FEWO Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Act Now: Preventing Human Trafficking of Women, Girls and Gender Diverse People in Canada

Introduction

Recognizing that human trafficking occurs in Canada, and that women, girls and gender diverse individuals are disproportionately affected by these crimes, the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women (the Committee) undertook a study with the goal of improving Canada’s approach to addressing and preventing human trafficking, as well as supporting victims and survivors.[1] Between 20 March and 18 May 2023, the Committee heard from 55 witnesses and received 57 written submissions. Representatives from Statistics Canada, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, the Department of Justice Canada, Women and Gender Equality Canada, Public Safety Canada, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and Canada Border Services Agency provided testimony. In addition, the Committee traveled to Vancouver, the Greater Toronto Area, Sault Ste. Marie and Halifax to meet with organizations and services working to combat human trafficking in Canada. A table outlining the various services that were presented to the Committee during its travel can be found in Appendix A.

Testimony, written submissions, and informal meetings and site visits have informed the Committee’s report and highlighted certain focus-areas. Notably, this study and the resulting report focus predominantly on human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation, however, other forms of trafficking are also discussed. The report is structured into four sections:

- Context and background information, including legal frameworks, terminology and data;

- Systems of oppression that affect human trafficking in Canada;

- Improving services for survivors of human trafficking; and

- Preventing human trafficking in Canada.

Context and Background

The Committee was provided valuable context about the terminology used in legislation and policies, the overall trends and data on human trafficking in Canada, and the legal mechanisms related to human trafficking in Canada. These topics are briefly outlined below.

Overview: Terminology and Concepts

The Committee heard a diversity of perspectives on human trafficking in Canada throughout its study. While witnesses predominantly discussed human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation in Canada, various definitions and understandings of key terminology were presented. The concepts that were discussed during the study included human trafficking with a focus on sex trafficking and sexual exploitation as well as sex work. The following sections provide an overview of various witness perspectives on these concepts.

When speaking about human trafficking, which could include “everything from forced labour to sexual exploitation,”[2] witnesses noted that this crime includes the violation of an individual’s human rights and freedom of choice, by a “third party”[3] or “trafficker” typically for the trafficker’s “personal gain.”[4] Violence, exploitation, coercion, deception and force were often used in the description of human trafficking.[5] In a written brief, Legal Assistance of Windsor and Sisters of St. Joseph of Toronto explained that:

Human trafficking is a violent experience along a spectrum of exploitation, compounded by intersecting individual circumstances and systemic oppressions. Within this spectrum, people can experience a range of violations and crimes against them, including labour law violations, human rights violations, criminal code violations, and human trafficking.[6]

Kate Price, Executive Director of the Action Coalition on Human Trafficking Alberta Association, explained that very rarely is the “true definition of trafficking” understood.[7] In addition, Angela Wu, Executive Director of SWAN Vancouver, Canadian Alliance for Sex Work Law Reform, noted that current definitions are “broad and ambiguous,” encompassing many different “issues” and impeding the creation and implementation of “tailor[ed] solutions to the actual problem.”[8] Kate Price further explained that the ways in which trafficking is defined are “wildly inaccurate” compared to “what we are seeing on the front lines” and that the experiences of consensual sex workers are “vastly different” from her clients who have experienced sexual exploitation.[9] As such, the Committee was told that developing a clear and consistent understanding of the concept is important. Regarding the inconsistency in terminology and in the understandings of these, Jenn Clamen, the National Coordinator of the Canadian Alliance for Sex Work Law Reform explained that the term human trafficking is being used by many to “describe everything from intimate partner violence to sex work to labour exploitation.”[10] Inconsistency in terminology can lead to complicated statistics and data collection, making it harder to gauge levels of human trafficking in Canada.

Therefore, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 1

That the Government of Canada amend anti-trafficking laws, policies and programs to differentiate between consensual sex work, sex trafficking and sexual exploitation of minors.

Recommendation 2

That the Government of Canada ensure that any existing and new federal policies addressing human trafficking clearly define the concept within human trafficking, including human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation and sexual exploitation of minors, to avoid the conflation of these terms with other concepts such as consensual sex work.

Distinguishing Between Sex Work and Human Trafficking for the Purpose of Sexual Exploitation

While witnesses acknowledged that there are various types of human trafficking occurring in Canada, many focused on human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation, referred to as “sex trafficking” by some witnesses. The Committee heard diverse perspectives on human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation. Some witnesses explained that the sex industry—and the demand that it creates—are inextricably linked to the persistence of sex trafficking and sexual exploitation in Canada.[11] Among witnesses who presented this perspective, several noted that all interactions in the sex industry are underpinned by coercion and/or exploitation of some kind; for example, the Coalition for the Abolition of Prostitution stated that “in reality, the sexual act obtained by sex buyers is always coerced.”[12]

In contrast, other witnesses told the Committee that consensual sex work and sex trafficking are not equivalent.[13] For example, Julia Drydyk, Executive Director, Canadian Centre to End Human Trafficking, explained that:

Human trafficking is the exploitation of someone else for your personal gain, so not all consensual sex work has anything to do with human trafficking. In fact, they’re completely different. Where we look at human trafficking is when there is another individual who is threatening, coercing and enforcing someone into the commercial sex industry and where they are profiting. It’s also where you see individuals not feeling able to exit, again, because of the fear and the threats imposed on them.[14]

The distinction between sex work and human trafficking was referenced throughout the Committee’s study by various witnesses. Some witnesses explained that generally, sex work is inherently consensual. Therefore, exploitation and absence of choice are not automatically present when someone is working as a sex worker.[15] Kate Sinclaire, Member, Sex Workers of Winnipeg Action Coalition, stated that:

It’s very important to understand that people make their choices for different reasons. Just because it’s a choice that someone else wouldn’t make doesn’t automatically make it trafficking.[16]

She further explained that, from her perspective, trafficking may occur if an individual is in sex work and did not make the choice to be there; however, she added that survival sex work, or individuals engaging in sex work based on “survival choices” should not be labelled as trafficking.[17] In a written submission, Freedom United defined terms in the following way:

Sex work describes an informed transaction between consenting adults engaging in sexual activities. Like in other labour sectors where trafficking and forced labour occur, trafficking for sexual exploitation happens when coercion, threat and manipulation are present, and the threshold is met under the definition set out in the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children.[18]

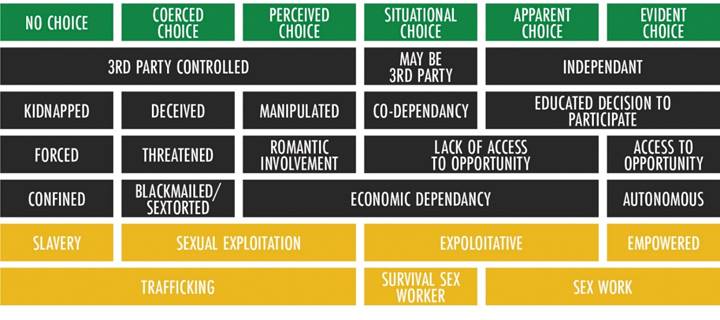

Kathleen Quinn, the Executive Director of the Centre to End All Sexual Exploitation acknowledged that there is a continuum of consent in sex work; however, from her perspective sex workers who have “autonomy, no trauma history, no poverty and high negotiating control” is a “small minority of people” with the majority of individuals in the industry falling under the survival sex work circumstance.[19] However, individuals’ voices should be prioritized and trusted, as they are the experts on their own experiences and needs.[20] Figure 1 provides one perspective on a visual representation of this continuum.

