SECU Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

ECONOMICS OF POLICINGPART 1: INTRODUCTIONPolicing is an essential public service. It is fundamental to the well-being and vitality of our communities and to the safety of Canadians. Equally important is the need to maintain public confidence through efficient and effective policing. Our Canadian police forces have a long–standing and “well-earned reputation” for being stable, publicly supported, modern and professional.[1] Yet, all would agree that police services across the country are facing unprecedented challenges. As public expectations continue to rise and calls for service increase, police costs are spiralling to the point where the current policing model is no longer sustainable. A. Terms of Reference and Review ProcessOn 29 May 2012, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security (“the Committee”) was given a mandate to conduct a study into all aspects of the economics of policing. This is a wide-ranging issue touching upon police services, all levels of government and the broader health and criminal justice systems. The Committee sought to gather information on how to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of law enforcement in Canada by speaking with representatives of federal, provincial, territorial, municipal and Aboriginal[2] police forces. The Committee held a total of 21 public hearings in Ottawa, inviting representatives from many government and non-governmental organizations, as well as individuals, from across the country and from the United States (U.S.) and the United Kingdom (U.K.).[3] The Committee heard that identifying cost-saving measures in policing can be difficult due to a lack of evidence-based research and limited sharing of best practices amongst agencies and policing bodies. As such, it was important to the Committee to visit different communities in order to gather and prepare a synthesis of information with a view to providing recommendations on best practices. The members felt it was imperative to go beyond written reports and formal meetings; it wanted to witness first-hand concrete examples of innovative community policing, global policing reform and cost-cutting measures. With this goal in mind, the Committee undertook a series of fact-finding missions to western Canada, the U.S. and the U.K. Committee members wanted to meet with police officers “on the beat” in order to get a taste of their daily administrative burdens and challenges. The members also wanted to gain a better appreciation of the individuals with whom police officers interact on a daily basis and who often fuel the calls for service. During its travels, the Committee had the opportunity to hear from numerous community organizations and policing partners in settings that allowed the members to appreciate the passion and devotion of the individuals they met. The Committee found their evidence compelling and invaluable to its study. The Committee would like to thank all of the witnesses, government officials and interlocutors for their time and for sharing their experiences. PART 2: THE CURRENT CANADIAN POLICING FRAMEWORKThe Canadian policing landscape is characterized by the vastness of our country, its cultural diversity and its jurisdictional framework.[4] This reality is at the core of many of the challenges inherent to the delivery of efficient and effective police services. A. Distribution of PowersIn Canada, the constitutional distribution of legislative powers grants the federal government the responsibility of enacting criminal laws.[5] The Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness (the Minister) is mandated to exercise leadership for public safety matters in Canada. Pursuant to the Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Act, the Minister provides direction to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Canada’s national police service.[6] As a result of the distribution of powers, provincial governments have the primary responsibility for policing in Canada, based on the “administration of justice” authority in section 92(14) of the Constitution Act, 1867.[7] From an operational perspective, policing responsibilities have, to a considerable degree, been delegated to the municipalities, which provide the majority of policing services in Canada.[8] By way of illustration, the Police Services Act of Ontario states that every municipality “shall provide adequate and effective police services in accordance with its needs.”[9] If the municipality is unable to provide police services, it is stated that the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) shall provide its services, to be paid in return by the municipality.[10] B. Municipal, Provincial and Contract PolicingMunicipalities pay for 60% of policing in Canada and municipal stand-alone police forces serve 77% of all Canadians. Municipal governments pay the salaries of two out of three police officers across the country and policing and public safety costs currently make up 20% to 50% of municipal budgets, depending on the community.[11] Other communities are served directly by their provincial police service (in Newfoundland and Labrador, Ontario and Quebec) or through cost-shared contract policing arrangements whereby a municipality, a province or a territory enters into a contract policing agreement with the federal government, or whereby a municipality enters into a policing services agreement with another municipality or provincial police force. Berry Vrbanovic, past president of the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, informed the Committee that approximately 15% of Canadians live in communities served by RCMP contract police officers.[12] The RCMP provides contract policing to the provinces and territories on a cost-shared basis which is generally as follows: for provincial policing, there is a 70% provincial/30% federal cost‑share; for municipalities in excess of 15,000 inhabitants, there is a 90% municipal/10% federal split; for municipalities of less than 15,000, it is generally a 70% municipal/30% federal split; and municipalities not policed by the RCMP prior to 1991 must pay 100% of contract policing costs.[13] C. RCMP Federal and National PolicingIn addition to contract policing, the RCMP provides specialized support services to law enforcement and criminal justice agencies, as well as federal policing services across the country. The specialized support services include the Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC); the Canadian Police College; the Criminal Intelligence Service Canada; Forensic Science and Identification Services; the Canadian Firearms Program and the Canadian Police Centre for Missing and Exploited Children.[14] The mandate of the RCMP’s Federal Policing Services is to: investigate criminal activity linked to national security, organized crime and economic integrity; develop and share criminal intelligence; enforce federal statutes; conduct international capacity building, liaison and peacekeeping and ensure the safety of state officials, dignitaries, foreign missions, and Canadian aircraft, as well as at major events.[15] D. Aboriginal PolicingThe delivery of policing services to Aboriginal communities is administered through legacy programs[16] or negotiated agreements under the First Nations Policing Program (FNPP), by RCMP contract police, provincial police forces (in Ontario and Quebec) or self-administered Aboriginal police forces.[17] The FNPP was created in 1991 in order to provide additional policing services to those the provinces already provide through their policing programs and in a manner that is consistent with provincial police legislation.[18] It is also intended to facilitate the transition to self-administered police services. Financial responsibilities for the FNPP are shared by the federal, provincial and territorial governments with the federal government contributing 52% of the costs, and the provinces or the territories contributing 48% of the costs. It currently provides funding for policing services in approximately 400 First Nations and Inuit communities in Canada.[19] According to the 2009–2010 Evaluation of the First Nations Policing Program, there are four types of agreements managed under the FNPP:

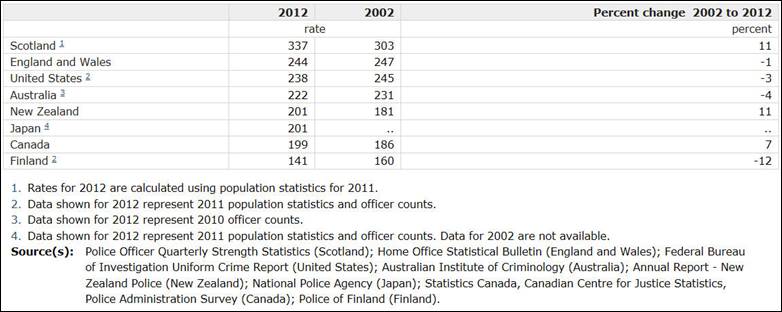

Some agreements negotiated among Aboriginal communities and provincial/territorial governments and the federal government provide for the funding of police services for individual communities. Others provide for multi-community police services, as is the case of the Nishnawbe-Aski Police Service (NAPS), which serves 34 communities in northern and northwestern Ontario and is the largest self-administered Aboriginal police service in Canada.[22] Self-administered Aboriginal police forces are the police services of jurisdiction within the communities they serve. Enhancements are provided by other policing services upon request when significant or specialized resources such as tactical response or identification services are required.[23] The RCMP plays an important role in the delivery of Aboriginal policing services as the contract police for provinces and territories and in communities policed under the FNPP. The RCMP has Aboriginal policing service units in each of its divisions across Canada. They are responsible for the oversight, coordination, and delivery of services under the RCMP’s Aboriginal Police Program and the FNPP in Aboriginal communities. Division commanding officers retain Aboriginal advisers to provide a cultural perspective on matters pertaining to the delivery of Aboriginal policing services. These advisers report to the Commissioner of the RCMP, in the form of a committee that provides guidance and recommendations on issues of national concern.[24] PART 3: COST DRIVERS AND CHALLENGESA. Police Officer Strength, Police Expenditures and Cost Drivers in PolicingDiscussions about the evolution and sustainability of policing are not new. In fact, the Committee learned that in 2008, key stakeholders such as the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police (CACP), the Canadian Police Association (CPA), the Canadian Association of Police Boards (CAPB), and the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) began discussing a policing framework that was said to better reflect the reality of Canadian policing. In 2010, the CAPB took the lead in forming a national coalition with other stakeholders on sustainable policing.[25] Public Safety Canada was considered to be an ally in the work of the coalition. Soon thereafter, the economics of policing was discussed at a Federal/Provincial/Territorial (FPT) meeting and was the subject matter of a national policing summit in January 2013. In terms of officer-population ratios, Canada is presently at the lower end of the spectrum when compared to other western countries.[26] This is reflective of the significant efforts already made by the policing community to adjust to changes in policing.[27] Canada currently employs 199 police officers per 100,000 population, well below countries such as the U.S. at 238, England and Wales at 244, Australia at 222, and Scotland at 337 officers per 100,000 population.[28] In fact, the police officer numbers for England and Wales and for Scotland already reflect the massive cutbacks to officer strength which their police services have undergone.[29] Table 1 – Police Officers per 100,000 Population, Selected Countries

Source: Statistics Canada, Police Resources in Canada, 2012 As illustrated in Figure 1 below,[30] the Committee has heard that the police-reported crime rate has continued to decline since the early 1990s, both in Canada and in other industrialized democracies. Reasons for this decline include improvements in policing intervention methods, as well as changing demographics.[31] Figure 1 also demonstrates that while the number of police officers per capita has remained relatively stable since the early 1970s, the crime rate rose to its highest level in the early 1990s and has been gradually declining ever since. In other words, one cannot conclude that there is any causal relationship between the number of police officers and the crime rate. Figure 1 – Crime Rate and Police Strength per 100,000 Population, Canada, 1962–2012

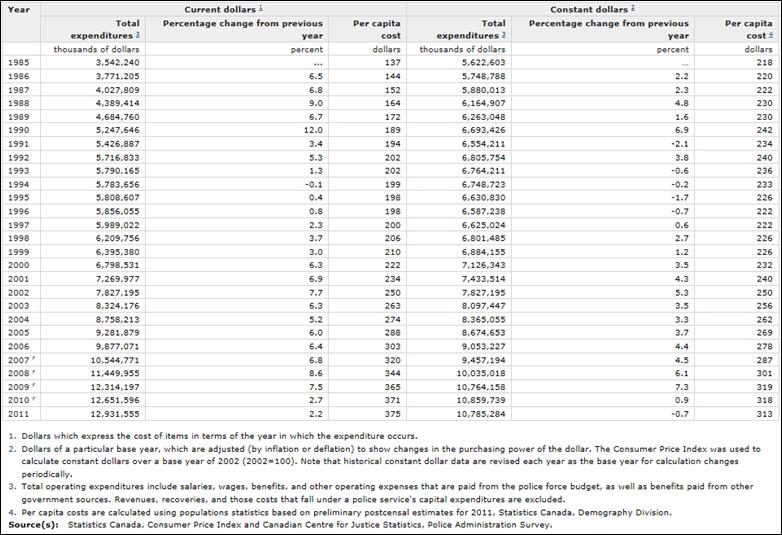

Source: Statistics Canada, Police Resources in Canada, 2012 As illustrated by Table 2 below, police service operating expenditures in Canada totalled $12.9 billion in 2011, increasing steadily from $3.5 billion in 1985. While in 2011, constant dollar spending declined slightly (-0.7%) from the previous year, this marked the first decrease in this figure since 1996.[32] It is expected that by 2015, we will be spending $17 billion due to current collective agreements and locked-in contracts.[33] Table 2 – Current and Constant Dollar Expenditures on Policing, Canada, 1985 to 2011

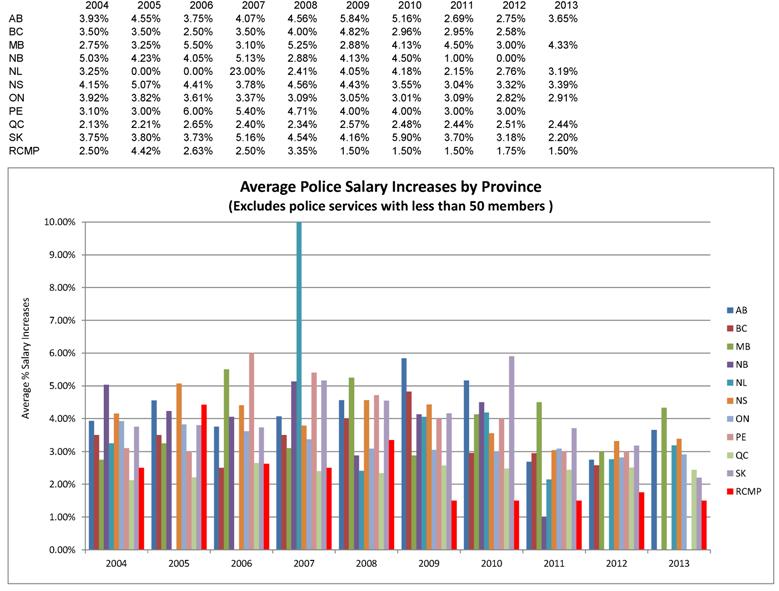

Source: Statistics Canada, Police Resources in Canada, 2012 The evidence heard clearly demonstrates that while police strength in Canada is significantly lower than in other western countries and police-reported crime rates are declining, police expenditures continue to increase and Canadian police forces remain very busy. Although it is important to not oversimplify the complexity of the issues at hand, the Committee believes, after hearing from a full array of stakeholders, that one of the keys to reconciling this seemingly contradictory information lies in looking beyond strict economic analyses towards a broader consideration of the main cost drivers of police work today. Indeed, the Committee’s approach has revealed the profound extent to which societal and legal changes have affected the delivery of police services. Through its witnesses, the Committee has identified the following primary drivers of policing costs today, namely: an increase in call volume due to social disorder and mental health issues, the changing nature of crime, increasing police sector compensation and the demands placed by the criminal justice system on the police. 1. Police Sector CompensationThe increasing costs of policing in Canada have been driven in large part by an overall trend of significant growth in police officer salaries, which have increased by 40% over the last decade, outpacing the Canadian average of 11%.[34] Indeed, per-unit labour costs for both police officers and civilian police employees are higher than ever. Since 1999, police compensation has significantly outpaced inflation, and the cost of pensions, benefits and overtime have been major contributors to those costs.[35] Figure 2 – Police Salary Trends by Province: Average Police Salary Increases by Province

