PACP Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS OF CANADA 2017INTRODUCTIONA. The Public Accounts of CanadaThe Public Accounts of Canada are produced in three volumes:

The Public Accounts of Canada 2017, which pertains to the 2016–2017 fiscal year, were tabled in the House of Commons on 5 October 2017.[2] The House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts (the Committee) held a hearing on the Public Accounts of Canada 2017 on 17 October 2017.[3] From the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG or the Office), the Committee met with Michael Ferguson, Auditor General of Canada, and Karen Hogan, Principal. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) was represented by Bill Matthews, Comptroller General of Canada, and Diane Peressini, Executive Director, Government Accounting Policy and Reporting. Finally, Paul Rochon, Deputy Minister, and Nicholas Leswick, Assistant Deputy Minister, Economic and Fiscal Policy Branch, appeared on behalf of the Department of Finance Canada.[4] B. The Government of Canada’s ResponsibilityThe Government of Canada is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of its consolidated financial statements in accordance with its stated accounting policies—based on Canadian public sector accounting standards—“and for such internal control as the Government determines is necessary to enable the preparation of consolidated financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error.”[5] C. The Auditor General of Canada’s ResponsibilityThe Auditor General of Canada’s (AG) responsibility is to express an opinion on the government’s consolidated financial statements, based on his or her audit, conducted in accordance with the Canadian generally accepted auditing standards. These standards require that the AG “comply with ethical requirements and plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the consolidated financial statements of the government are free from material misstatement.”[6] Michael Ferguson, Auditor General of Canada, OAG, stressed that the consolidated statements “are a key government accountability document that can help parliamentarians understand the results of the government's financial transactions,” and that not many “national governments receive an unmodified audit opinion that its financial statements conform to an independently established set of accounting standards, but the Government of Canada has accomplished that for 19 years in a row.”[7] FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE AND FINANCIAL POSITIONThe Public Accounts of Canada 2017 outline the government’s financial performance during the 2016–2017 fiscal year and its financial position as of 31 March 2017.[8] Some financial highlights include:

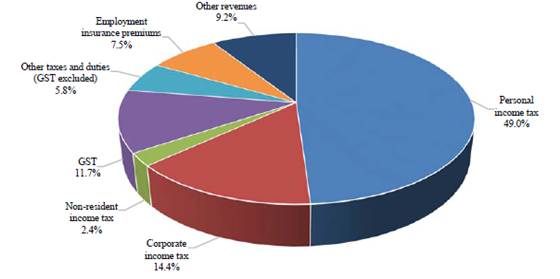

COMPOSITIONS OF REVENUES AND EXPENSES FOR 2016-2017Information about the composition of revenues and expenses for fiscal year 2016-2017 are presented below in Figures 1 and 2, respectively: Figure 1 – Composition of Revenues for 2016–2017

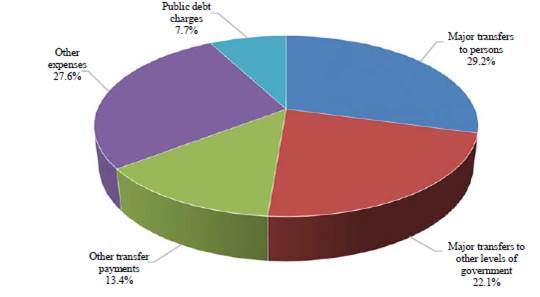

Source: Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2017, Volume I, p. 1.6. Figure 2 – Composition of Expenses for 2016–2017

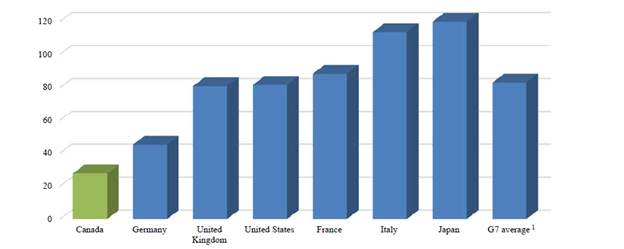

Source: Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2017, Volume I, p. 1.8. VARIOUS SUBJECTS STUDIED BY THE COMMITTEEA. Lapsed Funding and Frozen AllotmentsBill Matthews, Comptroller General of Canada, TBS, explained that lapsed funding “means how much money Parliament voted versus what the department actually spent,” and that there “is always going to be some amount of lapse. There are some departments that are chronically higher lapsers than others because of the nature of their business.”[15] In response to specific questions about lapsed funding for the Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED) portfolio, Mr. Matthews provided the following: When you look at ISED, the Canadian Space Agency was highlighted. Their lapse is very much related to one big project, the radar satellite projects, and when you're dealing with a complex project like satellite development, delays are not unimaginable. So you got delays there which cause a lapse. That's not ideal, but it's explainable.[16] He also provided an explanation about lapses in general and what becomes of unused funding: […] the other organizations you mentioned where you have lapses in grants and contributions dollars. The government has takers; you need to have applicants. Sometimes the applicants materialize in volumes we expect and sometimes they don't. Then you have an issue of whether you can negotiate a transfer payment agreement or not. Depending on the nature of the department, you may see some delays. Infrastructure is a great example of where negotiations cause delays. In terms of the ability to carry forward money, there's a built-in carry forward around operating and capital. Departments are allowed to carry forward 5% of operating and a certain percentage of capital. There is no automatic rollover of grants and contributions dollars. If a department can't spend its grants and contributions dollars, they have to make an application to our friends in the Department of Finance and say they would like to spend this money next year. If Finance blesses it, it then would get picked up again in the supply cycle, back to Parliament to get voted, and away we go again.