PACP Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

REPORT 3, ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE IN THE CANADIAN ARMED FORCES, OF THE 2018 SPRING REPORTS OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL OF CANADA

Introduction

According to the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG), the “purpose of the military justice system is to contribute to the Canadian Armed Forces’ effectiveness by maintaining discipline, efficiency, and morale,”[1] and applies to all regular force and primary reserve force members.[2] The system “is anchored in the National Defence Act, which includes the Code of Service Discipline, and the Queen’s Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Forces. Together, these describe various offences, as well as authorities, rules, and procedures.”[3]

Charges may be laid for military offences under the Code for military incidents (e.g., insubordination or absence without permission) as well as incidents in a civilian context (e.g., theft or sexual assault).[4] However, murder, manslaughter, or child abduction charges brought against a military member for an incident that happened in Canada are handled by the civilian justice system.[5]

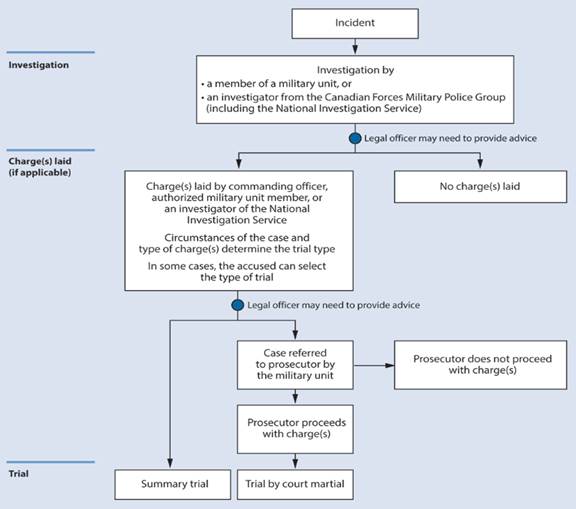

The OAG explains that the “military justice system has two levels [See Figure 1]. Charges can be dealt with through a summary trial or by court martial.

- Summary trials are intended to dispense prompt but fair justice for less serious offences. Summary trials are presided over by commanding officers or other authorized officers. Generally, the accused is not represented by legal counsel in a summary trial.

- A court martial is a formal trial presided over by a military judge. The accused has the right to be represented by legal counsel. A court martial follows many of the same rules that apply to criminal proceedings in civilian courts.”[6]

Additionally, the “circumstances of each case, including the nature of the charges and the rank of the accused, will determine whether the case will proceed by summary trial or by court martial. In some cases the accused can select the type of trial.”[7] Figure 1 provides information about the basic stages of the military justice system; Figure 2 provides information about the various roles and responsibilities within it.

Figure 1—Basic Stages of the Military Justice Process

Source: Office of the Auditor General of Canada, Administration of Justice in the Canadian Armed Forces, Report 3 of the 2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Exhibit 3.1.

Figure 2—Primary Roles and Responsibilities within the Military Justice System

Role |

Responsibility |

Commanding officers of military units |

Commanding officers are responsible for maintaining discipline among the members of the military units across the Canadian Armed Forces, including the Canadian Army, the Royal Canadian Air Force, and the Royal Canadian Navy. They have the authority to request and assign investigations, lay charges, preside over summary trials, and impose punishments. They can also delegate some of these authorities. |

Canadian Forces Military Police Group (Military Police) |

Under the authority of the Canadian Forces Provost Marshal, the Military Police has the authority to investigate alleged incidents. Part of this group, the National Investigation Service investigates serious and sensitive offences. Its investigators can lay charges. |

Office of the Judge Advocate General |

The Judge Advocate General is the legal adviser to the Governor General of Canada, the Minister of National Defence, and the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces on matters relating to military law. Despite the position title, the Judge Advocate General does not have judicial functions. The Judge Advocate General also has the superintendence of the administration of military justice in the Canadian Armed Forces. As such, the Office of the Judge Advocate General is responsible for developing legislation, policies, and directives on military justice. It also provides legal advice to military units, and reviews and reports on the military justice system. |

Office of the Chief Military Judge (including the Court Martial Administrator) |

This office includes the Chief Military Judge and three other military judges. They preside over court martial cases. The Court Martial Administrator provides administrative support to the Chief Military Judge. |

Canadian Military Prosecution Service |

Under the authority of the Director of Military Prosecutions, this office determines whether to proceed with charges that would be tried by court martial, and it is responsible for the conduct of all court martial prosecutions. The Director of Military Prosecutions also counsels the Minister of National Defence in cases that are appealed. |

Defence Counsel Services |

Under the direction of the Director of Defence Counsel Services, this office provides legal advice and representation. |

Source: Office of the Auditor General of Canada, Administration of Justice in the Canadian Armed Forces, Report 3 of the 2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Exhibit 3.2.

