FOPO Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Protection and Coexistence of the North Atlantic Right Whale in Canada

Introduction

Between 27 September 2022 and 1 November 2022, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans (the Committee) undertook a study to examine the fishery management measures put in place to protect North Atlantic right whales (NARW). This study sought to evaluate the impact these measures have had on the reduction of NARW injury or deaths in Atlantic Canada and Quebec as well as the impact these measures have had on the economies of coastal communities. It also sought to provide the government with options and recommendations on how to improve these measures.[1] The Committee heard from 32 witnesses over the course of six meetings.[2]

North Atlantic Right Whales

The NARW was listed as “Endangered” under the Species at Risk Act (SARA) in 2005. The NARW population has been declining since 2010 due to increased mortality and a decrease in the reproductive rate.[3] The most recent species estimates suggest there were between 333 and 347 individuals in 2021, down from the 2020 species estimate of between 343 and 352 individuals.[4] Lyne Morissette, Marine Biologist and Environmental Mediator at M-Expertise Marine, described the NARW’s situation as critical, stating that this species of whale could be extinct in 20 years if nothing is done to protect it.[5]

According to the species description in the Species at risk public registry, the NARW is:

[A] migratory species. It lives in coastal and shelf waters along the eastern seaboard of North America, from Florida to Newfoundland and Labrador. […] The species is detected year-round in Canadian waters, but detections are less numerous during the winter. The distribution of [NARW] in Canadian waters is primarily determined by the availability of their prey, copepods of the genus Calanus (small, shrimp-like animals).

[…]

Since 2010, the distribution of [NARW] in Canadian waters has shifted, and they are using previously predictable habitat areas, such as the Bay of Fundy, less frequently. Large groups of [NARW] have been observed in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence since 2015.[6]

Historically, commercial whalers targeted NARWs, which depleted the species. While the cause of death could not be determined for most NARW found dead in Canadian waters since 2017, when it could be determined following a necropsy, the leading causes of death were entanglements in fishing gear and vessel strikes.[7] The Species at risk public registry notes that:

The main threats to the North Atlantic Right Whale are entanglements in fishing gear and vessel strikes. These are the leading causes of death in individuals that have been examined. Other threats include: habitat loss and degradation (for example, through vessel presence and acoustic disturbance), infectious diseases, contaminants, marine biotoxins, disturbance from tourism, and shifts in the abundance and distribution of prey due to climate-driven and other environmental changes in the ocean.[8]

The recovery strategy for NARW under SARA states the following interim recovery goal: “To achieve an increasing trend in population abundance over three generations.”[9] Since the generation time for NARW is approximately 20 years, at least 60 years will be needed to meet the interim recovery target.

In 2017, the distribution of NARW changed dramatically and their habitat shifted towards the Gulf of St. Lawrence, an area with some of Canada's most lucrative and productive fisheries, as well as important shipping lanes.[10] That same year, 12 NARWs were found dead in Canadian waters and five NARWs were found dead in American waters. This led the United States (U.S.) National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to declare an “unusual mortality event.”[11] In 2019, nine more NARWs were found dead in Canadian waters, and one was found in American waters. It can be difficult to determine the cause of death for NARWs because of decomposition or difficulties accessing carcasses. Figure 1 shows the cause of death of NARWs found in Canadian and American waters between 2017 and 2021.

Figure 1—Cause of Death of North Atlantic Right Whales Found in Canadian and American Waters Between 2017 and 2021

Source: Figure prepared by the Committee based on data obtained from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), 2017–2022 North Atlantic Right Whale Unusual Mortality Event; and NOAA, North Atlantic Right Whale Causes of Death for Confirmed Carcasses.

The Effects of Fishing Gear Entanglements on North Atlantic Right Whales

NARWs can be struck by vessels or be entangled in fishing gear on more than one occasion throughout their lives. NARWs are large enough to drag gear when they are entangled. Many appear to shed the gear or self-disentangle. Sean Brillant, Senior Conservation Biologist, Marine Programs with the Canadian Wildlife Federation, explained that more than “85% of the individuals of this population have scars indicating they’ve been entangled at least once in their lifetime, and some as many as seven times. Every year, a quarter of the population has new scars.”[12] If NARWs cannot shed gear by themselves or disentanglement efforts by human intervenors are impossible or unsuccessful, NARWs can remain entangled for long periods of time, even years.

While entangled, a NARW needs more energy to swim and feed to overcome the increased drag caused by the gear. Entanglement most often occurs near the head, which can disrupt the baleen[13] and reduce feeding efficiency. Therefore, chronically entangled NARWs are commonly emaciated. The lacerations and infections caused by entanglements can lead to severe tissue and bone damage, and death. The average time for an entangled NARW to die is six months.[14]

It may be difficult to identify the fishery or country from which the fishing gear removed from an entangled NARW originates by the time the gear is found.[15] Brett Gilchrist, Director of National Programs, Fisheries and Harbour Management at Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), emphasized that investigations are necessary when entanglements occur to help determine the origin of the fishing gear. He noted that a particular fishery should only be linked to an entanglement if the “investigation is conclusive”.[16] Mandatory gear marking requirements in Atlantic Canada and Quebec to address these difficulties are discussed in an upcoming section.

Measures to Reduce the Impacts of Human Activities on North Atlantic Right Whales

In the wake of the 2017 unusual mortality event, there has been widespread support to strengthen the protection measures for NARW. Jean Lanteigne, Director General, Fédération régionale acadienne des pêcheurs professionnels, stated that “the presence of [NARW] in the Gulf has been front and centre for all of the stakeholders who are in any way involved in the fishing industry in Atlantic Canada.”[17] Bonnie Morse, Project Manager, Grand Manan Fishermen's Association, stated that fishers “understand that [NARW] and all marine mammals have a place in the ecosystem, and a healthy ecosystem ensures their longevity as much as it does that of the animals that live there.”[18]

Jules Haché, member of the board of directors of the Acadian Peninsula’s Regional Service Commission, highlighted the importance of the fishing industry to communities on the Acadian peninsula, stating that the fishing industry was essential to the economic and cultural fabric of these communities. Out of about 50,000 inhabitants, there were 6,500 fishers and 7,000 more employed in the fisheries processing sector. Jules Haché also reported that the implementation of measures to protect NARW, starting in 2018, has created uncertainty for fishers, and that efforts should now be focused on ensuring the viability of the fishing industry and the job security of those involved in it.[19]

The Government of Canada, through various departments, has committed significant effort to protecting NARW. Adam Burns, Acting Assistant Deputy Minister, Fisheries and Harbour Management, DFO, stated that “Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Transport Canada, Environment and Climate Change Canada and Parks Canada have worked together to make targeted investments to address immediate threats facing [NARW] and other endangered whale species, including $167.4 million under the Whales Initiative announced in Budget 2018.”[20]

Recommendation 1

That Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) engage in greater cross-collaboration with the three other departments that carry out activities connected to marine mammals (Transport Canada, Parks Canada and Environment and Climate Change Canada). This would inspire cross-collaboration between DFO and the fishing industry.

The Government of Canada’s efforts were commended by witnesses. Kimberly Elmslie, Campaign Director for Oceana Canada, stated that, since 2017, “the government has created a world-class science team. DFO is developing cutting-edge technology on ropeless gear for snow crab. DFO scientists are utilizing hydrophone arrays, gliders, infrared cameras, satellite imaging and more. There needs to be continued financial support for all of these programs.”[21]

Recommendation 2

That DFO allocate scientific funds to improve scientific knowledge of North Atlantic Right Whale (NARW) life expectancy, causes of unnatural death, and changing migration patterns caused by climate change to develop fisheries management measures based on the best available science.

Witnesses were impressed at the measures taken by Canadian fishers and the speed at which the measures were implemented.[22] Kimberlie Elmslie stated:

It's phenomenal to me, when I look back to 2017 when we had this crisis year of 17 deaths, just how much happened, and how quickly. These whales were entering a completely new area, which we weren't expecting or predicting. Those fishermen in that area rose to the challenge.[23]

The measures discussed by the witnesses included:

- de-icing small craft harbours to allow fishers to start their season as early as possible and minimize the duration of the overlap between fishing activities and the presence of NARW;

- the closure of fishing areas after NARW detections;

- the modification of fishing gear to reduce the likelihood and severity of NARW entanglements; and

- vessel slowdowns to reduce the number and severity of vessel strikes.

However, many witnesses explained to the Committee that the further refining and tailoring of the protection measures for NARW would be beneficial.