[17] Mr. Matthews, furthermore, provided the following explanation of frozen allotments: Sometimes partway through the year something happens where a department knows it can't spend the money. A decision is made and the department is told not to spend the money. It might be a budget cut, like one placed on travel, which was one we put in place a couple of years ago, and also one on professional services. We freeze money. When you see a frozen allotment, if you're trying to understand what happened with the department, it's important to ask how much of it was planned versus how much of it was frozen or not frozen. It is to give you a sense of whether it is really just program money that wasn't spent or whether there was something else going on there, so in fact, it was actually a planned lapsed. That's why we have now disclosed these frozen allotments for you here. That is new information that has been available in volume II for two years now in the frozen allotments, which gives members a better sense of what's really at play, in terms of departmental spending and the results that they achieve.[18] According to the Government of Canada, for 2016–2017, “the total amount frozen in voted authorities is $2,958,440,536 as of January 10, 2017. Most of these frozen allotments are due to the planned reprofiling of funds ($2,119,910,423) to future years, and uncommitted authorities in the Treasury Board managed central votes ($579,378,780).”[19] B. Composition of Canada’s Government DebtAs shown in Figure 3, and as stated in the Public Accounts of Canada 2017, “Canada’s total government net debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 27.6 [%] in 2016, according to the IMF [International Monterary Fund]. This is the lowest level among G7 countries, which the IMF estimates will record an average net debt of 83.0 [%] of GDP in that same year.”[20] Specifically, the net debt for the 2016-2017 fiscal year was $714 billion[21] and its composition was explained by Mr. Matthews as follows: The net debt is very much around liabilities less financial assets. That's the cash and things we can turn into cash, accounts receivable, for instance. That's what gets you to net debt. It is your liabilities less your financial assets, and the net debt is $714 billion.[22] Figure 3 – G7 Total Government Net Debt-to-GDP, 2016

Source: Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2017, Volume I, p. 1.21. When questioned about the IMF methodology to calculate this value and compare various countries, Michael Ferguson provided the following: To me, the IMF calculation of net debt to GDP is a good measure from a relative point of view, but not from an absolute point of view. Relatively, the measure is very good because it shows how Canada compares on a relative basis, in apples-to-apples comparisons to other countries. It essentially shows that the next best country in the G7 has a debt burden that is roughly twice Canada's—and I believe that's Germany—and then after that I believe it's the U.K. and the U.S. that are four times that of Canada. On a relative basis, it's a good measure.[23] However, he also provided the following opinon: I'm not so fond of the percentage comparison, though, because it takes the federal government's net debt and, as I understand it, deducts the federal government's pension liabilities. The $240 billion that the federal government owes in pension liabilities to its employees, I believe, is deducted. It adds in the net debt of the provinces and of the local governments, so it expands net debt to not just a Government of Canada definition but to a definition of all net debt of all governments in Canada. Then it deducts the assets of the Canada pension plan and the Quebec pension plan. Again, it goes through all of that to try to put things on a comparative basis to other countries, because not all countries record their pension liability. One reason Canada can get 19 years' worth of clean audit opinions is that Canada records its pension liabilities, while other countries don't. . . . In my opinion, the best measure of debt to GDP—in terms of the federal government itself—is the net debt-to-GDP measure, which is the $714 billion of net debt in relation to the GDP of Canada, which is probably just slightly over $2 trillion. I believe that comes out to somewhere around 35%, and I think that is the best measure.