PACP Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

PUBLIC ACCOUNTS OF CANADA 2016INTRODUCTIONA. The Public Accounts of CanadaThe Public Accounts of Canada are produced in three volumes:

The Public Accounts of Canada 2016, which pertains to the 2015–2016 fiscal year, were tabled in the House of Commons on 25 October 2016.[2] The House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts (the Committee) held a meeting on the Public Accounts of Canada 2016 on 3 November 2016. From the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG), the Committee met with Michael Ferguson, Auditor General of Canada, and Karen Hogan, Principal. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) was represented by Bill Matthews, Comptroller General of Canada, and Diane Peressini, Executive Director, Government Accounting Policy and Reporting. Finally, Paul Rochon, Deputy Minister, and Nicholas Leswick, Assistant Deputy Minister, Economic and Fiscal Policy Branch, appeared on behalf of the Department of Finance.[3] On 24 November 2016, the Committee also held a meeting to conduct an in-depth review of the Department of National Defence’s (DND) plan to properly record and value its inventory. From DND, the Committee met with John Forster, Deputy Minister, Patrick Finn, Assistant Deputy Minister, Materiel, and Claude Rochette, Assistant Deputy Minister (Finance) and Chief Financial Officer.[4] B. The Government of Canada’s ResponsibilityThe federal government is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of its consolidated financial statements in accordance with its stated accounting policies—based on Canadian public sector accounting standards—and for such internal control as the government determines is necessary to enable the preparation of consolidated financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error.[5] C. The Auditor General of Canada’s ResponsibilityThe Auditor General of Canada’s (AG) responsibility is to express an opinion on the government’s consolidated financial statements, based on his or her audit conducted in accordance with the Canadian generally accepted auditing standards. These standards require that the AG comply with ethical requirements and plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the consolidated financial statements of the government are free from material misstatement.[6] Michael Ferguson, Auditor General of Canada, OAG, stressed that the consolidated statements are a key government accountability document because they “provide a great deal of information that can help parliamentarians understand the results of the government’s financial transactions for the past year” such as, for example, “the financial position, results of operations and changes in financial position of the government.”[7] Mr. Ferguson also noted that the OAG’s “annual audit of the Government of Canada’s consolidated financial statements takes about 50,000 hours of” his staff’s time, “which is more than it takes to complete six performance audits.”[8] FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE AND FINANCIAL POSITIONThe Public Accounts of Canada 2016 outline the government’s financial performance during the 2015–2016 fiscal year and its financial position as of 31 March 2016. Some financial highlights include:

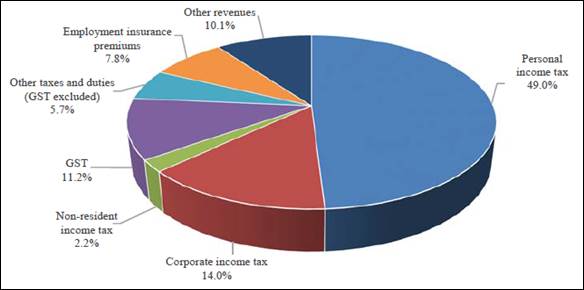

COMPOSITION OF REVENUES AND EXPENSES FOR 2015–2016As shown in Figure 1, personal income tax revenues were the largest source of federal revenues in 2015–2016, which ammounted to 49.0% of total revenues compared to 48.1% in 2014–2015.[15] Corporate income tax revenues were the second-largest source of federal revenues, which accounted for 14.0% of total revenues in 2015–2016—the same percentage as in 2014–2015.[16] Figure 1 – Composition of Revenues for 2015–2016

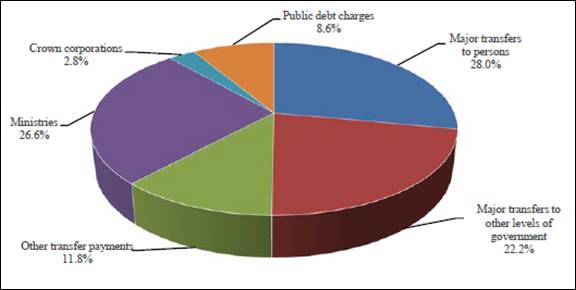

Source: Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2016, Volume I, p. 1.5. As shown in Figure 2, below, major transfers to persons—elderly benefits, employment insurance benefits, and children’s benefits—were the largest component of federal expenses in 2015–2016, which accounted for 28.0% of total expenses in 2015–2016 compared to 27.3% in 2014–2015.[17] The second-largest component of expenses was ministries’ expenses, which accounted for 26.6% of total expenses in 2015–2016 compared to 25.5% in 2014–2015.[18] Figure 2 – Composition of Expenses for 2015–2016

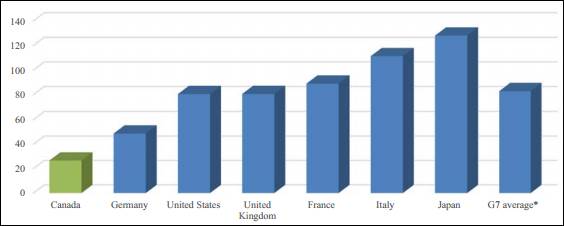