Earlier Start to Fishing Seasons

Adam Burns stated that targeted icebreaking operations happen in the Gulf of St. Lawrence to help fishers get out on the water as early in the spring as possible.[24] Marc Mes, Director General of Fleet and Maritime Services at the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG), explained that CCG ice breakers

operate each winter to make sure that marine traffic moves safely through ice-infested waters. These same ice breakers also facilitate access to open waters in the spring so that fisheries, such as the snow crab fisheries in Quebec and the Gulf regions, can be opened as early as possible while not compromising the life of mariners. The criticality of these ice breakers cannot be understated. The Canadian Coast Guard works extremely closely with all our stakeholders to meet their expectations during the winter period and in the challenging shoulder seasons.[25]

Marc Mes described the prioritization of icebreaking services and the cascading of assets used by the CCG to assign assets to break ice near fishing harbours. When icebreaking resources are available for fishing harbour breakouts, the first ship used is the light icebreaker. In areas where a light icebreaker is unable to enter because of its size and draught,[26] other resources are cascaded in including third-party vessels, such as small tugs, which are contracted by the CCG for use if and when demands exceed CCG capacity, and the Amphibex machine which was described as “an excavator with claws on it that floats on ice.”[27] Marc Mes explained that the last resort is the hovercraft since its use must be balanced with requirements to break ice to avoid flooding on personal properties.[28] Robert Wight, Director General of Vessel Procurement at the CCG, informed the Committee that new mid-shore, multi-mission vessels, capable of breaking 40 centimetre-thick ice and of operating in shallower waters, are expected to be in operation by the end of this decade.[29]

Marc Mes explained that as a result of the cascading of CCG ice-breaking assets over the last few years, fishing harbours have been opened approximately one week earlier, on average, than when the cascading process was not in place.[30] However, Jean Lanteigne explained that fishers waiting to begin harvesting are “at the [CCG]’s mercy” because of its prioritization of tasks.[31] He added that the fishing industry makes every effort to “maximize the number of days during which we can fish before the [NARW] arrive.”[32]

Recommendation 3

That the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) develop and implement a plan to support the earliest feasible opening of fisheries in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence that considers both economic and environmental impacts, where the early opening of such fisheries would reduce the likelihood of interactions between NARWs, fishers, and gear that may cause entanglement and/or injury to NARWs.

Recommendation 4

A plan should consider harbour breakouts, the dredging of the Shippagan and Caraquet channels, where improvements might be made to the resource “cascades” that are used when undertaking multi-stage ice breaking operations, and how the ability to conduct parallel operations might be strengthened.

Recommendation 5

That the CCG provide information on the operational suitability of current marine navigation equipment, and information on how marine navigation systems for the fishing and shipping industry might be modernized and digitized as necessary to ensure the protection of NARW.

Recommendation 6

That, using funds from the Atlantic Fisheries Fund or any other eligible funding program, a suitable vessel be built or an existing vessel be retrofitted as quickly as possible to clear ice from the channels and around the wharves in the Gulf region, especially in Caraquet Bay and Shippagan Bay, which will allow the fishing season to open earlier.

Recommendation 7

That DFO continue icebreaking operations using all the ships and equipment necessary to allow the season to open early and that contracts with third parties be in place by the end of January at the latest, preceding the start of the fishing season.

While Jean Lanteigne believed fishing seasons should be opened as early as possible to minimize the period of time fishing activities overlap with the presence of NARW in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, he cautioned that fixing a date for the opening of the fishing season could be dangerous because of the uncertainty surrounding environmental conditions on any particular date. He preferred the current approach, which involves a committee on fishery season openings which “includes all fishery stakeholders, such as the DFO, the [CCG] and Environment Canada.”[33]

Recommendation 8

That the snow crab fishing season in the Gulf of St. Lawrence open at the same time for all fleets and provinces in accordance with the protocol of the Committee for setting the opening date for the fishery.

Fishing Area Closures

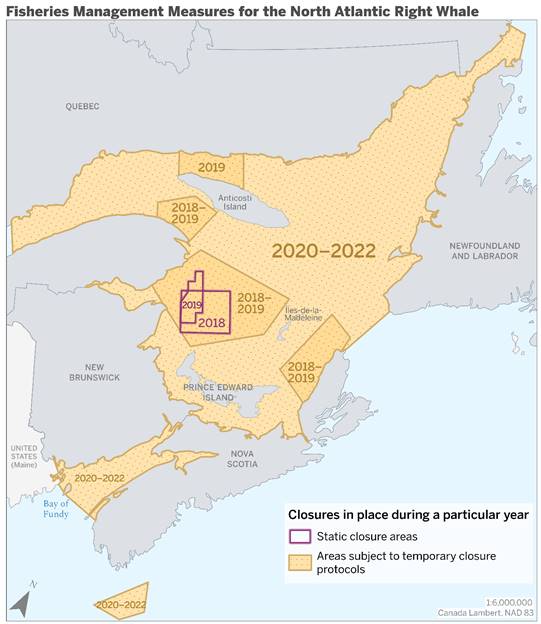

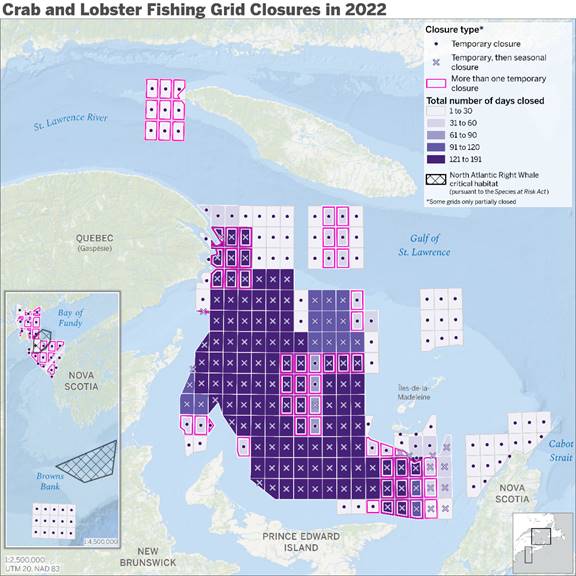

In 2018 and 2019, static and dynamic fishing area closures were implemented for non‑tended fixed gear fisheries[34] in the Gulf of the St. Lawrence. Since 2020, closures have been possible anywhere in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Bay of Fundy, as well as in the NARW critical habitat areas of the Grand Manan Basin and the Roseway Basin. Figure 2 shows the evolution of these measures.

Figure 2—Areas Subject to Dynamic and Static Fisheries Management Measures for All Non-Tended Fixed Gear Fisheries in 2018, 2019 and 2020 to 2022 for the Protection of North Atlantic Right Whales

Source: Map prepared in 2023, using data from Natural Resources Canada, Administrative Boundaries in Canada – CanVec Series – Administrative Features, 1 March 2019; and Government of Canada, Fishery Notices Related to North Atlantic Right Whales, 2018–2022. The following software was used: Esri, ArcGIS Pro, version 3.1.0. Contains information licensed under Open Government Licence – Canada.

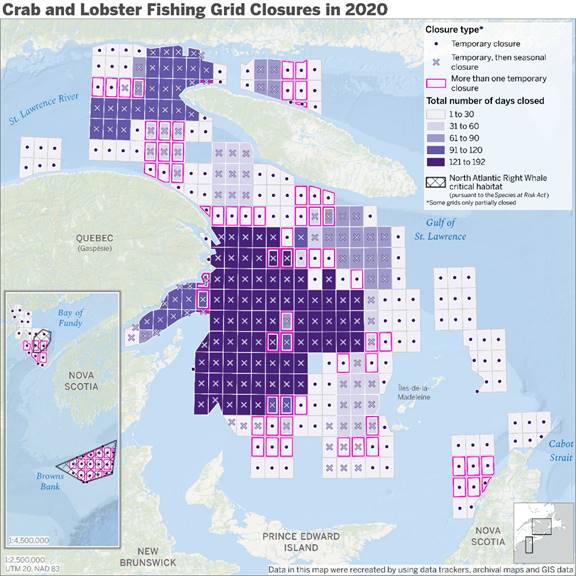

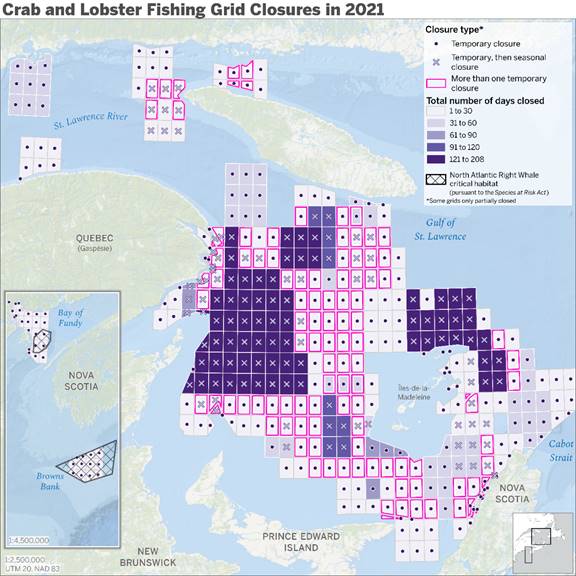

The Committee heard that, since 2020, all closures begin as dynamic, temporary closures and become season-long closures if there are repeated sightings of NARW in the same area. The visual or acoustic detection of a NARW leads to an area being closed to fishing for all non-tended fixed gear, such as crab and lobster gear, for 15 days. In 2020, the detection of a NARW at any point during the 15-day dynamic closure led to the closure becoming a season‑long closure. In 2021, the closure protocol was modified so that a NARW detection during days nine to 15 led to the closure of the area for the rest of the fishing season in the Gulf of St. Lawrence or extended the closure by an additional 15 days in the Bay of Fundy, Roseway Basin and Grand Manan Basin.[35] Adam Burns stated that fishing area closures are “supported by a comprehensive monitoring regime to detect the presence of whales in our waters, including flights, vessels and acoustic monitoring.”[36] Figures 3 to 5 shows the duration of dynamic closures as well as those that became seasonal closures between 2020 and 2022.

