PACP Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

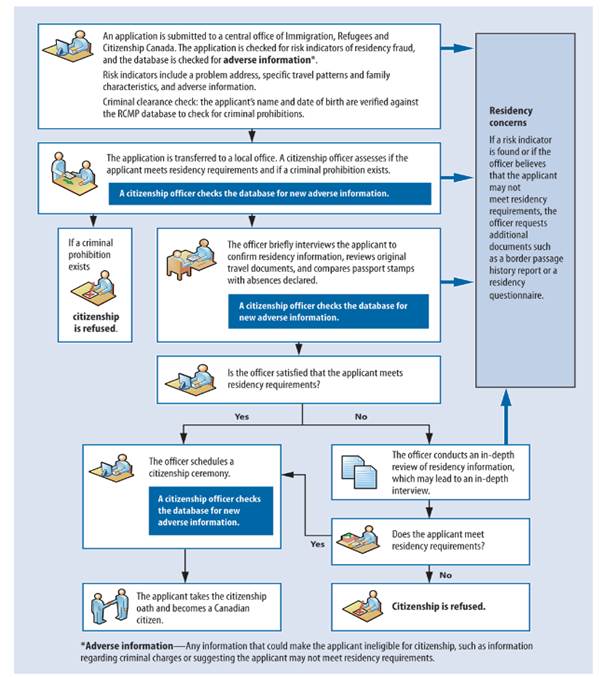

“REPORT 2—DETECTING AND PREVENTING FRAUD IN THE CITIZENSHIP PROGRAM,” SPRING 2016 REPORTS OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL OF CANADAINTRODUCTIONImmigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) is the federal department responsible for ensuring that everyone who is granted citizenship does so in accordance with the Citizenship Act.[1] In 2014, over 260,000 persons became Canadian citizens, an increase of over 100% from the previous year.[2] According to the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG), citizenship applicants, generally, must be permanent residents, and must also meet criteria such as a minimum time lived in Canada, knowledge of an official language, and knowledge of Canada.[3] Applicants must also be free of any criminal prohibitions, defined as circumstances involving crime that can preclude someone from obtaining citizenship—for example, being in jail, on parole, or on probation; having previous convictions; or, facing certain charges.[4] Key to assessing citizenship eligibility is verifying the legitimacy of an application (a visual representation of the application process is provided in Figure 1).[5] New fraud is created continually, so the Department must adjust its systems to combat them, because once citizenship has been granted, revoking it after fraud has been discovered is time-consuming and costly.[6] The Department had about 700 revocation cases pending in January 2016.[7] Fraud related to residency, identity, or undeclared criminal proceedings are the three most common reasons for revoking citizenship.[8] Residency fraud “involves pretending to live in Canada to maintain permanent resident status and meet residency requirements for citizenship.”[9] In 2012, IRCC issued a public warning that nearly 11,000 persons were linked to residency fraud investigations.[10] Figure 1 – Summary of the Citizenship Application Process

Source: Office of the Auditor General of Canada, “Report 2 – Detecting and Preventing Fraud in the Citizenship Program,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, Exhibit 2.2, p. 5. In Spring 2016, the OAG released a performance audit that “examined whether [IRCC] detected and prevented fraud in adult citizenship applications to ensure that only applicants who met selected eligibility requirements were granted Canadian citizenship.”[11] The OAG also examined whether the Citizenship Program obtained accurate, complete, and timely information from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) to inform its decisions to grant citizenship.[12] On 2 June 2016, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts (the Committee) held a hearing on this audit. In attendance, from the OAG, was Michael Ferguson, Auditor General of Canada, and Nicholas Swales, Principal.[13] Representing IRCC was Anita Biguzs, Deputy Minister, and Robert Orr, Assistant Deputy Minister of Operations.[14] The RCMP was represented by Brendan Heffernan, Director General, Canadian Criminal Real Time Identification Services, and Jamie Solesme, Officer in Charge, Federal Coordination Center Canada-U.S.[15] Lastly, representing CBSA was Denis Vinette, Acting Associate Vice-President, Operations Branch.[16] APPLYING CONTROLS FOR DETECTING AND PREVENTING FRAUDA. Checking for Problem AddressesAccording to the OAG, to meet the application process’ residency requirements, citizenship applicants are required to submit their address; sometimes they use an address that may be known or suspected to be associated with fraud, known as “a problem address.”[17] When an applicant tries to use a problem address, it should raise a red flag in the IRCC database (the Global Case Management System, or GCMS).[18] The OAG found that citizenship officers “did not consistently have information about problem addresses to support their decisions to grant citizenship. This was due to database factors, such as data entry errors and inconsistent updating.”[19] For example, the OAG examined 150 addresses from a sample of 9,778 applicants, and found that 102 of them had multiple entries in the system due to variations in how they had been entered—one address had 13 variations.[20] This can lead to officers being unable to detect fraudulent applications.[21] The OAG further noted that if an applicant’s address is “flagged” as problematic in the GCMS, IRCC officers should follow additional procedures, such as requesting further evidence to verify that the applicant meets residency requirements.[22] According to the OAG, citizenship officers are instructed to check the GCMS to determine whether an applicant is using an address that has been used by other applicants during overlapping periods of time; if so, officers are to inform IRCC headquarters so that the problem address list can be updated.