RNNR Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

RETHINKING CANADA’S ENERGY INFORMATION SYSTEM: COLLABORATIVE MODELS IN A DATA-DRIVEN ECONOMY

A. Introduction: The Value of Energy Data

Between 26 April and 12 June 2018, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Natural Resources (the committee) conducted a study on the current state and future of Canada’s national energy data. The committee heard from a wide range of experts about the benefits of, and gaps in, Canadian energy information systems, as well as best practices for managing energy data and analyses moving forward. The committee is pleased to present its final report, which includes the study findings and recommendations to the Government of Canada.

“ Data is a national resource that is no different from our natural resources like energy, water, minerals, metals, or timber. If developed appropriately, it has the potential to yield enormous value for all Canadians.”

Ian Nieboer, RS Energy Group

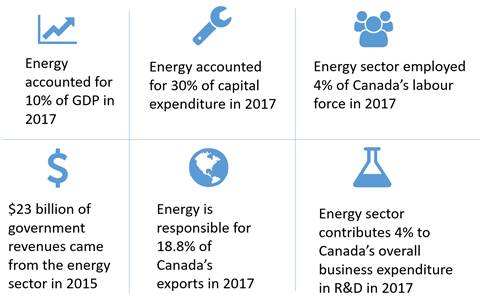

Canada needs accurate, timely and reliable energy data to support fact-based conversations, policies and business decisions regarding the energy sector and its impacts on the economy, society and environment. High-quality energy information can foster economic competitiveness by improving the understanding of the value proposition of energy resource development and associated social and environmental impacts, thereby facilitating investment decisions, enabling more expedient and environmentally-friendly projects, and strengthening public confidence in Canadian energy policy and decision making (Figure 1).[1]

Figure 1: The Contribution of Energy to the Canadian Economy

Source: Statistics Canada (as presented in a document submitted to RNNR).

Owing to the rapidly evolving nature of the energy sector, demand for Canadian energy data is constantly increasing. The advent and growth of new energy sources and technologies, coupled with Canada’s ongoing transition to a lower-carbon economy and greater public engagement in energy decision making are creating new demand for energy information.[2] In the words of Laura Oleson of Natural Resources Canada (NRCan):

As we look to the future, there are promising opportunities for energy data to be used in new ways to optimize industrial processes and reduce environmental impacts. Big data is enabling smart grids to improve efficiency and reduce the cost of electricity. Oil and gas companies are using AI-capable robots in oil exploration and production, which can increase productivity while reducing worker risk. Incorporating AI, big data analytics, and other information-based technologies into how we make, move, and use energy will be key for the continued competitiveness of Canada's energy industries....

In 2015, all the provinces and territories reached an agreement on a Canadian energy strategy that included goal 3.1: to “[i]mprove” the “quality of energy data across Canada.”[3] The aim of this report is to emphasize the importance of this national goal, and to offer further policy guidance to the Government of Canada, based on evidence from diverse experts from industry, civil society, academia, Indigenous organizations, the public sector and international agencies. The next section provides a brief assessment of Canada’s current energy information system, followed by a discussion of policy proposals and best practices for managing national energy data moving forward.

B. Canada’s Energy Information System(s)

Canada has a broad community of energy data users and collectors. Data users include policy makers and regulators at all levels of government; industry producers and private sector investors; academics; Indigenous governments and communities; non-governmental organizations; international partners and agencies; as well as individuals, both as consumers and citizens. Similarly, Canadian energy information is the collective product of different businesses, governments, research institutions, provincial and territorial utilities, and non-governmental organizations, among others.[4]

“People are becoming far more engaged in their energy lives and they want energy information.”

Monica Gattinger, University of Ottawa

In the federal government, most of the data related to Canadian energy is the product of the following four departments or agencies:

- Statistics Canada (StatsCan) collects, compiles and analyses information about industries and individuals in Canada, and has the legislative authority, under the Statistics Act, to acquire administrative data from any level of government, corporation or organization across the country. Much of StatsCan’s energy data is collected and disseminated by the department’s energy statistics program whose focus is on the production, transformation, distribution and consumption of energy. Other areas of StatsCan collect information pertaining to the energy sector, such as labour force statistics and information on energy science and technology.[5]

- Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) has a mandate under the Energy Efficiency Act to “provide energy use data to Canadians and to report to Parliament.” The department is also responsible for Canada’s monthly and annual submissions to the International Energy Agency (IEA), and publishes an annual Energy Fact Book, providing “key information on energy in Canada in a format that is accessible to non-experts.” NRCan works in collaboration with various partners, including StatsCan, provincial and territorial government regulators and utilities, industry and research institutions.[6]

- The National Energy Board’s (NEB) Departmental Results Framework includes the collection, monitoring, analysis and publication of energy information as part of the agency’s core responsibilities. While some data is collected by the NEB directly, more is sourced from federal and provincial agencies or, where necessary, third-party sources. The NEB uses energy data to create reports on various energy topics, including the agency’s short-term Market Snapshots and long-term annual energy outlooks, entitled Canada’s Energy Future.[7]

- Environment and Climate Change Canada’s (ECCC) national reports and inventories include information pertaining to the energy sector – such as Canada’s Inventory of Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks, the Air Pollutant Emissions Inventory and the Black Carbon Emissions Inventory. The department collects some of its own data – for example, through the Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program – and uses energy statistics and projections produced by StatsCan and the NEB. Where needed, ECCC also consults with provinces, territories and other third parties.[8]

The Government of Canada has an open data plan that aims to help guide developments in energy data and information-sharing policies. According to Pippa Feinstein of Lake Ontario Waterkeeper, the plan commits to “expanding and improving open data across federal public services with special attention paid to the extracted sector, federal science activities, and geospatial data.” In addition, Canada collaborates with international partners and agencies on information sharing initiatives pertaining to energy. A recent example is the North American Cooperation on Energy Information initiative, which, according to Ms. Oleson, has led to the creation of “the first ever shared map of North American energy supply infrastructure.”

“ Organization of [energy] information is important, otherwise we risk being a country that is data-rich

Greg Peterson, Statistics Canada

In its international recommendations for energy statistics, the United Nations Statistical Commission put forward best practices and principles regarding energy information, including: relevance and completeness, timeliness and punctuality, accuracy and reliability, coherence and comparability, accessibility and clarity, and political independence.[9] Witnesses generally agree that Canada’s energy information system could be improved according to these criteria. For example, the committee heard the following:

- Canada’s decentralized energy data, while abundant, can be difficult to navigate, interpret and verify, especially for non-experts.[10] Alan Fogwill of the Canadian Energy Research Institute (CERI) explained that generating a complete data set “requires a review of up to 20 sources of major and minor publications, [which is] beyond the resources and expertise of most stakeholders.” A survey conducted by CERI found that stakeholders have different levels of trust in producers of Canadian energy information: 67% trust in government agencies, 17% in governments, 50% in economic experts and academia, and 42% in industry associations (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Level of Stakeholder Trust in Different Producers of Energy Information in Canada

Source: Canadian Energy Research Institute (as presented in RNNR Evidence).

- Data measurement, definitions, policy tools and reporting standards vary among Canadian jurisdictions and information providers, leading to inconsistencies that limit the coherency and usability of some national data and can create confusion as to which sources are official or correct.[11] Out of 26 indicators assessed by CERI from various sources, 42% differed in value by more than 10%. Furthermore, according to Monica Gattinger of the University of Ottawa, “there are mountains of data in various organizations that aren't being transformed into information,” owing partly to gaps in data coordination and harmonization.

- Canadian energy data are generally reported 12 to 18 months after the end of the year; some are reported up to five years behind. These time lags are considered too long for a fast-paced economy with ever growing demand for real-time information.[12] Joy Romero of the Clean Resources Innovation Network explained that the lack of real-time data is particularly challenging for Canada’s innovation ecosystem, stating that Canada needs a data communications platform that is “searchable in real time, uses data analytics, and will connect all superclusters and innovators to a more fulsome picture of innovation in Canada.”

- Researchers are sometimes unable to access the source files of national energy analyses due to rules of proprietary and/or confidentiality.[13] According to the Canadian Academy of Engineering, some data models are proprietary to consulting companies and are accessible only to paying clients; others are proprietary to government agencies that are not mandated to provide access and support to all interested parties. Greg Peterson of StatsCan explained that the energy sector is dominated by a small number of large players, which “leads to issues of data suppression in order to protect the confidentiality of individual respondents.” Patrick Brown of Hydro Ottawa pointed out that matters of confidentiality arise, “first and foremost, when customer information is involved.”

- Some Canadian energy information is incomplete or lacking. A CERI study found that only 38% of the 189 potential energy indicators are

gathered in Canada. Examples of energy

topics that need better coverage include, among others:

- emerging technologies and new energy services, especially for biomass and new renewable energy sectors such as geothermal and solar photovoltaic;[14]

- oil and gas storage, refined production, interprovincial transfers, exports and transportation methods;[15]

- end-use energy consumption and conservation patterns, particularly for the electricity sector which generally lacks sector-specific economic data;[16]

- socioeconomic indicators – namely, information on low-income households facing energy poverty[17] and Indigenous women who, according to Myriam Landry of Quebec Native Women, “benefit the least from the economic impacts of [energy] projects and … will face the most direct negative impacts;” and

- energy and carbon flow in other economic sectors (e.g., forestry and agriculture).[18]

Given that most energy resource development falls under provincial jurisdiction, rethinking Canada’s energy information system has been an intergovernmental endeavor. According to Ms. Oleson, the federal government has been involved in ongoing discussions with the provinces and territories about how Canadian natural resources data can be improved more broadly, including larger questions about what data should be required by government. In that sense, she thinks reforms to Canada’s energy information system “would fit into a broader, all-encompassing national data strategy.” Furthermore, Mr. Peterson told the committee that StatsCan has embarked on a modernization initiative that is putting more emphasis on collaboration and partnerships, stating that Canada has to adopt “a more integrated approach to data, taking advantage of these new sources of information that are becoming available and finding mechanisms of putting them together.”

C. Towards a One-Stop Energy Shop for Canada

In-person and online consultations conducted by NRCan’s Generation Energy Council found that Canadians want “a one-stop shop where they can go for reliable and independent information” on energy in Canada. Furthermore, the Expert Panel on the Modernization of the National Energy Board envisions the creation of “a new, independent Canadian Energy Information Agency, separate from both policy and regulatory functions, accountable for providing decision-makers and the public with critical energy data, information, and analysis.”[19]

“Data systems that are good are focused, they collect only the data needed, they maximize the use of that data so that it's collected once and used often.”

Duncan Millard, International Energy Agency

Several witnesses support the idea of an independent energy information agency in Canada. The committee heard that, by working with existing data providers and energy stakeholders, such an agency should be mandated to collect, validate, analyse and distribute detailed regional and national energy information that is accurate, timely, transparent, comprehensive, user-friendly, internally-consistent, free of charge, responsive to the needs of different sectors, and independent of political influence. To this end, the proposed agency would aim to accomplish the following objectives:

- streamline data collection by establishing common definitions and reporting standards;

- ease the administrative burden on reporting organizations by collecting information only once and subsequently presenting it in the same place for the benefit of all;

- level the playing field among data users by making high-quality energy information accessible free of charge;

- establish safeguards to protect the sensitivity and/or confidentiality of energy data reported by the public, private companies and other organizations;

- provide authoritative energy reports and data analysis tools to facilitate evidence-based decision making and improve public energy literacy – including quarterly reports and forecast scenarios on energy supply, demand, sources, downstream consumption and trade, both interprovincially and internationally, as well as information that addresses the socioeconomic and environmental dimensions of Canadian energy (e.g., climate change impacts, cross-country data on energy poverty, and energy information specific to Indigenous peoples); and finally,

- assume an active role in energy decision making by advising government departments and agencies on energy matters upon request, and by making experts available to appear as witnesses in energy project hearings.[20]

The committee heard that the proposed energy information agency should work in partnership with existing federal government departments, namely StatsCan and NRCan, as well as Indigenous governments and communities, provincial and territorial governments, the private sector, and other relevant energy data groups and public interest organizations across Canada.[21] For example, Francis Bradley of the Canadian Electricity Association recommended that the agency consist of partnerships and information sharing agreements between the federal, provincial and territorial governments, “utilizing Statistics Canada for primary-source energy data or perhaps adopting this function itself.” Similarly, David Layzell of CESAR stated that the proposed agency needs to be closely linked to government departments that have the authority to collect energy data; “it needs a governance structure that engages the provinces, territories, municipalities, and industry associations that provide the data, as well as those organizations that are going to be users of that data.”

The committee also heard that a national energy information agency could be housed within existing federal organizations, namely StatsCan or the NEB.[22] Judith Dwarkin of RS Energy Group warned that setting up a new agency may be costly, stating that the NEB has “mounds of data, [and has] already taken the first step towards something that could look like a national energy database.” In considering whether or not to house an energy information provider within an existing federal organization or as a separate agency, government should take into account such factors including but not limited to: cost, political independence, ease of transition, pre-existing expertise and mandates, and the increased public trust enjoyed by independent agencies.

Witnesses identified several international models that could inspire reform in the Canadian energy information system – namely, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), Statistics Norway and the U.K. Committee on Climate Change.[23] According to John Conti of the EIA, most of his sophisticated clients extract 80% of their data needs from the EIA website on a weekly basis, which attests to the synergies and economies of scale of having one national energy agency. Pierre-Olivier Pineau of HEC Montreal pointed out that Norway, a major energy producer with a northern climate, would be a good source of inspiration for Canada. In addition to gathering statistics, the Norwegian equivalent of StatsCan conducts research and informs government, the investment community and the public on energy use, production and processing in Norway.

While reforming Canada’s energy information system is not a greenfield operation, the committee heard that it requires “substantial additional attention,” taking into account rapid evolutions in the energy sector, as well as the complex dynamics of data supply and demand in the digital age. According to Ms. Gattinger, reforms should be designed with long-term needs in mind and should aim to “maintain and leverage existing expertise and tailor Canada's system to the country's local circumstances.” She added that Canada’s focus needs to be on information, not just data: “Data is essential, but transforming data into information that's both relevant and accessible is crucial.”

[1] Standing Committee on Natural Resources (RNNR), Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament (Evidence): Greg Peterson (Director General, Agriculture, Energy, Environment and Transportation Statistics, Statistics Canada [StatsCan]); Laura Oleson (Director General, Energy Policy Branch, Energy Sector, Department of Natural Resources [NRCan]); Jim Keating (Executive Vice-President, Corporate Services and Offshore Development, Nalcor Energy); Timothy Egan (President and Chief Executive Officer, Canadian Gas Association); Judith Dwarkin (Chief Economist, RS Energy Group); Monica Gattinger (Professor, Chair of Positive Energy, Director of Institute for Science, Society and Policy, University of Ottawa); and Ian Nieboer (Director, RS Energy Group).

[2] RNNR Evidence: Peterson (StatsCan); Oleson (NRCan); Allan Fogwill (President and Chief Executive Officer, Canadian Energy Research Institute [CERI]); Patricia Lightburn (Manager, Science and Policy, David Suzuki Foundation); Pierre-Olivier Pineau (Professor, Energy Sector Management, HEC Montreal); Karine Péloffy (Managing Director, Quebec Environmental Law Centre); and Benjamin Israël (Analyst, Pembina Institute).

[4] RNNR Evidence: Oleson (NRCan); Gattinger (University of Ottawa); Peterson (StatsCan); Jim Fox (Vice-President, Integrated Energy Information and Analysis, National Energy Board [NEB]); Keating (Nalcor Energy); Egan (Canadian Gas Association); Francis Bradley (Chief Operating Officer, Canadian Electricity Association); and Dwarkin (RS Energy Group).

[7] Document submitted to RNNR by the NEB, entitled NEB Opening Statement.

[8] RNNR Evidence: Jacqueline Gonçalves (Director General, Science and Risk Assessment, Environment and Climate Change Canada [ECCC]) and Derek Hermanutz (Director General, Economic Analysis Directorate, Strategic Policy Branch, ECCC).

[10] RNNR Evidence: Bruce Cameron (Senior Advisor and Consultant, Quality Urban Energy Systems of Tomorrow [QUEST]); Kevin Birn (Director, Energy, IHS Markit); Keating (Nalcor Energy); Gonçalves (ECCC); Peterson (StatsCan); David Layzell (Professor and Director, Canadian Energy Systems Analysis Research [CESAR]); Ethan Zindler (Head of Americas, Bloomberg New Energy Finance [Bloomberg]); Fogwill (Canadian Energy Research Institute); Bruce Lourie (President, Ivey Foundation Toronto); Pineau (HEC Montreal); Kathleen Vaillancourt (President, ESMIA Consultants Inc., and Representative, Canadian Academy of Engineering); Bill Eggerston (Executive Director, Canadian Association for Renewable Energies); Israël (Pembina Institute); Gattinger (University of Ottawa); Maike Luiken (President, IEEE Canada); Fox (NEB); Oleson (NRCan); Layzell (CESAR); Greg Abbott (Vice-President, Market Operations, Intercontinental Exchange [ICE NGX]); Lightburn (David Suzuki Foundation); Nieboer (RS Energy Group); Joy Romero (Vice-President, Canadian Natural Resources Limited, and Chair, Clean Resource Innovation Network [CRIN]); and Dwarkin (RS Energy Group).

[11] Ibid.

[12] RNNR Evidence: Fogwill (CERI); Duncan Millard (Chief Statistician and Head of the Energy Data Centre, International Energy Agency [IEA]); Cameron (QUEST); Patrick DeRochie (Climate and Energy Program Manager, Environmental Defence); Israël (Pembina Institute); Lightburn (David Suzuki Foundation); Romero (CRIN); Donald Mustard (Researcher); and Dwarkin (RS Energy Group).

[13] RNNR Evidence: Pippa Feinstein (Counsel, Lake Ontario Waterkeeper); Bradford Griffin (Canadian Energy and Emissions Data Centre [CEEDC]); Romero (CRIN); Vaillancourt (Canadian Academy of Engineering); Péloffy (Quebec Environmental Law Centre); Cameron (QUEST); Lourie (Ivey Foundation); and the Canadian Academy of Engineering (Written Submission).

[14] RNNR Evidence: Fogwill (CERI); Pineau (HEC Montreal); Cameron (QUEST); Eggerston (Canadian Association for Renewable Energies); Fox (NEB); Peterson (StatsCan); Patrick Bateman (Director, Canadian Solar Industries Association, Canadian Council on Renewable Electricity [CanCORE]); Gonçalves (ECCC); Israël (Pembina Institute); Vaillancourt (Canadian Academy of Engineering); Lightburn (Suzuki Foundation); and Alison Thompson (Chair of the Board, Canadian Geothermal Energy Association).

[15] RNNR Evidence: Abha Bhargava (Director, Energy Integration, NEB); Egan (Canadian Gas Association); Birn (IHS Markit); Millard (IEA); Vaillancourt (Canadian Academy of Engineering); and DeRochie (Environmental Defence).

[16] RNNR Evidence: John Conti (Deputy Administrator, U.S. Energy Information Administration [U.S. EIA]); Eggerston (Canadian Association for Renewable Energies); Zindler (Bloomberg); Luiken (IEEE); Bateman (CanCORE); and the Canadian Academy of Engineering (Written Submission).

[17] RNNR Evidence: Theresa McClenaghan (Executive Director and Counsel, Canadian Environmental Law Association).

[20] RNNR Evidence: Bradley (Canadian Electricity Association); Pineau (HEC Montreal); Conti (U.S. EIA); Keating (Nalcor Energy); Mustard (Researcher); Vaillancourt (Canadian Academy of Engineering); Cameron (QUEST); Egan (Canadian Gas Association); Dusyk (Pembina Institute); Feinstein (Lake Ontario Waterkeeper); DeRochie (Environmental Defence); Péloffy (Quebec Environmental Law Centre); McClenaghan (Canadian Environmental Law Association); Romero (Clean Resource Innovation Network); Lightburn (Suzuki Foundation); Dwarkin (RS Energy Group); Layzell (CESAR); and Bateman (CanCORE).

[21] RNNR Evidence: Bradley (Canadian Electricity Association); Layzell (CESAR); Fogwill (CERI); Lourie (Ivey Foundation); Dusyk (Pembina Institute); Mustard (Researcher); Feinstein (Lake Ontario Waterkeeper); Lightburn (Suzuki Foundation); Gattinger (University of Ottawa); Pineau (HEC Montreal); and DeRochie (Environmental Defence).

[22] RNNR Evidence: Greg Peterson (StatsCan) and Dusyk (Pembina Institute).