Figure 3—Duration of Temporary Closures and Grids Subject to Seasonal-Closures in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Bay of Fundy in 2020

Sources: Map prepared in 2023, using data from Natural Resources Canada, Administrative Boundaries in Canada – CanVec Series – Administrative Features, 1 March 2019; Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Atlantic Marine Mammal Hub, Spatial data regarding crab and lobster fishing grids in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, provided on 13 March 2023; and Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Critical Habitat of Species at Risk, 26 September 2016. The following software was used: Esri, ArcGIS Pro, version 3.1.0. Contains information licensed under Open Government Licence – Canada. The ocean basemap layer is the intellectual property of Esri and is used under licence, © 2022 Esri and its licensors.

Note: The spatial dataset borrower recognizes the limitations of the data and understands that the Atlantic Marine Mammal Hub does not warrant or guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the data provided for 2020.

Figure 4—Duration of Temporary Closures and Grids Subject to Seasonal-Closures in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Bay of Fundy in 2021

Sources: Map prepared in 2023, using data from Natural Resources Canada, Administrative Boundaries in Canada – CanVec Series – Administrative Features, 1 March 2019; Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Atlantic Marine Mammal Hub, Spatial data regarding crab and lobster fishing grids in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, provided on 22 February 2023; and Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Critical Habitat of Species at Risk, 26 September 2016. The following software was used: Esri, ArcGIS Pro, version 3.1.0. Contains information licensed under Open Government Licence – Canada. The ocean basemap layer is the intellectual property of Esri and is used under licence, © 2022 Esri and its licensors.

Figure 5—Duration of Temporary Closures and Grids Subject to Seasonal-Closures in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Bay of Fundy in 2022

Source: Map prepared in 2023, using data from Natural Resources Canada, Administrative Boundaries in Canada – CanVec Series – Administrative Features, 1 March 2019; Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Atlantic Marine Mammal Hub, Spatial data regarding crab and lobster fishing grids in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, provided on 12 December 2022; and Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Atlantic Marine Mammal Hub, Excel file regarding crab and lobster fishing grid closures in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, provided on 12 December 2022; Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Critical Habitat of Species at Risk, 26 September 2016. The following software was used: Esri, ArcGIS Pro, version 3.1.0. Contains information licensed under Open Government Licence – Canada. The ocean basemap layer is the intellectual property of Esri and is used under licence, © 2022 Esri and its licensors.

There was a consensus among witnesses, including Paul Lansbergen, President of the Fisheries Council of Canada, and Molly Aylward, Executive Director of the Prince Edward Island Fishermen's Association, that dynamic closures are a more effective approach than season-long closures.[37] Witnesses also explained that they seek further refinement of DFO’s approach. Molly Aylward suggested that DFO review static closures monthly to determine if reopening the grid would be high or low risk.[38] Bonnie Morse suggested that “there is not scientific evidence to support a 15-day closure based on a single sighting.”[39]

Recommendation 9

That, since most detections of single NARWs involve transiting whales that will not spend several days in the same grid, DFO modify the fishing area closure measures for the 2023 season in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the Bay of Fundy and Roseway Basin as follows:

- When three NARWs are detected, an area around the point of detection (approximately 2,000 km2) will close temporarily for a period of 10 days and may reopen after that time if no other whale is visually and acoustically detected between days 7 and 10.

- If three NARWs are detected during days 7 to 10 of a closure, the area around the point of detection is closed for another 10-day cycle starting on the day of the second detection.

- In other parts of Atlantic Canada, closures will be considered on a case-by-case basis, with special consideration for sightings of three or more whales or a mother and calf pair.

Recommendation 10

That DFO promote the multiple-whale trigger and fill the knowledge gaps needed to use this tool. NARW protection measures should take whale behaviour in feeding grounds into account to make management measures more effective.

Recommendation 11

That in fishing areas NARWs transit through, but do not gather in to feed, DFO not impose full fishing season closures.

Recommendation 12

That, considering the low abundance of NARW at the start of the season and their behaviour in transit, DFO not impose seasonal closures in May, because there are no conservation gains to be made at that point in the NARW migratory process, prior to the critical period.

The current DFO approach allows fishing zones to be closed when the presence of NARW is confirmed by acoustic buoys, but the data from the buoys are not used to reopened them. Robert Haché, General Manager of the Association des crabiers acadiens, believed that detections from hydrophones are not precise enough to close fishing areas because they simply detect NARW calls within a 40-kilometre radius.[40] Martin Noël, President, Association des pêcheurs professionnels crabiers acadiens with the Fédération régionale acadienne des pêcheurs professionnels, requested that acoustic buoys also be used to reopen closed zones, giving the example of a situation where weather prevents surveillance aircraft from taking off but the buoy is still functional.[41] Lyne Morissette suggested that acoustic buoy detections could be used to reopen fishing areas, particularly if triangulation could be used to identify the exact location of NARWs.[42] Melanie Giffin, Marine Biologist and Industry Program Planner with the Prince Edward Island Fishermen's Association, agreed that a methodology should be developed to reopen closed zones using acoustic buoys, so long as one buoy controlled nine grids.[43] However, Sean Brillant explained that acoustic buoys are not used to reopen closed fishing area because NARW do not always make sounds, and the absence of whale vocalisation does not mean the absence of NARW.[44]

Recommendation 13

That DFO use the most up to date visual and acoustic NARW detections, including aerial and at-sea surveillance and hydrophones detections, when deciding whether to close or reopen fishing areas.

Recommendation 14

That current criteria for regulating in-season fishing closures be examined to explore possibilities of re-opening in-season if NARWs have moved out of closed areas.

Recommendation 15

That the government ensure the least amount of fishing days are lost when a closure is announced by doing daily verification of NARW presence once an area is closed and open it immediately after the NARW is no longer detected.

Recommendation 16

That DFO ensure that decisions made to protect NARW

- are adaptive and responsive to changes in migratory behaviours and distribution of NARWs caused by the climate crisis and other potential influencing factors; and

- prioritize zones were NARWs are demonstrating foraging behaviours or present in social aggregations.

Recommendation 17

That DFO document the inter-annual and intra-annual variability in NARW distribution in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and quantify the effectiveness of area closures in relation to this variable distribution.

Witnesses such as Martin Mallet, Executive Director, Maritime Fishermen's Union, stated that fishers having to move their fishing equipment due to a closure carried a significant cost.[45] Martin Mallet stated that it would be “disastrous” if lobster fishers were forced to take all their traps out of the water for two weeks, and added that the shallow water protocol, which excludes fishing areas of 10 fathoms or less from closures, has worked well and has allowed lobster fishers to continue operating.[46] Witnesses such as Martin Mallet and Bonnie Morse estimated that the closure of a fishing area can lead to millions of dollars worth of lost revenues.[47] Melanie Giffin stated that fishing area closures caused Prince Edward Island (PEI) fishers to struggle to catch their snow crab quota in 2021.[48]

Recommendation 18

That DFO consider, and publish an annual report on, the socio-economic and environmental impacts on coastal communities, fish harvesters and processors due to the closure of fishing areas and changes to required fishing gear for the protection of the NARW.

Recommendation 19

That DFO and the Government of Canada recognize that there is significant support to protect NARWs and develop long term planning to maximize the conservation of the species while minimizing negative impacts on Canadian fish harvesters and human marine activities.

Robert Haché described how fishing closures have caused snow crab fishers to congregate in the remaining viable open fishing locations, concentrating the fishing effort to those areas.[49] Mathieu Noël, Director of Opilio at the Maritime Fishemen’s Union, agreed and explained that when considering “fishing grounds [that] are active and productive”, the available area is “fairly limited”.[50] Robert Haché argued that many of the productive fishing areas had been pointlessly closed because the acoustic buoys signaling the closure control a broad area, and because NARWs being detected are only transiting through the closed area towards feeding grounds.[51]

Detecting North Atlantic Right Whales

Adam Burns stated that Canada has “implemented one of the world’s most advanced and near-real-time area closure programs to remove fishing gear […] where and when right whales are detected in Atlantic Canada and Quebec”.[52] NARWs in Atlantic Canada and Quebec can be detected acoustically or visually during surveillance flights or at-sea surveillance by CCG or DFO vessels.