Source: Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2016, Volume I, p. 1.7. VARIOUS SUBJECTS STUDIED BY THE COMMITTEEA. Lapsed Funding and Frozen AllotmentsBill Matthews, Comptroller General of Canada, TBS, explained that lapsed funding is simply “voted funding that does not get spent.”[19] In response to various questions about lapsed funding, Mr. Matthews stated that TBS’s lapsed funds are related to its central votes, which are essentially contingency funds for the entire federal government that are only used if needed—that is, they are not programs.[20] He then explained why the Department of Infrastructure, the Department of National Defence (DND), and Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada also often lapsed funds: With regard to infrastructure, most often you're negotiating agreements with either provinces or municipalities, sometimes both. Because of the way the vote structure works—you have the up-to amounts—departments have to come in with their most optimistic view of the world, and reality never works out quite as fast as their optimistic view of the world […] For DND, it's because of large procurements. The others here are usually involved with negotiations either with provinces or with first nations organizations, and it's those negotiations that typically cause delays. I think the unique thing on infrastructure this year is that the Windsor-Detroit bridge falls under that ministry, and that's a major project that had some lapses.[21] When asked what internal mechanisms ensure that the funds approved by Parliament are not being spent for good reasons rather than because of inefficiency within federal departments or the reluctance by decision makers to do things, Mr. Matthews provided the following: There's a mix of both. What you really have to get to is the results around what their spending was—was it projects that didn't occur, or have they actually come in under budget, as you mentioned? It's those discussions around their forecasts that drive it. The key public document is the quarterly financial statements that departments produce, but frankly, nobody looks at those. They're out there, and you can get some sense of departmental spending. They're public. Internally we have different conversations about what their projected spending is. The quarterly one says what they've spent; internally we have discussions about their projected spending. Partway through the year you would see the government come in with supplementary estimates, if cases of increased spending are planned, but they don't come in with decreased spending. It's really a forecasting piece.[22] Mr. Matthews also drew the Committee’s attention to the information on frozen allotments that TBS began to disclose in 2015–2016: Late in the fiscal year, we now publish when a department has a frozen allotment. I will explain what that means, because it is a bit of a technical term. You can see in public what a department actually has frozen, which is an indicator as to what it's not going to spend. We have the frozen allotment because Parliament votes departments up to amounts, such as up to, say, $100 million for project X, Y, or Z. They don't vote reductions partway through the year. If a department has $100 million in authorized spending and they say they can't spend it all, we don't go to Parliament and ask to please reduce their votes, because it's an up-to amount. As long as they're not going to go over, Parliament has done its thing. Inside the government, though, if we know that National Defence, for instance, isn't going to spend all its money and has asked us if they can spend that money in future years, we need to put a control in place so they don't spend it in both years. That's what's called a frozen allotment.[23] The Committee reviewed the most recent information on frozen allotments and found that, for 2015–2016, the total amount frozen in voted authorities was $5.1 billion as of 12 February 2016. Most of these frozen allotments were due to the planned reprofiling of funds ($2.8 billion) to future years in order to reflect changes in the expected timing of program implementation, and uncommitted authorities in the Treasury Board managed central votes ($1.8 billion).[24] B. InfobaseMr. Matthews talked about TBS’s InfoBase, which is an online tool that members of Parliament and Canadians “can use to look at government spending and other data such as” Human Resources data.[25] He then pointed out that public accounts data has also recently been added to InfoBase.[26] C. Canada’s Total Government Net DebtAs shown in Figure 3, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Canada’s total government net debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 26.7% in 2015—the lowest level among G7 countries, which recorded an average ratio of 83.0%.[27] Figure 3 – G7 Total Government Net Debt-to-GDP, 2015