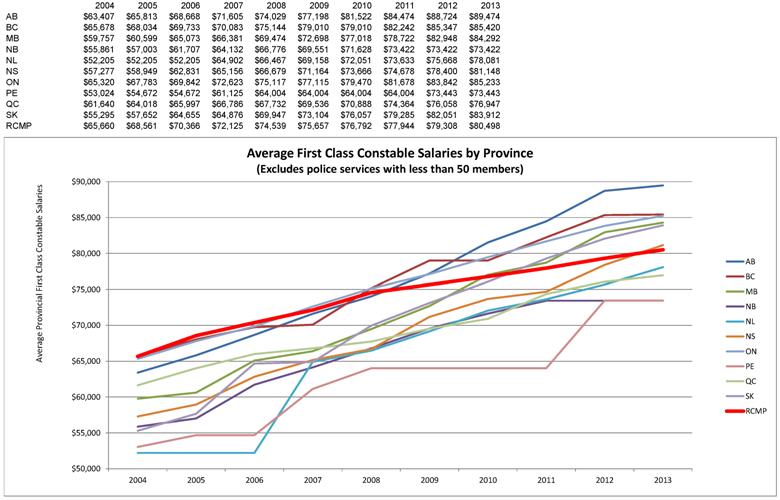

Source: Royal Canadian Mounted Police Factors such as the “ratcheting up of salaries through collective bargaining with first responders”,[36] a lack of understanding of the realities of the economics of policing by employees[37] and the arbitration process in some jurisdictions[38] have been identified by witnesses as underlying causes of the high rate of growth in police officer salaries. Figure 3 – Policy Salary Trends by Province: Average First Class Constable Salaries by Province

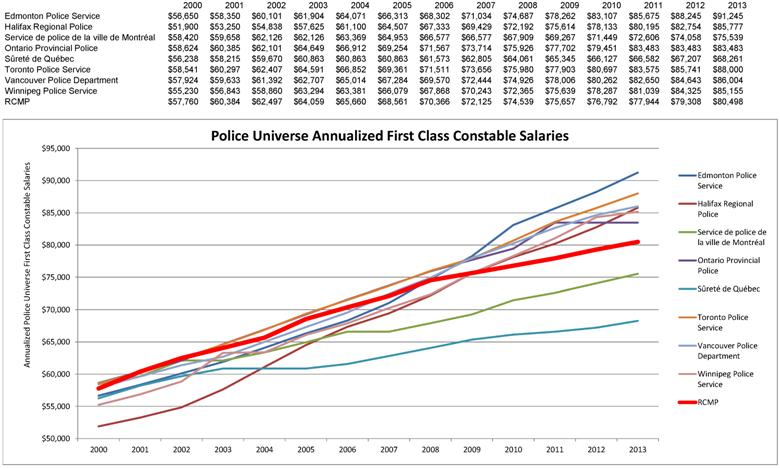

Source: Royal Canadian Mounted Police The Committee heard that because of the cost of police compensation, police services have limited room in their budgets for cost savings. Human resources expenses are typically in the 80% to 90% range of police service budgets, leaving only 10% to 20% for spending on other expenses related to police service delivery, including mandatory costs for the procurement and maintenance of infrastructure, technology, equipment, vehicles, training and other costs associated with managing a workforce.[39] According to Geoff Gruson, Executive Director of the Police Sector Council: [I]t’s not very useful to place the burden of solutions to the economics of policing on individual command executives or their individual police services. They have very few discretionary options when it comes to their own budgets. They have very little control over 95% to 96% of the costs and can only really exercise discretion when it comes to triaging crimes or their responses to social issues or social misconduct, which for some services make up almost 75% of their calls for service.[40] As noted by many witnesses, however, the nature of police work is complex and difficult. Police officers must have the training, judgment, and interpersonal communication skills needed to deal with individuals in distress and recognize that situations can range from those involving individuals simply needing some assistance to those presenting a potential for violence.[41] In order to attract and retain such individuals, police officers must be paid sufficient salaries. As noted by Chief Rod Knecht of the Edmonton Police Service, “policing is very expensive, and like most commodities, you get what you pay for.”[42] Figure 4 – Police Universe Annualized First Class Constable Salaries

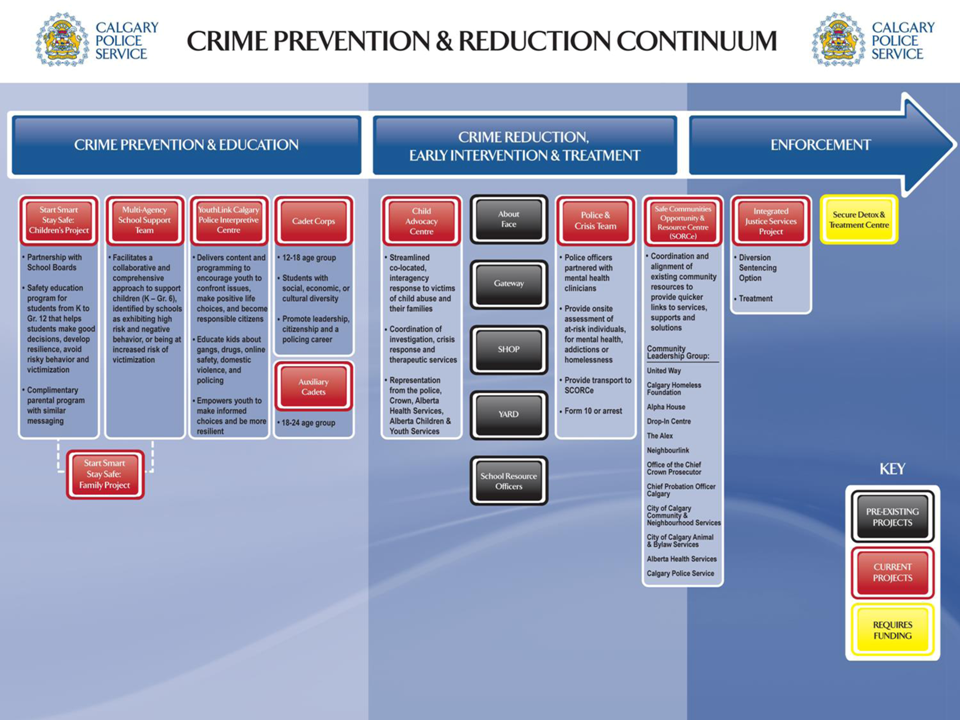

Source: Royal Canadian Mounted Police In this respect, the clear message from witnesses appearing before the Committee was that increased salary costs can only be managed fiscally to a certain point, and that fundamental changes to the way policing is delivered must be considered in order to improve policing in the future.[43] 2. The Changing Nature of CrimeTechnological advancements are having a profound impact on policing, leading to the emergence of new types of crime and law enforcement priorities. Crime has become more complex, technical and mobile.[44] With respect to its complexity, Mike Cabana, RCMP Deputy Commissioner, Federal Policing, explained that the growth of data volume in any given investigation is staggering. He noted that investigations today can involve multiple telephone numbers and e-mail accounts. One recent investigation included 350,000 telephone conversations and nearly one million text messages. Inevitably, the time devoted to analyze and compile such information is considerable.[45] “Technology and globalization, which have empowered so many of us, have also empowered criminals.”[46]Financial and commercial crime, cyber-crime, the globalization of organized crime, and the heightened focus on national security and terrorism threats have also expanded the focus of police work.[47] As such, many criminal investigations are no longer confined to the territorial jurisdiction of specific police forces, provinces or countries. In order to keep up with the methods used to commit offences, the police continually need to acquire different and newer technologies.[48] In the Committee’s view, this new reality has caused significant enhanced demand on police resources. Ten years ago it was the police who had the most up-to-date technologies at their disposal; today it is the organized criminal element who have the resources and access to cutting-edge technology without legal, budgetary, or regulatory restriction, often leaving police in the position of playing catch-up or simply being neutralized.[49] 3. Increase in Call Volume: Social Disorder and Mental Health IssuesPolice chiefs from the east coast to the west coast of Canada noted the extent to which mental health and social disorder issues permeate modern police work. Law enforcement agencies have become the social and mental health services of first resort. The Committee heard that 70% to 80% of the calls police now receive are not related to crime.[50]