In the Spring of 2018, the OAG released a performance audit whose purpose was to determine “whether the Canadian Armed Forces administered the military justice system efficiently,” and in particular, to assess “the effectiveness of the Canadian Armed Forces in processing military justice cases in a timely manner.”[8]

In the context of this audit, it should be noted that the “Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees every accused person the right to be tried within a reasonable time, and to retain and instruct defence counsel without delay. The Supreme Court of Canada recently emphasized that the prompt processing of charges is a fundamental principle.”[9]

On 22 October 2018, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts (the Committee) held a hearing on this audit. In attendance, from the OAG were Jerome Berthelette, Assistant Auditor General of Canada; Andrew Hayes, Senior General Counsel; and, Chantal Thibaudeau, Director. From the Department of National Defence (the Department) were Jody Thomas, Deputy Minister, and Commodore Geneviève Bernatchez, Judge Advocate General (JAG) of the Canadian Armed Forces.[10]

Findings and Recommendations

As reported by the AG to the Committee, the issue of inadequate data collection and use is a persistent problem facing federal organizations. Given the significance of sound data in the accurate delivery and assessment of program effectiveness, the Committee has made this issue one of its key and consistent priorities.

A. Resolving Military Justice Cases

The OAG found “delays throughout the various stages of the military justice process,” and “that the Canadian Armed Forces did not set time standards for some steps of the process.”[11] Moreover, “it often took too long to decide whether charges should be laid and to refer cases to prosecutors. Prosecutors did not meet their time standards for making decisions to proceed to court martial. Where they did proceed, it took too long to schedule the court martial.”[12]

Regarding summary trials, the OAG found the following:

- Per the “Judge Advocate General 2016-17 Annual Report, 553 summary trials were completed in that fiscal year. The Judge Advocate General reported that these cases took an average of three months to complete from the time of the offence, but that about 18% took more than six months. These summary trial cases mostly involved minor disciplinary charges.”[13]

- Of the 117 summary trial cases examined, 99 were investigated solely by the military units, a process which the OAG found took too long to lay charges. Also, on average, “the units completed the investigation within 1.5 weeks, but commanding officers took an additional 5 weeks, on average, to lay the charges;” summary trial files contained no justifications for these delays.[14]

- Military Police investigated the remaining 18 summary trial cases; 12 of the 18 cases took more than 30 days to investigate and did not include a written justification for the delay as required by internal policy.[15]

Overall, the OAG found delays with respect to investigations, laying charges, referring charges to a prosecutor, proceeding to courts martial, and setting the dates for courts martial.[16]

According to the OAG, “these delays prevented the Canadian Armed Forces from enforcing prompt and efficient discipline, and ensuring that justice was carried out in a timely manner.”[17] Perhaps more alarmingly, the OAG also found 10 examples outside of its sample of 20 completed cases in which “delays contributed to decisions to dismiss or not to proceed with charges.”[18]

Therefore, the OAG recommended that the “Canadian Armed Forces should review its military justice processes to identify the causes of delays and to implement corrective measures to reduce them.”[19]

In response to this recommendation, the Department stated in its Detailed Management Action Plan that it is developing a “military justice case management tool and database. This system, called the Justice Administration and Information Management System, or JAIMS, is being developed in the 2018-19 fiscal year,” and is expected to be fully operational by September 2019.[20]

According to the Department, “JAIMS will electronically track discipline files from the receipt of a complaint through to closure of the file. The system will allow military justice stakeholders to access real-time data on files as they progress through the military justice system and will prompt key actors when they are required to take action. It is expected that management of military justice system files with the JAIMS will significantly reduce delays. The JAIMS will also be integrated with a new military justice performance measurement system, expected to be launched concurrently.”[21] As such, JAIMS “will deliver measurable data on the performance of the military justice system, allowing for the identification of system weaknesses—including in the area of delay—and the development of targeted measures to address them.”[22]

When questioned about this issue, Jody Thomas, Deputy Minister, Department of National Defence, provided the following:

I think there are a number of elements. There is no one answer. I can't give you a simple answer as to why there are delays. Sometimes the victim doesn't want to come forward, or the people involved in the case are deployed. It's an operational organization where people are moving all of the time. Time delays within units have to do with being deployed on operations. Sometimes it has to do with training. Sometimes it has to do with the availability of judges or prosecutors. There are a number of factors.