Source: Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2016, Volume I, p. 1.19. When questioned whether the IMF calculated the total government net debt-to-GDP ratio of each of the G7 countries with the same accounting rules, Mr. Matthews responded that the basic rules are the same, but there are some small differences that the IMF takes into account in its calculations.[28] For example, Paul Rochon, Deputy Minister, Department of Finance, explained that there are two main factors that need to be taken into account for Canada: The first is the federal nature of Canada and the second is the fact that we, unlike many other countries, have a large contributory public pension plan, the CPP and the QPP, so the number that you have here for Canada in the total government net debt comparator is the sum of the debts of the federal government and the provincial governments, less the assets in those two pension plans.[29] D. Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s Stress TestsIn response to questions about the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s (CMHC) stress tests, Mr. Rochon explained that CMHC regularly undertakes stress tests, and publishes their results and the parameters of these tests in its annual report.[30] He then shared the following example with the Committee: There are varying degrees of stress, from what you might think of moderate—for example, a 10% reduction in house prices—to something that's really quite exceptional, such as the last episode in the United States. For a more moderate event like a 10% decline in house prices uniformly across the country, CMHC estimates that its net loss in income in total, cumulatively over a six-year period, would be $2.5 billion.[31] [In the extreme scenario of a U.S.-style housing correction, that] would be significantly larger, closer to $11 billion.[32] E. Accuracy of Deficit ProjectionsIn response to questions about the accuracy of the Department of Finance’s deficit projections, Mr. Rochon stated that, in 2015–2016, “the projected deficit turned out to be $4.4 billion lower than originally estimated in the 2016 budget” because “revenues came in at $4.3 billion higher than” what was projected.[33] He then argued that this projection was very accurate because the error of $4.4 billion is rather small compared to the federal budget of $300 billion.[34] F. Debt Management StrategyThe Debt Management Strategy “sets out the Government of Canada’s objectives, strategy and borrowing plans for its domestic debt program and the management of its official international reserves. Borrowing activities support the ongoing refinancing of government debt coming to maturity, the execution of the budget plan and the financial operations of the Government.”[35] In response to questions about the government’s debt management stragegy, Mr. Rochon explained that the Department of Finance and the Bank of Canada spend a lot of time analyzing the optimal approach to debt management for the Government of Canada: The types of issues we debate and analyze are related to such things as whether in the current interest rate environment, where long-term rates are very low, we should actually structure the debt in such a way as to move more debt out to the longer end of the curve. Considerations in those types of decisions involve things such as the natural trade-off between locking into long-term debt at a time when short-term interest rates are low. Probably more importantly, we know that there is what you could almost think of as a natural hedge between debt charges and revenues. That is to say, when revenues decline because the economy is weak, debt charges also tend to decline, so we balance those considerations in our analysis.[36] G. Debts, Obligations and Claims Written Off or ForgivenWhen asked to confirm that the federal government wrote off, forgave, remitted or waived a total of $4.4 billion in 2015–2016, Mr. Matthews stated that this figure looks accurate,[37] and then explained the following: It varies by year, and I want to make sure the members understand when we say [write-off] or “forgiven”, it's in legislation that it has to be disclosed. The bulk of these numbers come from the Canada Revenue Agency. Is it an abnormal amount? No, but it's not exactly standard year to year either. It depends on their practices. What is normal is the key departments that drive this, and CRA is usually[.][38] […] First of all, my colleague Diane has just informed me that the numbers are relatively consistent with the previous year. Second, on the [write-off] versus forgiveness, “forgiveness” means you no longer owe it. You're off the hook. There are lots of reasons. On the actual [write-off], we still try to collect those figures, but you're dealing with bankruptcies or perhaps people who have left the country, and it's just a matter of wanting to keep the books clean. It's a good thing to put those out there.