the right direction.[87] Proponents of a balanced approachOn the subject of increased funding for interdiction efforts, several witnesses drew attention to the inexplicable lack of funding for correctional programming. The Office of the Correctional Investigator made the point that a comprehensive drug strategy must be accompanied by a series of measures, namely prevention, treatment, harm reduction and interdiction. The majority of the witnesses who advocate a balanced approach also pointed out the importance of considering inmate health a public health issue. Interaction with family and outside contacts is encouraged and often beneficial to the inmates and to their overall health, rehabilitation and successful reintegration. However the Committee agrees with testimony that reasonable interdiction techniques remain in place so that visitors are unable to bring into the institutions unauthorized items, contraband or illegal substances. The Committee recognizes that pressure to introduce drugs into the institution can come from criminal organizations or dealers in the community and that interdiction strategies that are reasonable can alleviate those pressures on inmates and visitors and improve institutional safety. The Committee understands that some visitors can feel intimidated or embarrassed by the nature of certain interdiction measures and encourages reasonable use of these techniques to balance the security needs of the institution, staff, inmates and visitors with the important function visits play in successful reintegration and long-term community safety. The Committee believes it is essential that CSC continue its efforts and concurs with all of the witnesses who recommended a tougher approach with respect to interdiction measures. Consequently, the Committee recommends: RECOMMENDATION 9 That the Government maintain its commitment to establish drug-free prisons. RECOMMENDATION 10 That the Correctional Service of Canada continue to undertake and implement new security and interdiction measures at federal penitentiaries. RECOMMENDATION 11 The Committee recognizes that problems with drugs and alcohol are still prevalent in Canadian prisons and that strong interdiction measures and effective programming implemented by the Correctional Service of Canada drastically reduce these problems. We call on the Government to continue their already substantial progress in this area. 4.5 RECOGNIZING THE IMPORTANCE OF INCREASING THE CHANCES OF SUCCESS OF OFFENDERS RELEASED INTO THE COMMUNITYMost federal offenders serve only part of their sentence in a penitentiary. The other part is served under supervision in the community. The Committee unanimously agrees that rehabilitation and treatment are key elements in the correctional system and that it is essential that treatment provided in a correctional facility be carried over into the community. It is nevertheless troubling to find that inmates’ individual needs have become more complicated in recent years.[88] Rob Sampson, former chair of the Correctional Service of Canada’s Outside Review Board, told the Committee that the average sentence is three and a half years. Mr. Sampson stated that, given the complicated nature of inmates’ specific problems and the length of an average sentence, it is extremely difficult for CSC to fully rehabilitate these individuals, although that is the objective. Other witnesses pointed out that individuals with addiction problems usually struggle with those problems their entire lives. How is it humanly possible to get somebody who I just described—with a grade eight education, unemployable, addicted to drugs, with severe family problems—resolved after three years? It’s just not possible.[89] The Committee underscores the importance of ongoing support in the community. We believe that continuity of service is essential in mitigating the risk of reoffending. CSC ensures the employability of inmates through a special service called CORCAN. CSC witnesses told the Committee that the process begins long before an inmate is released and that by the time he or she is paroled, an inmate is well prepared to hold a job in the community. Ross Toller, Deputy Commissioner, Transformation and Renewal Team, Correctional Service Canada, had the following to say on the subject: The employment area is one of our highly focused areas in terms of assessment when inmates first come in, looking at what are their employment skills capability and what is their past employment record. A lot of research shows, exactly as you heard from inmates, that lack of employment does contribute to their crime cycle. We look at building skills, as Mr. Wheeler has mentioned. More recently, we’ve been looking at a focus through our transformation agenda to give employability skills that are more job-market-oriented, based on some of the material that we see through job availability markets. If I can just give you a couple of examples, knowing that some of the vocational trade area is going to have a need in future years for Canada as a whole, we partnered with a number of groups and community colleges to give the requisite training that provides the skill sets to inmates. They learn, by way of this example, carpentry skills that are certifiable skills that will apply towards their ability. In some cases we’ve had success where we’ve been building a framework for areas of housing and employers that we partner with on the inside hire our offenders on the outside. More recently, in a couple of examples, we’ve partnered with some aboriginal communities where we provide the skills from our end and then build housing in aboriginal communities, where inmates are giving back to the community. That’s just one example where we focus on the employability for exactly the point that you’ve raised. And I believe you heard from inmates that this carries itself into the community as well.[90] Inmates interviewed at Collins Bay and Joyceville also pointed out the importance of having job opportunities and stated that inmates who are unemployed often end up reoffending. The inmates told the Committee that despite CSC’s efforts to provide them with job skills, many inmates do not find work. They added that too many employers refuse to hire former inmates. The Committee was disappointed to learn from witness Pierre Mallette that occupational training for inmates is not available in all institutions and believes that this is an impediment to the full rehabilitation of inmates in the community. It further believes that the transition from prison to the outside has to be gradual. For that reason, the Committee underscores the importance of parole officers in the reintegration process. In the members’ view, proper training is crucial to an inmate’s chances for success. Consequently, the Committee asks CSC to ensure: RECOMMENDATION 12 That professional training programs and increased work opportunities be offered for inmates. RECOMMENDATION 13 That measures be taken to ensure that new parolees are adequately supported to continue their rehabilitation and reintegration in the community. The witnesses made repeated reference to the importance of inmates maintaining links with their family and the community.[91] CSC also encourages inmates to restore broken relationships in order to reduce the negative impact of incarceration on family relations and, by extension, on inmates themselves. An inmate’s contact with the community creates a support network, facilitates social reintegration and minimizes the risk of the inmate reoffending. Inmates who are able to remain connected to their family, friends and community are motivated to pursue and attain the objectives set out in their correctional plan. Consequently, the Committee recommends: RECOMMENDATION 14 That the Correctional Service of Canada take steps to encourage positive and healthy family visits. CONCLUSIONThe recommendations made in this report highlight the significant progress CSC has made to date and seek to encourage those who work in corrections. Furthermore, the Committee hopes that CSC will benefit from its recommendations, which lay the foundation for better management of an increasingly complex and diverse prison population. Finally, the Committee hopes that CSC will meet its objectives for the rehabilitation of federal offenders who are struggling with substance abuse issues. [1] Correctional Service Canada, Commissioner’s Directive No. 585, National Drug Strategy, 2007, http://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/text/plcy/cdshtm/585-cde-eng.shtml. [2] Motion adopted by the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security on 27 September 2011. [3] A list of witnesses will be found in Appendix A, and a list of briefs in Appendix B. [4] Howard Sapers, Correctional Investigator, Office of the Correctional Investigator, Evidence, 6 October 2011. [5] Pierre Mallette, National President, Union of Canadian Correctional Officers, Evidence, 29 September 2011. [6] See the Correctional Service of Canada Institutional Drug Sub-Culture Model at Appendix C. [7] Kenneth Putnam, as an individual, Evidence, 1 November 2011. [8] Don Head, Commissioner, Correctional Service Canada, Evidence, 1 December 2011. [9] Pierre Mallette, Evidence, 29 September 2011. [10] The Correctional Investigator told the Committee that 50 grams of tobacco, valued at between $18 and $20, has an institutional value of between $300 and $500. Evidence, 6 December 2011. [11] Evidence, 29 September 2011. [12] Ibid. [13] According to Commissioner Don Head, inmates who had gang affiliations prior to their incarceration were most often members of street gangs. He said that there are now more street gang members than there are members of biker gangs or those with ties to traditional organized crime. Evidence, 20 October 2011. [14] Ibid. [15] Commissioner’s Directive No. 860, Inmate’s Money, 2011, states that each inmate is encouraged to budget so that funds are available for conditional release and for ongoing expenses (e.g., canteen and personal property purchases, telephone calls). As well, this policy is intended to control the flow of money so as to ensure the safety of persons and the security of the penitentiary. Inmates are allowed to have two bank accounts: a current account and a savings account. Pay earned from employment is deposited in the inmate’s current account. [16] According to Commissioner’s Directive No 890, Inmate’s Canteen, 1998, inmates manage and operate canteens under the supervision of the Regional Deputy Commissioner, and the position of Inmate Canteen Operator is included in the CSC employment program. [17] Ivan Zinger, Executive Director and General Counsel, Office of the Correctional Investigator, Evidence, 6 October 2011. [18] Evidence, 29 September 2011. [19] Andrea Markowski, Warden, Edmonton Institution for Women, Correctional Service Canada, Evidence, 27 October 2011. [20] Don Head, Evidence, 29 September 2011. [21] Dr. Sandy Simpson, Clinical Director, Law and Mental Health Program, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Evidence, 18 October 2011. [22] Ibid. [23] Don Head, Evidence, 29 September 2011. [24] Evidence, 8 December 2011. [25] Ibid. [26] Correctional Service Canada, FORUM on Corrections Research – Development of an Aboriginal Offender Substance Abuse Program, available at http://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/text/pblct/forum/e181/e181j-eng.shtml. [27] Andrea Markowski, Evidence, 27 October 2011. [28] Don Head, Evidence, 29 September 2011. [29] Kevin Snedden, Acting Assistant Deputy Commissioner, Corporate Services (Ontario), Correctional Service Canada, Evidence, 6 October 2011. [30] Catherine Latimer, Executive Director, John Howard Society of Canada, Evidence, 4 October 2011. [31] Eleanor Clitheroe, Chief Executive Officer, Prison Fellowship Canada, Evidence, 4 October 2011. [32] Howard Sapers, Evidence, 6 October 2011. [33] Correctional Service Canada, 2010-2011 Departmental Performance Report. http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/dpr-rmr/2010-2011/inst/pen/pen00-eng.asp. [34] CSC was responsible for 13,287 federally incarcerated offenders in 2008-2009, compared with 13,500 in 2009-2010. [35] “The Tackling Violent Crime Act (C-2) is expected to result in an increase of nearly 400 male offenders by 2014, and the Truth in Sentencing Act (C-25) is projected to bring … more than 3,000 men and nearly 200 women, by March 31, 2013.” Correctional Service Canada, 2011-2012 Report on Plans and Prioritiesttp://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/rpp/2011-2012/inst/pen/penpr-eng.asp?format=print. [36] See sections 76, 77 and 80 of the Act. [37] Ivan Zinger, Evidence, 6 December 2011. [38] Ross Toller, Deputy Commissioner, Transformation and Renewal Team, Correctional Service of Canada, Evidence, 6 December 2011. [39] Correctional Service Canada, About CORCAN, 4 August 2009. [40] Corrections and Conditional Release Act, ss. 46 – 67. [41] Corrections and Conditional Release Act, s. 38. [42] Corrections and Conditional Release Act, ss. 40(i), (k), and (l). Contraband is defined in section 2 of the Act, and includes “an intoxicant.” [43] Corrections and Conditional Release Act, s. 45. [44] Ross Toller, Evidence, 6 December 2011. [45] Don Head, Evidence, 20 October 2011. [46] Correctional Service Canada, Commissioner’s Directive 566-13, Detector Dog Program, 28 April 2011, http://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/text/plcy/cdshtm/566-13-cd-eng.shtml. [47] Howard Sapers, Evidence, 6 December 2011. [48] Kim Pate, Executive Director, Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies, Evidence, 4 October 2011. [49] Don Head, Evidence, 1 December 2011. [50] Don Head, Evidence, 29 September 2011. [51] Ibid. [52] Correctional Service Canada, 2010-2011 Departmental Performance Report. [53] Ibid. [54] Howard Sapers, Evidence, 6 October 2011. [55] Correctional Service Canada, Correctional Program Descriptions, June 2009. [56] Pierre Mallette, Evidence, 29 September 2011. [57] Evidence, 6 October 2011. [58] Corrections and Conditional Release Regulations, s. 102; Correctional Service Canada, Progress against the Correctional Plan, Commissioner’s Directive 710-1, 18 September 2007, http://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/text/plcy/cdshtm/710-1-cd-eng.shtml. [59] Correctional Service Canada, Commissioner’s Directive No. 585, National Drug Strategy, 2007, http://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/text/plcy/cdshtm/585-cde-eng.shtml. [60] See for example the evidence of Rob Sampson, as an individual, Evidence, 4 October 2011. [61] Evidence, 29 September 2011. [62] Ibid. [63] Don Head, Evidence, 29 September 2011; Corrections and Conditional Release Act, ss. 38 – 44. [64] Pierre Mallette, Evidence, 29 September 2011. [65] Evidence, 29 September 2011. [66] Ibid. [67] Christer McLauchlan, Security Intelligence Officer, Stony Mountain Institution, Evidence, 1 December 2011. [68] Don Head, Evidence, 1 December 2011. [69] Sandy Simpson, Evidence, 18 October 2011. [70] Tony Van De Mortel, as an individual, Evidence, 1 November 2011. [71] Ibid. [72] William Normington, as an individual, Evidence, 6 October 2011. [73] Kenneth Putnam, Evidence, 1 November 2011. [74] Ibid. [75] Don Head, Evidence, 29 September 2011. [76] Evidence, 29 September 2011. [77] Jan Looman, Clinical Manager, Regional Treatment Centre, Kingston, Ontario, Correctional Service Canada, Evidence, 8 December 2011. [78] Don Head, Evidence, 1 December 2011. [79] Ross Toller, Evidence, 6 December 2011. [80] Don Head, Evidence, 29 September 2011. [81] See for example the evidence of Kim Pate, Evidence, 4 October 2011 and Eleanor Clitheroe, Evidence, 4 October 2011. [82] Howard Sapers, Evidence, 6 December 2011. [83] Ibid. [84] Howard Sapers, Evidence, 6 October 2011. [85] Catherine Latimer, Evidence, 4 October 2011. [86] See for example the evidence of Catherine Latimer, Evidence, 4 October 2011 and Howard Sapers, Evidence 6 October 2011. [87] Kevin Snedden, Evidence, 6 October 2011. [88] Rob Sampson, Evidence, 4 October 2011. [89] Ibid. [90] Ross Toller, Evidence, 6 December 2011. [91] See for example the evidence of Catherine Latimer, Evidence, 4 October 2011 and Wayne Skinner, Deputy Clinical Director, Addictions Program, Centre for Addiction and Mental Heealth, Evidence, 18 October 2011. |