Underwater microphones, called hydrophones, can detect whale calls 24 hours a day, seven days a week. As part of passive acoustic monitoring systems, hydrophones can be attached to the sea floor, mounted on surface buoys or mobile underwater gliders, or deployed from a vessel. Depending on ocean conditions, passive acoustic monitoring systems can detect whales tens of kilometres away.[53] Passive acoustic monitoring systems can currently detect if at least one whale is calling within the detection range of the hydrophone but cannot provide the exact location, the number of whales or differentiate between the call of one individual whale and another.[54]

Passive acoustic monitoring systems can be archival, recording whale calls for several months before the data is retrieved and analyzed; or near real-time, transmitting detections over satellite or cellular tower systems for validation in near real-time by marine mammal experts. Near real-time detections have been used to trigger fisheries management measures for NARW protection since 2020.[55] In 2022, Canada used six underwater gliders and eight hydrophones mounted on buoys for acoustic detection.[56] As previously mentioned, some witnesses believed that hydrophone detections should be used for the reopening of fishing areas and not just their closure, as is currently the case.

DFO aircraft fly over Atlantic Canada waters several times a week, weather permitting, in search of NARWs. Aircraft from Transport Canada’s National Aerial Surveillance Program monitor “designated shipping zones and certain areas of the Gulf of St. Lawrence.”[57] In 2022, Canada used up to six aircraft to support fishing and vessel traffic measures and NARW research.[58] Aircraft from NOAA in the U.S. also conduct surveillance flights over the Gulf of St. Lawrence.[59]

Recommendation 20

That Canada adequately resource equipment and operations for observation and conservation of NARWs in Canadian waters so as to eliminate the need for other countries to undertake operations in Canadian waters.

Recommendation 21

That DFO respond back to the Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans with full explanation of the government assets being used to monitor and track NARWs in Canadian waters and full explanation of US activities in Canadian waters related to NARW conservation measures.

Heather Mulock, Executive Director of the Coldwater Lobster Association, suggested that funding additional NARW monitoring was necessary since the hydrophones currently deployed by the Coldwater Lobster Association are of limited use because they do not provide accurate data in real time.[60]

Witnesses discussed the possibility of using tracking devices to monitor NARWs. The consensus was that this would be an effective option, but that the appropriate tracking device technology is not yet available. Kimberly Elmslie told the Committee that tracking devices that attach to the surface of a NARW have been used, but that they only stay attached for a couple of months since “these whales seem to understand that [the tracking devices are] on them and they hate them. They're violent and they rub [the tracking devices] off.”[61] Kimberly Elmslie also explained that, although subcutaneous trackers exist, the problem with using them in the case of NARW is that

the blubber layer is only about eight inches thick. Right now, the technology is to insert the tracker so that we could see where they are. The tracker itself is about 10 inches long. It's just too big and they would cause infections in a population that is already under tremendous stress.[62]

Gerard Chidley, Captain (as an individual), believed that placing a tracking device on NARW was the ideal solution to help protect the species. He suggested tracking devices would provide “insight into the life cycle of the right whale; [a] real-time record of the migration routes and any deviations, accurate time of entry and departure electronically, the ability to broadcast real-time positions to ocean users and [increase] co-operation from industry and other ocean users.”[63] Kimberly Elmslie also expressed a desire for improved tracking technology.[64]

Adam Burns stated that DFO is “studying predictive factors for the distribution of Calanus,[65] the food source for the North Atlantic right whale. […] One of the reasons our scientists are doing that work is to see if there are ways we might better predict where the aggregations of North Atlantic right whales will develop.”[66] However, he explained that this project is not yet advanced enough to influence management measures. Adam Burns stated that DFO is open to innovative solutions that will not reduce the level of protection for NARW.[67]

Recommendation 22

That DFO, in collaboration with the scientific community within and outside of the federal government, environmental groups, industry and First Nations, continue research on NARW, including:

- research and development of tracking devices that can be attached to NARWs to track their movements in near-real time;

- working with low earth satellite providers to track the movement of NARWs; and

- research to better understand the feeding, transiting and social behaviours of NARWs and how these behaviour influence movement.

Modifying Fishing Gear

Gear marking has been required for all non-tended fixed gear fisheries in Atlantic Canada and Quebec since 2020. The mandatory gear marking for all ropes used to attach fishing gear to a buoy or any other floating apparatus (vertical line) “consists of specific colours that must be used to correctly identify fishing ropes in different fisheries, regions and sub-regions in Canada.”[68] The mandatory gear marking facilitates efforts to distinguish between U.S. and Canadian gear involved in marine mammal entanglements, as well as identifying the fishery itself.

When speaking about the implementation of the mandatory gear marking, Melanie Giffin felt that the process had been rushed and that answers to questions were not always available. She described the situation as follows:

[A]bout a month before the season started, DFO announced the mandatory requirement for gear marking and it became a scramble on the East Coast for people to find the proper coloured twine. There were issues that came up and trying to get answers out of conservation protection officers here on P.E.I. became a challenge because they didn't even have all of the answers to the questions we had.[69]

Recommendation 23

That DFO departmental staff be adequately trained, oriented and equipped to provide timely information on changing regulations to protect NARWs to harvesters and mariners.

Whalesafe Gear

Adam Burns stated that to “reduce the threat of serious injury in the event that a whale is entangled, the department is working with the fishing industry and partners in Atlantic Canada and Quebec to develop whalesafe fishing gear.”[70] According to DFO, there are two general categories of whalesafe gear:

- Low breaking-strength rope or links that are designed to break at 1,700 lbs. of force. This gear will make it easier for entangled whales to free themselves and reduce the risk of serious injury; and

- Systems that allow fishing gear to be deployed without vertical line in the water, either rope-on-demand systems that stow buoy lines at the sea floor, or inflatable bag systems that eliminate buoy lines. These are released by an acoustic signal sent from the fishing vessel.[71]

At the time the Committee undertook this study, whalesafe fishing gear was to be required for all fixed gear fisheries in Atlantic Canada and Quebec by January 2023. After the completion of this study, DFO announced that the deadline for the implementation of low breaking-strength fishing gear was being extended to 2024 to allow more time for testing and implementation.[72] Witnesses expressed frustration at the lack of sufficient consultation with fishers. For example, Lyne Morisette had noticed over the past five years a “distinct lack of consideration for fishers, who are invited to meetings, on a few days' notice and are seen more as decorations or names on a list, rather than being included for all the highly relevant input they can provide to discussions and decisions.”[73]

Through the Whalesafe Gear Adoption Fund, DFO budgeted up to $20 million between 2020 and 2022 towards the “purchase, testing and refinement of whalesafe gear with the goal of making this innovative equipment ready to use in 2024.”[74]

Almost all witnesses agreed on the importance of tailoring the methods used to protect NARW to the conditions present in different fishing areas. Heather Mulock described the importance of tailored methods as follows:

We must ensure that the fishery management measures put in place to protect North Atlantic Right Whales are appropriate for the fishing area in which they are being implemented, and that they’re not counter-productive. Introducing management measures that do not work will create economic hardship for thousands of harvesters, all while putting other species at risk with further entanglements.[75]

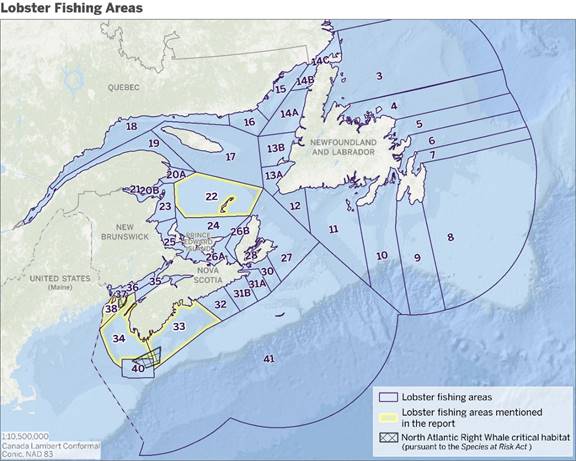

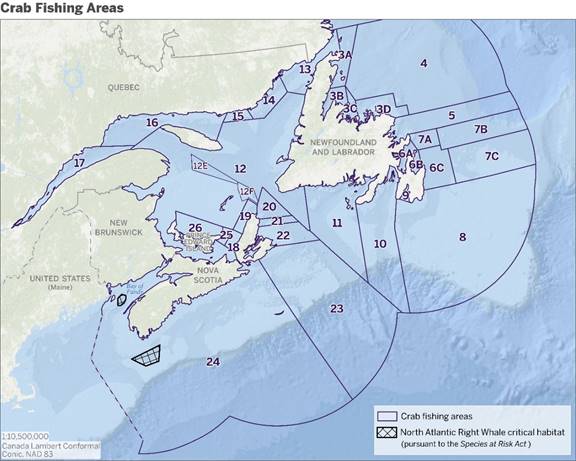

Moira Brown, Senior Scientist at the Canadian Whale Institute (as an individual), explained that DFO’s one-size-fits-all approach was a quick response to the 2017 unusual mortality event, and that Canada was now able to start more narrowly tailoring its response for a more sectoral approach.[76] Figures 6 and 7 show the lobster fishing areas and crab fishing areas in Atlantic Canada and Quebec, including the areas specifically mentioned in this report.