In his evidence, Chief Hanson illustrated how instances of social disorder can fuel calls for service. He explained that a loud, aggressive person in the community can cause residents to feel unsafe and call police. Although this person is not committing a criminal act, police services are still required to respond. The same individual can generate numerous calls for service. Calgary Police Service officers recalled the case of a man named “Martin”. This individual generated so many calls of this nature to first responders that he became known to them as the “Million Dollar Man” because responding to his calls for service cost in the area of one million dollars in a single year. The ability of police services to respond to social disorder and mental health issues varies across Canada. Factors such as demographics, money invested in the health system and the availability of mental health support networks in each jurisdiction come into play. As a result of such differences, policing bodies have had to adapt their service delivery models according to the availability of local community resources.[54] The Committee is concerned that the increase in calls has serious consequences on the availability of police resources and that the time spent dealing with such incidents is time away from core policing functions. Chief Constable Bob Rich of the Abbotsford Police Department described how, frequently, almost all of the police officers on the night shift are working on mental health act apprehensions and that police officers can spend hours waiting in emergency wards with persons they have apprehended until those persons are admitted to the institution by a doctor.[55] The financial costs and resources invested as a result of the police becoming more and more engaged in social issues relating to mental health, addictions and homelessness are significant. The magnitude of the situation was described by Chief Rod Knecht of the Edmonton Police Service in the following terms: Last year alone, Edmonton police dealt with 35,000 calls relating to mental health, addictions, and the homeless. Each call took an average of 104 minutes. If you do the math, that’s seven and a half years. Most often we are dealing with the same people over and over. We have documented over 150 contacts with a single individual during the course of the year. Our colleagues in hospital emergency wards, ambulance, and shelters are dealing with these same people, in some cases more often than us.[56] Although police services strive to deal with mental health issues as best they can through enhanced training and community partnering where available, police officers are not mental health care professionals. Professor Curt Taylor Griffiths described this broadening of police duties beyond core functions as a “massive downloading” of responsibilities to the police caused by cutbacks to other programs: Whenever a provincial government cuts back on social workers, mental health workers, probation officers, and other types of service delivery resources, at the end of the day, it’s the police officers on the street who have to deal with that. I think that if we look across the jurisdictions in Canada, we’ve seen police officers being left with an increasing number of tasks that, again, are expanding their role and expanding their activities merely because they’re the only agency available 24/7/365. At the end of the day, if there have been cutbacks in programs, oftentimes there’s an increased demand load on the police.[57] The Committee firmly believes that failure to address what are obvious health care problems can and will lead to reciprocal costs to policing. It is the Committee’s opinion that front-line police officers are not best equipped to deal with mental health issues. Consequently: RECOMMENDATION 1 The Committee recommends that governments constitutionally responsible for health care work in collaboration with local police forces through the health care system to achieve better practices when dealing with persons having mental health problems and illnesses, outside of the police being the first and only line of response. 4. Demands Placed by the Criminal Justice System on Police ResourcesMany of the police officers who appeared before the Committee emphasized their frustration with respect to the demands placed upon them by the criminal justice system. Despite having been the subject of numerous reports and reviews,[58] certain inefficiencies continue to exist and are said to be among the prime drivers of policing costs.[59] More specifically, witnesses told the Committee that officers are too often found waiting to testify in a courtroom. In fact, Chief John Paul Levesque informed the members of a recent study conducted by the Thunder Bay Police Service which showed that 82% of the officers who attend court never testify.[60] Nonetheless, officers who are required to attend court to provide their evidence are entitled to remuneration regardless of whether or not they are actually called to the witness stand. As such, the police service in question is left to cover the cost of the officer’s appearance in court. The Committee was told that officer remuneration in such cases varies pursuant to the collective agreement and the day on which the officer is scheduled to appear: It is different between police services and amongst collective agreements. For example, in the RCMP, if you go to court it’s a four-hour callback, regardless of whether you have to testify or not. For other police services, it is eight hours. It can be time and a half; in some cases it’s double time. It depends on whether it’s right after a shift as opposed to a day off. It is different amongst jurisdictions and it depends on where it fits into your schedule. In most cases, that’s all part of a collective agreement. With the RCMP not having a union, it is a bit different.[61] Geoffrey Cowper, Q.C., former chair of the British Columbia Justice Reform Initiative, told the Committee in no uncertain terms that changes to the way the justice system does business can and would have an effect on the time police spend at court. His testimony stated: If you wander around the provincial courthouses, at least in British Columbia, and you were from Mars—you weren't a Canadian—and you were wondering who lives in courthouses, the answer would be uniformed police officers, wandering around the hallway looking lost, or at least looking impatient, or sometimes just looking patient. So it's a real problem. I actually think there are various technology fixes that need to happen and this is a classic example where having six or eight police officers in the hallway might help a prosecutor, because it enables a prosecutor to say to the accused and his or her counsel, “Look, I'm ready to go; I have all of my witnesses here”, and that might result in a guilty plea that might not otherwise have happened. In my view, you can replace that system—which is frankly the practical need for those witnesses for the most part—with a call feature that shows that a police officer doesn't have to come except at a scheduled time, and the rest of the system should be able to accommodate that. I think there are a number of ways that could make that efficient and that don't require police officers to wait around.[62] Despite the use of automation and software programs by various police forces in order to help with the management of court appearances by officers, it is clear from the evidence that such programs are unable to predict or address another issue, that of last-minute resolutions between Crown attorneys and defence counsel. In addition to idle court time and repetitive court appearances, witnesses brought to the forefront the need to streamline administrative processes so that officers are not continuously tied up with paperwork. They pointed out that by spending more time behind a desk or waiting to testify in a courtroom, police officers are not out on the street and in the community where they are expected to be. Furthermore, increased legal obligations placed upon the police at the early stages of the criminal process with respect to the conduct of investigations, the issuance of search warrants and the duty to disclose were all noted as being burdensome following specific judicial decisions. Tom Stamatakis, President of the CPA, noted that “well-meaning judicial decisions” have led to increased workloads and processing times for the laying of what are considered to be basic criminal charges.[63] For instance, police officers noted additional administrative burdens with respect to the processing of impaired driving charges. The Committee was told that in 1980, the processing of an impaired driving charge could take one to two hours but that today, it can take up to eight or nine hours per officer.[64] One recent study conducted by the University of the Fraser Valley in B.C. showed that the work of police officers has changed significantly over the last 10 years, post charter and subsequent to any legislative and regulatory changes in the 1980s and 1990s, with breaking and entering at 58% more processing time, driving under the influence at 250% more processing time, and a relatively simple domestic assault at 950% more processing time.[65] Witnesses made a number of suggestions with respect to finding efficiencies within the broader criminal justice system. For example, Dale McFee, then past president of the CACP, emphasized the need to make better use of technology like electronic file transfers to meet increased disclosure obligations. He also advised that new strategies were required in order to address the bottlenecks created by repeat offenders, chronic administrative breach charges and incidents involving persons having mental health and addiction issues.[66] Many police officers have called for legislation that would better enable police to have lawful access to telecommunications data, including subscriber information, pointing out that their inability to access subscriber information held by Internet service providers in real time is having a profound effect on their investigations. When we were all in horse and buggies and didn’t have superhighways, when we built those highways we built a Highway Traffic Act that supported the laws. Now we have the information highway. We don’t have a legislative framework for the massive amounts of traffic and the speed and volume around which people use that highway. We need that legislation.[67] Cost efficiencies could undoubtedly be found through collaboration and the sharing of information concerning justice reform initiatives which give due consideration and respect to policing priorities.