[39] When asked how parliamentary committees can make sure that the departments use write-offs as a last resort, Mr. Ferguson responded that parliamentary committees should ask different departments to appear as witnesses to explain what they do to collect these funds before some amounts are written off, and then explained the following: When you're dealing with things like [write-offs], obviously the important point is what happens at the very beginning, when they're paying money out in the first place or when there's a loan or there's some reason that people owe money to the government. By the time you get to the [write-off] stage, there's not a whole lot left that can be done. When you're dealing with things like Canada Revenue Agency and the tax side of things, there are always going to be people who end up in bankruptcy or whatever, so there are going to be some of those issues. It's taxes. That's a different situation. However, for some of them, when you're dealing with loans or benefit payments or those types of things, what are those departments doing in the very first place to make sure that only the people who should get those benefits are getting them, or that the people who are getting the loans have the capability to pay them back? I think there's a matter of paying attention to both the front end and the [write-off].[40] H. Public-Private Partnerships’ Impact on the Government’s Consolidated Financial StatementsWhen questioned about the impact of public-private partnerships (P3s) on the government’s consolidated financial statements, Mr. Matthews stated that, although all P3s are different, the impact mainly depends on whether the government owns an asset or not.[41] He then added that in all the cases, the government is often the ultimate risk holder: People talk about P3s being risk-free to government, but you have to look at the deal. The government is the risk holder. More often than not, they end up as an asset on our books, either when it's done or at some point through the project. Generally speaking, they end up as an asset. The Government of Canada has a few P3s. The B.C. government has a lot more and has more experience, but we have some big ones. I'm going from memory, but I think most of them are in our books as an asset.[42] I. Gender-Based AnalysisAccording to Status of Women Canada, gender-based analysis “is an analytical tool used to assess the potential impacts of policies, programs, services, and other initiatives” on women and men.”[43] When asked to what degree federal departments and agencies do gender-based analysis, Mr. Matthews responded the following: I'd just say it's really a question of quality. Things like expenses for national debt aren't going to have gender-based analysis, but real programs should, in theory, all have gender-based analysis. However, I think the quality is the real question.[44] THE AUDITOR GENERAL OF CANADA’S OPINION AND OBSERVATIONS ON THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS OF CANADA 2016A. Auditor General of Canada’s OpinionFor an 18th consecutive year, the AG expressed an unmodified audit opinion on the government’s consolidated financial statements (as presented in the Public Accounts of Canada 2016).[45] According to Mr. Ferguson, this means that Parliament and Canadians “can rely on the information they contain.”[46] Mr. Matthews shared a similar point of view by saying that this “demonstrates once again the high quality and accuracy of Canada’s financial reporting.”[47] He then went on “to recognize the excellent work of the financial community across the Government of Canada,” whose “members are responsible for maintaining detailed records of the transactions in their departmental accounts and strong internal controls.”[48] B. Auditor General of Canada’s ObservationsRegarding the audit of the consolidated financial statements of the government, the AG sometimes makes some observations on matters that he or she would like to bring to Parliament’s attention. For the fiscal year ended 31 March 2016, the AG made four observations on the following subjects: transformation of pay administration, the discount rates for significant long-term liabilities, the Department of National Defence’s inventory and the liabilities for contaminated sites.[49] 1. Transformation of Pay AdministrationAs part of his annual audit of the consolidated financial statements, the AG tests pay and benefits, which together represent one of the government’s largest expenses.[50] According to Mr. Ferguson, the government spent approximately $50 billion on personnel costs in 2015–2016.[51] In 2015–2016, the AG “found payment errors, however, because the transformation initiative was only partially implemented before the end of the fiscal year, the impact of these errors was not material to the consolidated financial statements.”[52] These errors “were overpayments and underpayments of portions of employee pay attributable to input errors and to delays in processing changes in employees’ work arrangements, such as eligibility for a bilingualism bonus and changes in shift-work hours.”