PACP Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

PUBLIC ACCOUNTS OF CANADA 2015INTRODUCTIONA. The Public Accounts of CanadaThe Public Accounts of Canada present the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada. They provide information about the Government’s financial performance over the previous fiscal year, specifically, its revenues, expenditures and budgetary balance—i.e., the difference between revenues and expenditures. They also provide a snapshot of the Government’s financial position at the end of the fiscal year—i.e., its liabilities, assets and the accumulated deficit. The Public Accounts of Canada 2015, which pertain to the 2014–2015 fiscal year, were tabled in the House of Commons on 7 December 2015.[1] The House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts (the Committee) held a meeting on the Public Accounts of Canada 2015 on 19 May 2016. From the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG), the Committee met with Michael Ferguson, Auditor General of Canada, and Karen Hogan, Principal. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) was represented by Bill Matthews, Comptroller General of Canada, and Diane Peressini, Executive Director, Government Accounting Policy and Reporting. Finally, Nicholas Leswick, Assistant Deputy Minister, Economic and Fiscal Policy Branch, appeared on behalf of the Department of Finance Canada.[2] Bill Matthews, Comptroller General of Canada, TBS, explained the type of information that is presented in each of the three volumes of the Public Accounts of Canada: Volume 1 is the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada. What that means is that it's a statement of financial operations, which is what some older people would call an income statement. It's revenues and expenses. […] Volume 2 is where we get back to Parliament and tell them how much money it voted for each department and how much was spent. Volume 2 relates back to the estimates. It's where Parliament gets a chance to see what was voted, how much was spent, and what gets carried forward. Volume III is […] the volume you will not see anywhere in the private sector, where we have additional disclosures and information that is out there for your information.[3] Regarding the detailed information presented in Volume III of the Public Accounts of Canada, Mr. Matthews added the following: This is unique to the public sector. We are reluctant to propose reductions in information, in the interests of maintaining openness and transparency, but if there are things the committee sees, whether it's a threshold that seems too low, or information you truly don't find useful, please let us know when you do your study.[4] B. The Government of Canada’s ResponsibilityThe Government of Canada is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of its consolidated financial statements in accordance with its stated accounting policies—based on Canadian public sector accounting standards—and for such internal control as the Government determines is necessary to enable the preparation of consolidated financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error.[5] C. The Auditor General of Canada’s ResponsibilityThe Auditor General of Canada’s responsibility is to express an opinion about the Government of Canada’s consolidated financial statements, based on his audit conducted in accordance with the Canadian generally accepted auditing standards. These standards require that the Auditor General of Canada comply with ethical requirements and plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada are free from material misstatement.[6] Michael Ferguson, Auditor General of Canada, OAG, reminded the Committee that he only audits Section 2 of Volume I of the Public Accounts of Canada, and that “[u]nless otherwise noted, the information in all other sections of this volume and the two other volumes is unaudited.”[7] FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE AND FINANCIAL POSITIONThe Public Accounts of Canada 2015 outlines the Government’s financial performance during the 2014–2015 fiscal year and its financial position as of 31 March 2015. Some financial highlights include:

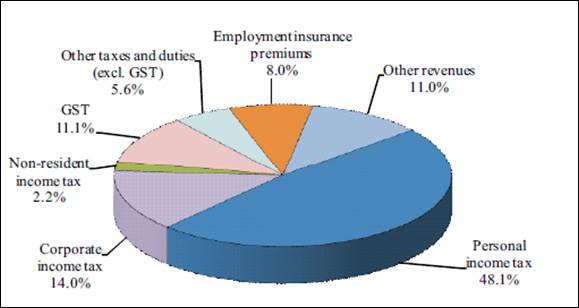

COMPOSITION OF REVENUES AND EXPENSESAs shown in Figure 1, personal income tax revenues were the largest source of federal revenues in 2014–2015, which accounted for 48.1% of total revenues—the same percentage as in 2013–2014.[14] Corporate income tax revenues were the second largest source of federal revenues, which accounted for 14% of total revenues in 2014–2015 compared to 13.5% in 2013–2014.[15] Figure 1 – Composition of Federal Revenues, 2014–2015