[68] For example, the Province of British Columbia is being recognized for its recent justice reform initiatives. Mr. Cowper explained how BC is breaking down existing silos and allowing efficiencies to be realized. His recent report recommends that regular justice summits be held to include outside agencies with a view to increasing collaboration for reform.[69] Mr. Cowper noted that a system-wide approach is needed to address the delays which occur at different points within the judicial process: I think one of the reasons why I call for a system wide-approach is because you need to realize that delay in one part of the system is going to produce delays in other parts of the system, and that improvements in one part of the system can be frustrated by responses in other parts of the system.[70] He added that the setting of benchmarks would encourage and facilitate the early resolution of cases. With respect to wait times, Mr. Cowper noted that technology could help ensure the better scheduling of police officers required to testify. Mark Potter, Director General, Policing Policy Directorate, Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness emphasized the importance of ensuring that front-line police officers are included in efforts to find efficiencies.[71] That being said, the Committee also heard that solutions cannot be found by the police alone and that they must be the result of a collective effort across government lines and amongst key stakeholders.[72] As such: RECOMMENDATION 2 The Committee recommends that the House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights consider performing a study into the economics of the judicial system, cost drivers, excessive administrative burden, and its effects on the costs of policing in Canada. B. Cost Drivers and Challenges Unique to Small, Rural and Northern Communities, including Aboriginal PolicingCanada’s unique geography and its demographic composition directly impact police service delivery costs. Witnesses noted that discussions around policing are often southern-centric, with very little attention paid to the challenges and realities of policing in rural, remote and northern areas, including Aboriginal communities.[73] 1. The Impact of IsolationThe average cost for policing in Canada is approximately $370 per person – $300 in the provinces, and $1,000 in the territories.[74] The average cost of an RCMP member in the North is approximately $220,000 compared to $121,000 in southern Canada.[75] In addition to their regular pay, RCMP members receive allowances for their work in isolated areas. Moreover, infrastructure costs in certain remote communities were described as being “phenomenal” and “astronomical”.[76] For example, recent expenditures for government accommodation in Rankin Inlet for a modular home were quoted at $600,000 and just under $1 million for a duplex recently built in Cross Lake, Manitoba.[77] As the average RCMP detachment is 30 years old, infrastructure replacement is also an issue and investments are required.[78] The cost of transporting goods is significant as they need to be flown or barged into police detachments. Some isolated communities lack detention facilities, so prisoners must be transported to nearby detachments. In addition, equipment and fuel costs have increased due in part to the shorter winter ice road season. The movement of RCMP members from the North to the South for training purposes and annual recertification also create financial and human resource pressures.[79] 2. Levels of Police Service Delivery, Working Conditions and Adequacy of FundingA. RCMP Contract PolicingThe saying that the police have become “all things to all people” takes on a particularly acute meaning with regard to rural and remote communities due to the lack of available social services. The socio-economic conditions of these areas directly impact policing costs. For instance, RCMP members are often the only government representatives on the ground and are asked to take on the role of social worker, mental health professional, substance abuse counsellor, and a host of other roles beyond traditional law enforcement.[80] As explained by Professor Griffiths, budget cutbacks in any of these regions would have an exponential impact.[81] Levels of police service delivery and working conditions will also vary, as not every community is equipped with a police detachment. In fact, policing is often provided on a fly-in basis, as required. Where levels of violence and other problems are elevated, the RCMP operates by way of regular rotational fly-ins, flying in two members and taking the other two members away.[82] Some communities have no amenities other than the RCMP detachment and a nursing station. RCMP members posted in the North can be on call 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year to respond to emergencies. It goes without saying that this pace can only be sustained for a limited period of time until police officers want to work elsewhere. In fact, RCMP members are not expected to work in isolated northern communities for more than two or three years.[83] Some regions, like those in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, have fewer detachments and so police officers are required to provide service to greater geographic areas. Consequently, longer response times are a daily reality for people living in rural Canada.[84] Despite quite a bit of interest by younger members in northern policing, it is a challenge to attract senior members with investigative skills and experience to act as mentors. In an effort to address retention issues in rural, remote and northern areas, the Manitoba RCMP “D” Division has implemented a rotation policy called “Toques before Ties.” Members are required to spend two or three years in a posting in the North before they can move south for a detective position.[85] The suitability of RCMP candidates for isolated, remote postings is determined through medical and psychological assessments.[86] The Committee notes the importance of community involvement in the northern policing recruitment process.[87] The Yukon government has been credited for being at the leading edge of police recruitment practices. As a result of the Sharing Common Ground Review of Yukon’s Police Force, the territory now requests that RCMP candidates seeking to work in the Yukon meet certain criteria, including that they want to be involved in the community, they want to live in the North and they want to learn about Aboriginal culture.[88] B. Self-administered Aboriginal Police ServicesSelf-administered Aboriginal police services face similar challenges to those of RCMP contract police in rural, remote and northern areas. Demanding working conditions and rising police salaries make it difficult to recruit and retain officers[89] when better-paying positions are available elsewhere.[90] Chief Robert Herman of the NAPS advised that recruiting difficulties have, in turn, resulted in significant overtime costs and that it is very difficult to recruit Aboriginal officers.[91] Moreover, the Committee is concerned with specific challenges faced by self-administered Aboriginal police services. The extent of the situation was illustrated by then OPP commissioner Chris Lewis who noted that the “current funding model for First Nations’ policing in Canada is not resulting in the same level of policing in many First Nation communities that is enjoyed in non-First Nation communities.”[92] It comes down to funding. In the current funding model – and this isn’t a criticism of either the federal or the provincial government – there’s the 52% that the feds give, the 48% that the province gives, and when you add those together it cannot sustain adequate policing in those communities. A 52:48 ratio is fine, but the monetary values have to increase to create infrastructure and keep people in communities who don’t want to stay there. They’ll quit and join some other police department just to get out of that community because the conditions are unbearable in some places.[93] He went on to describe a particularly worrisome situation in the First Nation communities of Ontario: Compared to the vast majority of provincial and municipal police services in Ontario, most First Nation communities are woefully under-resourced, and as a result, have inadequately trained and equipped officers. There aren’t enough officers or support staff, and the infrastructure is often poor or non-existent.[94] This is very disconcerting, given that Aboriginal communities face particular public safety challenges, including high crime rates, poor socio-economic conditions and a growing youth population.[95] For instance, the Committee heard that Aboriginal communities located near urban centres are vulnerable to gang-related and illegal drug activities due to the degree of mobility between the two locations.[96] The Committee believes that this situation underscores the need for effective and sustainable police services in Aboriginal communities across Canada. The Committee was told that NAPS officers can work alone for extended periods of time and that their backup is often a member of the band council. Other times, the NAPS officer who is working alone and needs backup has to dial in using a keypad on his radio to contact the OPP communications centre in either Thunder Bay or North Bay. The range for their portable radios is only about one kilometre and so it is normal in some communities to have two officers on portable radios who cannot communicate beyond the one kilometre range. The Committee was told that this would not meet any federal or provincial health and safety standards. NAPS officers also respond to gun calls on a continual basis. In fact, the crime severity index in the nine First Nations communities in Ontario policed by NAPS is five times the provincial average. The top five communities in Ontario on the Crime Severity Index are all First Nations communities policed by NAPS officers. Chief Herman noted that the incidence of post‑traumatic stress disorder for NAPS police officers is much higher than those of officers in other police services because of their difficult working conditions.[97] Chief Herman went on to explain that the issue of which labour legislation should be applied in the context of self-administered Aboriginal policing remains unresolved.