[23] However, the OAG found that “when information was available in the database, citizenship officers did not consistently act on it.”[24] In light of this situation, the OAG recommended that IRCC “improve its processes to enter and update problem addresses so they can be identified more reliably,” and “establish quality control procedures to make sure citizenship officers implement these processes effectively and consistently.”[25] In response to this recommendation, IRCC stated that the Department has “provided updated guidance to citizenship officers on identifying, entering, and updating problematic addresses in its Global Case Management System so that these problem addresses can be identified more reliably and appropriate action taken. The Department has established quality control procedures and [committed to] undertake a quality control exercise in September 2016 to verify that these processes are being followed.”[26] Additionally, the “Department has already implemented measures to strengthen processes to better flag addresses in its Global Case Management System that have been, or are suspected of being, associated with fraud, so that applications with these addresses receive closer scrutiny.”[27] More specifically, according to the Department’s action plan, IRCC has committed to establishing and implementing “a documented process to systematically enter and update problematic addresses. This documented process will include regular Quality Control verifications to ensure that problem addresses were entered and updated correctly.”[28] On this point, Anita Biguzs, Deputy Minister, IRCC, added that the Department is “trying to make the procedures more consistent in terms of inputting addresses and making it clear that the officers have to use Canada Post guidelines in terms of inputting addresses.”[29] It should be noted, however, that when questioned about the issue of capturing problem addresses and the examples of multiple applicants using the same address, Anita Biguzs explained to the Committee that multiple uses of a common address are not necessarily proof of citizenship fraud, and offered the following additional explanation: You will oftentimes see the same address as being identified because newcomers have gone into this temporary shelter, temporary housing, that is being provided by settlement provider organizations. It doesn't necessarily mean there's been fraud that has been committed, but it's a fact that you have a common address that is used for newcomers coming to Canada.[30] Robert Orr, Assistant Deputy Minister, Operations, IRCC, also spoke of this phenomenon: Other immigrants may recommend a particular address—“This is a good place to live”—and so the same people go to the same addresses. It's normal and explicable why certain addresses continue to appear.[31] Regarding the issue of data input, quality control and use, on 5 May 2016, Michael Ferguson, Auditor General of Canada, told this Committee that one of the “themes that ties a number of [the Spring 2016] audits together is that the data collected by many government organizations is either not usable, not used, or not acted upon.”[32] Furthermore, at the same hearing, he made specific reference to this performance audit and added the following: Some important controls designed to help citizenship officers identify fraud risks were inconsistently applied. Because of weaknesses in the department’s database system, officers did not always have accurate or up-to-date information about addresses that were known or suspected to be associated with fraud.[33] The Committee shares these concerns about data collection, quality, and use, and thus recommends: Recommendation 1 That, by 31 March 2017, the Department of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report outlining its documented process to systematically enter and update problematic addresses and the results of its quality control exercises. This report should also explain how this documented process and quality control exercises will allow the Department to identify problem addresses more reliably and ensure that citizenship officers implement its quality control procedures effectively and consistently. B. Identifying Fraudulent and Altered DocumentsAccording to the OAG, fraudulent citizenship applicants may alter passports and other documents to falsify their residency status in Canada; the OAG examined how IRCC detected such documents.[34] During the examination, the OAG noted inconsistent practices for addressing suspicious documents.[35] For example, the OAG found that in one region, “no documents suspected to be fraudulent have been seized for in-depth analysis since at least 2010; in another, citizenship officers seized problem documents and submitted them to [CBSA] for detailed examination.”