[53] The AG finds these errors and delays in processing corrections to employee pay and other pay actions not acceptable given their direct effect on employees.[54] For this reason, he encourages the government to “continue its efforts and quickly address the identified weaknesses in pay administration, in order to pay employees the right amount, on time.”[55] In addition, the AG noted that his office is currently planning the scope of a performance audit that it will undertake on the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative.[56] According, to Mr. Ferguson, this audit will probably be completed by Spring 2018.[57] When questioned about what the government should do to ensure that its employees are paid the salaries they are owed without overpayments or shorfalls, Mr. Ferguson responded that “the government must find ways to manage this problem” by identifying the necessary controls to improve the accuracy of payments.[58] 2. Discount Rates for Significant Long-Term LiabilitiesAccording to the AG the “establishment of reasonable estimates has a direct effect on the quality of the financial information used for decision-making. The consolidated financial statements are a source of this information for Paliament and Canadians.”[59] For 2015–2016, the AG determined that the government’s “estimates and underlying assumptions are within the reasonable range permitted by the Public Sector Accounting Standards.”[60] However, the AG found that certain rates determined by the government “to value significant long-term liabilities are at the higher end of the acceptable range, when compared with market trends.”[61] “Using a higher discount rate yields a lower estimate for long-term liabilities.”[62] For example, a one percentage point decrease in the discount rate used in measuring the accrued benefit obligations of the unfunded pensions would have increased the obligations by $9.6 billion.[63] Mr. Ferguson noted that he supports the government’s ongoing project to update the methodology used to determine discount rates, but he recommended that the government “consider industry practices, emerging changes in accounting standards, and trends in the Canadian financial market as part of this project.”[64] In response to questions about the discount rates that the government uses, Mr. Ferguson explained that the discount rate used for a funded pension plan would be based on the assumed rate of return of its pool of assets, while the discount rate for an unfunded pension plan would be based on the government’s borrowing cost.[65] In light of this testimony, the Committee recommends: RECOMMENDATION 1 That, by no later than 120 days after the tabling of this report, the Government of Canada provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with the planned date on which it will report publicly the results of its project to update the methodology used to determine discount rates, and clearly explain how it will consider industry practices, emerging changes in accounting standards, and trends in the Canadian financial market as part of this project. 4. Department of National Defence’s InventoryDND’s inventory is important to the consolidated financial statements because it is valued at $6.2 billion and represents 86% of the government’s total inventory.[66] The AG has been reporting on DND’s “challenges in properly recording and valuing inventory for 13 years, since the Government of Canada first recorded inventory in its consolidated financial statements.”[67] The issues identified during the AG’s audits over the years are caused “by a combination of quantity errors, failure to write off obsolete items, pricing errors, and misclassification between inventory and asset-pooled items.”[68] According to the AG, DND is making some progress—for example, the new and automated methodology to analyze inventory pricing and obsolescence introduced in 2015–2016—but “the Department must continue its efforts to ensure that inventory is properly recorded in the consolidated financial statements.”[69] The Committee tabled a first report in June 2013 and a second report in June 2016 that both recommended that DND provide it with a plan to record and value its inventory properly. When the Committee compared the 2013 plan and the 2016 plan, it found that the milestones presented in the two plans were different and that some of the deadlines were pushed into the future. Mr. Ferguson reported that DND continues to make “errors in areas of inventory pricing, the identification of obsolete inventory, the misclassification of items, and some quantity errors.”[70] When questioned about DND’s progress in properly recording and valuing its inventory, Mr. Ferguson stated that the OAG has seen some improvements in the way DND tracks the quantity of its inventory, although there are still some problems.[71] For example, DND now analyzes its inventory to try to calculate and record an allowance that accounts for its error rate but, Mr. Ferguson would like to see DND’s inventory “practices improve to the point that” the Department does not need to record an allowance for those types of errors.[72] After acknowledging that DND’s inventory is unique because its inventory is mostly composed of long-term assets that are difficult to value, Karen Hogan, Principal, OAG, acknowledged that over the past years DND has “increased coordination between the public servants and the military” to better record and value its inventory.[73] When asked whether Canada could look at other countries for inspiration to better record and value its military inventory, Mr. Matthews stated that, although we do not “often think about South America in terms of best practices in accounting and asset management,” “Columbia is one of the best countries in the world at tracking its military assets.”[74] He then told the Committee that DND “has recently been put in touch with its counterparts in Colombia to talk about the systems and practices it uses.”[75] John Forster, Deputy Minister, DND, stressed that properly recording and valuing its inventory is a very large and complex problem: Believe me, if it was easy, we would be finished. We have about 640 million items in our inventory, and over 450,000 different codes. In respect of ammunition alone, we have over 5,000 different items, and they're stored in warehouses and bases across the country and around the world. Some of the inventory goes back decades and predates the government's starting to value this and put it on its accounts. Sometimes it's a challenge to put a value on it. Sometimes we're asked, “How hard can it be? Why can't you be like Canadian Tire?” That's true to some extent, and I asked the same question when I first arrived, but there are some key differences. First, most businesses acquire inventory to use it, sell it, and replenish it, so they're always able to update the value of their items. In defence, it's a bit different. We actually often acquire inventory and hold it to ensure that we have inventory and parts in readiness and for emergencies. Sometimes we need to make sure we have a stockpile of older equipment because it may be hard to get parts anymore. We take items out of our inventory to repair them, to fix them, to use them, and then we put them back in. Sometimes it's hard to put a value and a number on it. […] These aren't intended in any way as excuses. It's just our reality. Our inventory is large. It's spread out close to our operations, and it involves tens of thousands of people who are either purchasing, stocking, or using those items and who put in our inventory information.[76] Mr. Forster then described each of the six points of DND’s action plan to properly record and record its inventory as follows: First, on those six points in the action plan, number one is governance. We are making this a priority for the department. Our associate deputy and vice-chief, through a defence renewal committee, oversee it. Our senior leadership have it on their agenda, and a directive from the deputy and the chief have gone out on this. Second, we do want to implement an automated identification technology. That's bar codes and radio frequency identification. We're doing the options analysis. This will be a big change and a big project, and we'll have to look at how fast we can do it and what we can afford. Third, we're changing the accountability of our senior managers. They have to sign attestations each year that they're following our processes, and we do an annual stock-taking. We're trying to work our way through it. To date, we've done about $4 billion worth of our inventory, and we'll do another $1 billion this year, to recount. Fourth, we're trying to modernize our inventory management. We're removing obsolete items and outdated items. We go through some of that every year to get out-of-date codes on stock and write that stock down. It's kind of like cleaning out your attic. We're trying to get through some part of it each year. Fifth, we're reviewing how we price and value our inventory. We want to make sure going forward that we have the right prices. We still have to deal with some of the original legacy prices that were in there, so that's the sixth element.[77] When asked to “provide the Committee with a report explaining how each of the milestones of the 2013 Action Plan were either met, or not met,” and “a report with detailed reasons for why deadlines to the 2013 Action Plan were extended into the future,”[78] DND responded: While [the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces (DND/CAF)] delivered on many of its 2013 Action Plan commitments, integrating multiple businesses into [the Defence Resource Management Information System (DRMIS)] highlighted additional deficiencies in various business processes, which in turn required more resources, effort and time than initially estimated. The migration of data from multiple systems created significant data accuracy challenges for the department. As DND/CAF implemented the 2013 Action Plan, it gained a better understanding of the challenges and nature of DRMIS. DND/CAF’s 2016 Action Plan represents an evolution of the 2013 Action Plan as a result of these lessons learned and of close engagement with allies facing similar challenges in inventory management to deliver sustainable improvement instead of short-term fixes.[79] In this report, DND also noted that in addition to its 2013 Action Plan, “the Department implemented other initiatives to improve inventory management” such as the “Chief of Defence Staff and Deputy Minister Directive on Material Accountability and the Inventory Valuation Initiative.”[80] The Chief of Defence Staff and Deputy Minister Directive on Material Accountability “represents an effort driven by top leaders in the Department to address continuing materiel management and control deficiencies, and to augment the initiatives underway as part of the 2013 Action Plan.”[81] The Inventory Valuation Initiative seeks “to address the conversion of data from the old supply system into DRMIS. In this process, the Department recognized that the valuation of its materiel holdings needed to be corrected. […] By 31 March 2015, this initiative had corrected $1B worth of inventory data.”[82] When asked to “provide the Committee with a clearer explanation of the terms used and make the two charts [2013 Action Plan and 2016 Action Plan] comparable for proper comparison,”[83] DND provided the following: The 2013 Action Plan represented specific actions to address the accuracy of inventory data, with focus on inventory quantity and location. The 2016 Action Plan was built on the lessons learned in the implementation of the 2013 Plan. Indeed, while implementing the 2013 Plan, the Department gained a better understanding of the challenges of moving material data from multiple system applications to DRMIS. Overall, the 2016 Action Plan aims to better integrate efforts to improve inventory management across business lines, facilitated by the use of DRMIS. The 2016 Action Plan also introduced additional efforts to specifically target pricing.[84] Lastly, when asked to “provide the Committee with a report regarding how well military inventory is managed” in Canada compared to the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia, DND offered the following: As recently as 2015, the US Department of Defence has been cited in several audits regarding issues in the management of Defence inventories. These audits highlight issues with inventory management, materiel distribution, and asset visibility resulting in “high levels of inventory that were excess to requirements”. Combined with concerns regarding procurement and oversight of inventory management, a 2015 audit estimated that the US Department of Defence financial statements were overstated. Similar to DND/CAF, the US Department of Defence has instituted an inventory management improvement plan, formed new working groups and created guidance documents as methods to improve overall inventory management and accountability.[85] […] In the 2013–14 Audit report on the UK Ministry of Defence, the UK Auditor General states that challenges continue in material accountability. The Ministry of Defence must contend with aging and legacy warehousing inventory systems, areas of high stocktaking errors, inventory not on record, the need to adapt to ongoing changes, and challenges in pricing and valuation of inventory. The UK Auditor General qualified its opinion due to uncertainty in the accuracy of available information.[86] […] The 2015 Audits of the Financial Statements by the Australian National Audit Office found several areas specific to the military portfolio that had the potential to impact financial statements including “the management and valuation of inventory due to the materiality of the inventory balance at year end, the decentralized holdings and management by multiple parties, as well as the identification of and accounting for obsolete stock.”[87] In order to monitor DND’s progress in implementing its 2016 Action Plan, the therefore Committee recommends: RECOMMENDATION 2 That, by no later than 30 days after the end of each fiscal year beginning in 2017–2018, the Department of National Defence provide a one-page report to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts outlining the Department’s progress in implementing its 2016 Action Plan to properly record and value its inventory. This report should identify and provide the rationale for any delays in the implementation of the Action Plan’s proposed corrective measures. 