[98] This situation is in stark contrast with policing services delivered by the RCMP to Aboriginal communities. Over the past 10 to 12 years, the Canada Labour Code and RCMP requirements for officer safety have driven the RCMP to adopt a three-person detachment model versus a two-person detachment, which allows for always having two people on the ground for backup. A benefit of this new model is that in some instances, police officers may not be very busy with criminal investigation caseloads, allowing them time to get involved in the community that they serve.[99] Then past president of the CACP, Dale McFee, speaking on behalf of the Association, advised the Committee that he supports the view that First Nations police “should be using the same rules, have the same pay rates, and have the same expectations as other police services across the country.”[100] He advised that First Nations deliver quality police services at the level set out for them in their mandate. Indeed, for example, the NAPS community-based policing program has reduced violent crime by 30% in the communities it serves and its clearance rates are higher than those of most police services throughout Canada.[101] The cost per officer under the FNPP in Ontario is around $130,000 to $140,000. In Quebec First Nations communities, from 2004 to 2011, violent crime decreased by 19%, with homicides decreasing by 36%, general assault by 20% and sexual assault by 23%.[102] The Committee heard that although there is some movement toward more communities taking ownership of their public safety needs, this was described by Chief Doug Palson, Vice-President, First Nations Chiefs of Police Association (FNCPA) as a slow process due to the socio-economic challenges faced by First Nations communities.[103] Chief Palson explained that because some First Nations communities are relatively small, a model of policing delivered by, for instance, the RCMP or the OPP, does not fit.[104] These communities want the presence, the connection and the preventative programing that self-administered police services can provide:[105] [W]ith the self-administered services you’re connected with the community. We do our best to try to have as large a complement of members who are First Nations or of Aboriginal descent as possible, which helps. We work closely with the community. That’s the biggest piece. In some cases it’s something as simple as a language issue. Some of our communities are still very traditional. The one in particular I’m thinking of is an Ojibway community where a lot of the people, even some of the younger people, still speak that language.[106] Professor Griffiths observed that with respect to self-administered Aboriginal police services, continued support is needed: A lot of it is a reflection of larger issues that may be going on on that First Nations reserve, in terms of leadership issues, capacity. Over the last couple of decades in particular, I know the RCMP and the two provincial police forces have really worked to help build that capacity and to assist autonomous First Nations police services. I think it’s a matter of continuing to provide them with support, not only fiscal support but support in terms of leadership development, succession of leadership, and ensuring that they aren’t isolated. Sometimes they tend to become isolated, not only because of their geographic isolation but also because they don’t tend to be part of the discussion […].[107] The Committee believes that the federal government should work in collaboration with Aboriginal police services when discussing the appropriate needs and responses to public safety challenges in Aboriginal communities. RECOMMENDATION 3 As First Nations policing that is culturally appropriate has been proven to have a higher success rate for public safety, the Committee recommends that the Government of Canada continue to work with First Nations communities, to further develop models which provide culturally appropriate policing and public safety programming. 3. First Nations Policing Program: Future ConsiderationsWitnesses noted that the FNPP, which is administered through Public Safety Canada, is interlaced with challenges. Although the FNPP was created in order to facilitate and support the transition to self-administered Aboriginal police services and provide additional funding in an effort to ensure comparable levels of policing, the Committee heard that this objective is not always achieved.[108] According to the FNCPA, the limited funding within the FNPP can prevent communities from having self-administered policing services. Furthermore, as standards for infrastructure, training, general operations and civilian governance are imposed by governments, there are often no funding or educational resources to allow for implementation and to ensure compliance. According to Chief Palson, Vice-President of the FNCPA funding levels are inadequate when compared with other policing services’ budgets, particularly in light of the geographic and socio-economic conditions of many First Nations communities.[109] Chief Lloyd Phillips, President of the Assembly of First Nations of Quebec and Labrador and Representative, Chief of the Mohawk Council of Kahnawake, noted that the five-year renewal of funding for the FNPP announced in 2013 is allowing “for some stability in medium term planning for First Nations which has been a longstanding concern.”[110] Chief Palson advised the Committee that, in his opinion, consultation among governments and First Nation communities on the required levels of service does not take place in a meaningful way before policing agreements are signed, despite the fact that the agreements call for this type of consultation. He advised that communities tend to be somewhat disenchanted with the process and feel that they are not respected.[111] Effective policing on First Nation territories and effective partnerships were identified as the two most pressing FNCPA priorities. While the federal and provincial governments share in the funding of Aboriginal policing, a concern was identified that adequacy of funding issues are not being dealt with due to “finger-pointing” between the federal and provincial governments on the issue of the responsibility for Aboriginal policing.[112] Chief Palson advised that the FNCPA is seeking “recognition of the constitutional relationship that sets out the responsibilities of both the federal and provincial governments toward First Nations.”[113] Chief Phillips further explained: As well, the way the current First Nations policing policy is written, it's very difficult at times to know who has the first responsibility. It talks about on reserve, where there is supposed to be a federal responsibility and they pay the lion's share of 52% yet when you talk to the province, the province says, policing is a provincial jurisdiction and therefore what we say goes. There's always this jurisdictional battle and then what's the role of the First Nation? The first nation is stuck in the middle saying, hold on a second here, we're talking about policing our community, our people, what do we have to say? It creates this mechanism where it creates a dispute on many levels.[114] On this note, witnesses from Public Safety Canada advised the Committee that the federal government is engaged in discussions with the provinces and territories on the future of the FNPP to determine the kinds of investments to make to ensure that it is meeting the needs of First Nations communities, and to look at how it might need to evolve to better meet those needs. Furthermore, the Committee heard that First Nations communities are being consulted in a series of meetings with the federal government as part of the Economics of Policing initiative to allow them to help shape the evolution of the FNPP in Canada, and to participate very directly in the evolution of the shared framework of the strategy for policing in Canada.[115] Consequently: RECOMMENDATION 4 The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada continue to work with Aboriginal and First Nation leaders to build upon the results achieved through the First Nations Policing Program, continue to facilitate the sharing of best practices, and to explore opportunities to share training infrastructure. PART 4: MOVING FORWARDA. Innovation in the Delivery of Police ServicesCanada is not alone in having to address the spiralling costs of policing. Other countries, such as the U.S. and the U.K., are facing similar cost increases: “Public expenditure on policing in the United States, for instance, more than quadrupled between 1982 and 2006.”[116] Witnesses have emphasized the importance of addressing rising police costs in Canada in a planned and well-considered manner that avoids some of the drastic responses applied elsewhere: We certainly have seen U.S. cities that have gone bankrupt, and we’ve seen states in the U.S. that have had to make 20%, 30%, or 40% cuts to their policing budgets within a matter of months. The U.K. is going through a process of a cut of 15% to 20%, depending on the police service.[117] In the U.S., Los Angeles Police eliminated 600 civilian staff in one year. Phoenix Police stopped recruitment and held 400 positions vacant. Newark Police laid off 170 sworn officers and 210 civilians and demoted 110 officers. Illinois State Police cut more than 20% of their sworn officer personnel. Those are but a few of the many examples throughout the United States.[118] 1. Redefining Core ResponsibilitiesThroughout this study, witnesses highlighted the difficulties stemming from the current policing framework, including the absence of a clear definition of the roles and responsibilities of each level of government in policing. A key aspect of this efficiency and effectiveness reform is the management of public expectations about when, where, and how police services are delivered. Witnesses stressed the importance of properly defining core policing functions. Whereas police forces have proudly responded to each and every call for service by dispatching an officer to attend, this can no longer continue.[119] Chief Constable Bob Rich of the Abbotsford Police Department made the following analogy: The image I want to put before you is that of the 1950s: if you got sick, you phoned the doctor, and he actually came to your house with his little leather medical bag and checked you out. He made a house call. That's what police officers are doing for virtually every call, and it's an outdated and overly expensive way to respond to many calls for service.