[24] C. Accuracy of Deficit ProjectionsIn response to questions about the accuracy, or “honesty,” of deficit projections in the federal budget—which are sometimes much higher than the actual deficit reported in the Public Accoutns—Mr. Matthews provided the following: The forecasting ability has improved over the years. The economy does change, and I'll leave it to my colleagues from Finance to explain what has happened on the economic side. If the theory is that there's deliberate pessimism in the forecast—there is a bit of that—for risk, Finance will speak to that, but is there any systematic deliberate under-forecasting? No, there's not. It is challenging, based on all the economic results and what's happening globally today.[25] Moreover, Paul Rochon, Deputy Minister, Finance Canada, provided this additional explanation: I would add that if you're comparing the $29 billion to the $17 billion, it's roughly a $12‑billion difference. There is $6 billion of that which actually relates to a contingency reserve that was included in the $29 billion. That was a forecast that was done in March 2016, at a time when the economy was weak. Oil prices were around $25, if I go from memory. Of course, the economy recovered quite nicely, and has recovered quite nicely, so the combination of not needing that amount of contingency, plus a stronger economy as things evolved, meant that the overall deficit came in much lower than projected.[26] D. Debt Management StrategyIn response to a specific question about why the government’s interest expense for 2016-2017 was lower than projected in the budget, Paul Rochon explained “that the 10‑year government bond rate came in about 30 basis points lower than [the Department] had projected at the time of the budget.”[27] More generally, Bill Matthews cited the “debt management strategy document, a Department of Finance publication” and added that it is “an extremely useful document in terms of understanding the debt management strategy of the federal government.”[28] That is, the Debt Management Strategy “sets out the Government of Canada’s objectives, strategy and borrowing plans for its domestic debt program and the management of its official international reserves. Borrowing activities support the ongoing refinancing of government debt coming to maturity, the execution of the budget plan and the financial operations of the Government.”[29] E. Debts, Obligations and Claims Written Off or ForgivenWhen asked to provide examples of write-offs and what types of elements would constitute the majority of the $4.3 billion that the federal government either wrote-off or forgave in fiscal year 2016-2017,[30] Bill Matthews provided the following: It is indeed in volume III, section 2, where there are all sorts of disclosures, department by department, on the amounts written off or forgiven. The ones that will jump out at you if you're looking to that section are related to child and family services and the revenue agency. Here, you're looking at programs like the Canada student loans program and taxes and those types of things. It's very much tied to the nature of the program, where the government has determined that either they cannot collect or they have basically written off the debt.[31] He also added the following: [In] preparing the Public Accounts of Canada, as accountants we have to assess how much money we will receive from individuals and organizations. If we think that we will not receive certain amounts, we can make adjustments to the Public Accounts. That's all background accounting that we would do. If the loan is worth $100 and we think they are going to pay only $90, we can do an adjustment—and the Auditor General would actually require us to—that says, “Here is our best estimate of what we are going to collect.” That is separate from the process of writeoff, forgiveness, or remission. To do that, with some exceptions, one has to come to the Treasury Board and formally get an approval. It's good housekeeping, and it does get publicly disclosed. That's why it is important to do. If you are in the business of issuing student loans, or if you are in the business of supporting some vulnerable Canadians and thinking about loans for immigration, you're going to lose some money. We do encourage departments, if they think they can't collect this, to come on in, when the time is right, and write it off. On the one hand, it's a big dollar amount; on the other hand, we do want departments to do good housekeeping and get this stuff done.[32] Additionally, when questioned about what new practices are being followed by departments to improve due diligence regarding the collection of debts before they are written off, Bill Matthews spoke about a few related pilot projects currently in place: They were successful. When you are looking at these pilots.... I am not convinced it would be successful in every case, but if you look at debt related to pension overpayments and those types of things, where you have a relationship with the organization or the person, absolutely. If it's a one-off, where you've dealt with the organization only one time, the receiver general would probably struggle just as a private company would. We've had some good success, and we are going to continue the pilot. It's going to be extended. … As a result of the pilot, we will be issuing guidance—it won't be “musts”—to departments: if it's this kind of debt, the receiver general works best; if it's this kind of debt, CRA is better; if it's this kind of debt, do something different.[33] THE AUDITOR GENERAL OF CANADA’S OPINION AND OBSERVATIONS ON THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS OF CANADA 2017A. Auditor General of Canada’s OpinionFor a 19th consecutive year, the AG expressed an unmodified audit opinion on the government’s consolidated financial statements (as presented in the Public Accounts of Canada 2017).[34] Bill Matthews also acknowledged “the excellent work of the financial community across the Government of Canada in realizing these results,” and added that per a recent OECD report, “Canada's fiscal reporting framework employs many best practices, with a notable feature being Canada's use of websites, and in particular the Treasury Board Secretariat's InfoBase, to give access to a wide set of information.”[35] B. Auditor General of Canada’s ObservationsRegarding the audit of the federal government’s consolidated financial statements, the AG sometimes makes observations on matters that the Office would like to bring to Parliament’s attention. For the fiscal year ended 31 March 2017, the AG made three observations on the following subjects: the transformation of pay administration (including matters pertaining to the Phoenix system); the discount rates selected by management; and, the Department of National Defence’s inventory.[36] (i) Transformation of Pay AdministrationAccording to the AG, “pay and benefits represent one of the Government of Canada’s largest expenses. To transform the way it administers pay, the Government consolidated many of its pay services in Miramichi, New Brunswick, and implemented Phoenix, a new pay system, for approximately 290,000 Public Service employees. The new system was fully implemented by the end of April 2016 and processed approximately $22 billion in pay expenses in 2016–2017.”[37] Further to the AG’s work pertaining to the audit opinion, the Office determined that it could not rely upon the pay system’s internal controls to ensure it could process and record pay accurately.[38] The AG added the following: For example, an information technology system must have strong controls over who is granted access, who can change data and what changes they can make. These controls are particularly important in situations where there is a large number of people accessing the system, as is the case for Phoenix. Also, key tasks need to be done by different people; otherwise, improper pay transactions could be created, or people could have unauthorized access to the private information of other employees. The Government was not able to adequately explain to [the Office] what tasks certain users were able to do in Phoenix.[39] The AG further stated that in order to mitigate the challenges pertaining to the system’s internal controls, the Office increased its sample size for its study.[40] Some of the audit results are as follows:

In spite of these challenges, the AG was still able to determine the financial statements of the Government of Canada are presented accurately and fairly; this is because the overpayments and underpayments were able to mostly offset one another.[45] The AG also stated the following: The extent of the errors we found and the time it takes to make corrections are unacceptable, given the direct impact on employees. Resolving pay issues is a shared responsibility across the Government. While Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) is responsible for processing payroll transactions, departments also play an important role in providing timely and accurate information to PSPC about changes to employee pay.[46] The AG further found that the “extent of the errors that affected individuals and the time it takes to correct errors in pay are unacceptable” and reported that the Office is conducting two performance audits of the government's initiative to transform pay administration, the first of which is planned to be presented to Parliament in November 2017.[47] Despite the Committee's responsibility to focus on the accounting aspects of this report and the fact that the overpayments and underpayments disbursed to employees, worth $20 million each, offset each other, the Committee would like to emphasize that these errors can have significant impacts on the lives of public servants. Nothwithstanding the progress that has been made to address the challenges of this new pay administration system, or any current related investigations, studies or preformance audits, the Committee recommends: RECOMMENDATION 1 – Pertaining to the Pay Administration System That, within 120 days of the tabling of this report, the Government of Canada present a report to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts detailing what progress has been made with regard to improving the internal controls pertaining to the pay administration system. (ii) Discount Rates Selected by ManagementAs the AG reported in the Public Accounts of Canada 2017, the “Government of Canada has an ongoing project to update the way it determines the discount rates used in its estimates of long-term liabilities. The reasonableness of these estimates has a direct impact on the financial information included in the consolidated financial statements and used by Parliament and Canadians for decision making. While the Government has analysed options, it has not yet concluded on how it will change its method to determine discount rates.”[48] Moreover, the AG explained that it is important that the federal government’s process for determining discount rates be sound and supported by observable and relevant data.[49] And although the Office has “concluded that the assumptions underlying the Government’s significant estimates are within a reasonable range, historically, certain discount rates have been at the high end of the acceptable range when compared with market trends. Using a higher discount rate yields a lower estimate for long-term liabilities.”[50] Given the impact that these estimates can have on the government’s consolidated financial statements, the AG would expect “the Government to complete its project and change the way it determines discount rates in fiscal year 2017–2018,” and recommends that that, within the requirements of the Canadian Public Sector Accounting Standards, it consider industry practices in both the public and private sectors, emerging changes in standards, and trends in the Canadian financial market. Going forward, the Government should periodically validate its estimates by comparing with actual experience and adjust the methods as needed.”[51] When questioned about this matter, the AG’s response was as follows: I think when it comes to selecting discount rates for things like the unfunded portion of the pension plan, that's where there may be some differences between what the federal government is using to select a discount rate and what other governments would use. One of the parts of the analysis that needs to be done on the discount rates is looking at that comparison to others and also looking to make sure there's consistency between the different liabilities that the federal government has and how they're selecting discount rates for those various liabilities. There are some places where the way the federal government is selecting the discount rates may be unique to the federal government, but all of that needs to be part of the analysis that we've recommended they do to rationalize the discount rates they're using.[52] Furthermore, Paul Rochon added the following: To the extent that interest rates rise, naturally the debt charges on our market debt will increase. There will be an offset, however, from the actuarial value of the pension obligations, because as the discount rate on those obligations rises, the current service costs will be reduced, but I would expect on net, the answer to your question is that, generally speaking, with an increase in interest rates, debt charges will increase.[53] Therefore, the Committee recommends: RECOMMENDATION 2 – Pertaining to the Discount Rates Used in Estimates of Long-term Liabilities That, within 120 days of the tabling of this report, pertaining to the way the Government of Canada determines discount rates used in estimates of long-term liabilities, the Comptroller General of Canada, the Receiver General for Canada, and the Department of Finance Canada present a joint report to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts outlining what progress has been made with regard to A) updating the way it determines discount rates; B) considering industry practices in both the public and private sectors, emerging changes in standards, and trends in the Canadian financial market; and C) periodically validating its estimates by comparing them with actual experience. (iii) Department of National Defence’s InventoryThe Department of National Defence’s (DND) inventory is important to the consolidated financial statements because, as of March 2017, it was valued at $5.8 billion and represents 85% of the government’s total inventory.[54] The AG “first reported on National Defence’s challenges to properly record and value inventory 14 years ago, and the problems have persisted. However, in the last few years, [the OAG] has seen improvement.”[55] The AG reported that in the 2016–2017 fiscal year, DND tabled a long-term action plan to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, and finds that National Defence appears to be on track to complete the action plan it presented to [the Committee]. The Department has made significant progress on better knowing the quantity of its inventory in its major depots, but it needs to improve the way it counts inventory at other locations. Considerable effort is still required as the Department also has to improve its pricing of inventory, its recognition of obsolete inventory, and its classification of items as either inventory or [Asset Pooled items].[56] Furthermore, Karen Hogan, Principal, Office of the Auditor General of Canada, added the following: We did see some progress this year, as we have seen over the last four years, at [DND]. This year, they did take on a large project, looking at the pricing of ammunition, so we definitely saw reduced errors in the pricing of ammunition. Where we continue to see work needed is in the area of obsolescence and in the area of valuation for consumables. They have two types of inventory, ammunition and non-ammunition, so it's all the non-ammunition that they now need to tackle a little better. We mentioned that last year they implemented an allowance, which accounted for some of the obsolescence, but again, that fixed the statements; it doesn't fix the underlying records. Some of the steps they have in their action plan this coming year are to look at some of those things.[57] COMMITTEE SUGGESTIONIn the three volumes of the Public Accounts of Canada, federal organizations are generally presented alphabetically; however, this can make it difficult to compare and study versions in both of Canada’s official languages (together). Therefore, in order to make it easier to compare both official language versions of the Public Accounts of Canada, the Committee recommends: RECOMMENDATION 3 – Pertaining to the Presentation of the Public Accounts of Canada That, within 120 days of the tabling of this report, the Receiver General for Canada consider implementing a way in which to include cross-reference information about federal organizations listed in the Public Accounts of Canada to account for the difference in pagination in versions presented in each of Canada’s two official languages; and, that said pagination be simplified (e.g., p. 1, 2, 3, … and not 1.2, 1.21, 1.3, etc.) CONCLUSIONThe Committee would like to thank the Auditor General of Canada and his Office for their thorough audit, and congratulate the Government of Canada for receiving its 19th consecutive unmodified audit opinion, which attests that it properly reported its overall financial performance for 2016-2017 to Parliament and to Canadians. In this report, the Committee has made two recommendations that aim to improve internal system controls for pay administration and the way the Government determines discount rates for use in fiscal reporting, and one recommendation to make it easier to compare and study the Public Accounts of Canada in both official language versions. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDED ACTIONS AND ASSOCIATED DEADLINESTable 1 – Summary of Recommended Actions and Associated Deadlines

[1] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2017. [2] Ibid. [3] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 71, 17 October 2017. [4] Ibid. [5] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2017, Volume I, p. 2.4. [6] Ibid. [7] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 71, 17 October 2017, 0845. [8] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2017, About the Public Accounts of Canada. [10] Ibid. [11] Ibid. [12] Ibid. [13] Ibid., p. 1.8. [14] Ibid., p. 1.5. [15] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 71, 17 October 2017, 0905. [16] Ibid., 0945. [17] Ibid. [18] Ibid., 0905. [19] Government of Canada, Frozen Allotments in Voted Authorities for Supplementary estimates (C), 2016-17. [20] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2017, Volume I, p. 1.21. [21] Ibid., p. 1.13. [22] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 71, 17 October 2017, 0920. [23] Ibid., 0950. [24] Ibid. [25] Ibid., 1010. [26] Ibid., 1015. [27] Ibid., 1000. [28] Ibid. [29] Government of Canada, Budget 2017, Annex 2 – Debt Management Strategy for 2017-18. [30] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2017, Volume III, p. 2.11. [31] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 71, 17 October 2017, 0925. [32] Ibid., 0930. [33] Ibid., 0935. [34] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2016, Volume I, p. 2.42. [35] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 71, 17 October 2017, 0855. For further information, please refer to Rationalising Government Fiscal Reporting: Lessons Learned from Australia, Canada, France and the United Kingdom on how to Better Address Users’ Needs, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, May 2017. (Currently only available in English.) [36] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2016, Volume I, pp. 2.42-2.44. [37] Ibid., p. 2.42. [38] Ibid. [39] Ibid. [40] Ibid. [41] Ibid. [42] Ibid. [43] Ibid. [44] Ibid. [45] Ibid. [46] Ibid. [47] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 71, 17 October 2017, 0850. [48] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2016, Volume I, p. 2.43. [49] Ibid. [50] Ibid. [51] Ibid. [52] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 71, 17 October 2017, 0950. [53] Ibid., 0920. [54] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2016, Volume I, p. 2.43. [55] Ibid. [56] Ibid., p. 2.44. [57] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Meeting 71, 17 October 2017, 0930. |