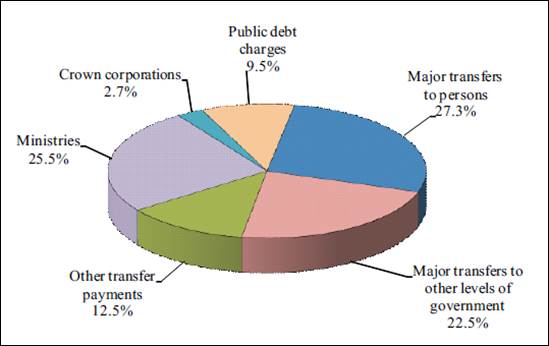

Source: Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2015, p. 1.5. As shown in Figure 2, major transfers to persons—elderly benefits, employment insurance benefits, and children’s benefits—were the largest component of federal expenses in 2014–2015, which accounted for 27.3% of total expenses in 2014–2015 compared to 26.1%[16] in 2013–2014.[17] The second largest component of expenses was ministries (i.e., federal departments and agenices) expenses, which accounted for 25.5% of total expenses in 2014–2015 compared to 25.9%[18] in 2013–2014.[19] Figure 2 – Composition of Federal Expenses, 2014–2015

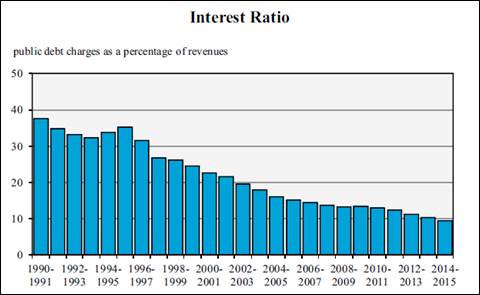

Source: Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2015, p. 1.8. A. Crown Corporation RevenuesDuring its study of the Public Accounts of Canada 2015, the Committee noticed that revenues of Crown corporations increased by 87.5 % from $7.2 billion in 2005–2006 to $13.5 billion in 2014–2015.[20] When questioned about this increase in Crown corporations’ revenues, Mr. Matthews reponded: It is not an increase in the number of crowns, but some of them have increased in size. Particularly, over that period, I would flag for your attention the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, which has certainly grown. If you go back to the recession, for example, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation was used as a vehicle to deliver stimulus to the economy, so there was some growth there. Also, the mortgage business in Canada in general has grown over that period of time. If you are going back 10 years or so, that is the one I would flag as the one that has probably grown the most.[21] Nicholas Leswick, Assistant Deputy Minister, Economic and Fiscal Policy Branch, Department of Finance Canada, added that foreign exchange gains also contributed to this increase, as many Crown corporations hold financial assests in U.S. dollars, which must be expressed as Canadian dollars in the Public Accounts of Canada.[22] In addition, according to Mr. Leswick, the Government of Canada sold about $1 billion of its holdings in General Motors in 2014–2015,[23] which were held in Export Development Canada’s Canada Account.[24] When questioned about whether the Government of Canada is concerned about the increase in Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s (CMHC) balance sheet over the last decade, Mr. Matthews responded that he is not concerned because CHMC operates within its “legal mandates” and “under very strict parameters,” and that this increase “was deliberate growth, if you will, by way of additional programs implemented by the government of the day to increase liquidity in the Canadian financial markets.”[25] Mr. Leswick noted that according to CMHC’s stress testing scenarios,[26] the income statement of the Government of Canada would be protected by CMHC’s reserves even in the event of a U.S. style housing collapse—i.e. a 20% to 30% decline in home prices across the country, and an increase in the unemployment rate from 7% to about 12%.[27] Mr. Leswick also reminded the Committee that the Government of Canada “has acted five times in the housing market since 2012 to effectively condense amortization periods, to increase down payment requirements and so on—credit score requirements—to mitigate any potential housing bubble or adverse housing shock.”[28] B. Accuracy of Budget ProjectionsAccording to the Public Accounts of Canada 2015, the April 2015 Budget underestimated federal revenues by $3.0 billion in 2014-2015, and overestimated federal expenses by $886 million in 2014-2015.[29] When questioned about the accuracy of the Government of Canada’s revenue and expense projections, Mr. Matthews responded: When you look at budget projections, understand that there is a revenue and expense base of roughly $280 billion, depending on the year. Plus or minus $10 billion is a lot of money, but as a percentage it's pretty small stuff. Understand, then, that this is in context, because in the assumptions that we have to make, it's quite possible that you'll see that. If you go back over history, the government has had a better track record in estimating expenses. Revenue is more problematic. The revenue estimates are tougher to do, but the reason varies by year. Some years it's the exchange rate; some years it's corporate taxes. The budget is done typically two months or so before the year starts. In an environment in which the economy is changing rapidly, it is tough to estimate.[30] Answering the same question, Mr. Leswick pointed out that the C.D. Howe Institue prepares a report card for all federal and provincial governments in Canada,[31] and it grades each jurisdiction in terms of transparency and accuracy of their projections.[32] According to Mr. Leswick, the federal government received an A-minus in the most recent report card, which is the second best grade among all jurisdictions.[33] C. Building Canada FundAccording to Infrastructure Canada, the Building Canada Fund was established under the 2007 Building Canada plan to fund infrastructure projects in the three following areas of national importance: a stronger economy, a cleaner environment, and strong and prosperous communities.[34] When questioned about unspent funds earmarked for the Building Canada Fund, Mr. Matthews said: [Y]ou have to negotiate agreements. Once you miss the construction season, if you don't get the agreement in place in time, you've lost the season for the next year. Infrastructure is a notorious lapser. When my colleagues in Finance actually project the budget, they assume a certain amount of lapsing will occur because we want to project the best possible spending. From a departmental perspective, they have to assume the worst-case or best-case scenario, depending on your perspective, to make sure they don't actually overspend what Parliament authorizes.[35] PUBLIC DEBT CHARGESMr. Leswick told the Committee that the public debt charges as a percentage of revenues have been following a downward trend since the 1990.[36] As shown in Figure 3, this percentage decreased form a peak of 37.6% in 1990–1991 to 9.4% in 2014–2015.[37] Mr. Matthews indicated that public debt charges were $27 billion in 2014–2015.[38] Figure 3 – Public Debt Charges, as a Percentage of Revenues, 1990–1991 to 2014–2015

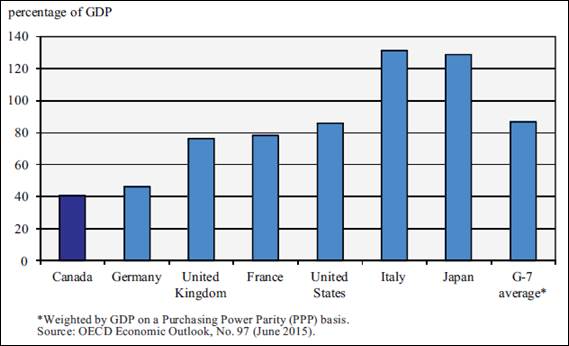

Source: Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2015, p. 1.9. DEBT-TO-GDP RATIO AND DEBT MANAGEMENT STRATEGYThe debt-to-GDP ratio is one of the most commonly used metrics to analyze the evolution of a country’s debt over time or to compare it with that of other countries. The Government of Canada’s Debt Management Strategy sets out its “objectives, strategy and plans for the management of its domestic and foreign debt, other financial liabilities and related assets.”[39] When questioned about the evolution of the Government of Canada’s debt-to-GDP ratio, Mr. Leswick responded: The debt-to-GDP ratio is effectively a crude metric, with debt on top, as we calibrate it. It's just the total accumulated deficit of the federal government over the size our economy. It really just gives an indication to two primary audiences: one is investors, the folks who hold our bonds and expect coupon payments on our debt; and the second is taxpayers. The debt-to-GDP ratio is effectively the general debt dynamics of the country, our ability to service our debt based on the size of our economy. Whereas we had more adverse debt dynamics in the 1990s, through fiscal consolidation efforts on the part of both governments over the last decade and a half, we have gotten our debt-to-GDP ratio down to about 30%. The net debt of the federal government represents 30% of the total size of the economy. It gives you a sense of our ability to service our debt obligations.[40] Mr. Leswick drew the attention of the Committee to a figure presented in the Public Accounts of Canada 2015, which compares Canada’s total government net debt-to-GDP ratio[41] with those of the other G-7 countries (see Figure 4), and then pointed out that “Canada has the best kind of debt dynamics” of all the G-7 countries.[42] For example, in 2014, Canada’s total government net debt-to-GDP ratio was 40.4% compared to an average of 86.8% for the G-7 countries.[43] Figure 4 – G-7 Total Government Net Debt, 2014

Source: Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2015, p. 1.20. When questioned about why the Government did not issue more long-term debt instruments to benefit from the historically low interest rates in Canada, Mr. Leswick replied: I think the member is right: with, effectively, a yield curve that is flatter than at any time in history, why aren't we locking in at lower rates? To some extent we are increasing our volumes at the far end of the yield curve with the introduction of some of our ultra bonds, 50- and 60-year bonds, and borrowing more at the longer end. However, I talked about cost and risk dynamics; it's still cheaper to borrow at the shorter end of the curve. Likewise I have to introduce to you that there are financial market considerations as well. If you issued all your debt at the far end, what would happen is that global pension funds would just buy it all up and hold on to it until maturity. We have to be somewhat conscious about liquidity—repo operations, swaps in financial markets, which really need some of the shorter-term maturities to be able to ensure liquidity of what is AAA paper. I'm on the same track; it's just that there is a multidimensional consideration here.[44] THE AUDITOR GENERAL OF CANADA’S OPINION AND OBSERVATIONSA. Auditor General of Canada’s OpinionFor a 17th consecutive year, the Auditor General of Canada expressed an unmodified audit opinion on the Government of Canada’s consolidated financial statements (as presented in the Public Accounts of Canada 2015).[45] According to Mr. Ferguson: The consolidated financial statements present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position of the Government of Canada as at 31 March 2015, and the results of its operations, changes in its net debt, and its cash flows for the year then ended in accordance with the stated accounting policies of the Government of Canada set out in Note 1 to the consolidated financial statements, which conform with Canadian public sector accounting standards.[46] Mr. Matthews stressed that this17th consecutive audit opinion “testifies to the high standards and quality of the [G]overnment's financial statements and reporting, and is an achievement of which all Canadians can be proud.”[47] B. Auditor General of Canada’s ObservationsIn addition to his audit opinion on the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada, the Auditor General of Canada makes observations on matters that he would like to bring to Parliament’s attention. For the fiscal year ended 31 March 2015, the Auditor General of Canada made one observation regarding the Department of National Defence’s (DND) inventory, and one observation on the liabilities associated with contaminated sites.[48] 1. Department of National Defence’s (DND) InventoryThe OAG has been reporting DND’s challenges in properly recording and valuing its inventory since the Government of Canada first provided a recorded inventory in its financial statements 12 years ago. DND’s inventory “accounts for $6.3 billion [87.5%][49] of the Government’s total inventory of $7.2 billion.”[50] While the OAG noted some improvements—increased awareness and coordination at senior management levels, and additional counts of high value inventory items to support DND’s stocktaking initiative—the OAG continues to estimate inventory errors related to obsolescence and to inaccurate recording of prices resulting in overstatements of inventory in the hundreds of millions of dollars.[51] When asked to provide more details about these improvements, Karen Hogan, Principal, OAG, said: Over the past year we've been happy to see that senior management at [DND] is now much more coordinated and focused together. There's an increased awareness of the concerns and the issues related to inventory. We're happy to see that the public servants and the military are now talking and working toward improving the financial reporting around inventory.[52] The OAG also recommended that DND place more attention on addressing pricing and obsolescence issues.[53] Regarding these issues, Mr. Ferguson said that DND’s senior managers “are beginning to take the steps needed to implement improved financial management controls,” which “reduce the risk of misstating the consolidated financial statements and making decisions without accurate information.”[54] Mr. Matthews informed the Committee that DND is targeting compliance with the Government’s Policy on Internal Control by 2018–2019.[55] When questioned about the reasons why no performance audit has been done on DND’s inventory, Mr. Ferguson responded: To this point we have continued to raise it as part of the audit observations. It's something we can consider, whether there would be more value if we looked at it more in depth in a performance audit. To this point, at least in my memory, we haven't done one, and certainly not in recent years, but we'll take it as a suggestion to consider.[56] When questioned about the impediments that have prevented DND from taking the necessary steps to properly record and value its inventory, Ms. Hogan acknowledged that DND’s inventory is very complex and that the Department has been making some progress, but, according to her, more work is still needed.[57] Mr. Matthews added that DND is the Government’s biggest inventory holder, which is responsible for tracking over 200 million parts, and then explained: [T]his is a systems issue. They had two systems: one to record the inventory and track where it was and a second one that did the pricing. They have recently made some improvements on the systems side, which will help us. The other piece, and the one I'm preoccupied with, is that I care very much about how old the errors are. DND is still tracking parts that date back to World War II. They're in the system. They're probably not relevant anymore. Now, I don't know that; I'm speculating here. I get fussed when I find out that the errors are on new stuff. Are the errors on relatively new purchases or are they on stuff that dates back to 1964? It's the new stuff I care more about. We are in discussions with National Defence. The Auditor General mentioned obsolescence. Maybe there's a certain bucket of parts we should just write off, move on from. Let's be done with those, figure out what's no longer relevant, and just start fresh with the relevant things. That's a massive undertaking itself, but to fix this, I think that's what we need to do.[58] While acknowledging the complexity of the task and the progress accomplished, the Committee is very disappointed by DND’s inability to properly record and value its inventory for each of the past 12 years. The Committee recommends: Recommendation 1 That, by 30 September 2016, the Department of National Defence provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report outlining the concrete actions that it will take to properly record and value its inventory. This report should also provide the timeline for each of these actions. 2. Liabilities Associated with Contaminated SitesIn 2014–2015, a new Public Sector Accounting Standard 3260 (PSAS 3260 Liability for Contaminated Sites) came into effect.[59] Mr. Ferguson explained that the adoption of this standard did not increase the financial liability for contaminated sites because the Government of Canada has been using this standard for the past few years in anticipation of its adoption.[60] However, this standard requires more detailed financial statement note disclosures.[61] According to the OAG, as at 31 March 2015, the Government of Canada had a financial liability of approximately $5.8 billion for the estimated future remediation costs of high- and medium-risk contaminated sites in Canada.[62] Mr. Matthews explained that a financial liability for a contaminated site represents “the present value estimate of the cost to clean up that site to meet current environmental standards.”[63] The OAG noted “opportunities for federal entities involved in managing contaminated sites to improve documentation of key judgements and accounting decisions taken on those sites where contamination exceeds a standard but a liability has not been recorded.”[64] The OAG recommended that the Government of Canada “develop better processes to refine the accounting estimates and record the liabilities associated with contaminated sites at earlier stages of investigation.”[65] Mr. Ferguson also noted that “there was room for improvement in the timeliness and refinement of the estimation process for contaminated sites,” and that “regular updates are required as sites are remediated, as changes in environmental standards emerge, and as estimation techniques improve.”[66] Mr. Matthews cautioned that accounting is not an exact science because it requires estimations and judgement: We talked about estimating the environmental liabilities. You're really projecting what it's going to cost to clean up a contaminated site, and they're all different. Think about something such as veterans' expenses and veterans' liabilities. We are trying to project the eventual cost of caring for our current group of servicemen and servicewomen and existing veterans. There are estimates involved in health care costs, in age, in how many people will take up the services. It is quite a complicated process, and we're always refining those estimates as we learn and get more exposure.[67] When questioned about the $1.2 billion increase in liabilities associated with contaminated sites in 2014–2015, Mr. Matthews responded: When you look at the contaminated sites inventory, changes in evaluation are to be expected. As you clean up sites and further assess things, estimates go up or down. There are roughly 6,600 that we have yet to assess. Understand that we book a liability once we have done an assessment to a certain point where we have some confidence in the number, and that will change over time. If you think about Giant Mine or Faro Mine, that is a very complicated cleanup. As time goes on, the liabilities go up and down. The final point I will leave you with is that the vast majority of our environmental liability really relates to a handful of sites: Faro Mine, Giant Mine, Esquimalt Harbour. I have forgotten their names off the top of my head, but there is one or two more. I think about 65% or 70% of our liability probably relates to four or five sites.[68] When questioned about whether these contaminated sites are publicly or privately owned, Mr. Matthews reponded that the biggest sites used to be owned by private sector organizations, but they became the responsibility of the Government of Canada when these organizations went bankrupt during a time in which “[e]nvironmental standards were quite different” than nowadays.[69] Mr. Matthews then went on to add: I know it's cold comfort to say that we own these things now. That's probably not fair from a “what's just to the Canadian taxpayer” perspective, but at the end of the day this stuff has to be cleaned up and, because of the rules at the time, the Canadian government and the taxpayer are the ultimate risk-holder.[70] Given the size of the liability associated with contaminated sites, the Committee will monitor the Government’s progress in implementing the OAG’s recommendation to “develop better processes to refine the accounting estimates and record the liabilities associated with contaminated sites at earlier stages of investigation.”[71] SECTION NUMBERING FORMAT OF VOLUME II OF THE PUBLIC ACCCOUNTS OF CANADAThe Committee provided some feedback to TBS officials regarding the section numbering format of Volume II of the Public Accounts of Canada which is based on alphabetical order, and thus differs between the English and French versions.[72] For example, the Department of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada corresponds to Section 2 in the English version, but Section 8 in the French version.[73] As one of the main users, the Committee believes that the presentation of the Public Accounts of Canada could be improved by aligning the section numbering in the English and French versions of Volume II of the Public Accounts of Canada. The Committee recommends: RECOMMENDATION 2 That, beginning with the 2015–2016 fiscal year, the Department of Public Services and Procurement Canada align the section numbering of the English and French versions of Volume II of the Public Accounts of Canada. CONCLUSIONIn light of its study of the Public Accounts of Canada 2015 and the testimony it heard, the Committee would like to thank the Auditor General of Canada and his Office for their thorough audit, and congratulate the Government of Canada for receiving its 17th consecutive unmodified audit opinion, which attests that it properly reported its overall financial performance for 2014–2015 to Parliament and to Canadians.[74] SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDED ACTIONS AND ASSOCIATED DEADLINESTable 1 – Summary of Recommended Actions and Associated Deadlines

[1] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2014–2015. [2] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Notice of meeting, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016. [3] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016, 0900. [4] Ibid., 0855. [5] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2014–2015, Volume I, p. 2.4. [6] Ibid. [7] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016, 0845. [8] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2014–2015, p. 1.4. [9] Ibid. [10] Ibid. [11] Ibid. [12] Ibid., p. 1.9. [13] Ibid., p. 1.4. [14] Ibid., p. 1.5. [15] Ibid., p. 1.5. [16] Ibid., p. 1.10.This percentage was calculated as follows: $72,222 million / $276,827 million = 26.1%. [17] Ibid., p. 1.8. [18] Ibid., p. 1.10.This percentage was calculated as follows: $71,728 million / $276,827 million = 25.9%. [19] Ibid., p. 1.8. [20] Ibid., p. 1.23. [21] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016, 0905. [22] Ibid. [23] Ibid. [24] Office of the Auditor General of Canada, “Chapter 5 - Support to the Automotive Sector,” Fall 2014 Report of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2014, p. 5. [25] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016, 0930. [26] For more details about these stress testing results, see Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, 2015 Annual Report, pp. 22-23. [27] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016, 1020. [28] Ibid., 1025. [29] Public Works and Government Services Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2014–2015, p. 1.11. [30] Ibid., 0945. [31] For more details about this report card, see Colin Busby and William B.P. Robson, By the Numbers: The Fiscal Accountability of Canada’s Senior Government, 2015, C.D. Howe Institute, Commentary No. 424, Toronto, 2015, p. 5. [32] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016, 0945. [33] Ibid. [34] Infrastructure Canada, Building Canada Fund. [35] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016, 1010. [36] Ibid., 0935. [37] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2015, p. 1.9. [38] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016, 0935. [39] Department of Finance Canada, 2015–16 Debt Management Strategy, p 3. [40] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016, 0925. [41] “Canada’s total government net-debt-to-GDP ratio includes the net debt of the federal, provincial/territorial and local governments, as well as the net assets held in the Canada Pension Plan and the Quebec Pension Plan.” Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2014–2015, p. 1.20. [42] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016, 0925. [43] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2014–2015, p. 1.20. [44] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016, 0950. [45] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2014–2015, p. 2.43. [46] Ibid., p. 2.4. [47] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016, 0850. [48] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2014–2015, pp. 2.43–2.44. [49] This figure was calculated as follows: $6.3 billion / $7.2 billion = 87.5%. [50] Ibid., p. 2.43. [51] Ibid. [52] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016, 0905. [53] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2014–2015, p. 2.43. [54] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016, 0850. [55] Ibid., 0940. [56] Ibid., 0905. [57] Ibid., 0920. [58] Ibid. [59] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2014–2015, p. 2.44. [60] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016, 0845. [61] Ibid. [62] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2014–2015, p. 2.44. [63] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016, 0955. The present value is the estimated long-term expenses discounted back to the present with discount rates. [64] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2014–2015, p. 2.44. [65] Ibid. [66] Ibid., 0845. [67] Ibid., 0915. [68] Ibid., 0910. [69] Ibid., 0925. [70] Ibid., 1000. [71] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2014–2015, p. 2.44. [72] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 15, 19 May 2016, 0915. [74] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2014–2015, p. 2.43. |