PACP Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

“REPORT 5—CANADIAN ARMY RESERVE—NATIONAL DEFENCE,” SPRING 2016 REPORTS OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL OF CANADAINTRODUCTIONNational Defence is composed of both the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces. Within the Armed Forces, the Canadian Army, including the Army Reserve, conducts land-based missions.[1] As part of the Army’s chain of command, Reserve members are required, like all members of Canadian Armed Forces, “to carry out their missions without reservation, regardless of personal discomfort, fear, or danger.”[2] According to the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG), as of August 2013, the Army Reserve had provided almost half of the Canadian Army’s 40,143 soldiers.[3] The Army Reserve is mostly comprised of part-time professional members of the Canadian Armed Forces, who must balance the demands of their military duties with their civilian lives.[4] In 2013–2014, the cost to train the Army Reserve was about $724 million, with units trained to support both domestic and international missions.[5] Recently, Army Reserve units have been deployed domestically to respond to natural disasters, such as floods and forest fires.[6] Additionally, Army Reserve units have been deployed internationally to places such as Bosnia and Afghanistan.[7] In the spring of 2016, the OAG released a performance audit on “the ability of National Defence to organize, train, and equip its Army Reserve soldiers and units so that they are prepared to deploy as part of an integrated Canadian Army.”[8] On 7 June 2016, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts (the Committee) held a hearing on this audit.[9] In attendance, from the OAG, was Michael Ferguson, Auditor General of Canada, and Gordon Stock, Principal.[10] The Department of National Defence was represented by Bill Jones, Senior Associate Deputy Minister; LGen Marquis Hainse, Commander, Canadian Army; MGen Derek Joyce, Deputy Commander, Military Personnel Command; MGen Paul Bury, Chief, Reserves and Cadets; and BGen Rob Roy Mackenzie, Chief of Staff, Army Reserve.[11] When asked about the reasons for which the Deputy Minister of the Department of National Defence—the designated departmental accounting officer under the Financial Administration Act, as amended by the Federal Accountability Act—[12]was unable to attend the meeting of the Committee, Bill Jones, Senior Associate Deputy Minister, Department of National Defence, apologized on behalf of the Deputy Minister and promised to make him aware of the concern of the Committee.[13] LGen Marquis Hainse, Commander, Canadian Army, Department of National Defence, said that the Canadian Army welcomes the OAG’s audit, and supported the audit team by providing them with more than 1,600 documents over a 10-month period.[14] GUIDANCE ON PREPARING FOR MISSIONSA. Guidance for International MissionsAccording to the OAG, the Army Reserve is expected to provide up to 20% of the soldiers deployed on “major” (large-scale, extended-period) international missions.[15] Thus, after Regular Army soldiers are deployed on the first rotation – up to eight months – Army Reserve units provide about 1,000 trained soldiers for subsequent rotations. Reserve soldiers could be deployed with existing Regular Army units or be part of dedicated Reserve teams of up to 150 soldiers, tasked with some key responsibilities such as influence activities, convoy escort, force protection, or persistent surveillance.[16] The OAG found that although the Canadian Army expects Army Reserve teams to perform specific key tasks, individual Army Reserve units “had not been given clear guidance on the training that is required for the key tasks of Convoy Escort, Force Protection, and Persistent Surveillance until a mission has been identified.”[17] The OAG recommended that National Defence “provide individual Army Reserve units with clear guidance so that they can prepare their soldiers for key tasks assigned to the Army Reserve for major international missions.”[18] National Defence responded that “[g]uidance regarding the required training is provided in the Army’s annual operation plan,” and that “[e]very team is ‘confirmed’ through a deliberate process before being given the green light to deploy.”[19] National Defence also mentioned that the “Army will work toward improving its guidance for anticipated key tasks for major international missions.”[20] In its action plan, National Defence wrote that this work will be completed by 31 March 2017,[21] and provided the following key milestones:

The Committee recommends: Recommendation 1 That, by 31 March 2017, National Defence provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report explaining how the new guidance that it will provide to individual Army Reserve units will help them better prepare their soldiers for major international missions. B. Guidance for Domestic MissionsThe OAG found that the Canadian Army has not defined the domestic mission equipment list that all Army Reserve units should have for training, meaning Army Reserve units may have to rely on other Canadian Armed Forces units to provide this equipment, which can often be unavailable.[26] The OAG also found that between 2013 and 2015, post-domestic deployment analysis revealed many instances in which key equipment was lacking, such as “reconnaissance vehicles, command posts, and communications equipment.”[27] The OAG, therefore, recommended that the Canadian Army “define and provide access to the equipment that Army Reserve units and groups need to train and deploy for domestic missions.”[28] National Defence responded that a “procurement plan is under way to address the shortages within certain fleets.”[29] However, according to the Department: The Canadian Army has defined and provides the equipment required to conduct domestic operations. The majority of this equipment is held either within the unit or with the Canadian Brigade Group. When a specific requirement or gap is identified that is not within the Brigade Group, the Division will reallocate from within its own resources or will request additional items from national stocks.[30] In its action plan, National Defence stated that this commitment will be completed by December 2019, and provided the following key milestones:

When asked whether the lack of equipment for some Reserve units is due to insufficient funding, LGen Hainse responded: Mr. Chair, we are working with the budget that has been given to us right now, so I have no indication whether we're going to have an increase or a decrease. […] Priority will always be given to those units that have a responsive role, and I refer here to those territorial battalion groups. […] When we feel they don't have the necessary equipment, equipment will be pooled from the various brigades to give those units priority. […] But as was pointed out by the Auditor General, we have to do better in making sure that all of the units have at least the minimum requirement for vehicles and minimum requirement for communications, and this is part of our action plan to take account of what all of the units have at this point. That will need to be dealt with according to priority along with the other competing resources.[35] LGen Hainse also noted that the Canadian Army planned to purchase minor equipment such as civilian vehicles for territorial battalion groups for Summer 2016.[36] The Committee recommends: Recommendation 2 That the Canadian Army provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with an interim report on its progress in meeting its first three milestones by 31 January 2017, and a final report explaining how the equipment shortages identified were fully addressed by 31 December 2019. C. Formal Confirmation that Army Reserve Groups Were Prepared to Support Domestic MissionsFinally, the OAG learned that Reserve groups did not have to formally confirm in writing that they were prepared to support domestic missions; specifically, the OAG found that “some brigade groups did formally confirm that they were prepared to support domestic missions whereas others did not.”[37] The OAG recommended that the Canadian Army “require Army Reserve groups to formally confirm that they are prepared to support domestic missions.”[38] National Defence responded that the “Canadian Army will review the process and develop a better-documented confirmation method.”[39] In its action plan, National Defence clarified that the Canadian army will “[d]evelop a formal annual confirmation method for the Territorial Battalion Group (TBG), Arctic Response Company Group (ARCG) and Independent Domestic Response Companies” by 31 March 2017.[40] The Department also provided the following two milestones:

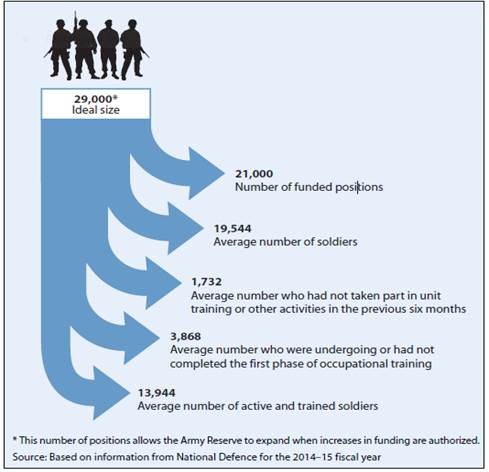

The Committee recommends: Recommendation 3 That, by 31 March 2017, the Canadian Army provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report outlining its formal annual confirmation method for domestic missions. SUSTAINABILITY OF ARMY RESERVE UNITSA. Size of the Army ReserveAccording to the OAG, National Defence has determined that the ideal size for the Army Reserve would be 29,000 positions, which would allow the Reserve to expand when increases to funding are authorized.[42] Figure 1 shows that out of an ideal size of 29,000 soldiers, the Canadian Army had 13,944 active and trained soldiers in 2014–2015. Figure 1 – Various Metrics for the Army Reserve, 2014–2015