4. Liabilities for Contaminated SitesIn 2014–2015, the AG recommended that the government “develop better processes to refine the accounting estimates and record the liabilities associated with contaminated sites at earlier stages of investigation.”[88] To address this recommendation, the government “developed a model to estimate liabilities for sites that are at an earlier stage of investigation. Using historical data for similar sites, the model is designed to predict how many sites that have no liability within a particular class will progress to remediation and what the projected remediation and monitoring costs could be for that class.”[89] The AG “found that the model used the data appropriately and performed its calculations accurately.”[90] Mr. Ferguson told the Committee that he is now satisfied that the government has made the necessary adjustments to its model and has achieved a better approach to estimating these liabilities.[91] It should be noted that the Committee commends the government for having successfully developed better processes to refine the accounting estimates and record the liabilities associated with contaminated sites at earlier stages of investigation. CONCLUSIONThe Committee would like to thank the Auditor General of Canada and his Office for their thorough audit, and congratulate the Government of Canada for receiving its 18th consecutive unmodified audit opinion, which attests that it properly reported its overall financial performance for 2015–2016 to Parliament and to Canadians. In this report the Committee made one recommendation that seeks to address the AG’s observation on the discount rates used for significant long-term liabilities, and one recommendation that seeks to address the AG’s observation on DND’s inventory management. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDED ACTIONS AND ASSOCIATED DEADLINESTable 1 – Summary of Recommended Actions and Associated Deadlines

[1] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2016. [2] Ibid. [3] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 31, 3 November 2016, 1530. [4] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 35, 24 November 2016, 1530. [6] Ibid. [7] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 31, 3 November 2016, 1530. [8] Ibid., 1535. [10] Ibid. [11] Ibid. [12] Ibid. [13] Ibid., p. 1.8. [14] Ibid., p. 1.4. [15] Ibid., p. 1.5. [16] Ibid. [17] Ibid., p. 1.7. [18] Ibid. [19] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 31, 3 November 2016, 1545. [20] Ibid., 1610. [21] Ibid., 1610. [22] Ibid., 1615. [23] Ibid., 1545 and 1550. [24] Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Frozen Allotments in Voted Authorities for Supplementary estimates (C), 2015-16. [25] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 31, 3 November 2016, 1550. [26] Ibid. [28] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 31, 3 November 2016, 1555. [29] Ibid. [30] Ibid., 1630. [31] Ibid. [32] Ibid., 1635. [33] Ibid., 1650. [34] Ibid. [35] Government of Canada, Budget 2017, Annex 2 – Debt Management Strategy for 2017-18. [36] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 31, 3 November 2016, 1700. [37] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2016, Volume III, p. 2.10. [38] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 31, 3 November 2016, 1710. [39] Ibid. [40] Ibid. [41] Ibid., 1725. [42] Ibid. [43] Status of Women Canada, Gender-Based Analysis Plus (GBA+) [44] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 31, 3 November 2016, 1725. [46] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 31, 3 November 2016, 1530. [47] Ibid., 1540. [48] Ibid. [50] Ibid., p. 2.42. [51] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 31, 3 November 2016, 1535. [53] Ibid. [54] Ibid. [55] Ibid. [56] Ibid. [57] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 31, 3 November 2016, 1610. [58] Ibid., 1605. [60] Ibid. [61] Ibid. [62] Ibid. [63] Ibid. [64] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 31, 3 November 2016, 1535. [65] Ibid. [67] Ibid. [68] Ibid. [69] Ibid. [70] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 31, 3 November 2016, 1535. [71] Ibid., 1615. [72] Ibid. [73] Ibid., 1620. [74] Ibid., 1640. [75] Ibid. [76] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 35, 24 November 2016, 1530. [77] Ibid., 1530 and 1535. [78] Report of the Department of National Defence received by email on 31 January 2017, p. 6. [79] Ibid. [80] Ibid. [81] Ibid., p. 7. [82] Ibid. [83] Ibid., p. 8. [84] Ibid. [85] Ibid., p. 10. [86] Ibid., p. 11. [87] Ibid. [89] Ibid. [90] Ibid. [91] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 31, 3 November 2016, 1535. |