[120] The redefinition of core policing services is taking place within the RCMP, which has recently modified its core Federal Policing enforcement strategy, described to the Committee as “Federal Policing Re-Engineering”. Under this new enforcement strategy, RCMP Federal Policing will move away from enforcement focused on the elimination of crime related to specific commodities such as drugs, counterfeit goods, or intellectual property, towards greater effectiveness by focusing on the threat posed by particular criminal organizations in order to dismantle them. This strategy was described by RCMP Superintendent Angela Workman-Stark, Director of Federal Policing Re-engineering, as an approach that adopts a broader view of the actual threat, which will lead to greater effectiveness.[121] The Committee encourages police services not to lose sight of the impact that redefining core responsibilities can have on smaller police services in the country, particularly in light of the fact that provinces and municipalities may be left to assume additional policing costs and responsibilities. Professor Griffiths emphasized the importance of effective community involvement before deciding what the police should and should not be doing.[122] Kimberley Sharkey, Deputy Mayor for the City of Brooks, Alberta, illustrated how community involvement in that city has innovatively shifted some responsibilities from the RCMP to two city employees through the creation of city crime prevention and diversity coordinator positions. They have found that this approach provides the most efficient use of policing time and dollars.[123] Consequently: RECOMMENDATION 5 The Committee encourages governments responsible for the administration of policing to work together to seek consensus in defining the core policing duties in Canada, and consider what services currently executed by police forces could be better done by other governmental and non-governmental organizations. 2. Multiple Agency IntegrationPolice services are embracing collaboration amongst partnering agencies, whether law enforcement or otherwise, with a view to increasing efficiencies. Chief Knecht of the Edmonton Police Service advised the Committee that, although in recent years, police services have increased their ability to integrate their services with those of their partners, there is much opportunity for enhanced integration.[124] RCMP Deputy Commissioner Mike Cabana described how the work of the Canadian Integrated Response to Organized Crime (CIROC), a joint initiative of the CACP and the Criminal Intelligence Service Canada, has moved towards operational coordination in the fight against organized crime: Over the course of a number of years, the work of CIROC evolved to the point where we now have a single threat assessment, but the discussion has evolved to the point where agencies are actually working together to disrupt these threats. Whether they are local in nature, whether they are interprovincial or international, what we’ve seen by sharing the information to the level we’re sharing it now is that even those local threats do have, at the very least, an interprovincial linkage. I’ll give you an example. We have an ongoing project, currently, that involves 28 different police services and 56 different investigations that are being coordinated through CIROC. Already the results are unprecedented. It is beginning to achieve the long hoped for goal of true operational coordination between local, municipal, and federal enforcement agencies.[125] The RCMP is also a partner in the Combined Forces Special Enforcement Unit, an eight-agency collaboration bringing together multiple organizations to tackle persistent threats. In addition, the RCMP has deployed resources internationally to work with foreign partners in detecting and preventing illegal migrant vessels from embarking on the dangerous journey towards Canadian shores, likely saving lives and preventing the need for costly domestic investigations.[126] Geoff Gruson, Executive Director of the Police Sector Council, informed the Committee that one particular area in which enhanced integration efforts would be beneficial is in the investigation of cybercrime, given its international aspects: The interesting point of the study we did with Interpol was to understand the fact that you’re dealing with criminality that works globally, yet every single country is trying to develop its own unique solution, its own unique approach. I think that’s one of those areas where it’s really clear we have to integrate, collaborate, and understand the issue, and understand the solution to the response to that issue.[127] The Edmonton Police Service is working closely with the RCMP because Edmonton is surrounded by areas policed by the RCMP. They are currently examining the potential of cost savings through the sharing of a helicopter, a tactical team and an emergency response team.[128] A successful integration initiative was developed in the Yukon, where the correctional centre deals with RCMP cellblock services.[129] In this way, a higher degree of care can be provided out of the correctional centre for certain detainees, such as people with mental health issues. In Saskatchewan, the provincial government is examining the entire corrections system, including the transport of prisoners and overnight operations. Deputy Minister Dale McFee, Corrections and Policing, Government of Saskatchewan, spoke of how many police agencies have moved health staff into their cellblocks to mitigate risk, since upwards of 80% to 95% of detainees have addictions and 30% of these detainees also have mental health issues.[130] There are some real opportunities here, but it’s a paradigm shift in thinking, just like everything else. It’s a new way of approaching it, and it’s really important for us that we’re doing it based on evidence and focused on outcomes.[131] In light of the above: RECOMMENDATION 6 The Committee recommends that police forces consider greater inter-agency cooperation with respect to the sharing of facilities and equipment and integration of staff from the health and policing sectors in certain circumstances. 3. Operational ReviewsOperational reviews examine the efficiency of police services in order to make operational changes in view of enhancing service delivery. This can provide the opportunity to reinvest resources into more proactive policing and new models of community safety. The CPA recently conducted a review of Winnipeg Police Service (WPS) operations that led to concrete recommendations to reallocate resources based on the identification, firstly, of a huge need for more police officers on the street and, secondly, of approximately 90 tasks currently done by police officers that could be performed by civilian personnel. There was no need to hire more police officers or increase the WPS budget; it was just a question of reallocating available resources. In funding this review, it is the intention of the CPA that it serve as a model for other polices forces.[132] Witnesses described how the use of outside specialists who possess the skills and background to assess organizational efficiency has led to the elimination of inefficiencies. The Abbotsford Police Department (APD) recently contracted with KPMG[133] to conduct an efficiency study. KPMG proposed a new intelligence-led policing model based on directing the right resources to the right jobs, with better-quality customer service, clear workflow policies, increased supervision and better performance management. As a result of the review, the APD is introducing a new operations control branch staffed by police officers, community safety officers and civilians, which will direct the use of resources on a daily basis. The unit will handle the low-priority calls for service (approximately one-third of the calls) over the telephone or through an appointment with a police officer at the police station. The goal is to increase the ability of patrol officers to respond more quickly to higher-priority calls and allow patrol officers to have more time to be involved in proactive solutions to reduce crime in the community.[134] The services of KPMG were also used by the Staffordshire Police in the U.K., where police service delivery was re-engineered through the scrutinizing of every task. This review went beyond the traditional consultancy and outsourcing uses of private sector resources: it provided added value by actually building up a review capacity within the police service, allowing it to continue the evaluative work going forward, to avoid future reliance on the consultants.[135] 4. Elimination of Needless DuplicationWitnesses informed the Committee of areas in which the elimination of administrative duplication could achieve cost savings. For instance, reductions are being implemented by the RCMP through administrative and operational support efficiencies;[136] there will now be one pay and benefits office, rather than one in each region of the country.[137] The Committee was also told that the elimination of some of the duplication in police oversight mechanisms, while still maintaining the necessary level of oversight, would improve the job quality of police personnel and introduce important cost savings into the sector.[138] For instance, British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Nova Scotia and Ontario have created independent police investigation agencies. Police complaint commissions also exist in all provinces. The Committee heard that the Province of Quebec is also considering an independent investigation model. The independent investigation conducted by such an agency to determine whether a police officer committed a criminal offence provides value through increased public confidence. Witnesses pointed out that the investigation of the initial occurrence for which the police were called will often be conducted at the same time as the independent investigation that led to the allegation of criminal conduct by the police in their response to the call. The Committee believes there are opportunities to reduce duplication and improve the timeliness of these concurrent investigations through the sharing of evidence. For instance, the Independent Investigations Office of British Columbia has entered into memoranda of understanding with police forces that aim to minimize duplication in areas such as the collection of evidence, the handling of exhibits and the conduct of witness interviews.[139] The Committee also heard that measures to eliminate duplication in police complaint reviews have been included in new federal legislation providing for an integrated public complaints intake system for complaints made to the newly created RCMP Civilian Review and Complaints Commission (RCMP CRCC) and provincial review agencies, as well as the conduct of joint reviews of public complaints by the RCMP CRCC and provincial review agencies.