Source: Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG), “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” 2016 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, Exhibit 5.4, p. 11. The OAG also noted that the Canadian Army had budgeted $334.9 million for about 21,000 Army Reserve soldiers for the 2014–2015 fiscal year.[43] Thus, the Reserve was funded for about 72% of its ideal size.[44] To better understand the various metrics about the size of the Army Reserve, the Committee asked the following question: If we're able to achieve the 20% number of reservists for major international missions with only 14,000 active and trained, why is it that 21,000 army reserve soldiers is considered to be the goal of DND and the Canadian Army? In response, LGen Hainse provided the following: Mr. Chair, 21,000 is based on the number of units we currently have, and the number of units we currently have is based on historical data, legacy data. Those units happen to be where they are, not based on our history. We feel that there are a lot of positive sides to having those units, even if some of the units are not totally filled. We added up the number of persons we have in all of the units and made an average of the personnel showing up in the historical data and came up with 21,000. If you were to add the complements of the numbers, that is, of units that were filled totally, you would come up with the number 29,000, but this is not what we're funded for, and it is not what the reality has been in the last decade or so. The figure of 21,000, then, is based on historical data.[45] As the Committee was not satisfied with the clarity of this response, the Committee recommends: Recommendation 4 That, no later than 120 days after the tabling of this report, National Defence provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a letter clarifying the preceding response about various metrics for the size of the Army Reserve. The OAG also observed that for the same fiscal year, the average number of soldiers in the Army Reserve was 19,544, of whom 1,732 had not taken part in unit training or other activities in the previous six months; and, 3,868 of whom were undergoing (or had not completed) the first phase of their occupational training.[46] Consequently, about 70% of Reserve soldiers—3,944 on average—were trained and attended unit activities in the previous six months (please see Figure 1 on page 12).[47] LGen Hainse reported that, as of 15 May 2016, the Army Reserve had: 18,550 serving members. However, approximately 1,287 of that number have not attended training in the past 30 to 180 days. Currently, 4,082 of that number are undergoing basic training to reach the initial employment standard. This leaves around 13,181 reserve soldiers trained and available for operation.[48] Regarding the decrease in the number of Army Reserve soldiers from 19,544 to 18,550 between 31 March 2015 and May 2016, Mr. Ferguson, Auditor General of Canada, pointed out that: [W]e both agree that you can look at a number of soldiers, and we had 19,500, but then we said only 14,000 of them were trained. Now we're hearing it's 18,500 with 13,200 trained. The issue is that there has been another decline of 1,000 soldiers in that time period.[49] B. Number of Army Reserve SoldiersThe OAG found that between the 2012–2013 and 2014–2015 fiscal years, the size of the Army Reserve declined at an annual rate of about 5%—or about 1,000 soldiers.[50] Moreover, the OAG also noted that in addition to Reserve units having difficulty with retention of soldiers, National Defence had not recruited the required number of reservists. Officials stated that the latter is due to the fact that the current Reserve recruiting system is ineffective: “it is too slow and does not recruit the number of Army Reserve soldiers it needs, given the present rate of attrition.”[51] Michael Ferguson told the Committee that it will be difficult for National Defence to achieve its goal to increase the Army Reserve by 950 soldiers by 2019.[52] For his part, MGen Derek Joyce, Deputy Commander, Military Personnel Command, Department of National Defence, agreed that it will be difficult to meet this goal, but stressed that the Canadian Army is committed to working towards it.[53] LGen Hainse informed the Committee that the Canadian Army is developing a more streamlined recruiting process that would allow new soldiers to be on the armoury floor within 60 to 90 days after the beginning of the recruiting process.[54] In response to questions about the Canadian Army’s retention and recruiting strategies, MGen Joyce added: [W]e're looking at creating better mobility between the regular force and the reserve force [because] if we improve that flow, then we actually improve the retention of both regular and reserve forces. We're also looking at the compensation and benefit structure for the reserves and the regular force, with the objective of aligning the two and using it as a strategic enabler to have a compensation/benefits structure that is going to be attractive to Canadians to join either the regular force or the reserve force. We're looking at current management as a key element, because that can be either a satisfier or a dissatisfier, regardless of whether you're in the reserve force or the regular force. We're looking at family support, because that's key to retaining any individual in the Canadian Armed Forces. We're looking at mental health and wellness, of course, and we're looking at diversity. Diversity is a key element.[55] The OAG also found that a retention strategy for the Army Reserve has not been developed by National Defence.[56] Therefore, the OAG recommended that National Defence “design and implement a retention strategy for the Army Reserve.”[57] National Defence responded that it will develop and implement an Armed Forces retention strategy, which will offer greater mobility between Regular and Reserve Force.[58] In addition, “[w]hile consideration will be given to transactional requirements in the areas of compensation and benefits, National Defence will develop effective measures including, but not limited to, career management, family support, mental health and wellness support, and diversity requirements.”[59] In its action plan, National Defence stated that this commitment will be completed by 30 September 2018, and provided the following key milestones for the four strategy development phases:

The Committee recommends: Recommendation 5: That National Defence provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with an interim report on its progress in meeting its action plan’s first two milestones by 31 January 2018, and a final report assessing the effectiveness of its retention strategy by 30 September 2019. C. Terms of ServiceAccording to the OAG, part-time Army Reserve soldiers serve and train on a voluntary basis; thus, it is impossible for unit commanders to know if all their soldiers will participate in scheduled activities, such as training.[64] The OAG also observed that “Army Reserve soldiers (and any other Reservists) may accept contracts for full-time service with their units, with Army headquarters, or elsewhere in National Defence.”[65] These contracts can range from 180 days to three years, and can be renewed for much longer periods.[66] The OAG found that this practice is inconsistent with the National Defence Act, “which states that Primary Reserve members are enrolled for other than continuing full-time military service when not on active service undertaking emergency duties for the defence of Canada or deployed on international missions.”[67] In so doing, National Defence has, in the opinion of the OAG, “created a class of soldiers that does not exist in the Act.”[68] Moreover, such soldiers receive 85% of the salary and reduced benefits compared to those in the Regular Army.[69] Mr. Ferguson told the Committee that the Canadian Army “spent about 27% of its overall budget for Army Reserve pay and operating expenses on these full-time contracts, leaving less available for other Army Reserve activities.”[70] When questioned about why these full-time contracts represented such an important percentage of the overall budget of the Army Reserve, BGen Rob Roy MacKenzie, Chief of Staff, Army Reserve, Department of National Defence, explained: There are the two components: the part-time reserve, and those in full-time service that support the unit activity very heavily. Each unit, one of our 123 units, has a cadre of full-time staff, regular army and full-time reservists as support. There are a few numbers in each. Those people are absolutely critical to designing and supporting all the logistics in preparation for the training on a day-to-day basis when the part-time folks come in. That's why it is a fairly substantial chunk of the funding.[71] In light of these findings, the OAG recommended that National Defence “review the terms of service of Army Reserve soldiers, and the contracts of full-time Army Reserve soldiers, to ensure that it is in compliance with the National Defence Act.”[72] National Defence responded that the “Canadian Armed Forces will review the framework for the Reserve Force terms of service and the administration of Reserve Force Service to ensure it complies with the National Defence Act and the regulations enacted under it.”[73] In its action plan, National Defence stated that this review will be completed by 30 September 2017.[74] Therefore, the Committee recommends: Recommendation 6 That, by 30 September 2017, National Defence provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a detailed report explaining how it reviewed the terms of service of Army Reserve soldiers, and the contracts of full-time Army Reserve soldiers, to ensure that it is in compliance with the National Defence Act. D. Medical CareAccording to the OAG, “National Defence policy requires Canadian Armed Forces personnel to report any injury, disease, illness, or exposure to toxic material, whether it is service-related or not.”[75] The OAG observed that over the 2012–2013 to 2014–2015 fiscal years, Reserve soldiers filed about 3,250 medical reports.[76] A study of 846 of these reports found that 35% of incidents happened during training events and 37% happened during physical fitness activities.[77] The OAG found that for Reservists, access to medical care was unclear.[78] For example, if Reserve soldiers “injure themselves during physical fitness training to meet Canadian Armed Forces fitness requirements, Canadian Armed Forces’ medical services do not always provide for care unless that training was formally pre-approved by their commanding officer.”[79] The OAG recommended that National Defence “review its policies and clarify Army Reserve soldiers’ access to medical services.”[80] National Defence responded that the “Canadian Forces Health Services Group Headquarters is actively advancing a number of initiatives to review and support policies for medical assessments that contribute to Primary Reserve soldiers’ overall readiness for training and deployment, and that clarify access to medical services, including:

In its action plan, National Defence wrote that these commitments would be fully implemented in the 2017–2018 fiscal year.[84] LGen Hainse told the Committee that “[c]ommuniqués have been issued throughout the health services chain of command so that all medical facilities understand their responsibility to provide health care services to reservists.”[85] The Committee recommends: Recommendation 7 That, by 31March 2018, National Defence provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report explaining how it has clarified the Army Reserve soldiers’ access to medical services. E. Information about Qualifications Needed for DeploymentAccording to the OAG, National Defence maintains the Personnel Readiness Verification system, which captures soldiers’ current qualifications that are required for deployment. For this audit, the OAG obtained the system’s reports that listed the following levels of qualification for Reserve soldiers in December 2015:

The OAG observed that the system does not record “civilian” qualifications such as language and cultural skills, which Reserve soldiers could bring to the Canadian Army when they are deployed.[87] Furthermore, the OAG learned that the information recorded in the system was neither up to date nor reliable,[88] and found that Reserve units were not updating the system due to a “heavy burden of administrative tasks.”[89] Mr. Ferguson reported that National Defence told the OAG that “the information from this system could not be relied upon.”[90] Consequently, the OAG believes that “the Canadian Army does not have the assurance that Army Reserve soldiers have the current qualifications that they need to be prepared for deployment.”[91] The OAG recommended that National Defence “ensure that it has up-to-date information on whether Army Reserve soldiers are prepared for deployment. This information should include civilian qualifications held by Army Reserve soldiers.”[92] National Defence responded that “work is ongoing through the Military Personnel Management Capability Transformation project to maintain all Reserve Force personnel readiness using the future military personnel management tool, Guardian.”[93] In its action plan, National Defence noted that the first release of Guardian—which excludes availability and self-service capabilities—is scheduled for May 2017, and that the initiative will be fully completed on 31 January 2022.[94] The Department also explained that “Guardian will incorporate the ability for all military personnel, including Reserve soldiers, to include in their Service Record civilian qualifications and a means to query and extract the information for decision making by commanders using self-service capabilities.”[95] After acknowledging that the current military personnel management system is cumbersome and insufficient for the needs of the Canadian Army, MGen Joyce noted: We need a modern HR tool and, as I mentioned earlier, that is being shepherded by the military personnel management transformation HR software, the Guardian project. Over the next six years we're going to see four different releases that will incrementally improve our ability to pull in and report on regular data.[96] When questioned about the rationale for the timeline of 31 January 2022, MGen Joyce responded: Mr. Chair, I want to point out the fact that this is not necessarily a review that we are talking about. It is a major upgrade to our human resource software. The project is called military personnel management capability transformation. Essentially, it is an upgrade from PeopleSoft 7.5, which is what we currently use, to PeopleSoft 9.1 or 9.2. That is why the project length reaches out to 2022. There are a number of interim releases that are going to be let out to the Canadian Armed Forces during that period, the first release coming up in the spring of 2017, in May 2017, which will see a technological upgrade of the HR system to include 9.1.[97] When asked whether the OAG was satisfied with this answer, Mr. Ferguson said: I think there are a number of aspects of the answer that raised some questions. I'm satisfied overall with the answer. I think there are a couple of things to be aware of. First of all, the problem we were raising in the report was that the data from the existing system couldn't be relied upon. I understand that a new system is going to be put in place, but it's not just a system. There's already been a system. There need to be the appropriate controls, the appropriate quality assurance, and that type of thing to make sure the information is properly captured, or we end up just putting another system in place that ends up having the same problems.[98] The other thing, […] is [the] move from Peoplesoft 7.5 to Peoplesoft 9.2 which […] means that PeopleSoft version 9.2 already exists. […] [U]sually a strategy with IT systems is to make sure those upgrades are put in place on a regular basis, so you don't end up with a big project of going from a release that is older and maybe even not supported to the most recent release […] rather than having updated it along the way.[99] National Defence committed to provide the Committee with written answers to the following questions:[100]

The Committee expects responses to these questions no later than 120 days after the tabling of this report. The Committee recommends: Recommendation 8 That National Defence provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with an interim report on its first release of its military personnel management tool called Guardian by 30 June 2017, and a final report outlining the type of reliable and up-to-date information that it has on Army Reserve soldiers’ pre-deployment preparedness no later than 31 January 2022. F. Annual Army Reserve FundingAccording to the OAG, since 2000, the Canadian Army has budgeted annual funding for the Army Reserve based on each soldier participating in unit activities for 37.5 days per year, along with another seven days of collective training (with other units).[101] The OAG observed that local Army Reserve unit activities expected to be covered by the 37.5 days of funding include:

The OAG found that “the budgeted annual funding for the Army Reserve is not consistent with the actual activities undertaken by Army Reserve units.”[103] For example, according to the OAG, in 2013, “an internal Canadian Army analysis was presented for information purposes to senior Army officers, showing that the 37.5 days was at least 10 days fewer than what Army Reserve units actually used for individual and collective training and other activities.”[104] The OAG recommended that National Defence “ensure that budgeted annual funding for Army Reserve units is consistent with expected results.”[105] After stressing that the “Canadian Army assigns resources to ensure that all mandated tasks are funded,” National Defence, responded that it “will monitor whether these tasks are consistent with the results expected of them.”[106] In its action plan, National Defence stated that the “Canadian Army has commenced a review of the Army Reserve Funding Model and will have it implemented for 1 April 2017.”[107] The Department also provided the following key milestones:

When asked whether 37.5 days of funding per year is consistent with the actual activities undertaken by Army Reserve units, BGen MacKenzie responded: [W]e're undertaking a complete funding model review to address this. We started various working groups this past year, with consultation through our divisions and right down to the Canadian brigade group level, so the 10 Canadian brigades that command the reserve units across the country, with their comptroller staff, as well as their deputies, to figure out exactly the best balance based on activities that we've done historically, to look at this model and improve it for the future. We also want to include a better breakdown between our reserve pay and the operation and maintenance, so we want to move soldiers and equipment around the country to get the right balance.[109] BGen MacKenzie then suggested that, while the exact number of days will only be known when this review is completed, the Canadian Army could increase the funding to about 40 to 50 days.[110] The Committee recommends: Recommendation 9 That, by 31 March 2017, National Defence provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report outlining the results of its review of the Army Reserve Funding Model. G. Financial Reallocation and ReportingThe OAG found that in the 2014–2015 fiscal year, “the Canadian Army reallocated $8.2 million in unspent funds from the Army Reserve budget for other purposes within the Canadian Army and returned another $5.3 million of the planned budget of the Army Reserve to National Defence.”[111] However, the OAG also learned from Reserve units that many training needs were not being met, including equipment, ammunition, travel, and administrative support.[112] In response to questions about these reallocated funds, BGen Mackenzie said: This past year all the funding was spent by the army reserve program. In previous years we were unable to spend it with our reserve units, so it was reallocated with proper prioritization within the rest of the army.[113] According to the OAG, National Defence reported to Parliament that “it spent $1.2 billion to train and operate the Primary Reserve in the 2013–14 fiscal year.”[114] Of this amount, per the Canadian Forces, $724 million was to train and operate the Army Reserve; of that amount, $166 million was allocated to the Reserve to operate Canadian Army bases.[115] The OAG found that this amount was calculated based on a ratio of Reserve soldiers to Regular Army soldiers, and not on the use of base facilities.[116] Additionally, the OAG noted that the Canadian Armed Forces does not keep data pertaining to the Reserve’s actual use of base facilities, and thus contends that “the $166 million estimate is not well supported and may result in providing incorrect information to Parliament by overstating the reported expenses of the Primary Reserve.”[117] When asked whether National Defence provided incorrect information to Parliament by overstating these expenses, Bill Jones responded that he believes that the Department has always provided correct information to the best of its ability.[118] According to the OAG, in 2015, the Chief of the Defence Staff directed that an account be used to record what funding is allocated and spent by each Reserve Force.[119] Additionally, National Defence also plans to implement a separate reporting process that will link assigned funding to expected results.[120] Thus, the OAG recommended that National Defence “complete planned changes to the way it reports its annual budgets and the expenses of the Army Reserve, so that National Defence can link assigned funding to expected results.”[121] National Defence responded that, beginning on 9 February 2016, “expenditures related to the Reserve Program were incorporated in the financial reports briefed to senior management.”[122] According to the Department, this “approach will provide greater visibility on funding and expenditures, and will support enhanced reporting and performance measurement.”[123] In its action plan, National Defence described the final expected outcomes as follows:

LGen Hainse stated that the new Corporate Fund Structure will ensure “the transparent allocation of funding for the reserve program,” because “[m]oney cannot be repurposed out of that account unless doing so is sanctioned by the Deputy Minister or the Chief of the Defence Staff.”[127] In light of the evidence it heard and the action plan it reviewed, the Committee believes that National Defence will fully complete its planned changes to the way it reports its annual budget and the expenses of the Army Reserve by achieving the last milestone outlined in its action plan in mid-July 2016,[128] and thus made no specific recommendation on this issue. TRAINING OF ARMY RESERVE SOLDIERSA. Support to Attend Training CoursesAccording to the OAG, Army Reserve soldiers can attend training courses; this can be done through training modules, simulation training, and distance learning to help Reserve soldiers better integrate this training with their civilian schedules.[129] However, the OAG found that from 2011 to 2013, “47 training courses were cancelled, 23 because of a lack of candidates.”[130] National Defence has noted that legislation that protects the employment status of Reserve soldiers—who may require absences from civilian employment for military training or duty—differs across the country.[131] Moreover, the OAG found that federal legislation does not provide this protection for all Army Reserve training; for example, the Canada Labour Code and the Reserve Forces Training Leave Regulations allow absences for some types of training, but not for all types of occupational skills training.[132] Therefore, the OAG recommended that National Defence “work with departments and agencies that have responsibility under the Canada Labour Code and the Reserve Forces Training Leave Regulations to consider including coverage of absences to attend all types of occupational skills training into the Code and the Regulations.”[133] National Defence responded that it “will consult with the Public Service Commission of Canada and other applicable agencies to determine whether changes to federal job protection legislation can be justified.”[134] In its action plan, National Defence stated that, by 15 February 2017, it will provide a recommended way forward to its partners “to incorporate and synchronize provisions within the Canada Labour Code and the Reserve Forces Training Leave Regulations that would specifically encompass coverage of absences to attend occupational skills training into the Code and the Regulations.”[135] The Committee recommends: Recommendation 10 That, by 28 February 2017, National Defence provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report outlining the results of its consultations with other federal departments and agencies to determine whether changes to federal job protection legislation are justified. B. Compensation for EmployersAccording to the OAG, in November 2014, National Defence announced plans of a program to compensate civilian employers and self-employed Reserve personnel to help offset costs incurred by a Reservist’s absence due to deployment; the compensation is about $400 per week of absence.[136] However, the OAG found that the program did not compensate employers when a Reservist attends occupational skills training; thus, it is unable to support the full participation of Reserve soldiers in training for Army missions.[137] The OAG, therefore, recommended that National Defence “consider amendments to its proposed Compensation for Employers of Reservists Program to include absences for all occupational skills training of Army Reserve soldiers.”[138] National Defence responded that, once the original program is fully implemented and institutionalized, the Department will “undertake an evidence-based feasibility study on the expansion of the Compensation for Employers of Reservists Program to include leave for occupational and career training courses, including associated training activities required for career progression.”[139] In its action plan, National Defence noted that this study will be completed by 15 February 2017, and provided the following key milestones:

The Committee recommends: Recommendation 11 That, by 28 February 2017, National Defence provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report outlining the results of its feasibility study on the expansion of the Compensation for Employers of Reservists Program. C. Training Programs for Individual Occupational SkillsAccording to the OAG, the Canadian Army has tried to align standards for individual occupational skills training received by both Reserve and Regular Army soldiers so that all soldiers can achieve the same level of competence for a particular skill.[143] However, the OAG found that initial occupational courses for Reservists led to fewer professional and leadership skills than those for the Regular Army counterparts.[144] The OAG also observed that “Army Reserve soldiers are trained for a specific occupation, such as infantry, armour, artillery, logistics, communications, or electrical mechanical engineering.”[145] However, the OAG found that this training was limited to a narrower set of occupational skills than that which is provided to Regular Army soldiers.[146] The OAG also found that that this lack of individual occupational skills training continued through later career courses. Lastly, the OAG also found that infantry soldiers in the Army Reserve received 25% fewer days of formal individual skills training over their careers than did their Regular Force counterparts.[147] Mr. Ferguson mentioned that he found that these skill gaps were not generally addressed by pre-deployment training.[148] LGen Hainse told the Committee that, “[b]eing part-time, the reserve force will be trained to the same standard, but not to the same breadth as the regular force,” and that “[a]dditional preparative training just prior to deployment will always be required.”[149] D. Training for Deployment on International MissionsAccording to the OAG, the Canadian Army recognizes that gaps in pre-deployment training of Army Reserve soldiers for international missions must be addressed.[150] This is noted in a “2014 inquiry into a 2010 training incident in Afghanistan in which four Army Reserve soldiers were injured and one was killed.” These casualties took place during training on a particular weapon that was part of the mission’s equipment but was not included in pre-deployment training.[151] According to the OAG, the inquiry concluded that “the lack of this pre-deployment training contributed to this incident.”[152] According to the OAG, Canadian Armed Forces soldiers began to deploy as part of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) collective defence in Eastern Europe.[153] From examining pre-deployment training records for one rotation, the OAG found that Army Reserve soldiers had completed training on a range of weapons, but for another rotation, confirmation existed only for personal weapons.[154] In both cases, a gap remained in the weapons training between Army Reserve and Regular Army soldiers before they deployed on international missions.[155] The OAG recommended that National Defence “ensure that training of Army Reserve soldiers for international deployments addresses all known gaps in individual occupational skills training.”[156] In response, National Defence argued that the “Canadian Army already provides sufficient detail to ensure that Army Reserve soldiers are trained to the level required for employment on domestic and international missions.”[157] The Department then stated that the “Canadian Army will ensure the training records of individual soldiers are kept up to date and will continue to explore ways to minimize all known skill gaps.”[158] In its action plan, National Defence noted that this commitment will be completed by 31 March 2017, and provided the following key milestones:

LGen Hainse acknowledged that the Canadian Army “might not have kept some of the data up to date in understanding exactly what was done,” but reassured the Committee: [T]hat every time any organization is deployed on an operation, the commanders have to do an operational declaration directly to me. They put their signature at the bottom that the training indeed has been done, and we have all the details of that generic training that was done by all of the soldiers. When soldiers deploy in an operation, they are as trained as their regular forces counterparts.[164] The Committee recommends: Recommendation 12 That, by 1 June 2017, National Defence provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report assessing its action plan’s effectiveness in addressing all known gaps in individual occupational skills training. E. Collective TrainingAccording to the OAG, the Canadian Army has identified the importance of soldiers training to work together in larger teams of up to 150 soldiers or more, with several types of equipment.[165] The OAG found that “Regular Army units train to this level to have all the skills they require for fighting as an integrated team that can quickly adapt to various combat situations,”[166] but that Reserve units train for fewer skills, in smaller teams, with less access to equipment.[167] The OAG also found that in meeting their collective training requirements, some “Reserve units did not follow the Canadian Army’s requirement that all training be both progressive and safe.”[168] The OAG also found inconsistencies with the process used to confirm whether Army Reserve units had achieved the required level of training.[169] Consequently, the OAG contends that “without a consistent and documented confirmation process, the Canadian Army does not have full assurance that all Army Reserve units have achieved the level of collective training they need to progress to higher levels of collective training, including pre-deployment training for international missions.”[170] F. Integrating Army Reserve Training with Regular Army TrainingThe OAG found that the collective training requirements for Reserve units were not integrated into the Regular Army’s three-year training cycle.[171] Canadian Army analysis from 2015 concluded that this integration would ensure that the Reserve’s training for domestic and international missions would not only be conducted in a progressive and predictable manner, but would also provide formal confirmation of that training.[172] The analysis further noted that this type of training would increase the retention of Army Reserve soldiers.[173] As noted previously, according to the OAG, the Army Reserve is expected to provide up to 20% of soldiers deployed on major international missions, wherein Reserve soldiers are deployed as either individuals placed in Regular Army units, or in Army Reserve teams.[174] However, the Canadian Army has also determined that most of these key tasks would have to be performed by Regular Army soldiers during the initial rotation, due to Reserve units not having been integrated into the Regular Army’s training plan to prepare for Canada First Defence Strategy missions.[175] According to the OAG, in 2009, “the Canadian Army took steps to integrate the collective training of Army Reserve and Regular Army units in the same Division. This integration was to be achieved by linking units that perform the same combat operations – for example, Army Reserve infantry units with Regular Army infantry units.”[176] These pairings were to enhance command and control relationships and joint training, which would ensure that Reserve units were trained to meet assigned tasks.[177] However, the OAG found that, with the exception of artillery units, this has not yet happened.[178] Therefore, the OAG recommended that National Defence “improve the collective training and integration of Army Reserve units with their Regular Army counterparts so that they are better prepared to support deployments.”[179] National Defence responded that the “Canadian Army is taking the necessary steps to develop opportunities for stronger integration between the Regular Army and the Reserve Force.”[180] In its action plan, National Defence noted that this commitment will be completed by 31 March 2018, and provided the following key milestones:

When asked about the steps that have been taken by the Canadian Army to improve collective training and integration between the Regular Army and the Reserve Force, LGen Hainse explained that: [W]e are looking at more integration with the various units. It is true that from an artillery point of view, it has always been a lot easier, because there are fewer of those units around, and they have a complement gun system to do it. When you talk about the infantry, which I can use as an example, it is a bit more complicated because there are a lot of those units. There are more units on the reserve side than there are on the regular forces, so they have to make choices, and they have to be proactive in terms of doing some combined training. What we have done, and the directions that have been given for the next couple of years, is to ensure first and foremost that there exists a link between the reserve units and their regular forces counterparts, and that they create a training plan to work together in order to do some combined training.[183] The Committee recommends: Recommendation 13 That National Defence provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with an interim report on its progress in meeting its action plan’s first milestone by 1 April 2017, and a final report assessing its action plan’s effectiveness in improving the collective training and integration of Army Reserve units with their Regular Army counterparts by 31 March 2018. CONCLUSIONIn this audit, the OAG concluded that “Army Reserve units lacked clear guidance on preparing for international missions, had lower levels of training as cohesive teams, and had not fully integrated this training with that of the Regular Army.”[184] The OAG also concluded that “although Army Reserve units received clear guidance for domestic missions, the Canadian Army did not require Army Reserve groups to formally confirm that they were prepared to deploy on domestic missions,” and that “Army Reserve units and groups did not always have access to key equipment.”[185] Finally, the OAG concluded that “the Army Reserve did not have the number of soldiers it needed and lacked information on whether soldiers were prepared to deploy when required,” and that “Army Reserve soldiers received lower levels of physical fitness training and were not trained in the same number of skills as Regular Army soldiers.”[186] The Committee was very disappointed with the overall impression resulting from this audit that Army Reserve soldiers are currently treated as “second-class” soldiers compared to Regular Army soldiers. Given that soldiers from both the Regular Army and the Army Reserve could be deployed on a major international mission to defend Canada’s security, interests, and values, the Committee strongly encourages National Defence to ensure that Army Reserve soldiers get the training, equipment, and support they need as well as the respect they deserve. The Committee will closely monitor National Defence’s implementation of its action plan to ensure that it properly addresses each of the issues identified in the OAG’s audit. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDED ACTIONS AND ASSOCIATED DEADLINESTable 1 – Summary of Recommended Actions and Associated Deadlines

