FEWO Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Challenges Faced by Women Living in Rural, Remote and Northern Communities in Canada

Introduction

Living in rural, remote and northern communities in Canada can pose some unique challenges. For women, these challenges can include difficulty accessing or having a wide choice of employment; ensuring their safety and security, including their ability to leave violent relationships and find safe shelter; and accessing programs and services such as healthcare, mental health and counselling services, education and childcare. As well, the lack of access to reliable and affordable high-speed Internet can exacerbate challenges women living in rural, remote and northern communities experience in all aspects of their lives. Recognizing this situation, the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women (the Committee) agreed:

That, pursuant to Standing Order 108(2), the committee undertake a study examining the challenges faced by women living in rural communities, including, but not limited to access to social services; access to public safety and emergency services; and access to emergency shelters. That the study consider the different circumstances encompassed within rural communities; that the study acknowledge the unique circumstances of Indigenous women in rural communities; that the committee report its findings to the House, and pursuant to Standing Order 109, the committee requests that the government table a comprehensive response to the report.[1]

This study was held between 1 December 2020 and 27 April 2021. During this time, the Committee heard from 18 witnesses: seven witnesses appeared as individuals and 11 witnesses represented community organizations, associations, postsecondary education institutions, and local governments. The Committee also received two written briefs. The Committee acknowledges the underrepresentation of Indigenous women’s voices in this study and regrets that their voices are not better included in this report.

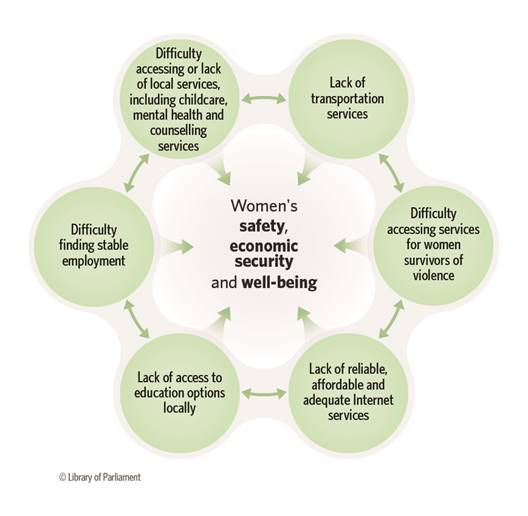

The Committee would like to note that, while this report divides challenges and issues in stand-alone sections, they are interconnected. Katie Allen, appearing as an individual, said:

With limited options for diverse, stable employment and post-secondary education and training required to attain higher-paying employment, rural women and youth are often stuck with making difficult choices about where and what education and employment opportunities they can access, creating a vicious cycle of low wages, few opportunities, unsuitable housing and insufficient transportation. These factors, combined with limited emergency and second-stage housing for women and children, also produce significant health and safety risks for rural women looking to leave unstable home environments and gender-based violence.[2]

Figure 1—Selected Factors That Affect the Safety, Economic Security and Well-Being of Women Living in Rural, Remote and Northern Communities

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament on 1 June 2021.

Therefore, solutions addressing challenges faced by women living in rural, remote and northern communities in Canada must recognize this interconnectedness.

Ensuring Women’s Safety and Security

Women living in rural, remote and northern communities face unique barriers regarding safety and security, including challenges when leaving violent relationships or trying to protect themselves from crime, as described in the sections below.

Intimate Partner Violence and Violence against Women

The real cost of gender-based violence is this. Half of all women over the age of 16 in Canada have experienced at least one incident of physical or sexual violence. Approximately every six days, a woman in Canada is killed by her intimate partner; [I]ndigenous women are killed at six times that rate. In April 2020, seven out of 10 women reported being concerned or extremely concerned about violence at home as a result of COVID‑19.

Vicki‑May Hamm, Mayor, Ville de Magog FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 16 February 2021, 1125

Violence against women continues to be a problem in all communities in Canada. While it is difficult for all women to report and leave violent relationships, women living in rural, remote and northern communities face particular challenges in reporting this violence. Challenges include lack of confidentiality; fear of firearms;[3] and difficulty accessing Internet services,[4] transportation and shelters or adequate housing.

The Committee heard that because “[e]verybody knows everybody” in small communities, women might worry others will not believe in the abuse, authorities may be reluctant to get involved due to social ties, or people who know violence is happening may be afraid of repercussions from the abuser.[5] Women leaving violent relationships might have a difficult time finding new housing since other people knew the abuser.[6] However, Fern Martin, appearing as an individual, explained that because rural and remote communities are smaller, women may have an easier time finding informal support.[7]

Witnesses emphasized that a lack of transportation options is a significant barrier to women leaving a violent relationship.[8] Jean Bota, Councillor, Red Deer County, explained that, in her area, many “agencies operate on shoestring budgets, and they cannot afford the extra cost of transportation.”[9] Katie Allen, appearing as an individual, told the Committee that there is a lack of funding for transportation services in rural communities, including funding for gas, and that it creates barriers for accessing some services.[10]

Witnesses explained that accessing shelters is challenging in rural, remote and northern communities.[11] Shelters for women might not be available or, if they are, they might be full.[12] In a written brief, the Mokami Status of Women Council stated:

Shelters in our community are consistently full which has resulted in overflow into local hotels and individuals being forced to take to the trails in extremely hot weather during the summer months and frigid cold temperatures throughout the winter. Sadly, it is not uncommon for individuals to die on our trails due to unsafe weather conditions and lack of safe housing.[13]

In some cases, women may have to uproot their lives and leave their communities to find shelter or housing, which can be retraumatizing.[14] As well, accessing transition, second‑stage or affordable housing is difficult in rural, remote and northern communities.[15] Lack of stable and affordable housing can make “women even more vulnerable to gender-based violence.”[16] Vianne Timmons, President and Vice-Chancellor of the Memorial University of Newfoundland, stressed the need for more support and funding for transition housing.[17]

The Committee was told that the COVID‑19 pandemic has amplified existing challenges facing women who are trying to escape violent relationships, particularly because of the closures of support services, shelters and transportation.[18] Furthermore, for women who are “stuck at home” with their abuser, reaching out to services may be even more challenging than before the pandemic.[19]

In addition to eliminating the challenges listed above, witnesses recommended that first responders, law enforcement and individuals working in the justice system receive anti-bias training and training on trauma-informed practices, including on how trauma affects women who experience violence.[20] As well, Vianne Timmons stressed the importance of educating men on how to intervene when they see violence against women.[21] She also suggested women should have access to a support person when they meet with law enforcement, “to help counter the re-traumatization.”[22]

The Committee was told that organizations providing supports and services to women living in rural, remote and northern communities are understaffed and do not have the capacity to address the needs in their communities. Therefore, witnesses called for additional funding[23] as well as core funding[24] for women’s organizations in rural, remote and northern communities. Louise Rellis, Administrative and Client Support, Central Alberta Victim and Witness Support Society, also recommended equitable funding of rural and urban organizations.[25] She explained that rural organizations cover larger areas and have to provide a wider range of services than urban organizations.[26]

Therefore, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 1—Services for Women Survivors of Violence

That the Government of Canada work with provincial and territorial governments to identify needs and gaps to provide targeted operational and core funding to shelters and transition houses in rural, remote and northern communities to close the shortage of support for women affected by violence.

Recommendation 2—Services for Women Survivors of Violence

That the Government of Canada increase its investments, and where possible collaborate with provinces and territories, in the creation of more emergency, second stage, transition and affordable housing in rural, remote and northern communities to better assist women affected by violence through various stages of their exit and restoration strategies.

Recommendation 3—Services for Women Survivors of Violence

That the Government of Canada work with provincial and territorial governments to ensure that organizations located in rural, remote and northern communities and providing services to women, including shelter as well as mental health and counselling services, receive funding:

- that is equitable when compared to that received by organizations located in urban communities;

- that allows shelters serving women located in rural, remote and northern communities to provide services that respond to the needs of women, including providing additional shelter beds; and

- for projects aiming to increase transportation options for women when they want to leave a violent relationship.

Recommendation 4—Training for Law Enforcement

That the Government of Canada require that Royal Canadian Mounted Police officers receive training that is adapted to the reality of women as well as anti-bias and trauma‑informed training to improve their responses to calls for help that relate to violence against women.

Crime in Rural Communities

The Committee heard that crime in rural communities has been increasing.[27] Some witnesses poignantly shared their ongoing feelings of fear, and that they are exhausted, powerless and frustrated regarding crime in their communities.[28] They explained that for women living in rural communities, being alone at home is causing fear and anxiety, particularly for women who have been victims of crime.[29] Wendy Rewerts, appearing as an individual, explained:

Many of these criminals are now carrying guns, knives, machetes and who knows what else. This is very unnerving when during busy farm seasons, the women are home alone long into the night. We are nervous when a vehicle drives by slowly, wondering if it is just going by, looking to see if anyone is home, or is it just an innocent person driving by.[30]

The Committee was told that some factors unique to rural, remote and northern communities affect law enforcement and emergency services’ ability to respond to emergency calls. For instance, police detachments may be located very far from some homes[31] and many homes may not have a clear street address.[32] Both of these factors may lengthen the response time of law enforcement and emergency services, which can contribute to the underreporting of crime.[33] Witnesses also explained that because of recurring crime, individuals living in rural communities may have to shoulder the financial burden of expensive insurance policies and of installing security and surveillance systems.[34] If they are victims of crime repeatedly, some individuals may become unable to find insurance to cover their belongings and properties.[35] Witnesses indicated more law enforcement officers are needed to cover large rural areas in Canada.[36] The Committee notes that through Police Service Agreements, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) provides policing services in eight provinces, three territories and approximately 150 municipalities. Under these agreements, provinces and municipalities establish the “level of resources, budget and policing priorities in consultation with the RCMP;” the RCMP is then “responsible for fulfilling the policing priorities within the established budget.”[37]

The Committee was told that the current sentences for criminal offences do not deter crime in rural communities.[38] Witnesses recommended sentences be more severe, particularly for repeat offenders.[39] As well, delays within the justice system, including delays caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, can lead to individuals continuing to commit crimes while their cases are being processed.[40]

Therefore, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 5—Law Enforcement Response Times

That the Government of Canada work with provinces and municipalities with which it has Police Service Agreements to improve Royal Canadian Mounted Police services, including closing the gap in response times for calls in rural, remote and northern communities.

Improving Women’s Well-being and Economic Security

Without access to [critical] services in their local communities, rural women face poorer outcomes across the board in terms of their social and economic well-being, health and safety, and engagement in decision‑making processes that impact their lives.

Katie Allen, As an individual

FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 16 February 2021, 1105

The exodus of young people to larger and urban centres creates challenges for rural, remote and northern communities across the country. For example, the Committee heard that inclusivity remains a challenge in rural communities: for that reason, many lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and Two-Spirit (LGBTQ2) individuals move to urban centres after high school.[41] Vicki‑May Hamm, Mayor of the Ville de Magog, explained that the vitality of rural communities in Canada depends on their ability to generate economic growth and to “attract and retain youth,” immigrants and Indigenous peoples.[42] To attract and retain residents, rural communities must provide the right supports, such as shelters, counselling, childcare, transportation and education.[43] The following sections describe some of the challenges women living in rural, remote and northern communities are facing and propose solutions.

Improving Access to and Choice of Employment

The Committee heard that opportunities for employment are limited in rural communities.[44] Katie Allen explained that “the composition of rural economies and labour market landscapes impacts employment quality, often producing conditions that lead to precarious employment.”[45] Because of limited and precarious employment opportunities, as well as limited education and training options, women living in rural communities can become stuck in a “vicious cycle of low wages, few opportunities, unsuitable housing and insufficient transportation.”[46]

As well, the Committee heard that the lack of access to reliable, high-speed Internet services in rural, remote and northern communities can impede women from accessing all types of employment, including e‑commerce and employment for which you can work from home,[47] or for retraining for a new type of employment.[48] According to Shealah Hart, National Youth Council Member of BGC Canada, the COVID‑19 pandemic has shown that many types of employment can be adapted to a work-from-home format, if reliable high-speed Internet is accessible; this situation opens opportunities for women in rural communities to build and manage small businesses from home.[49] Peter Maddox, President of the Direct Sellers Association of Canada, added that the lack of access to reliable, high-speed Internet “takes away an economic opportunity that should be for all.”[50] For example, Adrienne Ivey, appearing as an individual, explained that she has had to close her agricultural communications business because she “cannot count on a reliable connection, and for the limited data that we do have access to, I need to stockpile it for the days and weeks that our kids may require that data for online schooling.”[51] Melissa O’Brien, Manager, Communications and Stakeholder Relations, Southwestern Integrated Fibre Technology, emphasized the importance of digital literacy and skills training to enable women’s participation in the “technology-driven world.”[52]

To improve access to and options of employment for women living in rural communities, the Committee was told that the federal government should consider non-traditional employment and earning opportunities, such as direct selling, when developing policies and programs to support workers.[53] As financing can be difficult to access for women entrepreneurs,[54] the federal government should provide grants to women who are interested in launching a business.[55] As well, Shealah Hart recommended that the Government of Canada work with provincial and territorial governments to support rural communities in the development of their economies.[56]

Therefore, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 6—Funding for Women Entrepreneurs

That the Government of Canada, through its existing funding programs for entrepreneurship, provide increased funding for women entrepreneurs, particularly for women who are starting businesses, including online businesses, in rural, remote and northern communities.

Recommendation 7—Digital Literacy and Skill Training

That the Government of Canada provide funding to projects that aim to provide digital literacy and skills training to women living in rural, remote and northern communities, with the goal of ensuring that women have access to educational opportunities and the skills needed to participate in the digital economy and improving women’s economic security.

Increasing Access to Services and Supports

The Committee heard that women living in rural, remote and northern communities face unique challenges in accessing services and supports when compared to women living in larger and urban centres. These challenges include, for example, lack of access to affordable transportation, housing and childcare, as well as lack of access to healthcare, food and Internet services.[57] According to Katie Allen:

Regionalization and the downloading of responsibilities to local government, non-profit and charitable organizations—without the matched support of funding—has had significant impacts on women’s ability to access critical health, social and justice services. Additionally, the closure of schools and postal offices, the loss of local infrastructure like gas stations, and limited access to broadband and telecommunications infrastructure continue to further isolate rural women from critical services.[58]

Louise Rellis explained that these services are often “routed to larger towns and cities.” She added that many urban organizations receive funding to organize outreach programs to support rural communities but that the supports and services offered “are often not adaptable to different challenges” in rural communities.[59] In a written brief, the Canadian Union of Postal Workers shared some ways in which post offices could help increase access to services in “rural, remote and reservations areas,” including transforming them into “community hubs” that provide Internet access and online banking, and offering spaces for artisans and entrepreneurs to promote their work.[60]

A lack of access to relevant services in their communities can cause feelings of isolation and loneliness among women[61] and can negatively affect their social and economic well-being.[62] Traci Anderson, Executive Director of BGC Kamloops, noted that there is a need for “wraparound supports that [address] all of the intersecting issues to sustain rural communities and their prosperity in the long term.”[63]

The Committee was told that addressing challenges faced by women living in rural communities with a “one-size-fits-all approach” does not work.[64] Specifically, witnesses stressed the importance of collecting data on various population groups based on age, gender and race, for example, to be able to adapt programs and services to the needs of diverse communities.[65] The Committee heard that there are important data gaps about rural communities, which can impede the implementation of “evidence-informed responses,”[66] including data gaps on the differentiation between “rural, rural remote, and remote communities” and on Indigenous peoples.[67] As well, the Committee heard that the Government of Canada should use an equity‑based approach that recognizes the needs of diverse populations and communities in the country.[68]

Therefore, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 8—Gender-Based Analysis Plus

That the Government of Canada ensure that complete gender-based analysis plus is applied in the development, implementation and review phases of all programs and services, with the goal of ensuring that such programs and services respond to the unique needs of women and diverse individuals living in rural, remote and northern communities.

Recommendation 9—Data Collection

That the Government of Canada improve the collection of disaggregated data about rural, remote, Indigenous, and northern communities, and provide public access to this data.

Recommendation 10—Increasing Access to Services and Supports

That the Government of Canada review and implement the recommendations put forward by the Canadian Union of Postal Workers outlined in Delivering Community Power, including expanding services such as, but not limited to, using post offices as community hubs, establishing senior check-ins and expanding the mandate of Canada Post to re-establish Postal Banking.

Access to Childcare Services

The Committee heard that access to quality and affordable childcare options is essential for parents to find work or to pursue education.[69] In rural, remote and northern communities, there might not be childcare providers in all communities; parents might therefore have to “leave their community to bring their children to reliable child care.”[70] Witnesses emphasized the importance of offering affordable and flexible childcare options to respond to the needs of all parents and communities.[71] For instance, Traci Anderson stated:

I think that's integral for this plan. As it rolls out, it really needs to be diverse. There needs to be inclusion for flexible childcare. Parents don't work nine to five, and especially since the pandemic, we're learning that there are a lot of flexible work schedules now, so childcare needs to work to fit that. We absolutely believe that it can't be a one-size-fits-all approach, and as I said, things are compounded for rural communities.[72]

As well, the Committee was told that wages need to be increased and more equitable in the childcare sector to attract more workers: since wages are generally low, workers often leave the sector to find employment in higher-paying sectors of the economy.[73] Traci Anderson indicated that “early childhood education needs to be reimagined in a creative way that would draw more people into the sector.”[74] Debbie Zimmerman, Chief Executive Officer of Grape Growers of Ontario, told the Committee the Government of Canada should look at different delivery models for implementing childcare services in Canada, such as those in Quebec and in Scandinavian countries.[75]

Therefore, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 11—Childcare Services

That the Government of Canada, in collaboration with provinces and territories, ensure that the Canada-wide Early Learning and Child Care Plan responds to the needs of parents living in rural, remote and northern communities, including the need for affordable and flexible childcare options.

Access to Healthcare Services

The Committee heard that women living in rural, remote and northern communities face additional barriers to accessing healthcare when compared to women living in urban centres. For instance, such barriers include difficulty accessing specialized medical services that are often only available in larger and urban centres,[76] which is costly and time-consuming for patients.[77] As well, witnesses indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic has transferred some healthcare services online, or expanded accessibility to virtual healthcare services in cases where they were already available.[78] This shift underlines the importance of access to high-quality Internet services.[79] Witnesses stressed the importance of ensuring healthcare services are available to women living in rural communities, including reproductive health services.[80]

The Committee was also told that there are not enough supports for mental health in rural communities.[81] For example, the Committee heard that there has been an increase in drug use and overdoses in rural and First Nations communities, especially with respect to opioids; this situation is the result “of isolation, long distances from emergency services and limited access to support, resources and education.”[82] Angèle McCaie, General Manager of the Village of Rogersville, stated that communities need resources to be able to provide mental health services locally and in a timely manner.[83]

Access to Education

The Committee was told that accessing and paying for post-secondary education can be a challenge for individuals living in rural, remote and northern communities. For instance, required courses may not be available locally and/or lack of access to reliable, high-speed Internet services might make it difficult to access education materials.[84] Differences in the types of employment for young women and men living in rural and northern communities can affect students’ ability to pay for post‑secondary education: young women tend to work in sectors (retail, tree planting and babysitting, for example) that pay less than those in which young men tend to work (mining, for example).[85] The Committee heard that it is important to ensure that post-secondary education is financially accessible to all students in Canada, including through providing financial aid with bursaries.[86]

The Committee heard about the effects of the lack of reliable Internet services on access to education, both for children and women. Vianne Timmons stated that “the lack of access [to reliable Internet] is the biggest challenge in education for working women, young mothers or women in mid-career who need to pivot and change.”[87] As well, Adrienne Ivey stated that, as a mother, “it is devastating to watch our children struggle to keep up with their classmates online solely because of a lack of connectivity.”[88] In addition, she noted that there is a “disconnect” between children living in rural areas and children living in urban areas in terms of the comfort level they have using technology.[89]

Access to Legal and Justice Services

The Committee was told that access to legal and justice services, including services in French, are limited for individuals living in rural, remote and northern communities.[90] For example, the Mokami Status of Women Council explained that the lack of correctional services in Labrador forces offenders to go to a correctional institution located in Newfoundland for the duration of their sentences. This means “women have to leave their supports, mothers are obligated to leave their children and employees are forced to leave their jobs. This is systemic racism.”[91] Furthermore, the organization indicated that “[w]hen the way justice is enforced is not culturally appropriate and community focused, offenders are further traumatized.”[92] They added that Indigenous groups have been asking for restorative justice options to be made available for a long time, but that it “was not happening.”[93] The Mokami Status of Women Council stressed the importance of supporting and funding the organizations working to provide legal and justice services in isolated communities.[94]

As well, the Committee heard that accessing services in French can be challenging for women living in rural, remote and northern communities, a situation that can have important consequences in the case of legal- and justice-related services.[95] Renée Fuchs, President of the Centre Victoria pour femmes, shared the story of a woman whose testimony in a sexual assault case could not be heard because a judge declared a stay of proceedings for unreasonable delay, delays “mainly attributable to the fact that, because of a number of failures in the system, no francophone interpreter had been scheduled for that trial.”[96] She added that “[t]estifying about a traumatic event in one's own language is not a privilege, it's a right.”[97] She stated that increasing the number of people in designated bilingual positions within the justice system is necessary.[98]

Access to High-Speed Internet

As a society, we have some brilliant ways of maintaining our lives while social distancing: virtual health care, online therapy, Zoom social gatherings, virtual gyms and places of worship and ordering groceries online. While that is a list to be proud of as a country, sadly, it is a list that strikes anxiety into the hearts of rural women. We cannot access most of these things on any given day.

Adrienne Ivey, Farmer, As an individual

FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 23 February 2021, 1100

Although past and current federal governments, in collaboration with provinces and territories, have invested in expanding access to broadband in Canada, witnesses shared that access to high-speed Internet services is still an issue in rural, remote and northern communities across the country. Lack of access to reliable and affordable high-speed Internet can exacerbate challenges women living in rural, remote and northern communities’ experience in all aspects of their lives, as explained in previous sections of this report: it can be a barrier to or prevent women from securing particular types of employment or from launching a business online, leaving violent relationships and seeking help to do so, and accessing essential services such as healthcare and education. Katie Allen stated that the “limited access to broadband and telecommunications infrastructure continue to further isolate rural women from critical services.”[99] Melissa O'Brien explained that the COVID‑19 pandemic has exacerbated connectivity challenges and amplified the digital divide between rural and urban communities in Canada.[100] She stated: “With many more people now required to work from home, education increasingly being offered remotely, video conferencing replacing face-to-face interactions and health services and programs continuing to move to online platforms, access to high-speed Internet has now become essential.”[101] In addition to availability, witnesses indicated that the affordability of Internet services in rural communities can be a factor limiting access.[102]

The Committee heard that funding broadband infrastructure “needs to be seen as an investment rather than a cost.”[103] Melissa O'Brien noted that “[e]quitable and affordable connectivity is vital for empowering women and can be a powerful tool for creating a greater space for female inclusion in today's ever-growing digital society.”[104] Therefore, she told the Committee that Internet services need to be affordable and recommended ongoing support be provided for the Government of Canada’s Connecting Families initiative or for similar initiatives.[105] In addition to recommending increased funding for broadband infrastructure in Canada,[106] witnesses indicated that there is a need for greater collaboration between all levels of government, residents and the private sector to improve access to broadband in Canada.[107]

Therefore, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 12—Improving Access to Broadband Internet Services

That the Government of Canada continue to increase funding for the development of broadband infrastructure in rural, remote and northern communities, with the goal of ensuring that individuals living in those communities have access to affordable, high-speed Internet services equivalent to individuals living in urban communities.

[1] House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women (FEWO), Minutes of Proceedings, 27 October 2020.

[2] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 16 February 2021, 1105 (Katie Allen, As an individual).

[3] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 1 December 2020, 1210 (Fern Martin, As an individual).

[4] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 2 February 2021, 1205 (Louise Rellis, Administrative and Client Support, Central Alberta Victim and Witness Support Society).

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid., 1240.

[8] Ibid., 1210; FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 16 February 2021, 1115 (Jean Bota, Councillor, Red Deer County).

[10] Ibid., 1155 (Katie Allen).

[12] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 1 December 2020, 1250 (Vianne Timmons, President and Vice‑Chancellor, Memorial University of Newfoundland); Mokami Status of Women Council, “Challenges Faced by Women Living in Rural Communities—Submission to the Standing Committee on the Status of Women,” Written Brief.

[13] Mokami Status of Women Council, “Challenges Faced by Women Living in Rural Communities—Submission to the Standing Committee on the Status of Women,” Written Brief.

[15] Mokami Status of Women Council, “Challenges Faced by Women Living in Rural Communities—Submission to the Standing Committee on the Status of Women,” Written Brief.

[16] Ibid.

[18] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 16 February 2021, 1155 (Katie Allen) and 1125 (Vicki-May Hamm, Mayor, Ville de Magog).

[20] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 1 December 2020, 1215 and 1220 (Vianne Timmons) and 1220 and 1255 (Fern Martin); Mokami Status of Women Council, “Challenges Faced by Women Living in Rural Communities—Submission to the Standing Committee on the Status of Women,” Written Brief.

[22] Ibid., 1220.

[23] Ibid., 1250; FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 16 February 2021, 1125 (Vicki-May Hamm).

[24] Ibid., 1105 (Katie Allen); FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 2 February 2021, 1235 (Louise Rellis).

[26] Ibid.; FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 1 December 2020, 1250 (Angèle McCaie, General Manager, Village of Rogersville).

[27] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 2 February 2021, 1200 (Lorie Johanson, As an individual) and 1200 (Wendy Rewerts, As an individual); FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 23 February 2021, 1100 (Gail Kehler, Rancher, As an individual).

[28] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 2 February 2021, 1200 (Lorie Johanson) and 1200 (Wendy Rewerts); FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 16 February 2021, 1115 (Jean Bota); FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 23 February 2021, 1105 (Pamela Napper‑Beamish, As an individual).

[29] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 2 February 2021, 1205 and 1215 (Louise Rellis) and 1200 (Wendy Rewerts).

[30] Ibid., 1200 (Wendy Rewerts).

[33] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 2 February 2021, 1240 (Lorie Johanson) and 1230 (Louise Rellis).

[34] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 23 February 2021, 1100 (Gail Kehler) and 1105 (Pamela Napper‑Beamish).

[36] Ibid., 1245 (Louise Rellis); FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 23 February 2021, 1135 (Gail Kehler).

[37] Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Contract Policing.

[38] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 23 February 2021, 1100 (Gail Kehler); FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 2 February 2021, 1200 (Wendy Rewerts).

[39] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 23 February 2021, 1100 (Gail Kehler); FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 2 February 2021, 1215 (Wendy Rewerts).

[40] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 23 February 2021, 1105 (Pamela Napper‑Beamish); FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 2 February 2021, 1215 (Louise Rellis).

[43] Ibid., 1115 (Jean Bota).

[44] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 2 February 2021, 1115 (Peter Maddox, President, Direct Sellers Association of Canada); FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 27 April 2021, 1115 (Shealah Hart, National Youth Council Member, BCG Canada).

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid., 1140 (Vicki-May Hamm); FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 23 February 2021, 1110 (Melissa O'Brien, Manager, Communications and Stakeholder Relations, Southwestern Integrated Fibre Technology).

[48] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 2 February 2021, 1125 (Debbie Zimmerman, Chief Executive Officer, Grape Growers of Ontario).

[51] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 23 February 2021, 1100 (Adrienne Ivey, Farmer, As an individual).

[52] Ibid., 1110 and 1145 (Melissa O'Brien).

[57] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 2 February 2021, 1205 (Louise Rellis); FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 16 February 2021, 1105 (Katie Allen).

[60] Canadian Union of Postal Workers, “Positive Impacts of a Re‐imagined Public Post on Rural Women,” Written Brief, 18 March 2021.

[65] Ibid., 1155 (Renée Fuchs, President, Centre Victoria pour femmes) and 1125 and 1155 (Vicki-May Hamm).

[66] Ibid., 1105 (Katie Allen).

[67] Ibid., 1145.

[68] Mokami Status of Women Council, “Challenges Faced by Women Living in Rural Communities—Submission to the Standing Committee on the Status of Women,” Written Brief.

[69] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 1 December 2020, 1240 (Vianne Timmons); FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 2 February 2021, 1135 (Debbie Zimmerman) and 1205 (Louise Rellis); FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 27 April 2021, 1115 (Traci Anderson).

[71] Ibid., 1125 and 1135.

[72] Ibid., 1125.

[73] Ibid., 1120 and 1145.

[74] Ibid., 1130.

[75] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 2 February 2021, 1135 and 1155 (Debbie Zimmerman).

[76] Ibid., 1205 (Louise Rellis); FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 27 April 2021, 1155 (Traci Anderson).

[77] Mokami Status of Women Council, “Challenges Faced by Women Living in Rural Communities—Submission to the Standing Committee on the Status of Women,” Written Brief.

[79] Ibid., 1120 (Melissa O'Brien); Mokami Status of Women Council, “Challenges Faced by Women Living in Rural Communities—Submission to the Standing Committee on the Status of Women,” Written Brief.

[80] FEWO, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, 1 December 2020, 1255 (Angèle McCaie) and 1250 (Fern Martin).

[84] Ibid., 1225 (Vianne Timmons).

[85] Ibid., 1230.

[86] Ibid., 1200 and 1240.

[87] Ibid., 1225.

[89] Ibid., 1145.

[90] Mokami Status of Women Council, “Challenges Faced by Women Living in Rural Communities—Submission to the Standing Committee on the Status of Women,” Written Brief.

[91] Ibid.

[92] Ibid.

[93] Ibid.

[94] Ibid.

[96] Ibid., 1110.

[97] Ibid., 1110.

[98] Ibid., 1135.

[101] Ibid.

[102] Ibid.

[105] Ibid.