I do believe, and I may be alone in this, that data will help Commodore Bernatchez manage the operation differently, because she will see.... She believes she has enough resources; perhaps she doesn't, and we will see a particular bottleneck in one part of the country or one part of the process or the way in which we execute certain parts of the process.[23]

Therefore, to help prevent delays in the Canadian military justice system, the Committee recommends

Recommendation 1—on identifying and addressing delays

That, by 30 April 2019, the Department of National Defence present the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report detailing the progress made in identifying the causes of delays in the military justice process and in implementing corrective measures to reduce them.

It should be noted that many of the commitments in the Department’s action plan revolve around the successful development, implementation, and use of JAIMS. However, some members of the Committee expressed concern that an electronic management system is only as good as the data that feeds it. Hence, given the importance it places on the proper collection and use of quality data, the Committee recommends

Recommendation 2—on the proper collection and use of data

That, by 30 April 2019, the Department of National Defence present the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report detailing what progress has been made regarding 1) the development and implementation of the Justice Administration and Information Management System; and, 2) the development and implementation of training and sound business practices pertaining to its use.

B. Systemic Issues in the Military Justice Process

The OAG found “systemic weaknesses in the process that contributed to delays in enforcing discipline and administering justice. For example, the Canadian Armed Forces had not defined time standards for every phase of the military justice system. Even when time standards were defined, unexplained delays still occurred.”[24] It also noted “that human resource practices did not support the development of specialized expertise in litigation.”[25]

Additionally, “commanding officers did not immediately inform Defence Counsel Services of the accused’s request for defence counsel. Further, prosecutors did not provide the accused with all relevant information for their defence as soon as was practical. As well, [the OAG] found that the processes used by the Military Police to inform military units, and by the Canadian Military Prosecution Service to inform the Military Police, were inefficient.”[26]

According to the OAG, “the National Defence Act and associated regulations impose a duty to act promptly, but this duty is not explained in concrete terms. Various reviews of the military justice system have recommended establishing time standards for various stages of the military justice process.”[27] And while some standards had been developed—for example, for the JAG, Military Police, and the Director of Military Prosecutions—the OAG found that some unexplained delays still occurred.[28]

Consequently, the OAG recommended that “Canadian Armed Forces should define and communicate time standards for every phase of the military justice process and ensure there is a process for tracking and enforcing them.”[29]

In response, the Department stated in its action plan that it will complete a review of various time requirements for each phase of the military justice system process; this will allow for the introduction of “time standards that would benefit the military justice process in a manner that respects rules of fairness and legal requirements” by January 2019.[30]

Additionally, the Department explained how its new performance management system—linked to the JAIMS—will provide data on compliance with time standards and could be “also be used to require decision makers at various stages to justify why they could not meet time standards, which will assist in identifying and resolving the causes of delays.”[31]

Lastly, Commodore Geneviève Bernatchez, Judge Advocate General of the Canadian Armed Forces, provided further details about the system and its development:

With the justice administration and information management system that we will put in place and that we're currently developing—it's at stage two of its development, and we're testing every single phase as we go through—that will allow not only me, but every single actor that has a role to play as a decision-maker in the military justice system to see in real time where a case is and whether the time standards that have been defined and included in this computer-based system have been respected. If not, why not? Because they will be required to enter into that system the reasons that time standards were not met.[32]

Therefore, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 3—on time standards for the military justice process

That, by 30 April 2019, the Department of National Defence present the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report detailing what progress has been made with regard to defining, implementing, and communicating time standards for every phase of the military justice process and ensuring there is a process for tracking and enforcing them.

C. Communication Between Military Police investigators and Other Parties

In military justice cases, to determine whether or not charges will be laid, “commanding officers and their legal advisers need to consider the evidence from the investigation. Military Police investigators are required to provide a summary of each investigation to the relevant military unit.”[33]

In the OAG’s sample of 18 summary trial cases that the Military Police investigated, additional delays stemmed from commanding officers or legal officers requesting additional information from the Military Police, prior to making their decisions; these delays ranged from weeks to 10 months.[34]

Moreover, the OAG noted that there “was no formal requirement for the Canadian Military Prosecution Service to communicate with the Military Police about whether charges were laid, or to provide feedback on the quality of the police investigations,” and that “this lack of communication limited the Military Police’s ability to update its database and to improve the quality of future investigations.”[35]

Thus, the OAG recommended that the “Canadian Armed Forces should establish formal communication processes to ensure that the Military Police, the Director of Military Prosecutions, the Judge Advocate General’s legal officers, and the military units receive the information that they need to carry out their duties and functions in a timely manner.”[36]

In its action plan, the Department agreed with this recommendation, and in addition to the implementation of the JAIMS, committed to the following:

- “New standards for the delivery of military police reports will be implemented by 31 March 2019.”[37]

- Participating in the Military Justice Round Table in Spring 2018, and semi‑annually thereafter.[38]

- “The Director of Military Prosecutions will provide additional legal support to the Canadian Forces Military Police Academy by summer 2019.”[39]

When questioned about this matter, Jody Thomas acknowledged that without comprehensive change, concerns pertaining to the timeliness of key elements of the military justice process will persist:

Obviously for us, the system will help provide information to us, but if the underlying human behaviour doesn't change and we don't prioritize investigations and we don't train commanding officers differently and ensure that they give this kind of work and their responsibilities in the system for discipline the attention it needs, nothing will change other than the [Judge Advocate General] will have better information about what's going wrong.

Therefore, there has to be a systemic view and investment in commanding officers and everybody who plays a part in this system to ensure that they understand their responsibilities. Certainly this audit is a first step in that. The [Judge Advocate General] has a role, the chief of the defence staff has a role, the department has a role, as do commanding officers across the system. It is critical that we change human behaviour in this process.[40]

Regarding the Military Justice Round Table, Commodore Bernatchez provided the following:

The military justice round table goes to the heart of the need for better communications between the military justice actors. It brings together representatives from the Court Martial Appeal Court, the courts martial, the Canadian Forces provost marshal, the director of military prosecutions, the director of defence counsel services of the division of military justice and me.

It's a table that brings together these actors to discuss issues of mutual concern and to look at potential solutions. Issues of mutual concern are delays. This is preoccupying the civilian criminal justice system just as it does us. We're very mindful of the independence of these actors as we proceed.

The first meeting was held in June of 2018. The next meeting will be held in January. We develop agendas and discussion points to go to the most urgent of things. The conversations so far are very collegial. We are very happy to be brought back together to have those discussions and to be able to find solutions together, in a collegial manner, moving forward.[41]

Although it is pleased to learn about these developments, the Committee nevertheless recommends

Recommendation 4—on formal communications processes

That, by 30 April 2019, the Department of National Defence present the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report detailing what progress has been made with regard to the implementation of formal communication processes to ensure that the Military Police, the Director of Military Prosecutions, the Judge Advocate General’s legal officers, and the military units receive the information they require in a timely manner.

D. Communication with Defence Counsel Services

The OAG found that in 14 of the 20 court martial cases that it examined, “commanding officers did not immediately inform the Director of Defence Counsel Services of the accused’s decision regarding representation. In 4 of these cases, more than 30 days passed before the Director of Defence Counsel Services was notified that an accused had requested counsel.”[42] Moreover, “any delays in informing Defence Counsel Services are unacceptable given the accused’s right to obtain legal advice and representation without delay.”[43]

Additionally, the Director of Military Prosecution’s policy on disclosure requires prosecutors to disclose evidence to the accused as soon as is deemed “practicable” to do so; however, this is not defined.[44]

Lastly, out of the 20 court martial cases examined, the OAG found “that in 19 cases prosecutors took an average of three months to disclose evidence to defence counsel, and over a year for the other case. In 13 of these 20 cases, [the OAG] found that prosecutors disclosed evidence to defence counsel only after the prosecutor had decided to proceed to court martial.”[45] This is not consistent with the requirement to disclose evidence as soon as is practical to do so.[46]

Hence, the OAG recommended that the “Canadian Armed Forces should define and communicate expectations for the timely disclosure of all relevant information to members charged with an offence.”[47]

In its action plan, National Defence agreed with the recommendation and stated that a review of the timelines pertaining to “the delivery of disclosure to those charged with an offence” will be completed by January 2019.[48] Additionally, the Department noted that the Director of Military Prosecutions had already instituted changes to expedite disclosure to defence counsel; for example, prior to a case being assigned, “the prosecutor’s supervisor will request disclosure from the appropriate investigative agency.”[49]

In addition to explanations of anticipated benefits of the JAIMS pertaining to these challenges, Commodore Bernatchez further explained to the Committee that the Director of Military Prosecutions had reviewed “all the policies that specified the timeliness of disclosure to the accused;” she also acknowledged the validity of these concerns as raised by the OAG.[50]

Given that it strongly subscribes to the principle that “justice delayed is justice denied,” the Committee thus recommends

Recommendation 5—on the timely delivery of disclosure

That, by 30 April 2019, the Department of National Defence present the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report detailing what progress has been made with regard to defining and communicating expectations for the timely disclosure of all relevant information to members charged with an offence.

E. Development of Military Litigation Expertise

The JAG has 134 legal officers providing services to the Canadian Armed Forces (Canada and abroad) regarding military law; it also allows legal officers to rotate through various military legal services to develop a range of expertise.[51]

A 2008 external review recommended that prosecutors stay in their positions for a minimum of 5 years (an increase from the average of 2.25 years); however, the OAG found that the length of prosecution experience of military prosecutors had not increased since 2008.[52] Additionally, the OAG determined that the Office’s “human resource practices put more emphasis on gaining general legal experience than on developing litigation expertise—that is, court experience for prosecutors or defence counsel.”[53]

In light of this situation, the OAG recommended that the “Judge Advocate General should ensure that its human resource practices support the development of litigation expertise necessary for prosecutors and defence counsel.”[54]

In response, the Department stated in its action plan that it aims to implement a new policy on postings by the spring of 2019.[55] In the interim, however, it has already begun implementing this recommendation; for example, in 2018, “most of the legal officers assigned to the Canadian Military Prosecution Service and Defence Counsel Services will remain in their positions (and not be posted elsewhere) to ensure organizational stability and further development of litigation expertise.”[56]

During the hearing, Commodore Bernatchez also added the following:

That will build the expertise, but you're absolutely correct. We need to look at the entire organism that is the office of the JAG and see where we need to balance in order to ensure that there is also the generalist approach, because the office of the JAG is responsible for providing legal advice in all areas of military law and we need to develop the knowledge of it.

What I've asked for the support of the Canadian Armed Forces to do, and we've started this fall, is an occupational analysis of legal officers to see where we need the training, how long the posting should be, and what types of experience the legal officers need, whether they are litigators or generalists within the office of the JAG.

It's quite a long process. It usually takes five years in order for it to be meaningful. After we have completed the occupational analysis, we will be able to determine how we adjust our personnel management practices to ensure that we yield the best results for our clients.[57]

The Department agreed with this recommendation and in its action plan committed to the implementation of a new policy “mandating 5 year minimum posting periods for legal officers in prosecution and defence counsel positions.”[58] Therefore, the Committee recommends

Recommendation 6—on human resources management

That, by 30 April 2019, the Department of National Defence present the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report detailing what progress has been made with regard to the new policy mandating five year postings within the Office of the Judge Advocate General to support the development of litigation expertise necessary for prosecutors and defence counsel.

F. Case Management Systems and Practices

According to the OAG, the Office of the JAG “did not have the information needed to oversee the military justice system”; furthermore, “various stakeholders, notably the Military Police, the Canadian Military Prosecution Service, Defence Counsel Services, and the Office of the Judge Advocate General, had their own case tracking systems that did not capture all the needed information.”[59]

Notably, “some military units had no system or process to track and monitor their military justice cases.”[60] And if they did, the information was often limited, and did not include data on all phases of the military justice process.[61]

Additionally, the OAG found that the Office of the JAG’s database was neither complete nor up to date, “as many military units did not provide timely reports on their summary trials.”[62] In fact, in 23% of the summary trial cases examined by the OAG, “the military units were late in sending information” to the Office.[63]

Therefore, the OAG recommended that the “Canadian Armed Forces should put in place a case management system that contains the information needed to monitor and manage the progress and completion of military justice cases.”[64]

In its action plan, the Department’s response to this recommendation was similar to other related recommendations of this audit; that is, the Office of the JAG is currently developing the JAIMS, which is expected to improve case management. Given that recommendation 2 of this report already pertains to the implementation of the JAIMS, the Committee will not make another recommendation regarding this matter.

G. Reviewing the Military Justice System

The OAG found that the Office of the JAG did not adequately address or implement the recommendations of past internal and external reviews of the military justice system.[65] Moreover, although the National Defence Act requires the Office to regularly review the administration of military justice, the OAG found that it has not done so;[66] specifically, it did not “review or study the summary trial processes in the last 10 years.”[67]

Consequently, the OAG recommended that “the Office of the Judge Advocate General and the Canadian Armed Forces should regularly assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the administration of the military justice system and correct any identified weaknesses.”[68]

In response to this recommendation, the Department again referred to the JAIMS and its ability to track and assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the military justice process.[69] Moreover, similar to the Deputy Minister’s testimony, Commodore Bernatchez noted that a new information management system is not enough to address this issue:

You're absolutely correct that a computer system cannot, in and of itself, solve everything. When we're talking about timeliness, when we're talking about the effectiveness of the system, there needs to be a complete cohesion of things coming together. The solutions we're looking at and are currently working on are the time standards and the litigation experience, as has been noted by the Auditor General, to ensure that our prosecutors and our defence counsel have the expertise required moving forward. That requires training as well from all actors in the military justice system.[70]

Although it supports the Department’s approach, given the JAIMS’s full implementation date of September 2019, the Committee believes that is too long a time frame to wait to begin to fully analyze the military justice system’s efficiency and effectiveness. Therefore, notwithstanding the ongoing efforts regarding the development and implementation of the JAIMS, the Committee recommends

Recommendation 7—on the ongoing monitoring of the military justice system

That, by 30 April 2019, the Department of National Defence present the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report detailing what progress has been made with regard to its efforts to regularly assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the administration of the military justice system and to correct any identified weaknesses.

H. Implementation of a Prosecution Policy

According to the OAG, the “decision about whether charges proceed to court martial is among the most important steps in the prosecution process. Those decisions involve a high degree of professional judgment, and poor decisions may undermine confidence in the military justice system. The risk is that charges may not go to trial that should have, or that charges go to trial that should not have. The prosecutor has to be independent and free of bias. Considerable care must be taken in each case to ensure fairness and consistency.”[71] Furthermore,

- “The Director of Military Prosecutions is legally responsible and accountable for ensuring that decisions to proceed to court martial are well founded, made by the right people in the Canadian Military Prosecution Service, and properly documented.”[72]

- “The Canadian Military Prosecution Service has a policy that governs how decisions are made about whether to proceed to court martial. The policy includes a process to assign cases to prosecutors, along with the authorities they are allowed to exercise. It also includes requirements for documenting certain decisions, including the reasons that support those decisions.”[73]

Yet, the OAG found that “the Canadian Military Prosecution Service did not develop clear and defined processes to ensure it could implement the policy.”[74]

Thus, the OAG recommended that the “Director of Military Prosecutions should ensure that the policies and processes for assigning cases to prosecutors, and for documenting decisions made in military justice cases, are well defined, communicated, and fully implemented by the members of the Canadian Military Prosecution Service.”[75]

In its action plan, the Department agreed with this recommendation and stated that the Director of Military Prosecutions

- “has already made changes to the instruments for the appointment of prosecutors clarifying the limits for the exercise of their prosecutorial powers;”

- “has also made changes to better document the assignment of files to prosecutors,” including “by whom the assignment was made, when the assignment took place, and who has final disposition authority in the matter;” and,

- “will undertake a detailed policy review to be completed by 1 September 2018 to ensure that the policies properly reflect the above-noted changes and that all key decisions taken on a file affecting the disposition of that file are properly documented and communicated.”[76]

Commodore Bernatchez also provided the following, in response to questions about these particular shortcomings and associated corrective measures:

The problem that was brought to the attention of the director of military prosecutions, and which is well founded, is that this was not done, or documented, in a strict and systematic way in each case.

The Director of Military Prosecutions reacted immediately to that comment, that observation. He issued directives last summer to make sure that each time a decision is made by one of the prosecutors in a case, it is recorded by the prosecutor assigned to the case.

I also want to draw to the committee’s attention the fact that the Director of Military Prosecutions also completely reviewed the entire group of policies that apply to his prosecutors to make sure that there was an immediate response to the comments and observations made by the Auditor General.[77]

Again, given the priority it places on the importance of proper data collection and use, the Committee therefore recommends

Recommendation 8—on assigning cases to prosecutors and documenting their decisions

That, by 30 April 2019, the Department of National Defence present the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report detailing what progress has been made with regard to ensuring that the policies and processes for assigning cases to prosecutors, and for documenting decisions made in military justice cases, are well defined, communicated, and fully implemented by the members of the Canadian Military Prosecution Service.

I. Ensuring Independence

According to the OAG, the “directors of military prosecutions and defence counsel services are appointed by the Minister of National Defence for a fixed period of time. While they work under the general supervision of the Judge Advocate General, this appointment process is intended to allow those directors to operate with a high degree of independence,”[78] to ensure the interests of both sides of the military legal system.

Given that the JAG allocates legal officers to both prosecution and defence services, the OAG concluded that this practice can affect the ability of both directorates to manage their functions efficiently and effectively.[79]

Lastly, the OAG found that the JAG did not establish a formal agreement with the directors of both services “to define how overall supervision can be exercised without compromising their ability to perform their functions independently” nor did it “assess whether current practices and processes affect the independence needed by both directors to carry out their distinct roles in the military justice system.”[80]

Hence, the OAG recommended that the “Judge Advocate General should assess whether its practices and processes affect the independence of the Director of Military Prosecutions and the Director of Defence Counsel Services, and whether any adjustments or mitigation measures should be established.”[81]

The Department agreed with this recommendation; additionally, in March 2018, it issued the “2018-2021 Office of the JAG Strategic Direction,” whose Mission Statement and Relevance Proposition states that the superintendence of military justice administration must be accomplished while respecting the independent roles of each statutory actor within it.[82]

In responding to questions about this independence, Commodore Bernatchez acknowledged its crucial importance, and provided the Committee with the following testimony:

In reality, independence and the perception of independence are crucial for a legitimate military justice system. We take this matter very seriously.

The independent role of both the director of military prosecutions and the director of defence counsel services is provided for in the National Defence Act. The reporting relationship, or the general supervision that is exercised by the judge advocate general, has been provided by Parliament to the judge advocate general vis-à-vis those two actors.

In practice, on a day-to-day basis, I am exceedingly mindful of the independence of these two actors. In my strategic policy direction for the next three years, I have issued an obligation for all members of the office of the judge advocate general to assist me in the superintendence of the military justice system, in full respect of the independence of these actors.

As we're speaking, we have also completed a complete policy review of all the JAG policies as they pertain to the director of military prosecutions and the director of defence counsel services. We did that in consultation with these two directors, and we found no issues related to independence as far as these policies were concerned. The next thing we are doing currently is to continue to consult with the two directors to see what better practice we could develop to ensure not only factual independence but also the very important perception of independence.

One of the practices I've put in place this year for the reporting period is that, for the first time ever, I told the director of defence counsel services and the director of military prosecutions that they are responsible for their own personnel evaluation. I will have absolutely no role to play in this. They will evaluate them and send them directly to the centre for the selection for promotion.[83]

The Committee strongly believes that the independence of the JAG and the two directorates is paramount, and must be maintained in both perception and practice. And although it takes note of both the progress and commitments made by the Office in this area, the Committee nevertheless recommends

Recommendation 9—on the independence of the Director of Military Prosecutions and Director of Defence Counsel Services

That, by 30 April 2019, the Department of National Defence present the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report assessing whether the practices and processes of the Office of the Judge Advocate General affect the independence of the Director of Military Prosecutions and the Director of Defence Counsel Services, and whether any adjustments or mitigation measures should be established in response.

Conclusion

The Committee finds that the Canadian Armed Forces did not administer the military justice system efficiently, as evidenced by delays throughout the processes for both summary trials and court martial cases. Furthermore, “systemic weaknesses, including the lack of time standards and poor communication, compromised the timely and efficient resolution of military justice cases.”[84] Lastly, the Office of the Judge Advocate General did not provide effective oversight of the military justice system nor did it have the information needed to do so.

To address these concerns, the Committee has made nine recommendations to the Department of National Defence to help improve Canada’s military justice system. The courageous women and men of the Canadian Armed Forces, who are prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice for Canada, most decidedly deserve it.

Summary of Recommended Actions and Associated Deadlines

Table 1—Summary of Recommended Actions and Associated Deadlines

Recommendation |

Recommended Action |

Deadline |

Recommendation 1 |

The Department of National Defence should present the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report detailing the progress made in identifying the causes of delays in the military justice process and in implementing corrective measures to reduce them. |

30 April 2019 |

Recommendation 2 |

The Department should present the Committee with a report detailing what progress has been made regarding 1) the development and implementation of the Justice Administration and Information Management System; and, 2) the development and implementation of training and sound business practices pertaining to its use. |

30 April 2019 |

Recommendation 3 |

The Department should present the Committee with a report detailing what progress has been made with regard to defining, implementing, and communicating time standards for every phase of the military justice process and ensuring there is a process for tracking and enforcing them. |

30 April 2019 |

Recommendation 4 |

The Department should present the Committee with a report detailing what progress has been made with regard to the implementation of formal communication processes to ensure that the Military Police, the Director of Military Prosecutions, the Judge Advocate General’s legal officers, and the military units receive the information they require in a timely manner. |

30 April 2019 |

Recommendation 5 |

The Department should present the Committee with a report detailing what progress has been made with regard to defining and communicating expectations for the timely disclosure of all relevant information to members charged with an offence. |

30 April 2019 |

Recommendation 6 |

The Department should present the Committee with a report detailing what progress has been made with regard to the new policy mandating five year postings within the Office of the Judge Advocate General to support the development of litigation expertise necessary for prosecutors and defence counsel. |

30 April 2019 |

Recommendation 7 |

The Department should present the Committee with a report detailing what progress has been made with regard to its efforts to regularly assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the administration of the military justice system and to correct any identified weaknesses. |

30 April 2019 |

Recommendation 8 |

The Department should present the Committee with a report detailing what progress has been made with regard to ensuring that the policies and processes for assigning cases to prosecutors, and for documenting decisions made in military justice cases, are well defined, communicated, and fully implemented by the members of the Canadian Military Prosecution Service. |

30 April 2019 |

Recommendation 9 |

The Department should present the Committee with a report assessing whether the practices and processes of the Office of the Judge Advocate General affect the independence of the Director of Military Prosecutions and the Director of Defence Counsel Services, and whether any adjustments or mitigation measures should be established in response. |

30 April 2019 |

[1] Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG), Administration of Justice in the Canadian Armed Forces, Report 3 of the 2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, para. 3.2.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., para. 3.3.

[4] Ibid., para. 3.4.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., para. 3.5.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., para. 3.7.

[9] Ibid., para. 3.12.

[10] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 October 2018, Meeting No. 113. The term “JAG” can refer to both the position of Judge Advocate General or the Office of the Judge Advocate General.

[11] OAG, Administration of Justice in the Canadian Armed Forces, Report 3 of the 2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, para. 3.41.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., para. 3.20.

[14] Ibid., para. 3.21.

[15] Ibid., para. 3.22.

[16] Ibid., paras. 3.24 and 3.25.

[17] Ibid., para. 3.26.

[18] Ibid., para. 3.29.

[19] Ibid., para. 3.31.

[20] Department of National Defence, Detailed Management Action Plan, p. 1.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 October 2018, Meeting No. 113, 1650.

[24] OAG, Administration of Justice in the Canadian Armed Forces, Report 3 of the 2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, para. 3.32.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid., para. 3.33.

[27] Ibid., para. 3.38.

[28] Ibid., para. 3.41.

[29] Ibid., para. 3.43.

[30] Department of National Defence, Detailed Management Action Plan, p. 2.

[31] Ibid.

[32] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 October 2018, Meeting No. 113, 1600.

[33] OAG, Administration of Justice in the Canadian Armed Forces, Report 3 of the 2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, para. 3.44.

[34] Ibid., para. 3.45.

[35] Ibid., para. 3.46.

[36] Ibid., para. 3.47.

[37] Department of National Defence, Detailed Management Action Plan, p. 3.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 October 2018, Meeting No. 113, 1615.

[41] Ibid., 1620.

[42] OAG, Administration of Justice in the Canadian Armed Forces, Report 3 of the 2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, para. 3.49.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid., para. 3.50.

[45] Ibid., para. 3.51.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid., para. 3.52.

[48] Department of National Defence, Detailed Management Action Plan, pp. 3-4.

[49] Ibid.

[50] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 October 2018, Meeting No. 113, 1545.

[51] OAG, Administration of Justice in the Canadian Armed Forces, Report 3 of the 2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, para. 3.53.

[52] Ibid., para. 3.54.

[53] Ibid., para. 3.55.

[54] Ibid., para. 3.57.

[55] Department of National Defence, Detailed Management Action Plan, p. 4.

[56] Ibid.

[57] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 October 2018, Meeting No. 113, 1700.

[58] Department of National Defence, Detailed Management Action Plan, p. 5.

[59] OAG, Administration of Justice in the Canadian Armed Forces, Report 3 of the 2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, para. 3.65.

[60] Ibid., para. 3.66.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Ibid., para. 3.67.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Ibid., para. 3.70.

[65] Ibid., paras. 3.71 and 3.72.

[66] Ibid., para. 3.73.

[67] Ibid., para. 3.75.

[68] Ibid., para. 3.76.

[69] Department of National Defence, Detailed Management Action Plan, p. 7.

[70] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 October 2018, Meeting No. 113, 1645.

[71] OAG, Administration of Justice in the Canadian Armed Forces, Report 3 of the 2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, para. 3.77.

[72] Ibid., para. 3.78.

[73] Ibid., para. 3.79.

[74] Ibid., para. 3.80.

[75] Ibid., para. 3.82.

[76] Department of National Defence, Detailed Management Action Plan, p. 8.

[77] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 October 2018, Meeting No. 113, 1545.

[78] OAG, Administration of Justice in the Canadian Armed Forces, Report 3 of the 2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, para. 3.83.

[79] Ibid., para. 3.84.

[80] Ibid., para. 3.85.

[81] Ibid., para. 3.86.

[82] Department of National Defence, Detailed Management Action Plan, p. 9. For further reference, consult the “2018-2021 Office of the JAG Strategic Direction.”

[83] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 October 2018, Meeting No. 113, 1705.

[84] OAG, Administration of Justice in the Canadian Armed Forces, Report 3 of the 2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, para. 3.87.