[1] Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG), “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 1. [2] Ibid. [3] Ibid. [4] Ibid. [5] Ibid. [6] Ibid. [7] Ibid. [8] Ibid., p. 2. [9] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Notice of meeting, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 June 2016, Meeting 18. [10] Ibid. [11] Ibid. [12] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Protocol for the Appearance of Accounting Officers as Witnesses before the Standing Committee on Public Accounts, March 2007, p. 4. [13] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 June 2016, Meeting 18, 0855. [14] Ibid. [15] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 5. [16] Ibid. [17] Ibid. [18] Ibid. [19] Ibid., p. 6. [20] Ibid. [21] National Defence’s Action plan, provided to the Committee on 6 May 2016, p. 1. [22] Ibid. [23] Ibid. [24] Ibid. [25] Ibid. [26] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 7. [27] Ibid. [28] Ibid., p. 8. [29] Ibid. [30] Ibid. [31] National Defence’s Action plan, provided to the Committee on 6 May 2016, p. 2. [32] Ibid. [33] Ibid. [34] Ibid. [35] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 June 2016, Meeting 18, 0930. [36] Ibid., 0900. [37] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 8. [38] Ibid. [39] Ibid. [40] National Defence’s Action plan, provided to the Committee on 6 May 2016, p. 2. [41] Ibid. [42] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 10. [43] Ibid. [44] Ibid. [45] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 June 2016, Meeting 18, 0915. [46] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 10. [47] Ibid. [48] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 June 2016, Meeting 18, 0900. [49] Ibid., 1035. [50] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 10. [51] Ibid., p. 12. [52] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 June 2016, Meeting 18, 0850. [53] Ibid., 0955. [54] Ibid., 0900. [55] Ibid., 0945. [56] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 12. [57] Ibid. [58] Ibid. [59] Ibid., p. 13. [60] National Defence’s Action plan, provided to the Committee on 6 May 2016, p. 3. [61] Ibid. [62] Ibid. [63] Ibid., pp. 3-4. [64] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 13. [65] Ibid. [66] Ibid. [67] Ibid. [68] Ibid. [69] Ibid. [70] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 June 2016, Meeting 18, 0850. [71] Ibid., 0925. [72] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 13. [73] Ibid., p. 14. [74] National Defence’s Action plan, provided to the Committee on 6 May 2016, p. 4. [75] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 14. [76] Ibid. [77] Ibid. [78] Ibid. [79] Ibid. [80] Ibid. [81] Ibid. [82] Ibid. [83] Ibid., pp. 14-15. [84] National Defence’s Action Plan, provided to the Committee on 6 May 2016, p. 4. [85] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 June 2016, Meeting 18, 0905. [86] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 15. [87] Ibid. [88] Ibid. [89] Ibid. [90] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 June 2016, Meeting 18, 0850. [91] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 15. [92] Ibid., p. 16. [93] Ibid. [94] National Defence’s Action plan, provided to the Committee on 6 May 2016, p. 6. [95] Ibid. [96] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 June 2016, Meeting 18, 0925. [97] Ibid., 0905. [98] Ibid., 1005. [99] Ibid. [100] Ibid., 1010. [101] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 17. [102] Ibid. [103] Ibid. [104] Ibid. [105] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 17. [106] Ibid. [107] National Defence’s Action plan, provided to the Committee on 6 May 2016, p. 6. [108] Ibid. [109] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 June 2016, Meeting 18, 0930. [110] Ibid. 0935. [111] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, pp. 17–18. [112] Ibid., p. 18. [113] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 June 2016, Meeting 18, 0925. [114] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 18. [115] Ibid. [116] Ibid. [117] Ibid. [118] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 June 2016, Meeting 18, 1000. [119] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 18 [120] Ibid. [121] Ibid. [122] Ibid. [123] Ibid. [124] National Defence’s Action plan, provided to the Committee on 6 May 2016, p. 7. [125] Ibid. [126] Ibid. [127] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 June 2016, Meeting 18, 0900. [128] National Defence’s Action plan, provided to the Committee on 6 May 2016, p. 7. [129] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 21. [130] Ibid. [131] Ibid. [132] Ibid. [133] Ibid. [134] Ibid. [135] National Defence’s Action plan, provided to the Committee on 6 May 2016, p. 7. [136] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 21. [137] Ibid. [138] Ibid., p. 22. [139] Ibid. [140] National Defence’s Action plan, provided to the Committee on 6 May 2016, p. 8. [141] Ibid. [142] Ibid. [143] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 22. [144] Ibid. [145] Ibid. [146] Ibid. [147] Ibid. [148] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 June 2016, Meeting 18, 0855. [149] Ibid. [150] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 23. [151] Ibid. [152] Ibid. [153] Ibid., p. 24. [154] Ibid. [155] Ibid. [156] Ibid. [157] Ibid. [158] Ibid. [159] National Defence’s Action plan, provided to the Committee on 6 May 2016, pp. 8-9. [160] Ibid., p. 9. [161] Ibid. [162] Ibid. [163] Ibid. [164] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 June 2016, Meeting 18, 0940. [165] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 25. [166] Ibid. [167] Ibid. [168] Ibid. [169] Ibid. [170] Ibid. [171] Ibid, p. 26. [172] Ibid. [173] Ibid. [174] Ibid. [175] Ibid. [176] Ibid. [177] Ibid. [178] Ibid. [179] Ibid. [180] Ibid. [181] National Defence’s Action plan, provided to the Committee on 6 May 2016, p. 9. [182] Ibid., p. 10. [183] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 June 2016, Meeting 18, 0910. [184] OAG, “Report 5–Canadian Army Reserve–National Defence,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 27. [185] Ibid. [186] Ibid. |