Figure 1—The Spectrum of Choice

Source: This figure was reproduced by the Library of Parliament with permission, based on the figure presented in Hearing Them: African Nova Scotian and Black Experiences of Sex Work, Childhood and Youth Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Human Trafficking in Nova Scotia.

Sandra Wesley, Executive Director of Stella, l'amie de Maimie, explained that sexual exploitation, assault and violence occurs in the sex industry, but she emphasized that the victims of these crimes are sex workers who are left vulnerable due to a lack of labour standards and safety for workers in the industry.[21] She stated:

When we as a group do not have access to basic labour standards, when we don’t have minimum wage, when we don’t have any maximum working hours, when we don’t have sick pay, vacation pay, maternity leave or access to occupational health and safety, it is impossible to even start to talk about what trafficking could possibly look like in such an industry. Trafficking is a concept that is useful when we are talking about workers who have rights and things that go outside of the norm. Focusing on trafficking hides the violence that we actually experience. We are telling you there are serial killers who are murdering us and that’s not interesting. If we don’t phrase it as trafficking, no one cares.

The Committee heard that the conflation of sex work and sex trafficking and exploitation—and the sole focus on trafficking—can be harmful to sex workers.[22] The Committee was told that individuals who are perceived to be engaging in sex work often face stigma.[23] Victims of human trafficking who are involved in the sex industry may experience this stigma as well. Witnesses emphasized the importance of reducing the stigma around sex work, as well as the conflation of sex work with sex trafficking and exploitation.[24] Jessica Stone, Project Manager, Yukon Status of Women Council, explained that “when all violence experienced by sex workers is mislabeled and understood as trafficking, we create a false narrative and we perpetuate harm.”[25] During its travel, the Committee heard perspectives that reinforce this statement. In a written submission, Living in Community explained that:

When the entire sex industry is understood as sex trafficking, only crimes that meet the trafficking threshold are of interest to police. Crimes such as assault, sexual assault, robbery, and other serious crimes are unaddressed. Predators seize this opportunity and act with impunity. When ill-informed antitrafficking strategies such as police raids on massage parlours or hotel stings are applied to sex workers, these increase sex workers’ distrust of and animosity toward police. This results in underreporting of crimes when sex workers actually experience violence or exploitation.[26]

Other witnesses noted that the conflation of these terms can dissuade individuals from reporting crimes they experience. In some instances, individuals may need to self-identify as a victim of trafficking—whether they identify with that term or experience, or not—to access services. In turn, the underreporting, the conflation of terms and the requirement to self-identify as a victim of trafficking can lead to difficulties in accurate data collection. As a result, the statistics related to sexual exploitation and trafficking that are often presented, and applied to policy development and implementation, may be inaccurate or misrepresent the true numbers in Canada.[27]

During discussions of underage victims of human trafficking, some witnesses asserted that young girls are victims of trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation in Canada.[28] Concerns were raised about youths’ vulnerability to exploitation, including grooming and recruitment into human trafficking online and by peers.[29] However, other witnesses cautioned against using trafficking terminology to describe these cases, as any situation involving an individual “under the age of 18 who is engaging in sex work is considered [sexual] exploitation [of a minor]”[30] which should be understood separately from human trafficking.[31] Similarly, minors should not be labelled sex workers, as they are not able to consent to engaging in sex work.

Overview: Human Trafficking in Canada

Witnesses explained to the Committee that because human trafficking data are based on police-reported incidents, these numbers may not be an accurate representation of human trafficking in Canada.[32] Nonetheless, the Committee was told about existing data trends and considerations.

According to the 2021 Statistics Canada report on Trafficking in Persons in Canada, there were 3,541 police-reported incidences of human trafficking between 2011–2021.[33] Over the period from 2011–2017 there was a “year-over-year increase in the number of police-reported incidents” of human trafficking. Statistics Canada cited the 2018–2019 period as having “really high numbers,” which then “flatlined” in 2020–2021.[34] Julia Drydyk added that since “last year’s Human Trafficking Awareness Day, we’ve seen a 50% increase in calls to the [Canadian Human Trafficking] hotline,” adding that the cause of this increase is unknown, but speculated about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and of an increase in public awareness of the issue.[35]

Statistics Canada noted that based on the police-reported data, the type of human trafficking—such as labour trafficking,[36] sex trafficking or a combination—cannot be identified.[37] However, when “other related charges” in reported human trafficking cases were explored, approximately 41% of these incidents involved a secondary offence, with almost six in 10 of these being a “sex trade offence” and one-quarter a sexual assault.[38] Finally, based on Statistics Canada’s police-reported data, nine out of 10 victims of human trafficking “knew their trafficker, and one-third of the victims were trafficked by an intimate partner.”[39]

Canada’s geography may contribute to human trafficking in various ways. Statistics Canada explained that “[b]etween 2011 and 2021, the large majority of human trafficking incidents were reported to police in urban areas. More specifically, since 2011 more than four in 10 of these incidents were reported to police in four cities: Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal and Halifax.”[40] For example, cities in close proximity to major highways that cross borders to the United States may be common trafficking “hubs.”[41] Many witnesses noted that Ontario has high rates of human trafficking;[42] according to the Peel Regional Police, “approximately two-thirds of police-reported human trafficking cases in Canada occur in Ontario, and 62% originate in the Greater Toronto Area.”[43] Community organizations in Sault Ste. Marie emphasized the concentration of human trafficking cases in Ontario, some highlighting the over-representation of Indigenous women, girls and gender diverse people among victims. During its meetings in Sault Ste. Marie, the Committee heard about the effects that the child welfare system can have on Indigenous children, and the ways in which this may lead to complex mental and physical healthcare needs, as well as an increased risk of becoming trafficked or exploited.

Human Trafficking Data Collection

Challenges and limitations related to human trafficking data collection were discussed. Statistics Canada relies on police-reported data and data obtained from shelters across Canada.[44] However, reporting experiences of violence and exploitation to the police is often not a priority for survivors, who are usually looking to access emergency services, such as securing housing.[45] Survivors may not report to police for various reasons, including their previous traumatic experiences, mistrust of polices forces, or the fear of becoming retraumatized or criminalized in the process.[46]

While some individuals involved in the sex industry, including victims of human trafficking, have received valuable support from police and law enforcement, some organizations explained that law enforcement and other individuals in the justice system are included among sex work customers. For example, in 2021, the YWCA Halifax, the Association of Black Social Workers and the Nova Scotia Native Women’s Association, conducted a survey of 149 adult individuals “with either past or present experience in the sex industry.” The publication Hearing Them: Voices and Lived Experiences from the Sex Industry in Nova Scotia provides an overview of Black and African Nova Scotian participants’ responses to this survey. According to the publication, Black and African Nova Scotian adults involved in the sex industry reported that of their customers, 50% were law enforcement officials, 38.9% were professionals such as doctors or lawyers, 38.9% were landlords and/or employers, and 27.9% were political, spiritual or cultural leaders.[47]

In addition, current human trafficking data may be disaggregated by gender and age only. Statistics Canada indicated that these data may be expanded to include ethnicity, indigeneity and immigration status in the coming years.[48] Witnesses highlighted that policymakers and legislators need access to accurate and disaggregated data to adequately respond to human trafficking in Canada. As such, witnesses called for improvements in data collection to obtain comprehensive quantitative and qualitative human trafficking data disaggregated by various identity factors and geographic locations, including rural and remote areas.[49] Kate Price explained that:

[Data collection] requires the survivor to feel safe enough to provide that level of detail to someone who is collecting data. And that is an inherently flawed system to require a survivor to have to share highly painful testimonial in order for the data collection to be improved. I’m not entirely sure what recommendation to make other than to further invest in community-based response services who are able to build the trust and have a nuanced understanding of the regional and cultural needs of the individuals in question and that they may be able to help and assist with data collection.[50]

As well, a representative from Statistics Canada indicated that there is a lack of systems and standards for data collection in addition to challenges sharing information about human trafficking cases across jurisdictions in Canada.[51] Police services may not classify an incident as human trafficking if the survivor does not want to press charges, or if there is insufficient evidence to go forward with human trafficking charges, in which case these cases may be filed under other charges.[52] The representative suggested that the creation of a national database “would lead to establishing comparable standards, processes and information systems” and “would also ensure that [missing persons] cases are in fact reported and investigated more closely.”[53] The Committee was told that Statistics Canada was working with the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police to create this national database.[54]

In addition, Kate Sinclaire explained that current data might include some cases of individuals working in the sex industry consensually but are classified as human trafficking victims.[55] As such, police-reported data is not necessarily an accurate representation of human trafficking in Canada. Building trust within the community, including within the sex work community, is essential to improve data collection.[56]

Therefore, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 3

That the Government of Canada improve the collection of data on human trafficking so that it is disaggregated by identity factors, including disability, race, Indigenous identity, sexuality, immigration status and others, ensuring that the data collection process is culturally safe and trauma-informed for victims and survivors.

Recommendation 4

That the Government of Canada support Statistics Canada to establish a national human trafficking database to allow jurisdictions across the country to access standardized information on perpetrators of human trafficking in Canada.

Groups Facing Elevated Risks of Being Trafficked

The Committee heard that the majority of trafficking cases in Canada involve Canadian citizens, and approximately 70% of police-reported victims are under the age of 25.[57] According to a brief submitted by the National Council of Women of Canada, 25% of victims of human trafficking in Canada are under the age of 18,[58] this statistic was reaffirmed by Statistics Canada.[59] Various witnesses asserted that many human trafficking victims in Canada were young women and girls,[60] pointing to the use of social media and the internet as a possible contributing factor to youth and young adults’ vulnerability to human trafficking.[61]

Witnesses indicated that upwards of 90% of human trafficking cases involved women and girls, as such, they are disproportionately represented among victims and survivors of human trafficking.[62] When examining human trafficking data, Statistics Canada observed that human trafficking is a form of gender-based violence, with the “vast majority” of victims being women and girls.[63] Julia Drydyk added that of the victims and survivors who contact the human trafficking hotline, 2% identify as trans and/or gender diverse individuals, which means that “these groups are eight times more overrepresented in the data relative to their share of the population.”[64]

Witnesses explained that the perpetrators of these crimes are typically men.[65] Regarding individuals charged with human trafficking, eight in 10 accused persons are men and boys.[66] However, Lucie Léonard, Director of the Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics at Statistics Canada explained that a large proportion of young women who are accused of trafficking, were themselves victims of trafficking. Lucie Léonard specified that:[67]

While men represented the large majority of adult accused persons, more than half of the youth accused were girls. Female youth, more and more, are perceived as being better positioned to appear trustworthy and thus are tasked with luring other girls. It is important to note that the boundaries between female trafficking victims and offenders are becoming increasingly blurred. Therefore, a high proportion of the female youth accused of trafficking were themselves victims of human trafficking.[68]

Despite a lack of disaggregated data on human trafficking in Canada, witnesses highlighted certain groups of people who may face elevated risks of exploitation and becoming trafficked, for example:

- Indigenous women and girls;[69]

- Young women and girls;

- Individuals who have interactions with the child welfare system in Canada;[70]

- Individuals with identity factors that may contribute to marginalization and vulnerability, including experiences of poverty and precarious immigration status;[71]

- Individuals living with disabilities;[72]

- International students;

- Black and racialized individuals;[73] and

- Individuals who are Two-Spirit, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex or other sexual minority identities (2SLGBTQI+).[74]

Certain identity factors and experiences may contribute to an individual’s susceptibility to exploitation, these identity factors—some of which are listed above—will be discussed in greater detail in the following section entitled Systems of Oppression and Human Trafficking. Traffickers can use existing vulnerabilities to “groom,” “lure” and “recruit” individuals into human trafficking. Witnesses highlighted some potential approaches and locations that may be common among traffickers for this recruitment process. Traffickers may target schools, universities, bars and online spaces to recruit individuals into trafficking.[75] During its travel, the Committee heard that airports are a location used by traffickers to target, and transport, victims of trafficking. In addition, traffickers may present themselves as a romantic or intimate partner, may promise a pathway to a “better life” for the individual. Finally, traffickers may take steps to ensure that the individual becomes dependent on them, such as the provision of shelter and food, emotional support or drugs.[76]

Overview: Legal Framework

This section will provide a brief overview of legislation in Canada that has been enacted with the purpose of combatting human trafficking. As well, some witnesses spoke about the ways in which these laws affect different populations and made suggestions for amendments to improve existing legislation.

Human Trafficking Legislation in Canada

In 2002, Canada ratified the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons. Article 3 of this protocol defines “trafficking in persons” based on the presence of three elements: “an act, such as recruiting, transporting or harbouring another person,” which is “effected through specific means, such as coercion, abduction, deception or the abuse of positions of vulnerability,” and for the “specific purpose of exploiting that person.” Exploitive conduct is described using examples such as, sexual exploitation or forced labour, which requires proof of coercive practices.[77]

Also in 2002, the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act was amended to include a human trafficking-specific offence that applies in transnational cases only, found in section 118(1). This offence does not require proof of an exploitative purpose; instead, only proof that the accused committed a specific act, such as recruiting, transporting or harbouring a person through specific illicit means, such as abduction, deception, force or coercion, is required.[78]

In 2005, the Criminal Code was amended to include trafficking in persons-specific offences in sections 279.01 to 279.03; the main trafficking offences don’t require proof that the act element was effected through illicit means.[79] Instead, the Act only requires proof that the accused committed a specific act, such as recruiting, transporting or harbouring a person for the purpose of exploitation.[80] Exploitation is understood as occurring when “a reasonable person in the victim’s circumstances would believe that their physical or psychological safety were threatened if they failed to provide the labour or service required of them.”[81]

Several witnesses proposed that the Criminal Code should be amended to more clearly define what constitutes exploitation, some highlighted Bill S-224, An Act to Amend the Criminal Code (Trafficking in Persons).[82] Regarding changes to the Criminal Code, various written submissions suggested that certain sections should be repealed, including section 213,[83] and all records of convictions under sections 210.1, 213(1)(c) and 212 committed prior to 2014 should be expunged.[84]

Regarding penalties under the Criminal Code for individuals convicted of human trafficking, Nathalie Levman, Senior Counsel, Criminal Law Policy Section, Department of Justice, explained that there are often a “significant number of charges” in each human trafficking case.[85] She added that human trafficking provisions “don’t make [the distinction between forced labour and sex trafficking],” but that the majority of human trafficking cases going through courts include sexual exploitation.[86] In human trafficking cases, there are six offences in the Criminal Code that could result in different penalties:[87]

- “Trafficking in Persons (section 279.01): which carries a maximum penalty of life imprisonment and a mandatory minimum penalty of 5 years where the offence involved kidnapping, aggravated assault, aggravated sexual assault or death, and a maximum penalty of 14 years and a mandatory minimum penalty of 4 years in all other cases;

- Trafficking of a person under the age of eighteen years (section 279.011) which carries a maximum penalty of life imprisonment and a mandatory minimum penalty of 6 years where the offence involved kidnapping, aggravated assault, aggravated sexual assault or death, and a maximum penalty of 14 years and a mandatory minimum penalty of 5 years in all other cases;

- Receiving a Financial or Other Material Benefit for the purpose of committing or facilitating trafficking in persons—Adult Victim (subsection 279.02(1)): which carries a maximum penalty of 10 years imprisonment;

- Receiving a Financial or Other Material Benefit for the purpose of committing or facilitating trafficking in persons—Child Victim (subsection 279.02(2)): which carries a maximum penalty of 14 years imprisonment and a mandatory minimum penalty of 2 years;

- Withholding or Destroying a Person’s Identity Documents (for example, a passport) for the purpose of committing or facilitating trafficking of that person—Adult Victim (subsection 279.03(1)): which carries a maximum penalty of five years imprisonment; and,

- Withholding or Destroying a Person’s Identity Documents (for example, a passport) for the purpose of committing or facilitating trafficking of that person—Child Victim (subsection 279.03(2)): which carries a maximum penalty of 10 years imprisonment and a mandatory minimum penalty of 1 year.”[88]

To convict an individual of human trafficking charges, there must be proof of the “act element, which is recruiting, transporting or harbouring someone,” and proof that the act element was “done for the purposes of exploiting the victim, […] or for the purposes of facilitating their exploitation by someone else.”[89]

While legislation has been implemented against trafficking in persons, witnesses noted that human trafficking cases may not result in charges being laid, nor in convictions;[90] some suggested that either penalties are not enforced,[91] or those who do receive penalties, do not receive sufficiently harsh punishments to dissuade the crime.[92] Some of the Committee’s informal meetings during travel mirrored this perspective. Nathalie Levman added that:

It is well established that human trafficking offences can be difficult to prove regardless of how they are framed. As noted in Statistics Canada’s 2020 human trafficking juristat, prosecutors may struggle to secure convictions, including because the trauma to which victims are subjected may create difficulties in recalling the relevant events, resulting in victims being perceived as less credible. Victim support and trauma-informed care, therefore, are critical to both healing and successful prosecutions.[93]

Julia Drydyk agreed that victims may be reluctant to share details about their experiences for various reasons, including the retraumatization that can occur during a court process.[94] During travel, the Committee heard that victims and survivors can be highly traumatized and may face intersecting oppressions; these realities can impede individuals’ access to services and justice. Various organizations the Committee visited described their efforts to provide low-barrier access to a continuum of services, either housed within the organization itself, or through a network of community partners. For example, during the Committee’s travel, Peel Regional Police Services told Committee members that in the region, a continuum of services for human trafficking victims and survivors are provided in one centralized location, which facilitates access to these services for victims and survivors.

Lucie Léonard agreed that human trafficking in Canada is difficult to prosecute, and as a result of this, “some police services, under the advice of the Crown, may recommend or lay other types of charges to move the cases through the justice system.”[95] While the purpose of laying charges that are unrelated to trafficking is to hold perpetrators of trafficking accountable in some way, this practice may have an effect on human trafficking-related data collection.[96]

While Nathalie Levman explained that justice officials “regularly train law enforcement on the legislative framework…. [as well as] victim vulnerability,” some witnesses called for increased training for those involved in the judicial process on the ways in which victims may be affected by their experiences.[97] During its travel, the Committee heard from select police services, such as the Peel Regional Police, about the community organization partnerships and networks they rely on to provide safe and trauma-informed services to victims.

Systems of Oppression and Human Trafficking

Human trafficking and sexual exploitation are part of a “continuum of intersecting oppressions such as poverty, homelessness, sexism, racism, the ongoing legacy of colonization, lack of access to work and education, food insecurity, dependency on chemical substances, intimate partner violence, child abuse and neglect, and pornography.”[98] Systems of oppression and discrimination can put some groups of people at higher risk of experiencing human trafficking or exploitation within the sex industry. The following sections describe some of those systems.

Witnesses noted that anti-trafficking policies must consider systemic oppression and discrimination as well as social and economic inequalities, and not only individual vulnerabilities, to fully address human trafficking.[99] Prevention initiatives are discussed in another section of this report.

Sexism and Discrimination Based on Gender Identity and Sexuality

Witnesses noted that structural violence and oppression against women as well as sexual inequality, make women more vulnerable to experiencing exploitation, including in the sex industry.[100] The Committee was told that the demand for sex, and for access to women’s and girls’ bodies, “fuels and supports” exploitation.[101] This demand is easily met because of the wide distribution of sexually exploitative or coerced material for profit on online platforms.[102]

As discussed in a previous section, most survivors of human trafficking are women, girls and gender diverse individuals. However, in a written brief, Crime Stoppers noted it is important to remember that most victims do not report the violence they experienced. The organization stated that “[i]n marginalized communities, where there are fewer complaints and reports and fewer resources to help men in difficulty, male victims of sexual exploitation are almost absent from census statistics, but they are indeed there on the ground.”[103]

Colonialism

Historical and modern forms of colonialism have ongoing negative impacts on the safety and security of Indigenous women, girls and gender diverse individuals in Canada. Melanie Omeniho, President of Women of the Métis Nation - Les Femmes Michif Otipemisiwak, told the Committee that Indigenous women:

[H]ave always been specifically targeted for violence through federal policies and legislation, such as strict policies, marriage laws and the rights to property that were created to undermine family, community and the political structures that existed within [Indigenous] communities.[104]

The impacts of colonialism, which include loss of culture and identity, the hyper sexualization of Indigenous women and girls, high rates of poverty, the over-representation of Indigenous youth in foster care, intergenerational trauma and experiencing abuse and mental health issues, make Indigenous women, girls and gender diverse individuals vulnerable to exploitation.[105] Violence against Indigenous women, girls and gender diverse individuals is “so normalized that people don't realize that when these young people are being sexualized through the Internet, they become victims and fall prey to people who are trying to exploit them.”[106] Further, high rates of violence against Indigenous women, girls and gender diverse individuals also make them more likely to live with a disability, including invisible disabilities like traumatic brain injuries.[107]

The systems of oppression and discrimination described in other sections of this report also make Indigenous women, girls and gender diverse individuals who live in poverty more likely to rely on sex work to generate income and support themselves.[108] In turn, this makes them more vulnerable to over-policing[109] and of being labelled as trafficking victims which negates “the agency of Indigenous women who sell sexual services and … deflects from recognizing the numerous ways a colonial state reproduces violence, injustices and other harms.”[110]

To eliminate the exploitation of Indigenous women, girls and gender diverse individuals, the social and economic inequalities they experience must be addressed, including ensuring their income security, such as through Call for Justice 4.5, a guaranteed annual liveable income, access to healthcare and to social and cultural supports.[111]

Racism

Racialized individuals in Canada do not access the same economic opportunities as non‑racialized individuals, which leads to higher rates of poverty and poor educational and health outcomes within racialized communities.[112] Those inequalities may contribute to their decision to enter sex work and their vulnerability to exploitation and human trafficking. During its visit in Halifax, the Committee met with Katrina Jarvis, a representative from the Association of Black Social Workers. She shared the findings of the report entitled Hearing Them: Voices and Lived Experiences from the Sex Industry in Nova Scotia. This report notes that the decision to enter sex work and the social and economic circumstances within which African Nova Scotian and Black Nova Scotians make that choice include “a history of slavery and anti-Black racism” in Canada.[113]

As well, the Committee was told that racialized individuals involved in the sex industry could be subjected to profiling from law enforcement officers. In a written brief, Sandra Ka Hon Chu and Robyn Maynard said: “Black women are often assumed to be involved in sex work merely for walking in public spaces due to sexualized stereotypes about them, and Indigenous and Black sex workers have themselves been accused of human trafficking when they work collectively.”[114]

Ableism

Women, girls and gender diverse individuals with disabilities “are particularly vulnerable to childhood sexual violence, gender-based violence, and human trafficking.”[115] They experience sexual violence “repetitively and frequently because of the precise fact that [they are] disabled.”[116] This increased vulnerability to violence, including human trafficking, is rooted in ableism and other forms of oppression and discrimination that women, girls and gender diverse individuals with disabilities face throughout their lives, including:

[C]ommunications barriers, increased likelihood to live in poverty, lack of inclusive and affirming sexual education or access to sexual health services, reliance on or control of caregivers, stereotypes labelling them as not sexual or hypersexual, barriers with the criminal justice system, and not being believed when reporting abuse.[117]

In a written brief, the DisAbled Women's Network of Canada stated that these patterns of exploitation should be addressed in anti-trafficking policies.[118] More precisely, the DisAbled Women's Network of Canada recommended that policies need to “[a]ddress the systemic barriers that make women and girls with disabilities and other groups more vulnerable to trafficking: isolation, social exclusion and discrimination, low income and poverty, housing precarity, inadequate access support services.”[119]

Social and Economic Inequalities

Sexual exploitation results from “existing social and economic inequalities that affect women in particular.”[120] For many women, girls and gender diverse individuals, these social and economic inequalities oftentimes result from oppression or discrimination, and/or from personal life experiences. Several factors and life experiences can make people more vulnerable to human trafficking, including:

- experiencing poverty, isolation and lack of family support;[121]

- being a survivor of abuse in childhood;[122]

- struggling to secure affordable housing or being homeless, and facing barriers because of a disability, language skills;[123] and

- mental health issues or trauma, including traumatic brain injuries.[124]

Kyla Clark, Program Coordinator at Creating Opportunities and Resources Against the Trafficking of Humans, referred to these as “invisible identities.”[125]

Many witnesses explained that traffickers are exploiting vulnerable individuals who are socially isolated or do not have their basic needs met, such as financial and housing needs.[126] As well, the Committee was told that poverty can be both a factor for entry into the sex industry and a barrier to exiting it.[127] Sandra Wesley noted:

In our communities, we often see [lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender] youth who've been expelled from their families, particularly young gay men who find themselves on the street and who have no choice, in order to survive, but to find someone who will pay the rent, someone with whom they will have sex. For many of these young people, the central problem in their lives is not the exchange of sexual services. They will be very vulnerable to abusers who will take advantage of the situation. Ultimately, it's because they don't have a place in society. They have nowhere to live. They don't trust the child welfare system. They have to hide from the police. That's where most of this violence comes from.[128]

In addition, witnesses noted that traffickers often use drugs to keep victims dependent and exploitable:

That method is used to try to alter victims' judgment so they are simply desensitized, until they become mere commodities in the sex trade. The organizers and traffickers want their prey to be fragile. When they are using, they are easy to control. Drug trafficking is therefore directly associated with human trafficking, as shown in the percentage of reports received.[129]

Individuals who are being exploited can also start using drugs to cope with their situations.[130] Furthermore, drugs were presented as “the most effective way to keep [victims of sexual exploitation] in servitude”[131] because “when they are using, they are easy to control.”[132] It was also noted that “[t]he shorter the period of time a victim is in the situation and the sooner they are recognized, the sooner they’ll be pulled out of the situations and can rehabilitate their life and find their way back to society.”[133]

Additionally, Ieesha Sankar, Director, Program and Services, at Ka Ni Kanichihk Inc., explained that people who are homeless and involved in sex work might fear reporting violence they experienced because the person committing violence against them might also be the person fulfilling their basic needs.[134] Lack of affordable housing is also a situation that leads to exploitation.[135] Monica Abdelkader, Director, Resettlement and Settlement Services, Association for New Canadians, explained that many individuals who seek the help of her organization “are at heightened risk for trafficking or become victims of trafficking because they end up turning to people who offer what seems like genuine help to get them out of this abject poverty.”[136]

The Committee was told that the digital space has changed the profile of individuals vulnerable to human trafficking. Tiana Sharifi, Chief Executive Officer of Exploitation Education Institute, explained that “[w]hen online, youth seek to meet their higher[-]level needs, such as belonging, self-esteem and self-actualization.”[137] Witnesses noted that youth are seeking connection and interaction online,[138] but many girls who thought that the person they were connecting with was a friend were instead being groomed and/or recruited.[139] As well, the abundance of hypersexualized and objectification content on social media platforms normalizes self-exploitation which can lead to youth being groomed into exploitation and trafficking.[140]

Other Systemic Challenges

Over the course of this study, witnesses highlighted other systemic issues related to human trafficking and sexual exploitation, notably those affecting migrant workers and individuals involved in the sex industry. The sections below describe these issues.

Challenges Facing Individuals Involved in the Sex Industry

The Committee heard that anti-trafficking policies and initiatives could push sex work underground,[141] which results in dangerous working conditions in the sex industry.[142] For instance, sex workers can be profiled and criminalized by law enforcement officers, particularly racialized, Indigenous and migrant sex workers, as officers attempt to locate trafficking victims.[143] Witnesses noted that approaches called “raid and rescue” or “rescue” operations are harming sex workers.[144] For example, in a written brief, Maggie's: Toronto Sex Workers Action Project stated:

Many anti-trafficking initiatives result in increased police presence in our workplaces, surveillance, interrogation, harassment, detention and deportation. Under the guise of “protection” antitrafficking policies often further criminalize our communities, endanger our lives, impose deadly working conditions, strip us of our agency, perpetuate systemic violence and harmful stereotypes onto the most marginalized of sex workers that have real-world implications for our communities.[145]

The conflation of sex workers and trafficking victims by law enforcement results in sex workers working in isolation and without social supports; this can lead to increased vulnerability to experiences of violence and discrimination.[146] Excessive policing within the sex industry also deters sex workers from reporting violence they experience.[147] For this reason, witnesses recommended decriminalizing sex work to improve safety within the industry and reduce sex workers’ vulnerability to exploitation.[148] Sandra Wesley explained:

When you're in a criminalized industry, where everyone has to protect themselves from the police, where the driver, the receptionist, the client can all go to jail, it gives abusers the opportunity to be violent or take advantage of people. That's why it's impossible to separate human trafficking concerns from the decriminalization of sex work.[149]

Challenges Facing Migrant Workers

The Committee heard that there are systemic issues affecting migrant workers’ vulnerability to human trafficking and to exploitation within the sex industry. Jovana Blagovcanin, Manager, Anti-Human Trafficking, at the FCJ Refugee Centre, noted that migrant women “are highly vulnerable to exploitation due to their gender, precarious immigration status, language barriers and limited knowledge of their rights or available resources, which in turn results in limited access to their rights.”[150] Monica Abdelkader explained that data from a recent project showed that migrant workers’ vulnerability to trafficking was higher the remoter or more rural the communities they were settling in.[151]

The Committee was told that oftentimes exploitation of migrant workers in Canada starts after the person travels to Canada[152] and is gradual, going from poor working conditions to labour and/or sexual trafficking.[153] Julia Drydyk explained that the “vast majority of individuals who experience trafficking where the [Canada Border Services Agency] is involved are those migrant workers who are coming into Canada through temporary foreign worker permits and are largely experiencing labour trafficking in our agricultural and manufacturing sectors.”[154] During its visit in Vancouver, the Committee met with representatives of Migrant Workers Centre in Vancouver who explained that labour trafficking intersects with sex trafficking, as employers might force migrant workers to perform sex services as part of their employment, a situation they described as being increasingly common.[155]

Temporary Resident Permits for Victims of Trafficking in Persons in Canada

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada is responsible for “helping protect out-of-status foreign national victims of trafficking.”[156] Representatives from the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) told the Committee that there are services available to migrant workers who find themselves in situations of exploitation or who are being trafficked, such as emergency housing and funding as well as support services to regularize their status in Canada.[157] For example, victims of trafficking in persons in Canada can be issued temporary resident permits (VTIP TRP), which initially allows them to secure temporary resident status for a period of six months (a subsequent or longer-term VTIP TRP can be issued for up to three years).[158] A VTIP TRP also provides survivors access to health care, including mental health care, under the interim federal health program and allows them to apply for an open work permit.

Witnesses noted several issues with the VTIP TRP process. Firstly, the Committee was told that the number of VTIP TRP issued is low:[159] 155 VTIP TRPs were issued in 2022.[160] In a written brief, the organization Migrant Workers Alliance for Change said that most VTIP TRP applications are refused “because the definition of trafficking for the purposes of accessing temporary resident permits is specific and limited, despite the expansion of discourse and funding on the concept of trafficking.”[161] The Committee also heard that VTIP TRPs are not always renewed, which forces workers to leave Canada or to stay but become undocumented.[162]

In a written brief, the organization Legal Assistance of Windsor and Sisters of St. Joseph of Toronto explained that the VTIP TRP “is limited in scope and has an uncertain outcome due to the discretionary process. Outdated criteria and understanding of exploitation by [Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada] officers reduce migrant experiences to individual culpability often blaming them for their own demise.”[163]

While survivors are technically not required to testify against their trafficker to be granted a VTIP TRP,[164] Jovana Blagovcanin noted that VTIP TRP applications are being denied because there are no pending investigations or cases in court. In this situation, survivors of trafficking have “very few options to safely remain in Canada.”[165] As well, witnesses mentioned that some services and supports might not be available to individuals who are residing in Canada under a VTIP TRP, such as housing supports or family reunification.[166] Finally, the pathway from a VTIP TRP to a permanent residency is challenging as it can take years of being legally in Canada under a VTIP TRP before being eligible for permanent residency.[167] Witnesses recommended making this process quicker and more accessible to survivors.[168]

Migrant Workers in the Sex Industry

Migrant workers involved in the sex industry face specific structural violence because of “[r]estrictive immigration policies preventing them from legally engaging in sex [work] and related industries.”[169] The Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (IRPR) prevent migrant workers from working in sex industry-related employment,[170] namely for employers and workplaces that offer striptease, erotic dance, escort services or erotic massages.[171] If involved in such activities, migrant workers would be at risk of being criminalized, deported, and barred from Canada, even if they do not face criminal charges themselves.[172]

As described in a previous section, sex workers can be profiled and criminalized by law enforcement officers, as officers attempt to locate trafficking victims.[173] Migrant women involved in sex work are regularly assumed to be trafficked, a view “often based on racist understandings, particularly of Asian women, who are believed to be naïve and duped into doing sex work.”[174] Because of this assumption, police services and the Canada Border Services Agency target workplaces where migrant workers and racialized individuals are present, as part of their anti-trafficking initiatives.[175]

This criminalization of migrant workers involved in sex work push them not to report the violence they experience or not to access services “to avoid invasive and potentially harmful questions and disclosures.”[176] Angela Wu stated:

When they choose to work in the sex industry, they automatically are placed at risk of arrest, detention and deportation. We have actually seen that happen several times with the women we support. Often they come to the attention of the police because they have decided that they want to report violence or exploitation. Unfortunately, almost every single time we have seen the women actually end up getting deported.[177]

The Committee was told that efforts to protect migrant sex workers from exploitation that only focus on the role of traffickers “absolves the government of addressing systemic causes of human trafficking among im/migrant sex workers.”[178] To protect migrant workers against exploitation, witnesses recommended the Government of Canada repeal regulations that prohibits migrant workers from engaging in sex work.[179] In particular, witnesses recommended repealing sections 183(1)(b.1), 185(b), 196.1(a), 200(3)(g.1) and 203(2)(a) from the IRPR.[180]

Impacts of Closed Work Permits

Closed work permits tie migrant workers to a specific employer, which puts workers at risk of experiencing exploitation and limits their ability to seek help once they are in Canada and have started working.[181] Maria Mourani, Criminologist, PhD in Sociology and President of Mourani-Criminologie, shared this example with the Committee:

[Closed work permits] are issued to young women from abroad who are supposedly required to work in places like Montreal's posh restaurants, but who end up working unwillingly in the sex trade. The so‑called employers, who are really pimps disguised as restaurant owners, use these permits to keep women on a tight leash. The women don't dare to report them, because they're afraid of being sent back to their home country.[182]

Migrant workers are vulnerable to exploitation because their “employers know that they are breaking the terms of their [closed] work permits” and employers can “use this knowledge to underpay workers, force them to work longer hours, and in more hazardous conditions.”[183]

For this reason, witnesses recommended abolishing employer-specific work permits in favour of open work permits.[184] Representatives of Migrant Workers Centre suggested sector-based permits as an alternative to closed work permits.[185] Witnesses also recommended the Government of Canada issue permanent residency to migrant workers to combat possible exploitation.[186] In a written brief, the Yukon Status of Women Council noted that permanent residency would give “im/migrant sex workers … increased access to legal recourse, support services and protections if needed.”[187]

Challenges Facing International Students

International students can also be vulnerable to exploitation[188] in part, “because of their financial situations, living conditions, lack of affordable housing… Language barriers are another thing.”[189] For example, they can become dependent on landlords or employers if they have no other way to generate income than to comply with what their employer asks them to do.[190] Combined with “the compounding issues of racism, colonialism and sexism,”[191] these risk factors mean that “[international students] become easy targets of these traffickers.”[192] Often, international students may hesitate or feel unsafe to report their situation and seek support, “because of their [immigration] status and because they don’t know how to navigate the system.”[193] Kathleen Douglass, President Elect and Advocacy Chair at the Zonta Club of Brampton-Caledon, stressed the importance for international students to receive the information, upon arriving to Canada, needed to understand “that they have rights and do not have to be trafficked because they have to pay back loans and are obligated to provide for their families.”[194]

Therefore, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 5

That the Government of Canada support organizations that work with youth involved in the child welfare and foster care system, including Indigenous youth, to ensure that they receive culturally appropriate and trauma-informed services that meet their needs and reduce their vulnerability to becoming victims of human trafficking.

Recommendation 6

That the Government of Canada implement a Red Dress Alert for missing Indigenous women, girls and Two-Spirit people.

Recommendation 7

That the Government of Canada, respecting the jurisdiction of provinces and territories, and in collaboration with Indigenous peoples, support the development of awareness campaigns and resources in diverse languages for international post-secondary students related to preventing, and reducing the risk of experiencing, human trafficking, including human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation.

Recommendation 8

That the Government of Canada, in collaboration with provinces and territories, implement measures to further protect migrant workers with an irregular immigration status from human trafficking and exploitation, and from abuse in difficult workplaces where they may be subject to blackmail, threats, coercion and violence from employers if they leave or report this abuse, jeopardizing their work permits and opening themselves up to deportation to their home country, and consider measures such as:

- accelerating and simplifying the process of obtaining permanent residence status from a temporary resident permit for a victim of trafficking in persons;

- studying potential repeal or amendment of regulations in the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations that criminalize migrant workers engaging in sex work; and

- continuing to implement open- or sector-based work permits instead of employer-specific work permits.

Recommendation 9

That the Government of Canada, respecting the jurisdictions of, and in collaboration with, the provinces, territories and Indigenous peoples, consider measures that can reduce poverty and ensure that individuals’ basic needs are met, including:

- implementing a guaranteed annual liveable income or other financial support models, making sure to minimize barriers to these supports for low income households;

- supporting the provision of safe, affordable and accessible housing, including emergency shelters, safe houses and transitional housing, for all; and

- continuing to invest in long-term funding for organizations providing culturally appropriate and trauma-informed gender-based violence programs and services.

Improving Services for Survivors of Human Trafficking in Canada

“Our women, girls and gender diverse people deserve more than a common shelter bed where they wonder if the person next to them is coming to retrieve them for their trafficker. They deserve more than 20 counselling sessions. After all the atrocities and abuses that they've endured, they shouldn't have to give up their pets. These may seem like small, trivial things to those who have stability in their lives, but to the person who is finally able to exit human trafficking, those are the things that can help a person move into rehabilitation from the most heinous life instead of returning to it, which they often feel is their only option, due to the guilt and shame from the abuses they have suffered.”

FEWO, Evidence, 4 May 2023, 1535, (Tiffany Pyoli York, Anti-Human Trafficking Coordinator and Public Educator, Sudbury and Area Victim Services).

Survivors of human trafficking oftentimes “have become completely dependent upon the traffickers for food, money and companionship.”[195] For this reason, they often require access to a variety of specialized supports and services to successfully exit situations of exploitation, such as housing, mental health services and training and educational programs.[196] During its travel, the Committee heard that victims and survivors of trafficking face significant barriers in accessing transitional housing after they leave emergency or short-term shelter services. The lack of availability of transitional housing and related supports may contribute to victims and survivors remaining vulnerable to further exploitation and trafficking. Raman Hansra, Project Director, Family Services, at Indus Community Services, noted that a “trauma-informed approach and culturally and linguistically appropriate services are the key to supporting these survivors or victims.”[197] Without these, survivors are at risk of experiencing exploitation again.

During this study, the Committee met with and visited many organizations providing frontline and direct support to survivors of trafficking. Some were invited to appear at Committee meetings in Ottawa, and some shared information with the Committee during its travel to Vancouver, the Region of Peel, Sault-Sainte-Marie, and Halifax. An overview of the different service providers the Committee met with during its travel in the Spring of 2023 is available in Appendix A.

Despite community organizations across Canada offering a wide variety of services and programs, survivors of human trafficking do not have access to the full continuum of supports and services they require.[198] Witnesses mentioned, for instance, the lack of financial support, educational and training support, mental health services, and legal support for survivors, as well as the lack of adequate funding for these services.[199] Jody Miller, Managing Director of EFRY Hope and Help for Women, told the Committee that all levels of government and community organizations need to work collaboratively to offer the continuum of services needed.[200] The Committee was told that women wanting to leave sex work, or who have been engaged in sex work in the past, also need access to similar services.[201]

During its meeting with a representative of Downtown Eastside Women’s Centre, the Committee heard that the organization utilizes a low-barrier approach to providing services to its clients. The representative noted this approach means that women do not have to disclose information about their situation to access their services; being asked for information is a barrier to access services.

In particular, several witnesses told the Committee about the importance of providing housing options to survivors for them to exit their situations of exploitation successfully. The following section focusses on this issue.

Housing Services

The Committee was told that having access to safe and affordable housing was essential for survivors of human trafficking to be able to exit their situations enduringly.[202] For instance, a representative from the Canadian Human Trafficking Hotline told the Committee that “housing is the number one biggest need that's requested for a referral service through the hotline.”[203] However, accessing housing is a major barrier for survivors.[204] Emergency housing might be difficult to access as shelters are often full or because human trafficking survivors do not meet shelters’ mandates, policies or requirements, in which case survivors of human trafficking might go to a low-barrier shelter that does not provide the services they need.[205] There are also long waitlists for housing, especially for survivors who might need more specialized services or who are older.[206]

Both witnesses who appeared in meetings held in Ottawa and witnesses the Committee met during its travel, noted that a full continuum of long-term housing supports is needed to address human trafficking, such as rent geared to income, portable housing benefits and rent supplements.[207] In particular, Jody Miller recommended that a dedicated housing strategy “that addresses access to immediate beds, as well as independent housing and support services within housing for trauma, mental health and addiction” be developed.[208]

Funding Services for Survivors

“More funding needs to go directly to survivor support and the understanding of the nature of the survivor and the layers that are incorporated into the healing of that survivor.”

FEWO, Evidence, 4 May 2023, 1625, (Melissa Marchand, Member, Zonta Advocacy Committee, Zonta Club of Brampton-Caledon).

To improve supports and services offered to survivors of human trafficking, witnesses indicated that additional funding should be provided to organizations offering such services. In particular, witnesses noted that funding should be provided to “peer-type projects and peer agencies”[209] and to groups directly supporting survivors of violence.[210] Timea Nagy, Chief Executive Officer and Founder of Timea's Cause Inc., noted:

We survivors are also asked to lend our voices and expertise to build programs and policies, only to find out that our suggestions are constantly cut out. Programs, safe houses and services are getting kick-started and funded that we don't actually need or that we as survivors don't actually benefit from.[211]

Another issue highlighted by witnesses was the impact of the current project-based funding model; under this funding model, organizations only receive funding for a limited time, usually a few years, and for a specific project. This means that organizations sometimes are not able to keep offering supports and services if their funding is not renewed.[212] Witnesses called for the Government of Canada to provide operational funding to organizations offering services to survivors of human trafficking.[213] Jody Miller explained:

I feel that being able to have sustainable long-term funding in communities is essential as well, so that we don't have to rebuild these supports that we've put in place and we don't have to start over, and so that we can also provide our staff, who have been trained in providing these models and who are primarily female, with stable employment in providing these services.[214]

Specifically, Coralee McGuire-Cyrette, Executive Director of the Ontario Native Women's Association, explained that current funding models do not work for Indigenous women’s organizations. She stated: “We need that core sustainable funding for [I]ndigenous women's agencies. That hasn't happened here in Canada, and there has to be that long-term, sustainable funding to support [I]ndigenous women's safety.”[215] Fay Blaney, Lead Matriarch at the Aboriginal Women's Action Network, explained that by resourcing programs and services by and for Indigenous women, Indigenous women “would not be subjected to the systemic racism [they] experience within the programs and services [they] access.”[216]

The Committee was also told that the Government of Canada should support and provide funding to sex worker-led initiatives, in particular initiatives that support Indigenous-, Black- and migrant-led sex workers groups.[217] In a written brief, the SWAN Vancouver Society explained that “sex work organizations are best positioned to provide comprehensive, non-judgmental, and tailored services,” yet they are under-resourced to prevent and respond to human trafficking.[218]

Also, the Committee was told that sex workers can struggle to access services if they do not identify as victims of human trafficking or agree to exit sex work. However, access to support services can help prevent sex workers becoming victims of exploitation.[219] In a written brief, the Canadian Women’s Foundation noted that there is a “funding disparity between sex worker support programs and anti-trafficking programs in Canada.”[220] Witnesses recommended the Government of Canada shift away from an anti-trafficking funding framework to ensure that projects funded also meet the needs of sex workers.[221]

In a written brief, the Peel Regional Police recommended establishing a national criminal injuries compensation board for victims of gender-based violence, including human trafficking, which could be used “to support on-going medical treatments, trauma counselling and substance use recovery.”[222]

Services for Migrants in Canada

Migrant workers might face additional barriers in seeking help and services, such as language and cultural barriers, uncertainty related to their employment and immigration status and lack of awareness or understanding of Canadians laws. A representative from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada explained that migrant workers:

[A]re sometimes in a particular situation of precarity where they may not have permanent residence status or are living in a difficult set of circumstances. That precarity adds to those complex dimensions of their feeling like they don't necessarily have the agency to come forward.[223]

Some services and supports might also not be available to individuals without legal status or with temporary status in Canada, such as legal aid supports[224] and housing supports.[225] Witnesses stressed the importance of providing migrant workers with trauma-informed and victim-centered services as well as information about their rights and the various forms of exploitation.[226]

Therefore, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 10

That the Government of Canada, in collaboration with provinces and territories, Indigenous peoples, law enforcement agencies, and community organizations, continue investing in victim support services, including trauma-informed and culturally sensitive counselling, legal assistance, and safe housing options for survivors of human trafficking.

Recommendation 11

That the Government of Canada, respecting the jurisdictions of, and in collaboration with, the provinces, territories and Indigenous peoples, provide funding to diverse organizations and initiatives that support individuals, such as Indigenous, Black and migrant individuals, who are involved in the sex industry, including victims and survivors of human trafficking as well as sex workers, to ensure that they have access to adequate legal, justice, health, mental health and addictions services.

Preventing Human Trafficking in Canada

The Committee heard about the importance of prevention in addressing human trafficking in Canada; witnesses provided various pathways towards the prevention of the crime in Canada. The discussions included: ways to reduce the demand for sexual services; improved education and awareness; a national strategy; initiatives involving police and law enforcement; amendments to existing legislation, including strengthening penalties for traffickers, as well as the decriminalization of sex work; and the implementation of select social policies and programs.

Witnesses told the Committee that addressing the demand for sexual services has a significant role to play in preventing human trafficking in Canada. Many witnesses indicated that doing so would require stricter penalties for individuals who purchase sexual services and/or a greater enforcement of Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act (PCEPA).[227] Diane Matte, the Co-Founder of the Concertation des luttes contre l’exploitation sexuelle, added that Canada’s current anti-trafficking approach does not address the demand for sexual services, which is a “root cause” of trafficking.[228] S/Sgt Robert Christmas, who appeared as an individual, suggested further research related to the ways in which a combination of enforcement and education may affect the demand.[229]

To prevent human trafficking in Canada, many witnesses spoke about the importance of education in schools and for youth.[230] The Committee heard that students should be taught in culturally relevant, age appropriate and safe ways about healthy relationships, consent, online safety, identifying exploitation and human trafficking and the supports and resources available.[231] Witnesses added that youth often respond well to peer-to-peer education, or other formats and language that are relevant for different age groups, and that these considerations should be acknowledged in the provision of education.[232]

A Federal Approach to Combatting Human Trafficking in Canada

A National Strategy Combatting Human Trafficking in Canada

Witnesses called for a national approach to combat and prevent human trafficking in Canada that places victims and survivors at its centre, and addresses structural and systemic barriers.[233] Julia Drydyk, and other witnesses,[234] emphasized that there should be a holistic and “whole-of-Canada” approach to ensure that provinces and territories are “acting similarly and in line.”[235] In written submissions, organizations noted that a national strategy should be sufficiently funded, and that the strategy should be permanent to avoid a disruption in funding during strategy and funding cycle transition periods.[236]

Public Safety Canada is the federal department responsible for the National Strategy to Combat Human Trafficking (the Strategy), which was launched in 2019. Department representatives told the Committee that this Strategy brings together federal efforts across departments under one framework and is based on several pillars: prevention, protection, prosecution, partnership and empowerment. Between 2018 and 2024, $75 million in funding was allocated to the Strategy, including a $14.5 million investment for the Canadian Human Trafficking Hotline. The Strategy is “in its last year” and while achievements have been made, department representatives noted that “there is much more to do.”[237] Crystal Garett-Baird, the Director General, Gender-Based Violence at the Department for Women and Gender Equality, added that the National Action Plan to End Gender-Based Violence “helps federal, provincial, and territorial governments to build on existing initiatives and continues to work with victims and survivors, Indigenous partners,” and other relevant service providers and experts to prevent and address gender-based violence, including human trafficking.[238]

Some organizations explained that policies that are meant to combat trafficking, particularly sex trafficking, may lead to the sex industry being unfairly targeted by police.[239] This targeting may lead sex workers to evade detection by police, increasing these individuals’ vulnerability to violence, isolation and marginalization.[240] According to several organizations, as there is an over-representation of Indigenous and racialized individuals working in the sex industry, the over-surveillance and policing of the sex industry may disproportionately affect these individuals.[241] The Yukon Status of Women Council wrote in its submitted brief, that:

Anti-trafficking policies enable over-surveillance of sex workers, especially racialized or otherwise marginalized workers, and push sex workers further underground, where exploitative conditions can thrive more easily… Further harm is experienced by Indigenous sex workers, when they are mislabeled as trafficking victims, as it not only disregards their autonomy, but also reinforces racist and colonial narratives, without addressing or acknowledging the impacts of colonization. Essentially, in the place of addressing root causes of trafficking, anti-trafficking policies create better conditions for exploitation to grow - and do nothing to support people who have experienced trafficking or exploitation.

Finally, witnesses cautioned that some anti-trafficking policies and the language used in these policies may harm individuals who have experienced sex trafficking.[243] Kate Price explained that the language used to describe experiences of human trafficking, particularly in the media, may be so sensationalized and informed by stereotypes of “bars on windows,” that victims do not feel that their experience is valid or reflected. As a result, they may not report the crime nor seek support.[244]

Some witnesses called for recognition that anti-trafficking policies should not be anti-sex work,[245] as well as for the inclusion of sex workers and individuals with experience in the sex industry in the development and implementation of policies that are meant to reduce exploitation and violence—including human trafficking—in the sex industry.[246] Krystal Snider, the Lead Project Consultant at the Women’s Centre for Social Justice agreed that: “you can support the work to end human trafficking while also protecting the rights of those who are engaged in the sex industry by choice.”[247]

Human Trafficking Education, Training and Awareness

Under the Strategy’s Prevention pillar, the awareness campaign “It’s not what it seems” was launched to educate the public, in particular youth and parents, about human trafficking. Educational materials for Indigenous-specific audiences are under development.[248] Witnesses spoke about public awareness campaigns, which can be helpful tools in prevention. The Committee heard that awareness campaigns on human trafficking should include information on gender equality and respect for women and girls, identifying human trafficking, the realities of sexual exploitation and human trafficking in Canada.[249] Bonnie Brayton, Chief Executive Officer of the DisAbled Women’s Network of Canada, added that public education on human trafficking responsiveness must centre disability, as “many survivors become disabled because of trafficking, and their disability makes them targets for being trafficked.”[250]