Figure 6 — Lobster Fishing Areas in Atlantic Canada and Quebec

Sources: Map prepared in 2023, using data from Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), Administrative Boundaries in Canada – CanVec Series – Administrative Features, 1 March 2019; Atlantic Fishery Regulations, 1985, SOR/86-21, Schedule XIII; Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Critical Habitat of Species at Risk, 26 September 2016. The following software was used: Esri, ArcGIS Pro, version 3.1.0. Contains information licensed under Open Government Licence – Canada. The ocean basemap layer is the intellectual property of Esri and is used under licence, © 2022 Esri and its licensors.

Figure 7 — Crab Fishing Areas in Atlantic Canada and Quebec

Sources: Map prepared in 2023, using data from Natural Resources Canada, Administrative Boundaries in Canada – CanVec Series – Administrative Features, 1 March 2019; Atlantic Fishery Regulations, 1985, SOR/86-21, Schedule IX; Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Quebec and Gulf Regions: Fishing Areas for Snowcrab; and Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Critical Habitat of Species at Risk, 26 September 2016. The following software was used: Esri, ArcGIS Pro, version 3.1.0. Contains information licensed under Open Government Licence – Canada. The ocean basemap layer is the intellectual property of Esri and is used under licence, © 2022 Esri and its licensors.

Rope-on-demand Fishing Gear

Witnesses had mixed reactions to rope-on-demand fishing gear, and these mostly varied based on the region in which the gear was used. Fishers from Nova Scotia and Newfoundland described the difficulties in using rope-on-demand gear because of currents or depths. However, fishers from the Gulf of St. Lawrence had more positive feedback about the use of rope-on-demand gear. As previously noted, since the Committee finished this study, DFO has pushed back the date requiring whalesafe fishing gear such as rope-on-demand fishing gear to 2024.

Rope-on-demand fishing gear allows fishers to fish in zones which have been closed due to the detection of a NARW. Philippe Cormier, President of CORBO Engineering, stated that, during the 2022 season, 20 fishers were able to use rope-on-demand fishing gear to capture 203 tonnes of snow crab in fishing areas which were otherwise closed to fishing because of dynamic or season-long closures. However, he acknowledged that despite positive results, technological and logistical issues persist and must be overcome before rope-on-demand gear could be implemented at a larger scale.[77]

Sean Brillant stated that the effectiveness on rope-on-demand gear was demonstrated by his experience with “600 trials of seven different ropeless systems” conducted with “14 different snow crab and lobster fishermen throughout the maritime provinces.”[78] Through the Whalesafe Gear Adoption Fund, Sean Brillant was involved in a lending program that supplied 54 units of rope-on-demand whalesafe gear to 10 fishers based in Tignish, P.E.I. in 2021. Sean Brillant recounted the successes those fishers had with rope-on-demand technology:

They fished for between four to six weeks in closed zones, using on-demand or ropeless gear. They did more than 150 hauls and landed more than 370,000 pounds of snow crab. This also eliminated 500 buoy lines from the area, making the entire Gulf that much safer for right whales.[79]

Recommendation 24

In light of witness testimony highlighting the need for further research and development surrounding whalesafe gear, that DFO continue to fund the Whalesafe Gear Adoption Fund.

Gilles Thériault, President of the Association des transformateurs de crabe du Nouveau-Brunswick, attested that he believed rope-on-demand was the definitive solution to marine mammal entanglements based on the successes in the Gulf of the St. Lawrence, and the speed at which the technology was being developed and adopted.[80]

Daniel J. Fleck, Executive Director or the Brazil Rock 33/34 Lobster Association, suggested that rope-on-demand fishing gear would not be practical in lobster fishing areas (LFAs) 33 and 34 south of Nova Scotia because the “fishery is largely conducted during hours of darkness. With such limited visibility, with no ropes or buoys to indicate the locations of previously set gear by other captains the trawls would be set over one another.”[81] Shawn Muise, Director and Captain, Brazil Rock 33/34 Lobster Association, agreed that fishers need visual indicators on the surface of the water to avoid setting their traps on top of traps belonging to others.[82] Daniel J. Fleck assessed that if rope-on-demand gear set over one another tangled together, it would be difficult to retrieve and could become ghost gear.[83]

Glen Best, Fish Harvester at Glen and Jerry Fisheries Inc (as an individual), expressed doubts that rope-on-demand gear would be suitable for the deep water and marine environment in Newfoundland.[84] Sean Brillant indicated that their organization had not conducted rope-on-demand gear trials in waters as deep as those of Newfoundland’s fisheries, and that testing, in collaboration with fishers, should be conducted to see if the technology works in that environment.[85] Moira Brown indicated that the technology for rope-on-demand gear started in the oceanography business to recover gear from 5,000 feet of water, so it is likely that the gear could be developed to work in deep water fisheries.[86]

One of the criticisms of rope-on-demand gear was its cost – between $4,000 and $5,000 per rope-on-demand unit, in addition to the costs of the equipment required to auto‑coil the rope.[87] Molly Aylward believed that the cost of the rope-on-demand gear was prohibitive and did not make economic sense.[88] The up-front cost of rope-on-demand gear made the risks of losing that gear more punishing, in the event of malfunction.[89] Martin Noël described the cost associated with this new technology, and how it had modified the harvesting approach in the Gulf:

Each unit costs roughly $5,000. The harvesters who did the testing had five units, so the total cost was around $25,000. Traps were attached to the unit to catch the crab. To reduce costs, we went from fishing with a single trap, or pot, to fishing with a number of pots connected to a unit. We were able to gain some experience that way, go through the learning curve and come up with a new harvesting method. It obviously costs a whole lot more than harvesting the traditional way, but it gives us the ability to fish in areas that would otherwise be off limits for the protection of [NARW].[90]

Recommendation 25

That gear required as a result of NARW protection measures be affordable to harvesters.

Recommendation 26

That the government amend the regulations so that all fishers can use rope-on-demand gear in closed areas and that funding be made available to cover part of the cost of this gear until it is proven commercially viable.

Recommendation 27

That future planning around whalesafe gear consider options to reduce financial implications on fishers and coastal communities and that such changes are communicated to fishers in a timely manner.

Weaklink Rope Fishing Gear

There was general consensus among witnesses that the weaklink rope, a rope with a lower breaking point that is intended to allow NARW to break the fishing rope after an entanglement, is not an effective solution. In its present state, the Committee heard that weaklink rope could create additional risks for NARW, the environment and fishing crews. As previously noted, since the Committee finished this study, DFO has pushed back the date requiring whalesafe fishing gear such as weaklink rope to 2024.

Witnesses suggested that using weaklink rope where it is not suitable could contribute to ghost gear.[91] For example, Keith Sullivan, President of Fish, Food and Allied Workers – Unifor, and Gerard Chidley agreed that it is not possible to use weaklink rope in the crab fishery off the coast of Newfoundland.[92] This fishery occurs in significant depths (with an average depth of 600 feet, and as deep as 1,500 feet) and utilizes multiple traps per fishing line; both of these factors contributing to strain on fishing lines.[93]

Keith Sullivan also suggested that because weaklink ropes are not strong enough to haul the long series of traps used in the Newfoundland crab fishery, a greater number of lines with fewer traps attached would have to be used. This, Keith Sullivan stated, would likely “lead to increased entanglements of other marine mammals that are prevalent in our waters.”[94]

Recommendation 28

That ghost gear retrieval operations continue in areas where gear has been reported lost and in areas frequented by NARWs and that the necessary funding be granted to carry out these operations.

Shawn Muise indicated that weaklink rope was unreliable, and had broken, at times, at weights as low as 500 psi. He told the Committee of an outing at depths of 100 to 115 fathoms that had a 100% failure rate when retrieving lobster gear with weaklink rope. Most of the whalesafe gear, either a plastic weak link or a nylon sleeve, did not reach the surface of the water but when it did, most failures occurred when the weaklink rope reached the pulley over the side of the boat. Shawn Muise also noted that their tests were conducted in favourable summer conditions, whereas the LFA 33/34 fisheries takes place in harsher fall and winter conditions.[95] Heather Mulock described the unique challenges of LFA 34 for implementing whalesafe gear, with one rope manufacturer informing her that even with extensive research and development, it was unlikely that a low breaking-strength rope could be developed for the region “given the tide strength, the hard bottom, and significant gear conflict.”[96]

Philippe Cormier, whose company works on developing whalesafe gear, indicated that, while there is progress being made with weaklink rope, current results demonstrate that the technology requires a few years of development.[97] Lyne Morissette indicated that weaklink rope has been tested and worked in fisheries in England, Australia and Brazil, but that it needs to be tested in all conditions in which it will be used.[98]

Safety of Whalesafe Gear and Fisheries Management Measures for the Protection of the North Atlantic Right Whale

Witnesses expressed concern over the safety of some whalesafe gear, especially weaklink fishing rope. Heather Mulock explained that unfavourable results from at-sea trials with different whalesafe gear types amplified concerns for the safety of crew and increased the risk of gear loss.[99]

Gerard Chidley described potential consequences of fishing rope breaking or parting, given the immense tension on the fishing rope: “[i]f that rope parts at a critical time, our crew member handling that could end up with severe lacerations to the hands, the face or anything else.”[100] Keith Sullivan added that “DFO has provided no evidence that [whalesafe] gear is safe or effective for the fishery. They have provided no evidence that the gear has been fully tested and would hold up to North Atlantic tides, ice conditions and the heavy strains in deep water.”[101]

Jean Lanteigne identified other sources of concern for fisher safety related to both the date of the opening of the snow crab fishing season and the rush to remove fishing gear after the closure of a fishing area because of a NARW detection. He believed that efforts to catch quotas as early as possible in the season, before the arrival of NARW and the beginning of dynamic and seasonal closures, can lead to fishing in winter-like conditions which can be dangerous to crews. As a result, he believed it was important to follow the advice of the Committee for Setting the Opening Date for the Fishery to set the date for the opening of the snow crab season in Area 12. Jean Lanteigne also described as more dangerous the situations where fishers had to “move traps quickly [from an area being closed because of a NARW detection] before going into areas where they are not sure fishing is possible.”[102]

Recommendation 29

That, to develop gear that has the support of fishers, DFO continue funding the development and improvement of whalesafe gear and consider its safety and efficacy according to region.

Implementation Deadline of Whalesafe Gear

As previously stated, at the time the Committee heard testimony, the requirement to use whalesafe gear in fixed gear fisheries across Quebec and Atlantic Canada was set to January 2023. Witnesses, such as Melanie Giffin, Michael Barron, President of the Cape Breton Fish Harvesters Association, and Paul Lansbergen agreed that this deadline was not feasible.[103] The Committee heard that procurement of whalesafe gear has been an issue and that it has not been sufficiently tested in different environments.[104] Michael Barron stated that fishers “are currently being rushed into costly and potentially unsafe gear modifications that lack a proven track record of success.”[105]

Witnesses said gear testing was insufficient, and that the gear was not ready to be implemented. Martin Noël stated that:

In terms of the requirement to modify fishing gear, including modifications effective as of January 2023, I have to say that we have concerns. The aim is to reduce the length and the severity of potential entanglements. Tests have been done at sea over the past few years which have allowed us to retain certain methods and reject others, but it is still not possible to determine which methods are the most efficient for achieving our goal.[106]

Molly Aylward criticized the amount of notice given to fishers about new gear requirements since “P.E.I. harvesters normally prep rope a year in advance of the season.”[107] When the gear marking requirement was implemented, it was announced one month before the start of the fishing season, causing a scramble and procurement issues. Molly Aylward worried that a similar situation would happen with the requirement to use weaklink fishing gear, a requirement that, in her view, lacks detail.[108] Gerard Chidley was also critical of the implementation plans. He believed these plans would increase costs on fishers, increase ghost gear and ghost fishing due to the unreliability of the new gear, and increase the use of fuel by fishers.[109]

Recommendation 30

That DFO clearly communicate new requirements for harvest gear and their use to harvesters and mariners early enough to allow for the time to purchase necessary gear and to make the required equipment modifications despite supply chain challenges.

Recommendation 31

That DFO ensure that future requirements to adopt new gear types to avoid NARW entanglement be fully researched, designed and tested before being implemented to

- ensure the gear requirements are acceptable to the industry and safe for fishers to use; and

- avoid causing the use of more vertical or floating line or increasing the risk for lost gear or ghost gear and the resulting plastic pollution in our oceans.

Recommendation 32

That DFO postpone the deadline for implementing whalesafe gear to give fishers and authorized gear suppliers time to adapt, and that scientists, non-governmental organisations and industry receive adequate funding to continue testing to develop a technology that is safe for fishers, presents no risk of entanglement to NARW and does not result in an increase in ghost gear.

Regional Specificity

In addition to the difficulties implementing rope-on-demand and weaklink gear in different areas of Atlantic Canada and Quebec, witnesses described regional differences they believed should be considered while developing protection measures for the NARW. Many witnesses stated that a “one-size-fits-all” solution would not work across all fisheries and regions.

Glen Best and Keith Sullivan agreed that Newfoundland waters pose little risk of entanglement for NARW. Keith Sullivan stated that NARW are only sporadically in the region, because Newfoundland and Labrador waters are not the right habitat for the animal.[110] Glen Best stated: “We don’t have Right Whales. We haven’t had closures. We don’t face the same issues as they have in the Gulf when they get a concentration of [NARW] and have closed fishing areas.”[111] Heather Mulock stated, “there have been no confirmed cases or documented evidence of [NARW] ever being entangled in lobster fishing gear in LFA 34.”[112]

Recommendation 33

That the government consider where NARW sightings have been, and not impose weaker gear in areas that do not experience NARW visits (i.e., Newfoundland & Labrador).

Glen Best criticized the fact that the requirement to use weaklink rope would apply to all types of different fisheries, from a lobster fishery that can take place in two fathoms of water, to a crab fishery in 200 fathoms, or a turbot fishery that takes place on the edge of the continental shelf in depths of up to 650 fathoms.[113]

Molly Aylward stated that 99% of PEI lobster fishers conduct part of their operation in less than 10 fathoms of water, a shallow depth where interaction with NARW is unlikely.[114] If an exclusion zone were created at 10 fathoms, this would benefit fishers, without endangering NARW. Jean Côté, Scientific Director of the Regroupement des pêcheurs professionnels du sud de la Gaspésie, iterated the same point about the Gaspésie lobster fishery which occurs in less than 20 fathoms of water and does not encounter NARW.[115]

Bonnie Morse stated that the lobster fishery in LFA 38 near Grand Manan likely does not overlap with NARW presence because the fishing season begins in November, and NARW leave their critical habitat in the Grand Manan Basin in early fall.[116] Bonnie Morse also stated that well over half of the lobster quota is caught in the first few weeks of the season, and that a closure at that early point because of a transiting NARW causes significant economic hardship. For this reason, Bonnie Morse called for more accurate detection of NARW in that region.[117]

Recommendation 34

That whalesafe gear not be required when fishing seasons do not correspond to the presence of NARWs.

Charles Poirier, President of the Rassemblement des pêcheurs et pêcheuses des côtes des Îles, argued that the NARW detections which resulted in closures for LFA 22, around the Magdalen Islands, are caused by transiting NARWs on their way to the Gulf of the St. Lawrence. For this reason, Charles Poirier suggested that initial dynamic closures be reduced to 7 days after a NARW detection.[118]

Sean Brillant and Susanna Fuller, Vice-President, Operations and Projects, Oceans North, reminded the Committee that climate change is causing NARWs to change their distribution. The Gulf of St. Lawrence, where “most of the North Atlantic right whales have been found for the past several years, is warming faster than any other part of Canada's ocean. It's likely that the prey that the North Atlantic right whale are feeding on will move again, and whales will follow.”[119] This could lead to fisheries, such as those in Newfoundland, who do not currently encounter NARW, encountering them in the future.[120]

Recommendation 35

That DFO make decisions and plans to protect the NARW that are appropriate for the different fisheries and ocean conditions found in the North Atlantic region rather than blanket regulations, and that they be developed in collaboration with scientists, environmental groups, industry and First Nations.

Vessel Slowdowns and Corridors in the Gulf of St. Lawrence

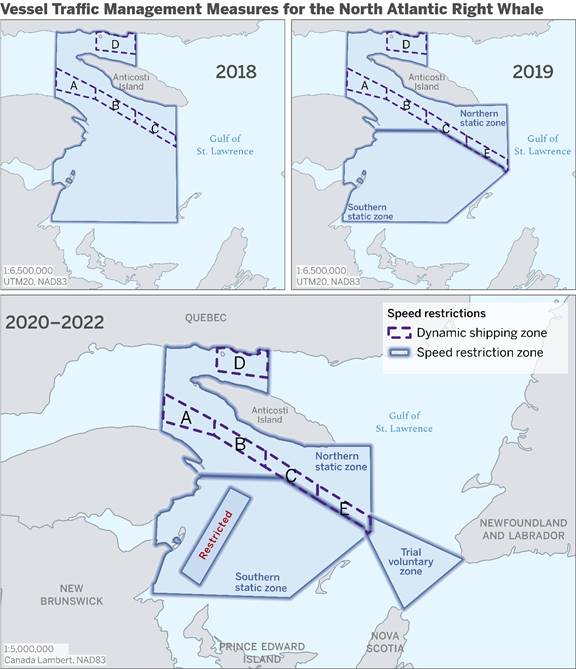

As shown in figure 1, when the cause of death of a NARW could be identified between 2017 and 2021, vessel strikes were identified as the cause of more deaths than entanglement in fishing gear. Transport Canada has implemented vessel slowdowns in the Gulf of St. Lawrence to reduce the number and the severity of vessel strikes on NARW since the summer of 2018. In 2018, the measures applied to vessels over 20 metres in length. Starting in 2019, the measures have applied to vessels over 13 metres in length. In 2022, traffic management measures included temporary measures instated after a NARW detection, mandatory season-long slowdown and exclusion zones, and a trial voluntary slowdown area in the Cabot Strait. Fines of up to $250,000 can be issued to vessels that are non-compliant with mandatory vessel traffic management measures. Figure 8 shows the evolution of vessel traffic management measures between 2018 and 2022.

Figure 8—Vessel Traffic Management Measures to Help Protect North Atlantic Right Whales in the Gulf of St. Lawrence between 2018 and 2022

Source: Map prepared in 2022, using data from Natural Resources Canada, Administrative Boundaries in Canada – CanVec Series – Administrative Features, 2019; Transport Canada, Protecting the North Atlantic right whale: speed restriction measures in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, 2022 (and 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021). The following software was used: Esri, ArcGIS Pro, version 3.0.2. Contains information licensed under Open Government Licence – Canada. The ocean basemap layer is the intellectual property of Esri and is used under licence, © 2022 Esri and its licensors.

Marc Mes explained that once whales are identified in a restricted zone, the speed restriction is implemented and “any vessel that goes outside of that speed for any more than 95 seconds is automatically notified [by the CCG] and a contravention is issued and sent to Transport Canada for follow up.”[121] The slowdowns are communicated to mariners through navigational warnings, notices to mariners and postings that go through the CCG’s marine communications and traffic services centre at Les Escoumins through continuous broadcasting messages about restrictions in specific areas.[122] Between 20 April 2022 and 15 November 2022, 10,606 vessel movements were monitored and 563 vessels were recorded at a speed above the limit or entering the restricted area. As of 17 January 2023, 555 of the 563 investigations of vessels recorded above the speed limit or entering the restricted area were closed, four were still pending and four penalties had been issued.[123] The penalties ranged between $6,000 and $10,500.[124]

Recommendation 36

That DFO commission an interdisciplinary study to determine

- if small fishing vessels from coastal fleets have ever been involved in a collision with a NARW; and

- the risk to NARWs from collisions with small fishing vessels by studying the oceanography (drifting carcasses of NARWs found dead), fishers’ knowledge (how they navigate and their history of collisions with NARWs) and the behaviour and pathology of NARWs in relation to collisions.

Consultation and Communication

Witnesses agreed that consultation with fishers is essential to implementing measures that will protect NARW.[125] However, witnesses from different regions reported different levels of consultation.

Gerard Chidley stated that, with regard to fisheries in Newfoundland, there had been limited consultation by DFO with industry.[126] Keith Sullivan stated that “there's been practically no engagement from DFO with fishers in Newfoundland and Labrador on this topic. In many ways, it's not surprising, because it's extremely uncommon to see these whales, and especially not overlapping with our snow crab and lobster fishing.”[127] Both Gerard Chidley and Keith Sullivan reported that DFO consultations had been limited to a few virtual meetings. Molly Aylward reported a similar lack of consultation about the PEI lobster fishery.[128]

On the other hand, Jean Lanteigne, referring to fisheries in New Brunswick, stated that there had been “unparalleled collaboration between NGOs, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans and the fishing industry.”[129] Gilles Thériault, also referring to fisheries in New Brunswick, stated that he observed excellent collaboration between industry stakeholders and federal and provincial governments to protect NARW and fulfill fishing quotas.[130]

Recommendation 37

That DFO meaningfully consult stakeholders in all regions of Atlantic Canada to assess the socio-economic costs of measures it is developing and work with stakeholders in a transparent and cooperative manner to avoid eroding access to ocean resources for those who depend on them.

Recommendation 38

That, when developing management approaches and new technology to ensure that fishers and endangered whales such as the NARW can coexist, DFO develop a mechanism to ensure input from, and meaningful consultation and collaboration with, concerned stakeholders including:

- fishers using the gear;

- those with local and traditional knowledge of fishing;

- those with traditional Indigenous knowledge; and

- experts who know what measures will be feasible and most effective at protecting whales.

Recommendation 39

Given the impact of fishery closures on the livelihoods of all fishers, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, as a result of the presence of NARWs, that reasonable, adequate, and meaningful consultation with stakeholders be undertaken.

Recommendation 40

That the continued restoration of the NARW remain an important conservation effort by all Canadians.

Adam Burns spoke to the role of Indigenous communities in protecting NARW and the importance of consulting with them. Adam Burns informed the Committee that:

Indigenous communal, commercial and moderate livelihood fishing activities in [the] Maritimes region are subject to the same closure protocols as other commercial activities. In terms of FSC [food, social and ceremonial] fishing, our regional colleagues are currently working with First Nations to better understand their needs and ultimately to further integrate the FSC harvesting with the department’s overall approach to protecting North Atlantic right whales and other marine mammals. That meaningful consultation needs to be undertaken in advance of applying the same closure protocols to those FSC fisheries. The nations certainly were informed when these whale sightings occurred so that they could respond appropriately, based on their determinations.[131]

Recommendation 41

That, when delivering actions or decisions to support, or deny, Indigenous fish harvesting treaty rights and self-determination, the Government of Canada must publicly communicate their actions and decisions and the basis for them to foster greater understanding and reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous harvesters and communities and that this work be supported and enhanced by DFO officials.

Recommendation 42

That the Government of Canada foster opportunities to bring together fishers, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, impacted by decisions surrounding food, social and ceremonial (FSC) treaty rights and self-determination to participate in open dialogue, information sharing, and to promote mutual transparency.

Recommendation 43

That when the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard orders the closure of a fishery for conservation reasons, including the protection of an endangered species, that the closure apply to all fisheries, including commercial and FSC fisheries.

Marine Mammal Disentanglement Efforts

DFO collaborates with conservation groups and non-governmental organizations across the country to support marine mammal incident response networks under the umbrella of the Marine Mammal Response Program (MMRP). The MMRP tracks and responds to marine mammal entanglements, strandings, ship strikes and other threats.[132] Adam Burns explained that DFO’s “investments in the [MMRP] include $4.5 million in contributions to build capacity for safe and effective marine mammal response across Canada, as well as $1 million annually in operational support for our response partners.”[133]

Martin Noël stated that the Association des pêcheurs professionnels crabiers acadiens was “working closely with the Campobello whale rescue team to set up and train a disentanglement team for the Gulf.”[134] Kimberly Elmslie spoke with admiration of the people participating in whale disentanglement, including Moira Brown and fishers such as Martin Noël and Robert Haché. Kimberly Elmslie stated that these participants are “saving whales in really dangerous conditions. … [It] is a story that’s unique to Canada. We need to tell it.”[135] In addition to helping entangled NARW, gear disentangled from a whale can provide information about where it came from and what kind of gear it is. The information obtained can help refine solutions. Kimberly Elmslie advocated for permanent funding for disentanglement activities.[136]

Access to International Markets

The Marine Mammal Protection Act of the United States

The U.S.’s Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) was passed in 1972. The import provisions of the MMPA “aim to reduce marine mammal bycatch associated with international commercial fishing operations, requiring foreign fisheries exporting fish and fish products to the United States to have standards comparable in effectiveness.”[137] Exporting countries must apply for and obtain a Comparability Finding for each commercial fishery – such as lobster and snow crab fisheries – showing that the measures put into place to reduce marine mammal bycatch in their own country have comparable effectiveness to the ones in place in U.S. fisheries.

On 21 October 2022, NOAA Fisheries extended the deadline for exporting countries to obtain a Comparability Finding. The new deadline is 31 December 2023, one year later than the previous deadline of 31 December 2022. This extension will allow NOAA Fisheries more time to review the applications received from 132 nations for 2,504 foreign fisheries.[138]

Susanna Fuller stated that while the MMPA is an important piece of conservation legislation in the U.S., it is to some extent being used as a non-tariff trade barrier.[139] Jean Côté and Martin Mallet agreed that Canadian fisheries are being held hostage by the threat of U.S. trade barriers.[140]

Recommendation 44

That the Government of Canada take a proactive approach to relay the steps that Canada has taken to strengthen conservation of NARWs to legislators in the United States to pre-empt or counter false claims that negatively impact Canada’s seafood sector.