[36] The OAG also found that IRCC’s guidance to citizenship officers for dealing with such matters was itself ambiguous, possibly contributing to this inconsistency.[37] For example, this guidance did not clarify the difference between “keeping” and “seizing” a document, nor did it clearly define who was authorized to seize such documents.[38] Moreover, according to the OAG, the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act explicitly gives IRCC and CBSA officers the authority to seize documents; however there is no such provision in the Citizenship Act.[39] Lastly, another similar finding of the OAG was that citizenship officers failed to check travel documents against the Lost, Stolen and Fraudulent Document database, as instructed by departmental guidance.[40] Due to holes in IRCC’s processes for detecting fraudulent documents, not only could perpetrators avoid detection and prosecution, but fraudulent documents may continue to circulate for use by other ineligible applicants.[41] Therefore, the OAG recommended that IRCC “clarify citizenship officers’ authority to seize problem documents, provide officers with more detailed guidance and training, and ensure that officers implement this guidance.”[42] In response, the Department stated the following:

Furthermore, in its action plan, IRCC noted that it had clarified the current authorities to seize documents, updated guidance, and explored opportunities for amendments to the Citizenship Act.[45] The Department also said that it will take the following actions:

The Committee recommends: Recommendation 2 That, by 31 March 2017, the Department of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report explaining its process to track seized documents and its joint training approach with the Canada Border Services Agency. This report should also outline the main results of the Department’s quality assurance exercises on the process of document seizure. Mr. Robert Orr also provided details to the Committee about an international tool to aid officials in detecting fraudulent travel documents, to which Canada has access: What it basically does is outline the security features of passports of most countries of the world, so that if you have a document in front of you, you know that you can look at this particular feature to see whether it's correctly done or not. It's very useful in that respect, when you're not sure whether the document you have is genuine or not.[49] C. Obtaining Information from the RCMP about Criminal BehaviourAccording to the OAG, eligible citizenship applicants cannot have been convicted of certain offences, be incarcerated or be on probation; also, all applicants over 15.5 years of age are subject to a criminal clearance check by the RCMP.[50] Following this check, IRCC requires applicants to self-report any new criminal charges against them before taking the Citizenship oath.[51] Citizenship officers use the GCMS to check whether the RCMP has found any new charges against the applicant at any point in the process.[52] The OAG examined whether IRCC “obtained accurate, complete, and timely information from the RCMP to make informed decisions when granting citizenship.”[53] Specifically, the OAG looked at the process for criminal clearance screening, and the process for information sharing when the RCMP charges a permanent resident or foreign national with a crime.[54] The audit’s focus was on the sharing of information, not on the quality of the information in the national database.[55] According to the OAG, the criminal clearance process begins when an IRCC officer requests a clearance check from the RCMP at the beginning of an application process.[56] The RCMP checks a national database to determine if the applicant has a criminal record; once completed, the clearance remains valid for 18 months. The OAG found that, generally, this process worked well.[57] The OAG also examined whether the RCMP shared complete and timely information about criminal charges it brought against permanent residents and foreign nationals with the Department.[58] The OAG examined a sample of 38 cases where individuals had been charged by the RCMP with a crime, some serious enough to make an individual ineligible for citizenship, and found that the RCMP shared the required information in only two of them.[59] Of the remaining 36 cases in which the RCMP did not share the required information, four were seeking citizenship; in three of these cases, IRCC had no information about the criminal charges.[60] Consequently, two of these applicants received citizenship, and a third applicant could have received it if not for failing the knowledge exam.[61] The OAG contends that a “key reason for the observed gaps in sharing information about criminal charges against permanent residents and foreign nationals is that the RCMP and the Department have not established a process by which to share this information, as is required by their memorandum of understanding.[62] Officers in both departments were not clear on what information they needed to share or when and how to share it.”[63] The result, according to the OAG, is that “the process for sharing information on charges against permanent residents and foreign nationals was ad hoc and ineffective.”[64] According to the OAG, the initial criminal clearance check is completed early in the citizenship application process and IRCC does not have a systematic way to obtain information on criminal charges directly from police forces other than the RCMP; thus, applicants who are criminally charged after passing the initial criminal clearance check may go undetected.[65] For example, of the 42 revocation cases studied, the OAG found that seven individuals had not self-reported criminal charges and eventually obtained citizenship.[66] The OAG suggested that “completing the criminal clearance check at a later stage in the application process may help reduce the risk that individuals with criminal prohibitions will be granted citizenship.”[67] Finally, the OAG found some cases in which IRCC officers had access to information on criminal prohibitions, but did not act upon it, leading to ineligible applicants getting Canadian citizenship.[68] In light of these findings, the OAG recommended that IRCC and the RCMP “revise their procedures to clarify how and when to share information on criminal charges against permanent residents and foreign nationals,” and “review the optimal timing of the criminal clearance process.”[69] IRCC agreed with this recommendation, and stated that it has “engaged the RCMP to review the optimal timing for conducting criminal clearance, while bearing in mind the need to process citizenship applications in a timely manner. The Department has also engaged the RCMP to clarify processes for sharing information about criminal charges that impact citizenship applicants after the initial clearance. This will be completed by 31 December 2016.”[70] For its part, the RCMP responded that it “will examine the appropriate timing for the criminal clearance check during the citizenship application process,” and “explore how and when the RCMP should share information about criminal charges against permanent residents and foreign nationals” by 31 December 2016.”[71] In its action plan, the RCMP also committed to the following:

The Committee recommends: Recommendation 3 That, by 31 March 2017, the Department of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police report to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts the optimal timing for criminal clearance in the citizenship process, and confirm that it has been implemented in their procedures. Recommendation 4 That, by 31 March 2017, the Department of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police report to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts the failsafe process that they have implemented for sharing all information with one another, about all criminal charges against permanent residents and foreign Nationals. C. Obtaining Information from CBSA about Potential Immigration FraudAccording to the OAG, the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act authorizes CBSA to support the Citizenship Program through various activities; this relationship, including the sharing of information with IRCC, is governed by a memorandum of understanding.[73] CBSA’s support activities include:

The OAG states that pursuant to CBSA policy, once officers obtain adverse information that might affect an applicant’s eligibility for citizenship, they must inform IRCC through an alert in the GCMS.[75] As IRCC officers are required to search the system for such alerts, if they find one, they “may decide to carry out additional procedures to make sure the applicant’s residency requirements have been met before granting citizenship.”[76] The OAG examined if the Citizenship Program obtained accurate, complete, and timely information from CBSA to make informed decisions when granting citizenship, and found that the Agency did not consistently provide IRCC with information when permanent residents were linked to fraud investigations.[77] Moreover, the OAG found that when CBSA did provide the Department with pertinent information, it was not always timely—in some cases, the delays were one or two years after the start of an investigation.[78] It should be noted that CBSA officials reported to the OAG that “one reason for this delay is that sharing information too early can compromise an investigation.[79] Another possible reason for the observed gaps is that the Department and the Agency have not established a process that sets out when, what, or how information should be shared.”[80] Thus, without specific procedures in place, CBSA “officers used their own judgment based on the circumstances of the case. As a result, information sharing was inconsistent, and citizenship officers often lacked important information when assessing an individual’s eligibility for Canadian citizenship.”[81] In light of these findings, the OAG recommended that IRCC and CBSA “improve information sharing to ensure that individuals linked to fraud investigations are subject to additional review to confirm their eligibility for citizenship.”[82] IRCC agreed with this recommendation and stated that the Department “has taken active steps to ensure that information on individuals who are linked to immigration fraud be communicated to the Citizenship Program in a consistent and timely manner so it can be used in the eligibility process for citizenship.” IRCC and CBSA have also “clarified the legislative authorities supporting the information sharing needed by the Department to make Citizenship Act eligibility decisions.” Moreover, both “organizations are collaborating to establish clear processes and procedures to ensure the Department receives timely information about fraud investigations. The new processes will be in place by December 2016.”[83] CBSA also agreed with this recommendation, recognizing “the need to share relevant information on immigration fraud with [IRCC] in a timely and accurate manner—without creating a negative impact on ongoing investigations—to help the Department identify individuals who may not be eligible to become Canadian citizens.”[84] Furthermore, in its action plan, the Agency states that it plans to assess:

The Committee recommends: Recommendation 5 That, by 31 March 2017, the Department of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency confirm to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts that the Agency is sharing with the Department all information about immigration fraud investigations into individuals applying for citizenship; and that the Agency do so without jeopardizing those investigations. When questioned about the issues surrounding information sharing between IRCC and both the RCMP and CBSA, Anita Biguzs offered the following: There is other work currently under way, certainly the work with the RCMP and CBSA on information sharing. We have already been in discussion with officials of those agencies to clarify the issue of authorities. We clearly recognize the need to update our memorandum of understanding on information sharing. As I said, our outline in the plan is to have updated information-sharing agreements in place with those agencies by December.[86] Additionally, Inspector Jamie Solesme, Officer in Charge, Federal Coordination Center, Canada-United States, RCMP, explained to the Committee that with regard to the sharing of information, law enforcement agencies must also be mindful of the Privacy Act, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, human rights, etc. Thus, information sharing requires achieving a balance between these provisions and supporting other governmental organizations.[87] MANAGING FRAUD RISKSA. Identifying and Analyzing Fraud Risks and TrendsAccording to the OAG, IRCC’s Program Integrity Framework states that risk management is an ongoing, systematic process of identifying and analysing risks, which requires “developing and thoroughly assessing response options, putting mitigation measures into action, monitoring their outcomes, and readjusting as needed.”[88] The OAG examined whether IRCC had in place a systematic process to identify and analyse risks in its Citizenship Program, including fraud risks.[89] The OAG found that although the Department identified broad categories of fraud risks, it did not adequately capture the information acquired during the application process so as to better understand the types and frequency of fraud.[90] The OAG also concluded that without such understanding, it is impossible to know if a situation improves after implementing mitigation measures.[91] The OAG suggested the following examples of analyses that would be useful to do, but that the Department did not perform:

According to the OAG, IRCC’s Program Integrity Framework recommends that programs should study patterns of program abuse to better identify risk of fraud.[93] The OAG examined whether IRCC’s “risk indicators for residency fraud were based on sound evidence and analysis, as required by its own policies.”[94] The OAG found that although IRCC identified risk indicators associated with residency fraud, it did not have enough data or analysis to support how or why it selected some of them—for example, problem addresses and specific employment characteristics—but not others.[95] The OAG, thus, recommended that IRCC “develop a systematic, evidence-based approach to identifying the risks of fraud, including establishing a baseline and monitoring trends, as required by its Program Integrity Framework.”[96] IRCC agreed with the recommendation, noting that it had implemented a Citizenship Fraud Action Plan to prevent and deter fraud more effectively. The Department also developed risk indicators and other fraud-detection tools and established triage criteria to ensure applicants at high risk of committing fraud are subject to closer scrutiny.[97] The Department also stated that it “developed a Citizenship Program Integrity Framework in January 2016, which outlines a systematic, evidence-based approach to identifying and managing the risks of fraud in the program, including establishing various baselines and monitoring trends.”[98] Additionally, in its action plan, IRCC committed to establishing “a baseline to monitor the refusal rates of files with and without risk indicators as part of the Citizenship Program Integrity Framework. This will be done during the 2016–2017 fiscal year and trends will be monitored annually.”[99] The Committee recommends: Recommendation 6 That, by 31 March 2017, the Department of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report outlining how the Citizenship Program Integrity Framework and its associated baseline were established, and how the Department will monitor the refusal rates of files. The OAG also recommended that IRCC “document its rationale for selecting risk indicators for residency fraud, and ensure that these indicators are checked consistently and are effective at detecting and preventing fraud.”[100] In response, the Department stated that it has “initiated an analysis of the triage criteria by conducting program integrity activities as part of the Citizenship Program Integrity Framework. As part of the framework, the risk indicators will be evaluated to verify they are consistently applied.”[101] More specifically, IRCC’s action plan states that “[v]alidation exercises on the triage criteria indicators will be conducted to ensure the criteria are consistently applied and are effective at detecting and preventing fraud. Each indicator will be reviewed through a program integrity exercise. The exercises will verify that the triage criteria are based on sound evidence and analysis. These activities will begin in the 2016–2017 fiscal year and will be ongoing.”[102] On this point, Anita Biguzs explained the Department’s plan going forward: We will actually substantiate our risk indicators based on that kind of evidence and document it. The intention is that we will be evaluating and re-evaluating the risk indicators on a much more regular basis, but also documenting them, and then establishing a baseline.[103] The Committee recommends: Recommendation 7 That, by 31 March 2017, the Department of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report outlining how it has improved the documentation of its rationale for selecting risk indicators for residency fraud, and the results of its validation exercises. B. Assessing the Effectiveness of Fraud Controls and Making AdjustmentsAccording to the OAG, IRCC’s Program Integrity Framework shows the importance of quality control to discover the extent of program abuse, as well as to improve fraud detection and prevention.[104] The Department has identified three types of quality control exercises:

The OAG examined whether IRCC assessed the “effectiveness of the fraud detection measures it chose to implement and whether it made any adjustments based on the results.”[106] The OAG found that the Department’s local offices regularly conducted quality assurance and quality control exercises to ensure citizenship officers were following procedures.[107] However, the OAG noted that these exercises do not indicate whether fraud controls were applied and working as intended; moreover, the OAG also found that IRCC did not “conduct targeted quality assurance or quality control exercises to make sure officers applied key fraud controls correctly.”[108] Anita Biguzs acknowledged the program’s deficiency in this area: In terms of lessons learned that have come from this, our guidance to officers has had to be improved. We actually always do issue guidance to citizenship officers, but clearly, I think, issues have arisen in terms of consistency across the system.[109] Additionally, the OAG concluded that although IRCC has taken some steps to assess the effectiveness of its risk indicators, additional work is required.[110] For example, according to the OAG, IRCC studied in 2013 the effectiveness of the risk indicators it used to identify higher-risk applications as regards residency; however, the OAG found the sampling methodology employed was not reliable, and that benchmarks were not established to quantify the effectiveness of the indicators.[111] In 2015, the Department also began a preliminary analysis to develop a strategy to assess risk indicators.[112] According to the OAG, the Department created an electronic repository of program integrity exercises that is available to all IRCC staff.[113] However, the OAG contends that although this repository includes data from 250 exercises, their results have not been analysed to determine if any adjustments to fraud controls are needed.[114] The OAG also noted that IRCC had made adjustments to fraud control measures without having analysed if they were applied correctly or were working as intended.[115] For example, the OAG found that the Department had “changed some of the risk indicators for residency fraud without conducting any analysis to determine whether these changes would compromise program integrity, or whether the applications that presented a higher fraud risk would still be targeted.”[116] The OAG contends that due to these changes, “significantly fewer applications were flagged as higher risk and given more in-depth assessment.”[117] Lastly, according to the OAG, IRCC extended the validity period for criminal clearances—from 12 months to 18 months—to improve the processing efficiency of applications.[118] Although the Department concluded that this extension would not compromise program integrity, the OAG found that this conclusion “does not appear to be supported by evidence.”[119] Therefore, the OAG recommended that, in order to ensure continuous improvement in its efforts to detect and prevent fraud, IRCC “monitor its fraud controls to ensure they are applied appropriately and are achieving the intended results,”[120] and that IRCC “should examine the results of its continuous improvement processes regularly and make any needed adjustments to its fraud controls.”[121] In response IRCC stated that it has “established a process by which fraud controls will be monitored regularly to ensure they are being applied appropriately and achieving the intended results […] As well, to ensure continuous improvement in efforts to detect and prevent fraud, the Department created a Citizenship Program Integrity Working Group in August 2015 to disseminate information on emerging fraud trends and best practices for fraud detection and prevention among citizenship offices across the country.”[122] In its action plan, the Department added that, starting March 2017 and ongoing, it will “develop new fraud controls, if required, by examining the results of decisions on citizenship applications through anti-fraud exercises.”[123] Finally, in response to questions regarding the lack of analysis of the data from the 250 exercises noted previously, Anita Biguzs stated the following: We have put in place a systematic, evidence-based approach to identifying and managing risk. It includes quality assurance and quality control. This means we will be doing strengthened analysis activities. We have had our framework validated by an independent third party to make sure that we have checks and balances on what we're doing. We will also be doing exercises as many as three times a year to get the feedback we need as part of our work plan and part of our continuous improvement, which will include random targeting.[124] The Committee recommends: Recommendation 8 That, by 31 March 2017, the Department of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report outlining its process for monitoring fraud controls and assessing whether they are being applied appropriately and achieving intended results. CONCLUSIONIn this audit, the OAG concluded that IRCC “did not adequately detect and prevent fraud to ensure that only applicants who met selected eligibility requirements were granted Canadian citizenship.”[125] Although it is possible for IRCC to revoke citizenship after fraud has been discovered, this process is both time-consuming and costly.[126] Moreover, given the fact that Canadian citizenship provides a number of benefits such as international mobility, access to Canadian rights and privileges as well as financial benefits,[127] the Committee is adamant that IRCC act promptly to ensure that Canadian citizenship is granted only to eligible applicants, and minimize the risk that ineligible applicants can enjoy these benefits, even temporarily, through fraudulent means. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDED ACTIONS AND ASSOCIATED DEADLINESTable 1 – Summary of Recommended Actions and Associated Deadlines