[140] 5. Quality Assurance: Adequacy Standards, Police Qualification and TrainingPolice officers require constant requalification. The Committee heard that traditional in-class and in-person training approaches are costly. It is estimated that of the $12 billion spent annually on policing in Canada, close to $1 billion is related to training. This figure takes into account the indirect costs associated with the delivery of training such as travel, accommodation and the backfilling of positions during officer absences.[141] Despite these significant costs, witnesses appearing before the Committee have observed that there has been little discussion geared toward the identification of potential efficiencies in police training.[142] It is estimated that potential savings are in the range of 10% to 30%.[143] Consequently, witnesses emphasized the need for enhanced research, and a sector-wide approach to the development of the training model of the future.[144] Witnesses have also suggested that there is much scope for improvement in the level of coordination and commonality in the types of training provided and in linking training content to officer competency standards and profiles.[145] The consideration of the effectiveness of police training practices raises the underlying fundamental questions of whether expectations regarding police qualifications have been clearly defined and, in turn, whether the true police training needs have been identified. The Committee heard that expectations with regard to police officer skills vary across the country, with police Acts in each province prescribing varying degrees of police training.[146] Such differences in candidate qualification could have a negative effect on the development of common training standards, leading some witnesses to question whether a national college of policing or a professional designation for policing is needed.[147] In order to address this issue, police forces across Canada have focused on determining the actual skill sets needed to deliver certain police functions.[148] The Committee heard that the Police Sector Council has developed competency profiles providing standards for the duties associated with different police positions, ultimately allowing the realization of efficiencies in human resource management and a better orientation of training needs.[149] Training models must continually evolve and improve to gain efficiencies in order to meet new learner expectations, and to keep pace with the changing needs of front-line police officers.[150] Traditional in-class approaches to police training are not always well-suited to the technology-based learning styles familiar to most new police recruits:[151] They embrace it, and are fully adapted to consuming information and training through technology-based mediums. It’s not simply a preference. Research is showing they actually process information differently than other generations do.[152] The delivery of training through electronic platforms can increase the accessibility, consistency, and cost-effectiveness of training: it can provide anywhere, anytime access; course materials can be prepared once and used repeatedly; new subject-matter experts are not required each time a course is given, and the training is delivered in a consistent manner.[153] Sandy Sweet, President of the Canadian Police Knowledge Network (CPKN), described how that organization is playing a significant role in introducing innovation into police e-learning.[154] Created in 2004, the CPKN is a non-profit, financially self-sufficient organization that partners with the police community to develop and deliver cost-effective e-learning in the Canadian police and law enforcement sectors. Its Board of Directors includes police sector leaders from across the country. The CPKN offers approximately 100 courses, many of which are offered in both French and English. It has approximately 75,000 registered users, whereas there are approximately 70,000 front-line officers in the entire Canadian police community. The Committee notes that this level of access to training materials is important to police working in isolated areas as it allows access to training that would normally require travel.[155] Revenues are generated through a model based on the high-volume delivery of low-cost courses. The average cost of one course is less than $25.[156] When considered in combination with the elimination of training travel costs, this model presents considerable economic benefits. Some aspects of police training are well-suited to an online approach, while others are more compatible with traditional in-person training.[157] The Committee heard that even in such instances, however, online training can complement on-site training methods by affording enhanced opportunities for knowledge transfer: What’s really working in general, whether it’s in police services or academies, is a blending of technology and classroom. You don’t eliminate the classroom, but if you’re going to do an interviewing course in a classroom, a lot of police training academies and police services are asking their people to take the online course first. It’s a two-hour course. It gives you all the basics. Then you can come in and talk about interviewing and do some role playing and that sort of thing.[158] Work is currently being undertaken by sector participants, including Public Safety Canada, to build upon the efforts of the CPKN, beginning with a training summit that took place in September 2013 to explore training issues and to help set priorities related to police training and research to build a better approach.[159] The work of the CPKN demonstrates the benefits of taking a strategic, collaborative and sector-wide approach to training development. The CPKN has developed a network of relationships that includes every police service in the country, major police training academies, the CAPB and the CACP. It relies on the police community to identify new topics. As noted by Mr. Sweet, this is an area where inroads can be made through collaboration: The model we’ve created is a best practice, really. In a sector well known for its stove-pipe tendencies and for its jurisdictional rigidity, we’ve been able to break down some of those silos and build courses that work across the country.[160] In light of the above: RECOMMENDATION 7 The Committee recommends that Canada build on its excellent reputation for highly trained police forces through the further integration of e-learning as a cost effective way of executing some of the in-class training required. 6. Revenue GenerationWitnesses cautioned the Committee about the potential for public concern where there could be a real or perceived conflict between police revenue generation initiatives and police responses. Despite this note of caution, witnesses noted good examples of areas in which police services have succeeded with revenue-generating initiatives: · The False-alarm Reduction Program in Vancouver was created through a by-law requiring persons and businesses to obtain permits for their security alarm systems. Under the by-law, the police may refuse to attend an alarm incident generated by an alarm system without a permit. The strategy was undertaken to reduce the need for the police to respond to false alarms on a continuous basis. People are being more responsible as there are consequences to the improper management of alarm systems. This initiative has raised some revenue and has reduced the drain on police resources.[161] · The Cobourg Police Service has also generated revenue by providing third-party criminal record checks requested by certain large corporations. Whenever these companies hire someone, whether it’s in P.E.I. or British Columbia, the Cobourg Police Service will conduct the criminal record check, which generates revenue that is put directly back into the police budget. In 2012, the revenue generated was just over half a million dollars.[162] · The British Columbia government is turning over traffic fine revenues to local governments to help offset the cost of local policing.[163] Therefore: RECOMMENDATION 8 The Committee recommends that police forces continue to consider ways of revenue generation above and beyond government funding, while ensuring no possible conflicts of interest. 7. Tiered Policing: Civilianization and the use of Special Constables, Volunteers and the Private SectorTiered policing exists in many police services and has been described as a pyramid-type structure.[164] The top tier consists of fully sworn and trained police officers who carry badges and guns, have powers of arrest, and so on. The tier below might be special constables engaged in security services. The tier below that might be community safety officers, who do not have the same level of training and may not carry a gun, but who carry out different functions such as neighbourhood engagement, problem solving at the local level and intelligence collection. They work with the community and share information with police officers who come into that community to respond to incidents. The next tier below that might be volunteers, cadets and auxiliary officers with even less training and exercising even more routine functions, such as managing events or securing a site. In Canada, there are approximately 69,539 sworn police officers and approximately 28,220 civilian staff working in police services directly with them.[165] Police services have used civilianization effectively, employing civilian personnel to perform activities ranging from fairly routine basic administrative functions, such as data entry, to much more specialized functions, such as crime analysis and forensics. There are savings that flow from hiring civilian staff, who receive less training and require less equipment than police officers and whose salaries are generally lower than those of police officers. For instance, a special constable working for the OPP receives a salary of $50,000, versus $85,000 for a police officer.[166] The key is finding the right mix of personnel in the context of a particular police service, given its objectives and its community priorities.[167] As described by RCMP Deputy Commissioner Mike Cabana, “[i]t’s about having the right person with the right expertise doing the right things.”[168] Different jurisdictions employ special constables to perform various tasks: