FAAE Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

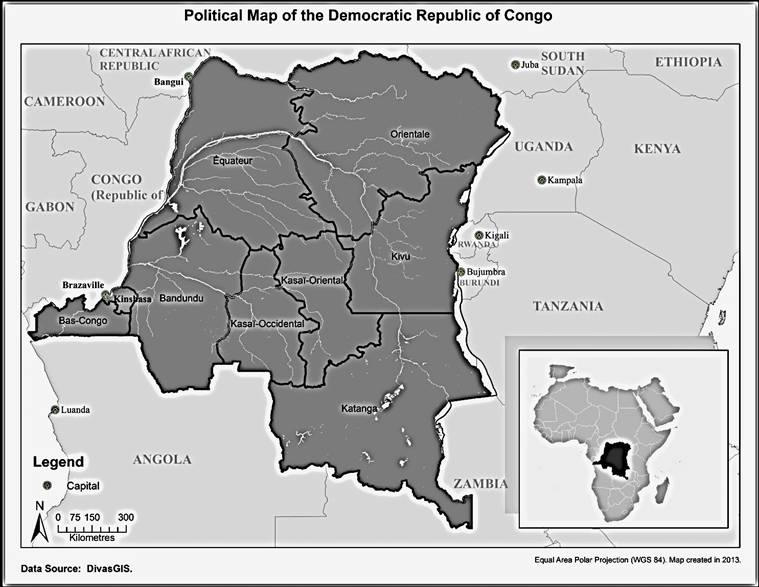

CHAPTER 2: CASE STUDY OF SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGOThe DRC is located in central Africa, stretching from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the African Great Lakes in the west. The country has a population of approximately 75.5 million, comprising over 200 ethnic groups.[41] The main religious groups are Roman Catholic (50%), Protestant (20%), Kimbanguist (10%) and Muslim (10%).[42] The country has an area of 2,345,410 square kilometres, which is roughly the size of Ontario and Quebec combined. The eastern regions of the country, particularly North and South Kivu provinces, are rich in mineral resources (primarily copper, cobalt, gold, diamonds, coltan, zinc, tin and tungsten). The mining sector is the most important source of export income, with base metals and diamonds accounting for 86% of the nation’s exports in 2012.[43] Figure 1

In 2013, DRC ranked 186th among the 187 countries on the United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) Human Development Index, which is measured on the basis of three basic dimensions of human development: health, education and income.[44] In 2009, only 56.6% of women over the age of 15 were literate, compared with 77.4% of men.[45] A. Overview of armed conflict and insecurity in the DRCSince the early 1990s, the Great Lakes region of central Africa, which includes the eastern DRC, Rwanda, Burundi and Uganda, has experienced a high degree of instability due to a variety of armed conflicts within and between states, as well as difficult transitions toward more democratic governance. At its peak, between 1997 and 2001, the armed conflict in the DRC was described as the widest interstate war in modern African history.[46] Jillian Stirk, then Assistant Deputy Minister, Europe, Eurasia and Africa Bureau at the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada (DFATD) (formerly the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade),[47] summarized the deleterious impact that multiple years of conflict and instability have had on the country: The DRC has a history blighted by tragedy, first under colonial rule, then followed by the brutal regime of President Mobutu, who ruled for over 30 years. Regional wars, including the 1994 Rwandan genocide as well as the 1997–2003 first and second Congo wars, which involved armies from eight neighbouring countries, have undermined the social and political fabric of the region. Together these events resulted in approximately five million deaths from murder, famine, and disease. Millions were displaced, economies were devastated, governance structures collapsed, and armed groups became increasingly powerful. Corruption is a fact of life.[48] Although the intensity of armed conflict in the DRC as a whole has ebbed and flowed since 1996, the eastern DRC has been the epicentre of much of this violence and instability. A number of non-state armed groups, some of whom are Congolese and some of whom have links to foreign governments (in particular, Rwanda and Uganda), have continued to operate and launch attacks in the north-eastern and eastern parts of the country, where government forces have been unable to maintain effective control.[49] In particular, armed conflict and violence have been endemic in Ituri District and parts of Haut and Bas Ulélé districts in Orientale Province, the provinces of North and South Kivu and parts of Katanga Province. 1. History of the ConflictIn 1994, an estimated one million Rwandese Hutu refugees — including Hutu militia forces (known as the Interahamwe) who had participated in the Rwandan genocide — fled to the neighbouring North and South Kivu regions of eastern DRC (then known as Zaire). Once there, the Rwandan militias made up of ethnic Hutus started using the territory as a base for incursions against Rwanda, further destabilizing a region already troubled by ethnic and inter-communal tensions by drawing Rwanda into armed conflict in the Kivu regions. By 1996, the Hutu militias also began attacking Zaire’s members of the Tutsi ethnic group that had historically resided in the country, as well as Tutsis recently displaced by the genocide in Rwanda. Ethnic Tutsis in Zaire reacted to this threat by organising their own armed groups, many of which benefitted from Rwandan support. Political opponents of President Mobutu quickly joined forces with the Tutsi militias in a coalition led by Laurent-Desiré Kabila, who was himself supported by Uganda and Rwanda. Laurent Kabila’s forces took Kinshasa in 1997, after which he declared himself president and renamed the country the Democratic Republic of theCongo (DRC). As noted by Ms. Stirk, this period of conflict in 1996–1997 is called the First Congo War.[50] Instability and violence continued in the eastern DRC and rebellion broke out against Laurent Kabila’s government in 1998. Different armed groups in the resource-rich Kivu regions, who were backed by Rwanda and Uganda, eventually took control of significant portions of the northern and eastern parts of the country. President Kabila received support from the armed forces of Zimbabwe, Namibia and Angola to counter this threat. At different times during the conflict, Sudan, Chad and Burundi were also involved in the fighting. This regional phase of the conflict is called the Second Congo War, which lasted from 1998 to 2003. In July 1999, the governments of the DRC, Angola, Namibia, Rwanda, Uganda and Zimbabwe, and representatives from the two largest rebel groups signed a ceasefire agreement in Lusaka, Zambia.[51] Pursuant to this agreement, the UN Security Council approved the deployment of the United Nations Organization Mission in the DRC (known by its French acronym MONUC) in November 1999 to support the implementation of the Lusaka ceasefire agreement, facilitate humanitarian assistance and assist in the protection of human rights.[52] In 2001, President Laurent Kabila was assassinated and his son, Joseph, took power. Fighting resumed in the eastern parts of the country in 2002, involving various ethnic militias and armed groups, as well as troops from Rwanda and Uganda. Peace talks in Sun City, South Africa, brought an end to the fighting the same year and allowed Joseph Kabila to lead a transitional government in 2003; soon after, most foreign troops began to withdraw, bringing large-scale regional conflict to an end.[53] Following the end of this stage of the conflict, over 96,000 rebel fighters were demobilized and more than 50,000 were integrated into the Congolese national army between 2003 and 2006.[54] A new constitution was approved in a national referendum in December 2005 and elections were held in 2006 — the first free elections held in the country since 1960. The presidential elections were won by the incumbent president, Joseph Kabila, who received 58% of the vote in an election that was generally considered to be free and fair.[55] Despite the fact that many parts of the country began to stabilize and focus on post-conflict reconstruction and development, another round of fighting between rebels and government forces in eastern DRC began in late 2006 and continued until peace agreements were signed with some — but not all — of the militia groups in January 2008. On 23 March 2009, the government of the DRC reached a peace agreement with one of the most important Tutsi militias, the Congrès National Pour la Défense du Peuple (the National Congress for the Defence of the People, known by its French acronym, CNDP). Under the peace agreement, CNDP fighters would be integrated into the Congolese military, which is known by its French acronym FARDC (Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo).[56] In January 2009, the governments of Rwanda and the DRC began cooperating in an offensive against Hutu rebel groups in the eastern DRC that had not signed ceasefire agreements, including, most importantly, the Forces démocratiques de libération de Rwanda (Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda, known by its French acronym FDLR).[57] In addition, the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), an armed group originating in Uganda, took advantage of the instability in the DRC and moved into Orientale Province, in the north-eastern part of the country, between 2005 and 2007. The LRA began launching attacks against villages in neighbouring countries and, later, against the Congolese population (particularly in the Haut and Bas Ulélé districts). The group’s capacity has been reduced — but not destroyed — by military offensives involving troops from Uganda and the DRC that began in late 2008.[58] In 2005, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued arrest warrants for high-ranking members of the LRA, including its leader, Joseph Kony, but to date they have evaded capture.[59] a. Conflict and Instability Since 2009Overall, while peace-building efforts intensified during this period, insecurity and attacks on civilians by various armed actors remained a feature of life in the country’s eastern regions, where conflict-related sexual violence continued to be reported.[60] In November 2011, the DRC held a general election marred by violence, a lack of transparency, irregularities and human rights violations. Incumbent President Joseph Kabila remained in power following the election. Ms. Malikail informed the Subcommittee that “[a]rmed groups and elements of the armed forces actively promoted the election of certain presidential candidates and members of Parliament through fear and intimidation. … The outcome of the elections and the increase in political tension and instability … had a negative impact on the security situation in the DRC.”[61] According to witnesses, the post-election period saw the closing of democratic space in the country.[62] Throughout 2012 and most of 2013, fighting and attacks on civilians in the eastern DRC intensified,[63] in particular as a result of renewed conflict between the Congolese army and a non-state armed group called the Mouvement du 23 mars (Movement of March 23rd, known as M23). Sexual violence by both rebel fighters and Congolese government forces continued to be a feature of this round of conflict.[64] M23 is made up primarily of former CNDP fighters who mutinied after having been integrated into the Congolese army following the 23 March 2009 peace agreement noted above. The rebels claimed that they mutinied because they believed the Congolese government was not living up to commitments it made in the agreement.[65] It has been reported that M23 received support from the governments of Rwanda and Uganda.[66] For 11 days in December 2012, following battles with the Congolese military, M23 took control of Goma, the largest city in the conflict-torn North and South Kivu provinces and the headquarters of UN peacekeeping operations. In March 2013, infighting within M23 caused a faction of the movement, led by Bosco Ntaganda, to flee the DRC. Mr. Ntaganda subsequently surrendered himself to the U.S. Embassy in Rwanda. He was later transferred voluntarily to the ICC to face charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity — including counts alleging responsibility for rape and sexual slavery committed in Ituri district in 2002 and 2003.[67] M23 was defeated militarily by UN forces and the FARDC in late October and early November 2013.[68] In mid-December 2013 in Nairobi, Kenya, the Government of the DRC and M23 reached a formal agreement to end the rebellion.[69] Notably, while the declarations provide for amnesty to M23 fighters for acts of war and insurrection, crimes of sexual violence as well as other war crimes and crimes against humanity are excluded from the scope of the amnesty. Despite the end of the M23 rebellion, the security situation in the eastern DRC remains fluid and other armed groups reportedly continue to use sexual violence as a weapon against civilians.[70] Figure 2

The Subcommittee was told that several complex and inter-related factors explain the continued fighting between government forces and various armed groups in the eastern DRC. According to Patricia Malikail, Director General, Africa Bureau at DFATD, “[k]ey motivators for violence originate from the competition for resources, political grievances based on ethnicity and land ownership, as well as from fear between ethnic groups — for example, fear of the increasing influence of the Rwandaphone community.”[71] Ongoing regional instability exacerbates the violence and facilitates the incursion of non-state armed groups across the DRC’s porous borders.[72] According to witnesses, sexual violence has been a dominant feature of all stages of the conflicts. In interviews conducted by a high-level panel convened by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights on remedies and reparations for victims of sexual violence in the DRC, survivors of sexual violence in the North and South Kivu regions considered the restoration of peace and security to be a precondition to any type of return to normal life. Peace is also their number one priority — their “big dream,” “first prayer” and “greatest hope”.[73] 2. UN Peacekeeping Missions in the DRCUN peacekeeping missions in the DRC — first MONUC and then, from 1 July 2010, the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the DR Congo, known by the acronym MONUSCO[74] — have had mixed success to date in protecting civilians from violence in the eastern provinces and in addressing the high prevalence of sexual violence in those areas, at least in part due to severe capacity constraints.[75] The Subcommittee was told that in 2004–2005, it was reported that members of MONUC were involved in the sexual exploitation and abuse of Congolese women and girls.[76] To find out how the situation has changed since that time, the Subcommittee consulted the UN Secretary-General’s 2013 report on Special measures for protection from sexual exploitation and sexual abuse. Although the situation has clearly improved since 2004–2005, the report indicates that MONUSCO “consistently” experienced the highest number of reported allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse amongst UN peace missions.[77] A recent evaluation of the mission by UN Women concluded that it continues to face challenges in terms of investigating and preventing such conduct.[78] In March 2013, responding to a perceived need for more effective and robust UN action to protect civilians in the context of continued conflict in the eastern DRC, the United Nations Security Council authorized the creation of an intervention brigade empowered to conduct offensive combat missions, under the command of the MONUSCO Force Commander. The brigade was given a mandate to neutralize, prevent the expansion of and disarm foreign and Congolese armed groups and contribute “to reducing the threat posed by armed groups to state authority and civilian security in the eastern DRC and to make space for stabilization activities.”[79] The brigade was part of the successful offensive against M23 rebels. It then began operations against the FDLR militia.[80] The Subcommittee hopes that renewed UN efforts in eastern DRC, combined with the intensification of efforts to combat sexual violence within UN operations, will have a positive impact on the security situation. The Subcommittee believes it is vital that the effective protection of civilians, including their protection from sexual violence by all perpetrators — including peacekeepers and UN staff — be a top priority for international and Congolese action in the eastern DRC. B. The nature of conflict-related sexual violence in the DRCSexual violence against women and girls in armed conflict began to increase dramatically during the First Congo War, when “rape as a weapon of war proved to be extraordinarily effective” at demoralizing the population and breaking down the structure of communities.[81] The Subcommittee was told that widespread sexual violence has been used to terrorize entire groups in order to displace large numbers of people, who must then take refuge in camps or elsewhere, facilitating armed actors’ control over a particular territory or population.[82] In the DRC, sexual violence has also been employed as a means to attack individuals of a particular ethnicity and reportedly is used as a form of ethnic cleansing.[83] The Subcommittee wishes to stress once again that international law absolutely prohibits these types of deliberate attacks on civilians.[84] According to the witnesses who appeared as part of this study, conflict-related sexual violence in the DRC is particularly brutal in nature. The violence spares no one — women and men, girls and boys, babies and grandparents have all been raped and, often, intentionally mutilated.[85] As Nicole Mwaka from the Congo Yetu Initiative informed the Subcommittee, “[t]he intent is to destroy, to damage, to humiliate. They want to leave their mark, impose their decisions, show that they are stronger.”[86] Ms. Coutu, from the Centre for Peace Missions and Humanitarian Studies at the Raoul-Dandurand Chair of Strategic and Diplomatic Studies at the University of Quebec in Montreal, explained that rapes frequently are planned in advance and occur in public areas, on roads or in fields, in view of the family and community. In this way, armed groups use sexual violence as a weapon to control and humiliate victims, punish communities for their political loyalties and establish a climate of terror.[87] Armed groups also abduct women and girls in order to keep them as sex slaves or forcibly marry them to fighters. This practice is particularly common amongst the LRA, an armed group led by Joseph Kony with roots in Uganda. Despite having been indicted by the ICC, Kony and his group continue to attack villages in order to loot supplies in the northeastern part of the DRC, in areas bordering the Central African Republic and South Sudan. During their raids, LRA fighters typically abduct adults and children to carry the pillaged goods. Most of the captured women and girls are forced into sexual servitude and, in some cases, are forced to marry LRA commanders.[88] During its 2012–2013 mutiny, the M23 militia also reportedly forced young girls to act as “wives” to commanders; other militias also reportedly have held women and girls as sex slaves.[89] Research conducted by the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative’s Women in War program points to the existence of specific attitudes and practices within armed groups that promote sexual violence against civilians. For instance, Ms. Jocelyn Kelly, the program’s director, told the Subcommittee that extremely violent initiation practices in one particular armed group led to a sense of dehumanization amongst fighters. Fighters may also believe that they are entitled to take what they want from civilian populations, including sex, to compensate for the sacrifices they have made defending their country (which is how they perceive their role). At the same time, Ms. Kelly said that many rebel commanders have no interest in trying to prevent rape by their fighters. Some commanders see sexual violence as a way for fighters to control civilian populations; others either condone or overlook it.[90] Witnesses indicated that both fighters with non-state armed groups and soldiers of the FARDC are credibly suspected of committing crimes of sexual violence in the DRC.[91] While most acts of sexual violence in the DRC in conflict zones can be attributed to fighters or soldiers, there has also been a worrying rise in the number of civilian perpetrators.[92] The Subcommittee is concerned that the increase in civilian perpetrators could indicate that sexual violence is becoming normalized in the eastern DRC, a trend that could prevent women and girls from fully participating in the rebuilding of their society if a durable peace is ever achieved.[93] 1. The Extent of Sexual Violence in Conflict Zones of the DRCWitnesses stressed to the Subcommittee that sexual violence is being committed on a massive scale in the DRC. Ms. Béatrice Vaugrante, from the Canadian Francophone Section of Amnesty International, said, “[t]he acts of sexual violence committed in the DRC are sometimes described as a war within a war.” In fact, Ms. Kristin Kalla, Senior Program Officer at the Trust Fund for Victims (TFV) of the ICC, told the Subcommittee that “sexual violence has been found to be the most common form of violence and the most widespread form of criminality” in the country.[94] According to witness testimony, however, most statistical estimates are likely to underestimate the prevalence of sexual violence, and, in particular, conflict-related sexual violence in the DRC. Ms. Coutu informed the Subcommittee that many women do not report incidents of sexual violence to the police, often because they wish to avoid the stigma associated with being a victim of this type of crime. Moreover, only a small proportion of women seek medical treatment after being attacked, which means that hospital records cannot provide an accurate indication of the number of victims.[95] Witnesses stressed that concerns regarding under-reporting apply equally, if not more so, to male victims of conflict-related sexual violence.[96] In order to get a better grasp of the magnitude of sexual violence in the DRC, the Subcommittee consulted two recent public health studies.[97] A June 2011 study published in the American Journal of Public Health used data-gathering techniques designed to avoid under-reporting.[98] The study found that “estimates of rape among women aged 15 to 49 years in the 12 months prior to the [2007 DRC Demographic and Health] survey translate into approximately 1,150 women raped every day, 48 women raped every hour, and 4 women raped every 5 minutes” throughout the DRC.[99] The total female population in the relevant age range was 14,754,551. The study noted that these estimates are “several orders of magnitude higher than what has been cited in previous studies” and confirmed that rates of sexual violence were particularly high in eastern regions of the country affected by armed conflict.[100] The second study consulted by the Subcommittee represents one of the few attempts to quantify conflict-related sexual violence against both men and women. Researchers conducted the population survey of 998 adults in the eastern DRC over a four-week period in March 2010 and published the results in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Of respondents in the study, 29.9% of women and 22% of men reported having been the victim of some form of conflict-related sexual violence over the previous 16 years. Both men and women reported being forced into sexual servitude by a person associated with an armed group. In addition, both men and women were reported to have been the perpetrators of conflict-related sexual violence.[101] 2. The Impact of Sexual Violence on Individuals, Families and CommunitiesWitnesses emphasized that sexual violence used as a weapon of war has had a profound and an extended impact on the physical and psychological health of many Congolese people, as well as on their communities, society and economy. The physical repercussions of sexual violence vary and include severed and broken limbs, burned and/or mutilated flesh, fistulas,[102] sexually transmitted infections — including HIV/AIDS — unwanted pregnancy, long-term urinary incontinence, infertility and death.[103] Victims’ lack of access to adequate medical care often aggravates the physical injuries associated with sexual violence. For example, the 2010 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, referenced above, found that in many parts of the eastern DRC, between 60 and 75% of households could not reach a hospital or medical clinic within a four-hour walk.[104] As a result, many survivors remain ill or disfigured for the rest of their lives. Ms. Stirk from DFATD told the Subcommittee that sexual violence also contributes to the spread of HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases. Professor Gaëlle Breton–Le GoffAssociate Professor in the Faculty of Law at the University of Quebec in Montreal, informed the Subcommittee that 22% of women who have been raped in the DRC conflict are thought to be carrying HIV/AIDS.[105] Desire Kilolwa, from the Congo Yetu Initiative, stressed the serious impact that increased HIV/AIDS prevalence has on Congolese children, many of whom are orphaned because of the disease.[106] In addition to the tremendous physical suffering endured by survivors of sexual violence in the DRC, some witnesses told the Subcommittee about the psychological consequences of sexual violence. These include depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, deep-seated feelings of fear, rage and shame, loss of self-esteem, feelings of guilt, memory loss, nightmares and suicide.[107] The 2010 population survey referenced above found that 67.7% of women and 47.5% of men who had survived conflict-related sexual violence showed symptoms of depression, while 75.9% of women and 56% of men showed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. Access to mental health services for these individuals is virtually non-existent.[108] The Subcommittee learned that the pervasive and public nature of sexual violence in the DRC shatters family and community relationships, stigmatizing survivors and isolating them from social networks.[109] As a result, the socio-economic consequences of conflict-related sexual violence may be severe. Consequences can include rejection by husbands, families and communities, displacement, loss of educational opportunities and loss of an individual’s ability to earn a livelihood.[110] a. Effects on ChildrenIn the DRC, sexual violence has taken a particular toll on children, both directly and indirectly. The physical consequences of sexual violence are often more severe for girls than for adult women because they are not fully physically developed. For instance, girls who become pregnant after being raped are more likely than adult women in the same situation to suffer from obstructed birth, which can lead to fistulas or even death.[111] The Subcommittee was told that both girl and boy child soldiers are frequently subjected to sexual violence. After demobilization, boys suffer stigmatization and marginalization because of their status as former rebels. Ms. Kalla told the Subcommittee that demobilized girl child soldiers experience gender-specific consequences including shock, shame and low self-esteem. In a survey conducted by the ICC’s TFV, more girl than boy child soldiers reported that their communities of origin treated them poorly. The double burden of forced enlistment and sexual violence on girls means these consequences tend to be more severe, more long-lasting and more difficult to reduce.[112] The pervasive insecurity caused by widespread sexual violence against women and girls also has an indirect effect on children by undermining the critical social structures — including family, religious communities, health and education systems — upon which children rely for their healthy development.[113] Like their mothers who survive wartime rape, children born as a result of sexual violence also suffer from rejection and stigmatization. The Subcommittee was told that, in regions where many live at a subsistence level, such children frequently are not accepted into their mothers’ families, “which means that often these children are not able to go to school or even nutritionally receive the same food within a household.”[114] Overall, Ms. Kelly argued that an “integrated family-based approach” is required in sexual violence interventions in order to address the interconnected nature of problems faced by children, families and communities who have been affected by conflict-related sexual violence.[115] 3. The Subcommittee’s ObservationsThe Subcommittee is convinced that sexual violence in the context of armed conflict and crisis in the DRC is a criminal, humanitarian and human rights issue of the utmost importance. The international community, including neighbouring states, regional organizations, UN institutions and agencies, as well as donor countries and countries that contribute troops and other personnel to MONUSCO, must no longer minimize, overlook, tolerate or excuse sexual violence, forced marriage and sexual slavery. The short and long-term effects of conflict-related sexual violence discussed by witnesses demonstrate that such acts can prevent survivors — most of whom are women and girls — from benefitting from the full range of their internationally protected human rights, including the following economic, social and cultural rights:

Conflict-related sexual violence also has a negative impact on the ability of women and girls, men and boys to fully enjoy their civil and political rights. Victims who die as a result of conflict-related sexual violence suffer an arbitrary deprivation of life, contrary to the guarantees provided by international law.[117] In addition, the physical and mental harm and suffering caused by conflict-related sexual violence negates the right of victims to security of the person and, in some cases, can violate their right to freedom from torture and from cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.[118] As the Subcommittee has stressed above, acts of sexual violence, murder, violence to the person and torture may also amount to crimes under international law.[119] The evidence before the Subcommittee also clearly demonstrated the tragic effects that armed conflict has on children. The Subcommittee notes that international humanitarian law[120] attempts to mitigate the worst of these effects by requiring parties to a conflict to take all feasible measures to ensure the protection and care of children, including by protecting them from sexual violence and ensuring their continued access to education.[121] Similarly, the use of children as soldiers or militia fighters is banned unequivocally in international law and also may constitute an international crime.[122] Under international human rights law, the government of the DRC also has additional protective obligations towards children and a duty to protect and assist families.[123] In particular, it must take steps to combat discrimination against children affected by sexual violence; to protect their physical safety and human dignity; and to ensure that they have equal access to education, health care and development.[124] Finally, the Subcommittee wishes to point out that it is the responsibility of the DRC government, and any other governments in the region where perpetrators may be found, to ensure that those responsible for crimes of sexual violence are brought to justice.[125] The Subcommittee recalls that, under international law, military commanders and civilian leaders can be criminally prosecuted if they plan, encourage, overlook or turn a blind eye to crimes of sexual violence committed by their troops or fighters under their control.[126] Survivors, families and communities have a right to see their attackers held to account. The Subcommittee emphasises that the Government of the DRC’s obligation to protect the dignity and rights of its people does not cease in periods of armed conflict or emergencies resulting from violence, political events or natural disasters.[127] C. Congolese and international responses to conflict-related sexual violenceIn the following sections of the case study, the Subcommittee considers the evidence it received regarding positive steps the DRC has taken to address the problem of conflict-related sexual violence and then outlines its concerns regarding Congolese and international responses to this important issue. 1. Positive Developments in the Fight against Conflict-related Sexual Violence in the DRCa. Constitutional and Legal ReformsSeveral witnesses who appeared before the Subcommittee stressed that in recent years, the Government of the DRC has gained a better understanding of the scale and complexity of conflict-related sexual violence in its eastern regions. As a result, the government has taken some steps to counteract the problem and to improve respect for human rights in the country. The Subcommittee was pleased to learn that the Constitution of the DRC makes the government responsible for ensuring the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women and the elimination of sexual violence. The DRC government is also constitutionally required to combat all forms of violence against women in the public and private spheres.[128] In addition, the Government of the DRC has strengthened its criminal law to prevent and address sexual violence by adopting, in July 2006, two laws on sexual violence amending the Congolese Penal Code and the Code of Penal Procedure. Professor Breton-Le Goff told the Subcommittee that these reforms have introduced new criminal offences and clarified the definition of the crime of rape under Congolese law by criminalizing for the first time acts such as object rape, marital rape, forced marriage, forced pregnancy, sexual mutilation and sexual slavery. Criminal procedure reforms have also provided fairer treatment for victims of sexual offences.[129] The Subcommittee recalls that criminalizing and effectively prosecuting the full range of crimes of sexual violence is vital to ensuring the right of women and girls to live free from discrimination and to enjoy equality before the law, as well as to protecting individuals’ rights to life, security of the person, freedom from torture and other rights. The criminal law reforms discussed above provide the DRC with key tools with which to hold perpetrators of sexual violence to account. According to an official from DFATD, Marie Gervais-Vidricaire, Director General of the Stabilization and Reconstruction Task Force, one the most positive trends with respect to the fight against sexual violence in the DRC has been the government’s greater capacity and will to prosecute perpetrators of sexual violence.[130] Other witnesses echoed this point.[131] In 2004, the Government of the DRC requested assistance from the ICC to investigate and prosecute those individuals suspected of bearing the greatest responsibility for the commission of international crimes (e.g., war crimes and crimes against humanity).[132] The Subcommittee is pleased that the DRC has recognized the ICC’s ability to complement the country’s domestic efforts to bring some of the world’s worst perpetrators of sexual violence to justice. The Subcommittee notes, however, that the ICC is a court of last resort and therefore, at the national level, efforts should continue to be made to strengthen the Congolese justice system’s capacity to investigate and prosecute crimes of sexual violence.[133] The reinforcement of the Congolese justice system is particularly important in light of the fact that crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide, including sexual violence and “other massive violations of human rights,” are excluded from the amnesty extended to M23 rebels as part of the commitments made to end their mutiny in December 2013.[134] b. National PoliciesThe Subcommittee was also told that in recent years the Government of the DRC has put in place “national plans and policies to fight sexual violence.”[135] Julia Hill, then the Acting Senior Vice-President, Geographic Programs Branch, DFATD, informed the Subcommittee that the DRC has developed a National Strategy against Gender-Based Violence (Stratégie nationale de lutte contre les violences basées sur le genre) and a National Policy on Gender (Politique Nationale Genre).[136] The Subcommittee also notes that the UN peacekeeping mission in the DRC (MONUSCO) developed a “Comprehensive Strategy on Combating Sexual Violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo” which has been integrated into the National Strategy against Gender-Based Violence.[137] Mr. Tougas told the Subcommittee that the Government of the DRC and the UN have implemented several other initiatives with the goal of improving the coordination of initiatives against sexual violence. He added that among the most important of these measures is the Stabilization and Reconstruction Plan for War-Affected Areas (Le Programme de stabilisation et de reconstruction des zones sortant des conflits armées [STAREC]). It was developed by the Congolese government in 2009 in connection with the UN’s strategy to coordinate international action in the DRC[138] in order to implement UN Security Council Resolution 1925 (2010) on the DRC, which set out MONUSCO’s original mandate.[139] The Subcommittee also observes that in January 2010, the DRC unveiled its National Action Plan for the implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on women, peace and security.[140] Given the scale and the gravity of conflict-related sexual violence in the eastern DRC, the Subcommittee is pleased that the Government of the DRC has demonstrated awareness of the problem of sexual violence and of the need to take action. Nevertheless, stronger state and international action is needed. 2. The Subcommittee’s Concerns Regarding Responses to Widespread and Systematic Sexual Violence in Conflict Zones of the DRCThe Subcommittee is concerned that, while the DRC now has several policies and initiatives formally in place, sexual violence and impunity remain a day-to-day reality in the country’s conflict-affected areas. In the course of this study, witnesses identified a number of underlying human rights concerns that contribute to its continued prevalence. Significant gender inequality, weak democratic governance and institutions, failures of military command and control, the involvement of the security forces in human rights violations and a climate of impunity have had a devastating impact on human security, particularly in the eastern part of the country. The Subcommittee is also aware that local conflicts and land issues contribute to violence and instability in the DRC. However, the Subcommittee did not hear sufficient evidence on these matters to reach any conclusions. a. The Prevalence of Discriminatory Attitudes towards WomenThe Subcommittee was told that discriminatory attitudes towards women and deep-rooted gender inequality were critical underlying factors contributing to the prevalence of sexual violence used as a weapon of war in the DRC.[141] The DRC ranked 144th of 148 countries in the United Nations Development Program’s 2012 Gender Inequality Index (GII), based on 5 indicators of gender inequality: maternal mortality, adolescent fertility, parliamentary representation of women, educational attainment of women at the secondary level and above, and women’s participation in the labour force.[142] Ms. Coutu testified that in the DRC “[w]omen have no social status [...]. Without men, they are nothing. Their access to material or basic needs is completely reduced.”[143] Witnesses informed the Subcommittee that widely accepted social attitudes in the DRC also excuse or justify interpersonal violence against women and girls, including sexual violence.[144] Indeed, conflict-related sexual violence occurs within a national social context where rates of domestic violence, including sexual violence, are already high.[145] Ms. Kelly’s research provides an interesting example. She told the Subcommittee that fighters in one militia tended to distinguish between “evil rape” (e.g., rape of the very young or very old and forced incest) and “okay rape” as a way of justifying certain types of abuse. Ms. Kelly highlighted the need to reinforce the message that “all rape is rape” and to work toward changing the attitudes of fighters and government soldiers towards women.[146] The Subcommittee was disturbed to learn from witnesses that survivors of sexual violence in the DRC often are seen as a source of shame or dishonour. Survivors may find themselves rejected by spouses, family and friends and stigmatized in their communities. Some survivors have been forced to leave their families or communities and may in turn be pushed into transactional sex work to survive and to support their children. The Subcommittee was told that deeply held discriminatory beliefs have, in extreme cases, resulted in victims of sexual violence being murdered by family or community members.[147] As an illustration of the practical problems that can arise when addressing the legacy of conflict and sexual violence in such a context, witnesses pointed to gaps in the Government of the DRC’s disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) program available to women and girls. Despite the fact that about 30% of child soldiers in the DRC are female, the Congolese DDR program had failed to consider the different needs of boys and girls, leading to a situation where girls have not benefitted equally from rehabilitation assistance. In addition, disarmament, demobilization and reintegration programs in the DRC have provided inadequate support to women who are the primary providers for children at the time they demobilize. More work is needed, both by the Congolese government and by international actors and donors, to ensure that DDR programs are gender sensitive and that they address the needs of women and girls who were formerly associated with armed actors.[148] Witnesses before the Subcommittee argued convincingly that developing and effectively implementing policies that empower women are crucial components of efforts to address sexual violence in armed conflict.[149] As the Subcommittee noted above, the Government of the DRC has taken positive steps towards elaborating such policies. However, given that discriminatory practices remain deeply entrenched in Congolese society, the effective implementation of gender equality policies requires significant political will.[150] Ms. Stirk, from DFATD, informed the Subcommittee that “unfortunately, the Congolese state's capacity to enforce laws against sexual violence as well as gender inequity is limited.” The Subcommittee was told that, despite the hard work of some DRC ministries, as a whole, the government had failed to prioritize gender equality initiatives. It had also been reluctant, overall, to address the problem of sexual violence as a form of discrimination against women and as an extreme consequence of underlying gender inequality.[151] The Subcommittee observes that international human rights law requires that the DRC effectively protect women and girls from acts of discrimination, including acts of sexual violence. The DRC must also establish legal protections for women and girls on an equal basis with men and boys and take steps to ensure that men and women enjoy substantive equality.[152] In particular, as a state party to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, the DRC needs to take steps to work towards modifying and eliminating social and cultural patterns of behaviour and discriminatory stereotypes that regard women as subordinate or inferior to men. The UN Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women has observed that such stereotypes and behavioural patterns “may justify gender-based violence as a form of protection or control of women.”[153] The Subcommittee wishes to take this opportunity to emphasize that women’s rights are human rights. As such, the Subcommittee believes that the Government of the DRC urgently needs to prioritize the implementation of measures designed to combat gender-based discrimination — measures required by its own Constitution. The Subcommittee urges the Government of the DRC to live up to the international commitments that it has made and to ensure the substantive equality and equal protection of men and women, girls and boys in its country. b. A Pressing Need for Security-Sector ReformWitnesses stressed the urgent need for reform of the Congolese security forces, particularly the FARDC, so that they are able to effectively protect the DRC’s civilian population against internal and external threats. The Subcommittee notes that under international human rights and humanitarian law and related standards, security forces are expected to be disciplined, professional and accountable.[154] The Subcommittee was told that a lack of professionalism and cohesion inside the Congolese security forces, notably the FARDC, has hindered them from effectively neutralizing non-state armed groups that operate in the eastern regions of the country. Moreover, it has led to a situation where members of the Congolese army are reported to have committed serious violations of international law themselves, including crimes of sexual violence. Ms. Vaugrante said: The army is heterogeneous, composed of untrained and completely unscreened soldiers, including some former members of armed groups who have often retained their own chain of command. It commits human rights violations on a virtually daily basis. As a result, it has neither the support nor the trust of the local population it is supposed to protect.[155] Witnesses placed particular emphasis on the incomplete and problematic integration of rebel fighters into the national army. Ms. Stirk said that this integration process has led to “a lack of discipline and unity” inside the army which has, in turn, “meant that members of the Congolese armed forces are frequent violators of human rights.”[156] Ms. Vaugrante testified that Amnesty International continued “to receive information describing homicide, rape, kidnapping, forced labour, illegal detention and cruel and inhuman treatment, all attributable to [elements of] the government forces” that were previously part of non-state armed groups.[157] Following their integration into the army, certain rebel forces have continued “to pursue their own objectives”, which do “not include the protection of civilians as a priority”.[158] In Ms. Vaugrante’s view, The integration of armed groups into the army is a total failure, particularly in North and South Kivu. Those armed groups seek economic control of the region. Each wants its share of the pie, in terms of mining operations, and will do anything to get it. Consequently, this [the violence] will continue as long as the region is not safe and secure and those armed groups can do what they want, whether or not they are part of the army.[159] The Subcommittee believes that further efforts to improve the command structure of the Congolese army are vital. Reform of the FARDC is an essential step in the fight against sexual violence. Moreover, the maintenance of a democratic society requires a disciplined and professional military that is subordinate to civil authority and constrained by the rule of law. Security-sector reform, particularly the training and reform of the armed forces, should therefore be a priority for the Government of the DRC and the international community. c. A Persistent Failure to Uphold the Rule of Law and Pervasive ImpunityThe weakness of the rule of law in the eastern DRC has further complicated efforts to address the problem of conflict-related sexual violence. Professor Breton-Le Goff, for example, argued that there is virtually “a national regime of impunity for both civilians and the military hierarchy”.[160] (i) Inappropriate AmnestiesThe Subcommittee notes that the Congolese legislature adopted laws granting amnesties to former rebels for crimes committed under national law following peace talks in 2002 and 2008.[161] Ms. Mwaka argued that these amnesties, which allowed former rebel leaders to gain positions of power within the Congolese state, have undermined confidence in the DRC government’s commitment to combating impunity or seeking truth and justice for victims and survivors. She said: Today, we know that rebel forces come and rape women, but we also know that, right after the talks in Sun City [that took place in 2002],[162] forces associated with the rebels joined with the forces in power and set up a government. These are the same rebel forces who committed the crimes in the east of the DRC before coming to the table for peace talks. They have to answer for their crimes, but they now hold the power. How can we get justice from people who hold the power?[163] Victims and survivors have a right to see their attackers brought to justice.[164] In particular, the Subcommittee recalls UN Security Council Resolution 1820, which explicitly recognizes sexual violence as a tactic of war. This resolution stresses the need for “the exclusion of sexual violence crimes from amnesty provisions in the context of conflict resolution processes,” and calls upon member states to comply with their obligations to prosecute those responsible for such crimes, emphasizing “the importance of ending impunity for such acts”.[165] The past practice of effectively extending amnesties under national law to persons who are allegedly responsible for committing international crimes is gravely concerning. In light of this practice, the Subcommittee welcomes the fact that the DRC government and the M23 rebels have agreed that no amnesty should be extended to those who committed international crimes in the context of the recent M23 mutiny.[166] Nevertheless, it considers that a meaningful truth and accountability process for past crimes is also necessary to ensure that the human rights of all Congolese people are respected and protected in the future. Moreover, the alleged perpetrators of international crimes and those responsible for gross human rights violations and abuses must be prevented from working in Congolese state institutions, particularly the army, security sector and justice system. In the Subcommittee’s view, the Government of the DRC needs to implement a credible vetting process in order to establish credible transitional justice mechanisms and end impunity. (ii) Barriers to Access to JusticeIn addition to past amnesties, witnesses indicated that significant deficiencies in all parts of the Congolese criminal justice system contribute to maintaining the overall climate of impunity. These include a lack of capacity and financial and human resources throughout the justice system, nearly insurmountable barriers to access to justice for many victims, as well as a lack of independence and impartiality in the administration of justice.[167] Mr. Tougas informed the Subcommittee that “large areas of Congo have no judges or police services.”[168] Even where such services do exist, Professor Breton-Le Goff from the University of Montreal explained that [A] prosecutor may be in one city and the court in another. In a country where travel and means of communication are difficult, this raises a problem for judicial activity. In addition, neither the police nor the prosecution have the logistical means to travel to investigate on site and to question witnesses.[169] According to Mr. Tougas, this lack of resources is directly linked to the portion of the DRC’s budget dedicated to the justice system. He argued that the DRC has access to considerable resources that could be used to strengthen the justice system, but a lack of political will creates a critical impediment to addressing this resource gap.[170] The low socio-economic status of many survivors compounds institutional under-resourcing, further diminishing access to justice. Ms. Breton-Le Goff said that some victims cannot even “afford to pay for medical consultations or a doctor’s certificate, which will serve as evidence at trial.”[171] Mr. Tougas explained that for survivors of sexual violence, who must travel long distances to attend court hearings under difficult conditions, “it can cost somewhere between $700 and $800 per case to conduct a trial from start to finish, and that can take a year or a year and a half. Those are exorbitant amounts for people who live on $1 a day.”[172] In addition, the Congolese state has typically been unable or unwilling to enforce court decisions and has generally failed to pay the financial compensation to victims that it has been judicially ordered to provide.[173] Witnesses also informed the Subcommittee that perpetrators often threaten and intimidate complainants and witnesses in sexual violence cases because the DRC lacks any effective mechanism to protect them. Individuals and organizations that advocate on behalf of victims of sexual violence are also at risk.[174] Finally, the Subcommittee was told that the prisons are so poorly run that, of the few perpetrators of sexual violence who have actually been convicted, several have been able to escape.[175] The Subcommittee notes that international human rights law and standards require that remedies for human rights violations, including access to justice, be accessible in practice and properly enforced.[176] Therefore, witnesses, survivors and those who provide assistance and support to these individuals, as well as human rights defenders who advocate on their behalf, need to be protected.[177] The Subcommittee also observes that the Government of the DRC has committed itself, under the Protocol on the Rights of Women in Africa, to providing adequate budgetary and other resources for actions aimed at preventing and eradicating violence against women.[178] (iii) Lack of Judicial Independence and ImpartialityWitnesses also informed the Subcommittee that endemic corruption and a lack of judicial independence were key factors contributing to impunity in the DRC. The Subcommittee was told that this problem is particularly acute in the military courts, which take jurisdiction over most cases of conflict-related sexual violence. Interference by the chain of command in military court proceedings was identified as a particular obstacle in the fight against impunity. Mr. Tougas informed the Subcommittee that the lack of judicial independence in military courts can be highly problematic if high-ranking military or civilian officials have an interest in ensuring that certain soldiers or civilians are not successfully prosecuted.[179] In addition, under the Congolese military justice system, “a judge cannot try an individual whose rank is higher than his own.”[180] In the Congolese context, rather than reinforcing command responsibility by ensuring that commanders discharge their duty to prevent and punish unlawful behaviour by subordinates, this rule is distorted so that, in the words of one witness, “people are obviously appointed generals just before a trial, and so it is impossible to try them.”[181] One of the most direct consequences of this situation has been that “individuals who are in a situation of power and who commit sexual assault in the DRC have de facto immunity, and the justice system ultimately prosecutes the ‘small fry’.”[182] The Subcommittee notes that both international law and the Congolese constitution guarantee the independence and impartiality of the judiciary.[183] In legal proceedings, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights provides that everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal.[184] Even during situations of armed conflict, international law requires that minimum judicial guarantees be met.[185] The Subcommittee observes that judicial independence and impartiality are necessary to ensure the right to equality before the law, the right to judicial review of the legality of detention, and the fair trial rights of defendants in criminal cases such as the presumption of innocence and the right to make full answer and defence. Furthermore, effective access to competent, independent and impartial justice is necessary to ensure that those whose rights have been violated receive redress.[186] The Subcommittee considers that dysfunction in the DRC’s justice system contributes significantly to a culture of impunity for perpetrators, violates the human rights of victims and survivors of sexual violence, and undermines the rule of law. The Subcommittee hopes that the Government of the DRC, at the highest levels, will work to address these deficiencies as a matter of priority. It observes that, given Canada’s bilingual and bi-juridical legal traditions and strong military justice system, justice sector reform in the DRC is one area where Canada and Canadians could continue to contribute useful skills and expertise, in coordination with Congolese civil society organizations, other donor countries, relevant and appropriate parts of the government of the DRC, and international organizations. d. The Need to Prevent Natural Resource Exploitation from Fuelling Conflict and Sexual ViolenceThe Subcommittee heard evidence that the existence of significant natural resources in the eastern part of the DRC has been a central factor in prolonging the armed conflict. Local and foreign armed groups, as well as factions of the FARDC, have fought each other in order to gain access to and control over areas rich in natural resources. According to a representative from DFATD, armed groups benefit from the surrounding instability to “illegally control mining areas, tax miners, and traffic in minerals. These revenues are used as a source of funding to gain further control of territory.”[187] Ms. Vaugrante told the Subcommittee that many armed groups are determined to gain, maintain and extend their control over mines, airports and access routes in the eastern part of the DRC because it serves the economic interests of their leaders and others in positions of power and influence. In her view, competition over the control of income from natural resource exploitation is a key driver of the shifting alliances among the various armed groups.[188] A number of witnesses testified that, in the eastern DRC, the illegal exploitation of and trade in natural resources also contributes to the prevalence of human rights abuses, including sexual violence.[189] Ms. Joanne Lebert, formerly of Progress and Opportunities for Women’s Equality Rights (POWER)/Africa–Canada, at the Human Rights Research and Education Centre University of Ottawa, explained the link: In the Great Lakes region, protracted chaos is anchored in licit and illicit global markets. Local natural resources are highly lucrative. Easy access to these materials relies on fractured communities and the desperation of local residents who, for example, are willing to become diggers to survive — and this includes children. Revenues are, in large part, used to purchase and fuel the market and trade in small arms and light weapons. So in this context, criminality, violence, and the struggle for survival are normalized, rendering women, girls, and children particularly vulnerable.[190] Ms. Lebert argued, therefore, that the international community has to “stop seeing rape as a natural occurrence in conflict or as naturally characteristic of some societies.” Rather, she said, “rape and extreme gender-based violence emerge out of specific political and economic contexts and serve the interests of those who benefit from protracted instability.”[191] Indeed, witnesses told the Subcommittee that some armed groups and factions of the FARDC see sexual violence as a way to consolidate power and control over a territory. Ms. Vaugrante explained, “It's a monstrous and radical way for certain individuals to affirm that they are the chief and that all that belongs to them.”[192] To illustrate the connection between natural resource exploitation and sexual violence, witnesses highlighted a well-documented series of mass rapes that occurred in August 2010.[193] The Subcommittee was told that the rapes occurred after FARDC commanders re-deployed their units to ensure continuing control over natural resources, rather than fulfilling their duty to protect the civilian population from attack by militia fighters.[194] The Subcommittee notes that, since this incident in 2010, UN bodies have continued to report the use of sexual violence by militias as a tactic to gain control of mining areas.[195] The Subcommittee also noted with interest Ms. Kelly’s submission that women often migrate to artisanal mining towns to seek economic opportunities. Once there, however, many women “face horrific outcomes, and are often marginalized into undertaking sex work instead of fulfilling their right to undertake fair-paying work.” Ms. Kelley argued that artisanal mining activities should be supported in a sustainable way, with the goal of harnessing the economic potential of conflict-affected areas for the benefit of both women and men.[196] The Subcommittee believes that there is a need to target mining towns in conflict-affected areas as part of efforts to push for greater respect for women’s human rights, including the right to gain a living under just and favourable conditions.[197] The Subcommittee was told that it appears that armed groups focus principally on the exploitation of artisanal mining, as opposed to large-scale mining operations conducted by global firms.[198] As Ms. Wallström observed, however, it is important for the global mining industry to be able to trace the origins of conflict minerals in order to ensure that they are not sourced from mines controlled by the FARDC or other armed groups.[199] Conflict minerals are one of many interrelated factors that contribute to the DRC’s continued state of fragility. In this context, finding workable solutions that prioritize respect for human rights and ensure human security will not be easy. The Subcommittee stresses, however, that preventing armed actors from appropriating the natural resource wealth that should benefit the Congolese people needs to be a key part of any solution. Indeed, the failure of the Government of the DRC to govern the extraction of its vast natural resources and manage responsibly the wealth they generate has prevented the country from accessing significant revenues. This fact is particularly significant in light of the paucity of resources in the justice sector, which plays a significant role in perpetuating impunity for crimes of sexual violence. If the DRC is serious about combating sexual violence in conflict, improving its human rights record and ensuring peace and stability in the country, it cannot continue to allow its natural resources to be appropriated by those intent on terrorizing the civilian population in order to increase their personal wealth and power. [41] CIA World Factbook, Democratic Republic of the Congo, People and Society. [42] Ibid. [43] CIA World Factbook, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Economy – overview; The Economist-Intelligence Unit (EIU), Congo (Democratic Republic), “Economy – Annual indicators”. [44] United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Democratic Republic of the Congo. [45] DFATD, Response to Question Taken on Notice, 1 November 2011, providing literacy figures from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). For a complete education profile of the DRC, see: UNESCO, “UIS Statistics in Brief, Education (all levels) profile – Democratic Republic of the Congo”. [46] The International Institute for Strategic Studies, Armed Conflict Database, DRC (conflict summary). [47] At the time of Ms. Stirk’s appearance, the department was known as the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT). DFAIT was amalgamated with the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) to become the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD) effective 26 June 2013, when the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Act, S.C. 2013, c. 33, s. 174, came into force. For ease of reference, this report refers to DFATD rather than to the former departments of DFAIT and CIDA. [49] See, e.g., Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Final Report, Security Council, 15 November 2012, UN Doc. S/2012/843. [50] SDIR, Evidence, Meeting No. 3, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 25 October 2011 (Jillian Stirk); Christiane E. Philipp, “Congo, Democratic Republic of the”, Max Planck Encyclopedia of International Law, Oxford University Press, February 2013; United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), “MONUSCO Background”; International Crisis Group, Congo: Bringing Peace to North Kivu, Africa Report No. 133, 31 October 2007, Annex A. [51] United States Institute of Peace, “Peace Agreements: Democratic Republic of the Congo”. [52] UNSCR 1279 (1999), para. 5. [53] Philipp, “Congo, Democratic Republic of the”, Max Planck Encyclopedia of International Law, 2013; Emizet François Kisangani, Civil Wars in the Democratic Republic of the Congo 1960-2010, Boulder, Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2012, pp. 151-152. [54] See: IHS Jane’s, “Jane’s Sentinel Security Assessment – Central Africa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Non-state armed groups”, January 2012. [55] United Nations, “MONUSCO Background”; European External Action Service, “EU relations with Democratic Republic of the Congo”. [56] Peace Agreement Between the Government and Le Congrès National Pour la Defense du Peuple (CNDP), Goma, 23 March 2009. See: International Crisis Group, Eastern Congo: Why Stabilization Failed, Africa Briefing No. 91, 4 October 2012; International Crisis Group, Congo: Bringing Peace to North Kivu, Africa Report No. 133, 31 October 2007; “DRC: Cautious welcome for Kivu peace deal”, IRIN, 29 January 2008. [57] Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Interim Report, Security Council, 18 May 2009, UN Doc. S/2009/253, paras 18-19; Jason Stearns, North Kivu: The Background to Conflict in North Kivu Province of Eastern Congo, Rift Valley Institute Usalama Project, 2012, pp. 39-41. [58] Security Council Report, “Chronology of Events: LRA-affected areas”, 3 July 2013; Human Rights Watch, “The Christmas Massacres: LRA attacks on Civilians in Northern Congo”, 16 February 2009. [59] The arrest warrants allege responsibility for crimes against humanity

and war crimes committed in Uganda in 2003–2004. The warrants for Joseph Kony

and his alleged second-in-command, Vincent Otti, include crimes of sexual

violence. See: Warrant

of Arrest for Joseph Kony Issued on 8 July 2005 as Amended on 27 September

2005, Public Redacted Version, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/05, Pre-Trial

Chamber II, 27 September 2005; Warrant of Arrest for

Vincent Otti, Public redacted version, Case No. ICC-02/04, [60] See, e.g.: Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences et al., Third joint report of seven United Nations experts on the situation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, General Assembly, 9 March 2011, UN Doc. A/HRC/16/68; UN Joint Human Rights Office (UNJHRO), Report of the United Nations Joint Human Rights Office on Human Rights Violations Perpetrated by Armed Groups During Attacks on Villages in Ufamandu I and II, Nyamboko I and II and Kibabi Groupements, Masisi Territory, North Kivu Province, Between April and September 2, 2012, MONUSCO & Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), November 2012; UN Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Midterm Report, Security Council, 19 July 2013, UN Doc. S/2013/433; Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Interim Report, Security Council, 18 May 2009, UN Doc. S/2009/253, paras 18–19, 86–90; Kisangani, Civil Wars in the Democratic Republic of the Congo 1960-2010, Boulder, Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2012, p. 156. [61] SDIR, Evidence, Meeting No. 25, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 1 March 2012 (Patricia Malikail). [62] Ibid. The UN has documented human rights violations during the electoral period and the Government of the DRC’s response in: UNJHRO, Report by the United Nations Joint Human Rights Office on the Violations of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms Committed During the Electoral Period in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, as well as on the Actions Taken by Congolese Authorities in Response to these Violations, October 2011 – November 2013, MONUSCO & OHCHR, December 2013. [63] SDIR, Evidence, Meeting No. 25, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 1 March 2012 (Patricia Malikail). [64] UNJHRO, Report of the United Nations Joint Human Rights Office on Human Rights Violations Perpetrated by Soldiers of the Congolese Armed Forces and Combatants of the M23 in Goma and Sake, North Kivu Province, and in and around Minova, South Kivu Province from 15 November to 2 December 2012, MONUSCO & OHCHR, May 2013, pp. 9–11; UNJHRO, Report of the United Nations Joint Human Rights Office on Human Rights Violations perpetrated by Armed Groups during Attacks on villages in Ufamandu I and II, Nyamaboko I and II and Kibabi Groupements, Masisis Territory, North Kivu Province, between April and September 2012, November 2012, p. 11; Human Rights Watch, “Democratic Republic of the Congo: UPR Submission 2013,” 24 September 2013; Final Report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, UN Security Council, 15 November 2012, UN Doc. S/2012/843, paras 6–55, 147, 153–158. [65] International Crisis Group, Eastern Congo: Why Stabilization Failed, Africa Briefing No. 91, 4 October 2012. [66] Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Addendum to the Interim report of the Group of Experts on the DRC (S/2012/348) concerning violations of the arms embargo and sanctions regime by the Government of Rwanda, Security Council, 27 June 2012, UN Doc. S/2012/348/Add.1, para. 2; Final Report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Security Council, 15 November 2012, UN Doc. S/2012/843. [67] Prosecutor v. Bosco Ntaganda, Case No. ICC-01/04-02/06, Decision on the Prosecutor’s Application under Article 58, Public Redacted Version, Pre-Trial Chamber II, 13 July 2012; UN Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Midterm Report, Security Council, 19 July 2013, UN Doc. S/2013/433, paras 26-27. See paras 9–30 for a full description of the infighting in M23 that led to the surrender of Mr. Ntaganda. [68] Kenny Katombe, “Defeated M23 ends revolt in Congo, raising peace hopes”, Reuters, 5 November 2013. [69] Joint ICGLR-SADC Final Communiqué on the Kampala Dialogue, Nairobi, 12 December 2013; Declaration of the Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo at the End of the Kampala Talks, Nairobi, 12 December 2013; Declaration of Commitments by the Movement of March 23 at the Conclusion of the Kampala Dialogue, Nairobi, 12 December 2013. For Canadian and international reaction, see: DFATD, “Canada Welcomes Conclusion of Kampala Dialogue”, News Release, 14 December 2013; “Ban welcomes signing of declarations between DR Congo-M23”, UN News Centre, 13 December 2013; MONUSCO, “International Team of Special Envoys for the Great Lakes Joint Statement on the Conclusion of the Kampala Dialogue”, 13 December 2013. [70] See: EIU, Country Report – Democratic Republic of the Congo, “Summary”, 7 January 2014; EIU, “UN force begins operations against FDLR rebels”, 12 December 2013; EIU, “Fighting Intensifies in Ituri”, 2 October 2013; International Crisis Group, “DR Congo”, CrisisWatch Database, 2 January 2014; UN News Centre, “DR Congo: UN boosts force in east after gruesome massacre of civilians”, 16 December 2013. [71] SDIR, Evidence, Meeting No. 25, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 1 March 2012 (Patricia Malikail). The Rwandaphone community speaks the Kinyarwanda language. [72] SDIR, Evidence, Meeting No. 3, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 25 October 2011 (Jillian Stirk); SDIR, Evidence, Meeting No. 4, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 27 October 2011 (Desire Kilolwa, President and Founder, Congo Yetu Initiative). [73] Report

of the Panel on Remedies and Reparations for Victims of Sexual Violence in the

Democratic Republic of the Congo to the High Commissioner for Human Rights,