[1] Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG), “Report 2 – Detecting and Preventing Fraud in the Citizenship Program,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 1. [2] Ibid. [3] Ibid. [4] Ibid. [5] Ibid. [6] Ibid. [7] Ibid. [8] Ibid. [9] Ibid. [10] Ibid. [11] Ibid. [12] Ibid., p. 2. [13] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 June 2016, Meeting 17. [14] Ibid. [15] Ibid. [16] Ibid. [17] OAG, “Report 2 – Detecting and Preventing Fraud in the Citizenship Program,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 4. [18] Ibid. [19] Ibid., p. 6. [20] Ibid., Exhibit 2.3, p. 6. [21] Ibid. [22] Ibid., p. 7. [23] Ibid. [24] Ibid. [25] Ibid., p. 8. [26] Ibid. This quotation was edited for clarity about the timeline. [27] Ibid. [28] IRCC Management Action Plan, presented to the Committee on 1 June 2016, p. 1. [29] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 June 2016, Meeting 17, 0900. [30] Ibid., 0905. [31] Ibid., 0905. [32] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 5 May 2016, Meeting 11, 0920. [33] Ibid., 0850. [34] OAG, “Report 2 – Detecting and Preventing Fraud in the Citizenship Program,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 8. [35] Ibid. [36] Ibid. [37] Ibid. [38] Ibid., pp. 8–9. [39] Ibid., p. 9. [40] Ibid. [41] Ibid. [42] Ibid. [43] According to LEGISinfo, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration reported this bill back to the House of Commons on 5 May 2016. [44] OAG, “Report 2 – Detecting and Preventing Fraud in the Citizenship Program,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 9. [45] IRCC Management Action Plan, presented to the Committee on 1 June 2016, p. 2. [46] Ibid. [47] Ibid. [48] Ibid. [49] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 June 2016, Meeting 17, 1020. [50] OAG, “Report 2 – Detecting and Preventing Fraud in the Citizenship Program,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 9. [51] Ibid., pp. 9–10. [52] Ibid., p. 10. [53] Ibid. [54] Ibid. [55] Ibid. [56] Ibid. [57] Ibid. [58] Ibid. [59] Ibid. [60] Ibid., p. 11. [61] Ibid. [62] Ibid. [63] Ibid. [64] Ibid. [65] Ibid. [66] Ibid. [67] Ibid. [68] Ibid., p. 12. [69] Ibid. [70] Ibid. [71] Ibid. [72] Ibid. [73] OAG, “Report 2 – Detecting and Preventing Fraud in the Citizenship Program,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 12. [74] Ibid., p. 12–13. [75] Ibid., p. 13. [76] Ibid. [77] Ibid. [78] Ibid., p. 14. [79] Ibid. [80] Ibid. [81] Ibid. [82] Ibid. [83] IRCC Management Action Plan, presented to the Committee on 1 June 2016, p. 3. [84] OAG, “Report 2 – Detecting and Preventing Fraud in the Citizenship Program,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 14. [85] Canada Border Services Agency, Management Response and Action Plan, provided to the Committee on 1 June 2016, pp. 1-2. [86] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 June 2016, Meeting 17, 0910. [87] Ibid., 0920. [88] OAG, “Report 2 – Detecting and Preventing Fraud in the Citizenship Program,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, pp. 15–16. [89] Ibid., p. 16. [90] Ibid. [91] Ibid. [92] Ibid. [93] Ibid. [94] Ibid. [95] Ibid. [96] Ibid. [97] Ibid., p. 17. [98] Ibid. [99] IRCC Management Action Plan, presented to the Committee on 1 June 2016, p. 4. [100] OAG, “Report 2 – Detecting and Preventing Fraud in the Citizenship Program,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 17. [101] Ibid. [102] IRCC Management Action Plan, presented to the Committee on 1 June 2016, p. 4. [103] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 June 2016, Meeting 17, 1030. [104] OAG, “Report 2 – Detecting and Preventing Fraud in the Citizenship Program,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 17. [105] Ibid. [106] Ibid., p. 18. [107] Ibid. [108] Ibid. [109] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 June 2016, Meeting 17, 0900. [110] OAG, “Report 2 – Detecting and Preventing Fraud in the Citizenship Program,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 18. [111] Ibid. [112] Ibid. [113] Ibid. [114] Ibid. [115] Ibid. [116] Ibid., pp. 18–19. [117] Ibid., p. 19. [118] Ibid. [119] Ibid. [120] Ibid. [121] Ibid. [122] Ibid., p. 19. [123] IRCC Management Action Plan, presented to the Committee on 1 June 2016, p. 5. [124] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 June 2016, Meeting 17, 0920. [125] OAG, “Report 2 – Detecting and Preventing Fraud in the Citizenship Program,” Spring 2016 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Ottawa, 2016, p. 19. [126] Ibid., p. 1. [127] Ibid., Exhibit 2.1, p. 3. According to the OAG, Canadian citizenship provides the main following benefits: few visas needed to visit other countries; no restrictions on entering or leaving Canada; eligibility to vote; eligibility for consular assistance overseas; no risk of deportation; health care and other social benefits; post-secondary education at Canadian rates; and, easier access to certain Canadian jobs. |