Recommendation 45

That DFO and the Government of Canada hold collaborative meetings with North American and international trading partners to ensure Canada’s fisheries are not unfairly or unnecessarily negatively impacted by requirements stipulated in trade agreements.

Recommendation 46

That the Government of Canada work with our American partners to ensure Canada’s NARW regulations are not used as a protectionist barrier under section 24 of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (CUSMA) to harm Canadian commercial fishing interests.

Potential Impacts on the Canadian Seafood Industry

Paul Lansbergen stated that the U.S. market is Canada’s top fisheries export market. He informed the Committee, that in 2021, exports to the U.S. were totalled $6.2 billion or 70% of Canadian seafood exports. Of this, lobster exports totalled $2.2 billion and crab—mostly snow crab— totalled $1.9 billion.[141] Jules Haché reported that New Brunswick exported $2.2 billion in seafood products in 2021.[142] Jean Côté informed the Committee that, since many processing facilities sell to the U.S., a closure of the U.S. market would also impact fishers that sell to processing facilities.[143]

Kimberly Elmslie expressed her concern on the potential impact the MMPA could have on Canadian lobster and snow crab fisheries. Kimberly Elmslie and Heather Mulock both assessed that it would be “absolutely devastating” for the East Coast to lose access to the U.S. markets.[144]

Paul Lansbergen explained that negative public perception of the Canadian seafood industry “can also impact our overall market reputation beyond those fisheries directly affected.”[145] Paul Lansbergen requested that when questions are posed on how DFO is managing fisheries resources, that the department defend itself and the industry, and stated that “DFO could do better in this respect.”[146]

Adam Burns stated that DFO communicates with environmental groups and counterparts in the U.S. so that Canada’s efforts to protect NARW are well understood.[147] According to DFO modelling, Canada has reduced the risk of NARW entanglement in snow crab fishery gear by 82%, and that risk reduction is one factor the U.S. considers when determining comparability.[148]

There was a consensus among witnesses that Canadian measures provided greater protection to NARW than the current U.S. protection regime. Adam Burns stated that, from DFO’s perspective, Canadian measures for the protection of NARW “are at least equivalent to those of the United States,” and that Canada is trying hard to have the exceptional Canadian measures understood by different groups in the U.S.[149] Philippe Cormier stated that Canada had made incredible strides over the last five years towards protecting NARW and assured the Committee that Canada is substantially ahead of the U.S. in this respect.[150]

Moira Brown affirmed that the Canadian fishing regime provides comparatively stronger protections for NARW than its U.S. equivalents, stating that “Canada has done more in five years to reduce risks [to NARW] than the States has done in 25 years.”[151] Moira Brown explained that Canada employs different measures, such as closing fishing areas, which are not used in the U.S., and that because Canada’s measures are different, they may or may not be recognize as equivalent. The bottom line, according to Moira Brown, is that Canada provides “a much safer situation for whales.”[152]

Recommendation 47

That the Government of Canada investigate the adequacy of US NARW protections, and publish regular findings of US conservation efforts for the endangered NARW.

Evaluation by an International Environmental Non-Governmental Organization of the Risks Posed by Canadian Fisheries to the North Atlantic Right Whale

In September 2022, Seafood Watch, an American sustainable seafood advisory list associated with the Monterey Bay Aquarium, released updated assessments for 14 fisheries in Canada and the U.S. “that use gear that pose risks to the endangered North Atlantic right whale.”[153] Seafood Watch assesses a fishery based on its impact on the harvested species, including overfishing; its impact on other species that are caught or used for bait; its impact on the seafloor and food web; and the effectiveness of management efforts to understand and minimize the fishery’s impact on marine life. Following this assessment, Seafood watch categorizes seafood into four categories, describing them as follows:

- Best Choice – Buy first, they’re well managed and caught or farmed in ways that cause little harm to habitats or other wildlife.

- Certified – Buy these certified products, they are equivalent to a Seafood Watch Good Alternative or better.

- Good Alternative – Buy, but be aware there are concerns with how they’re caught or farmed.

- Avoid – Don’t buy, they’re overfished or caught or farmed in ways that harm other marine life or the environment.[154]

Based on its assessment criteria, Seafood Watch attributed the “Avoid” status to the Canadian Jonah crab, rock crab, snow crab and lobster fisheries.[155]

Witnesses were critical of Seafood Watch’s rating. Adam Burns stated that DFO provided all the necessary information to Seafood Watch for them to make a fair and balanced assessment of Canada’s management regime. Unfortunately, according to Adam Burns, DFO does not believe that all this information was considered when Seafood Watch made their determination, and importantly, DFO believes that Seafood Watch “did not recognize the differences between Canada’s regime and that of the U.S.”[156]

Susanna Fuller stated that “Seafood Watch is not going to have a huge impact on trade. I don’t think we need to worry too much about it. I reviewed an early version of the report. I made many comments. It is unfortunate that they lumped Canada and the U.S. together.”[157]

Despite disagreeing with Seafood Watch’s evaluation of Canada’s fishing industry, witnesses expressed concern about the potential impacts such a rating could have on consumer perception of Canadian seafood products. Michael Barron stated that the Seafood Watch report “garnered significant media attention and caused great concern amongst the industry.”[158]

In order to protect Canadian fisheries’ reputations, witnesses argued that DFO should promote Canada’s management efforts and counteract negative messaging about the fishing industry.[159] Jules Haché suggested that initiatives aiming to protect NARW should be accompanied with a communication strategy to promote, on the international stage, the positive effects of the conservation measures.[160]

Recommendation 48

That the Government of Canada engage in clear and immediate public communication in Canada and internationally to

- promote the measures taken by Canadian fishers to protect the NARW, such as the retrieval of lost gear;

- address misinformation that harms the reputation of our seafood sector; and

- avoid conflict with the Marine Mammal Protection Act of the United States.

The same efforts should be made to open zones than to close them.

Conclusion

The Committee recognizes that the federal government has put in place effective fisheries management measures to protect NARW. However, the Committee heard that further refinement of the measures is required. Further consultations must occur with stakeholders, including on closure protocols and gear requirements, to develop management measures that allow fisheries and NARW to coexist safely wherever the animals are found. Management measures must be tailored to the requirements and realities of different regions and different fisheries. The Committee also heard that research must continue to develop technologies which allow for accurate tracking of NARW and that whalesafe gear requirements should only be implemented when they are proven to be effective and safe for both NARW and fishers. Finally, the Committee heard that the federal government should communicate, on the international stage, the conservation successes of Canadian fisheries.

[1] House of Commons Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans [FOPO], Minutes of Proceedings.

[2] FOPO, North Atlantic Right Whale.

[3] Government of Canada, “Distribution and population,” North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis).

[4] New England Aquarium, North Atlantic right whales’ downward trend continues as updated population numbers released, News release, 24 October 2022.

[5] Lyne Morissette, Marine Biologist and Environmental Mediator, M-Expertise Marine, Evidence, 21 October 2022.

[6] Government of Canada, “Distribution and population,” North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis).

[7] Adam Burns, Assistant Deputy Minister, Fisheries and Harbour Management, Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), Evidence, 18 September 2022; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), 2017–2022 North Atlantic Right Whale Unusual Mortality Event; and NOAA, North Atlantic Right Whale Causes of Death for Confirmed Carcasses.

[9] Government of Canada, “2.2 Recovery goal,” North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis): recovery strategy.

The goal is structured as an interim recovery target because a lack of data on the historical abundance of the species means a long-term target cannot be set until the data issue is resolved.

[10] Sean Brillant, Senior Conservation Biologist, Marine Programs, Canadian Wildlife Federation, Evidence, 21 October 2022; and Kimberly Elmslie, Campaign Director, Oceana Canada, Evidence, 21 October 2022.

[11] Pursuant to the Marine Mammal Protection Act of the United States, an unusual mortality event is defined as "a stranding that is unexpected; involves a significant die-off of any marine mammal population; and demands immediate response." See: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association Fisheries, Marine Mammal Unusual Mortality Events.

[12] Sean Brillant, Senior Conservation Biologist, Marine Programs, Canadian Wildlife Federation, Evidence, 21 October 2022.

[13] Baleen is a filter-feeding system inside the mouth of certain whale species, such as the NARW. Whales fill their mouths with water and use the baleen like a sieve to filter out their prey. A large part of the NARW diet is composed of copepods of the genus Calanus (small, shrimp-like animals).

[14] Government of Canada, Review of Effectiveness of Recovery Activities for North Atlantic right whales.

[15] Sean Brillant, Senior Conservation Biologist, Marine Programs, Canadian Wildlife Federation, Evidence, 21 October 2022.

[16] Brett Gilchrist, Director, National Programs, Fisheries and Harbour Management, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Evidence, 18 September 2022.

[17] Jean Lanteigne, Director General, Fédération régionale acadienne des pêcheurs professionnels, Evidence, 18 October 2022.