FOPO Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Science at the Department of Fisheries and Oceans

Introduction

On 1 February 2022, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans (the Committee) agreed to undertake a study to “examine how the Department of Fisheries and Oceans prioritizes, resources and develops scientific studies and advice for the department, how the results of scientific study are communicated to the Minister and Canadians, and how the minister applies data and advice provided by the department and other government departments to ministerial decisions.”[1] The Committee heard from 57 witnesses over nine meetings held between 26 April 2022 and 7 October 2022.

During the study, the Committee heard from current and former Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) employees, scientists, and representatives of Indigenous organizations, fishers and fisheries organizations, non-governmental organizations, and other stakeholders. These witnesses discussed the different elements involved in the formulation of science advice for decision-making including the collection and prioritization of scientific data within DFO, the Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) process used to generate peer-reviewed science advice, and the way science advice is provided to the Minister. The testimony heard by the Committee was somewhat polarized. Departmental officials told the Committee that DFO produces science advice for decision-making that is based on processes and policies that include collaboration and transparency and prevent conflicts of interest. However, other witnesses and stakeholders did not feel this was the case.

Witnesses agreed that DFO scientists do quality work. Dominique Robert, professor and Canada Research Chair in Fisheries Ecology at the Institut des sciences de la mer, Université du Québec à Rimouski, commended the quality of the work of DFO researchers and added that he believes they “are highly qualified to carry out the scientific work in their mandate.”[2] The Committee heard that DFO has many good policies that outline the process to be followed during the development of science advice but that these policies were not being followed. Andrew Bateman, Manager, Salmon Health at the Pacific Salmon Foundation, believed that “DFO’s current science advice aims are laudable on paper, but principles and guidelines are only as good as their implementation.”[3] Andrew Trites, Professor, Marine Mammal Research Unit, Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries at the University of British Columbia, stated that:

Canada is recognized as a world leader in fisheries and oceans research, which reflects well on the productivity and quality of research done by DFO, universities and other groups. However, I think we fall short as a country in terms of doing science that matters to fishermen, coastal communities, tourist operators and fisheries managers, among others. I think a new approach is warranted to ensure that the fisheries and oceans research undertaken in the coming years addresses the concerns expressed by the different sectors that have a significant stake in the health of Canada's fisheries and marine ecosystems.[4]

Policies and Guidelines for the Development of Science Advice Used in Decision-Making at Fisheries and Oceans Canada

At DFO, approximately 2,000 staff working at over 17 research institutes, laboratories and experimental centres are responsible for the production of scientific data, analysis, and advice.[5] The core role of science at DFO is to provide the evidence and data that will inform fisheries and oceans management decisions. For example, an important part of science at DFO is to support the fishing industry by providing stock assessment data which can feed into the eco-certification process completed by third parties that assess whether a fishery is well-managed and sustainable. Science staff at DFO also collaborate with international partners in research activities to support domestic and global policy‑making.

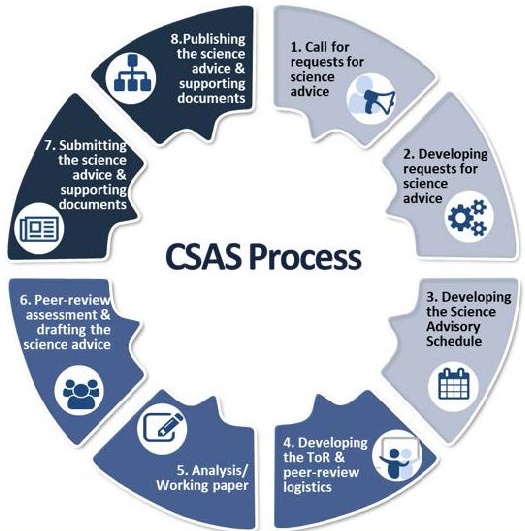

DFO’s CSAS coordinates the production of peer-reviewed assessments and science advice for departmental decision-makers. Figure 1 illustrates the process used by CSAS to generate science advice, which includes a peer review step.

Figure 1 : Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Process at Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada, “Science Advice,” Machinery of Government, 2021.

Pursuant to DFO policies, the participation of external experts in a CSAS process occurs by departmental invitation only. External experts are selected by a steering committee “based on their experience and expertise relevant to the subject matter of the review. Participants may include representatives of DFO, other government departments, First Nations, stakeholders, academia, environmental non-government organizations, as well as international experts.”[6] External experts have been invited to participate in the CSAS process since 1997.

The Policy on Science Integrity, which took effect in 2019, encourages “discussion based on differing interpretations of research and scientific evidence as a legitimate and necessary part of the research and scientific processes and, where appropriate, ensure[s] that these differences are made explicit and accurately represented.”[7] The Policy on Science Integrity also aims to ensure that DFO “research and science and any research or scientific products, as well as any associated communications, are free from political, commercial, client and stakeholder interference.”[8]

Mona Nemer, Chief Science Advisor at the Office of the Chief Science Advisor, explained that the Policy on Science Integrity is “meant to put in place the proper frameworks for the responsible conduct of research, including the ability of the scientists to publish their work without undue influence.”[9] Arran McPherson, Assistant Deputy Minister of Ecosystems and Oceans Science at DFO, specified that although the Deputy Minister is responsible for the overall application of the Policy on Science Integrity, the Ombudsperson is responsible for managing any allegations of policy breaches.[10]

Different policies and guidelines based on the Policy on Science Integrity, such as the Policy on Conflict of Interest in Science Peer Review Processes and the Policy on Participation in Science Peer Review Meetings, are followed during the CSAS process. However, the Committee heard many witnesses describe elements of CSAS processes as problematic. They described the long delays encountered before getting a report on the detection of Piscine orthoreovirus (PRV) in farmed Chinook salmon published because of a disagreement between industry veterinarians and DFO staff on the interpretation of the data, the inclusion of particular interest groups in the CSAS process, and the use of consensus during the CSAS process as a suppression tactic. These examples are discussed in further detail later in this report.

Communication of Scientific Information and Advice

Upon completion and approval, all CSAS process documents are to be made public on the CSAS website in accordance with DFO’s Policy on Distribution of Publications. CSAS publications include:

- Research documents, which contain the supporting scientific information and analyses needed to generate advice;

- Science advisory reports, which contain scientific advice and outline the uncertainties and limitations of the advice;

- Proceedings, which document the discussions held during the peer review process and include a list of internal and external participants; and

- Science responses, which document the peer-reviewed scientific advice and proceedings for urgent and unforeseen requests for information or advice following the Science Special Response Process.[11]

While DFO recognizes the role of researchers and scientists in communicating information to the public, the Policy on Science Integrity states that there may be “legitimate and compelling reasons that may limit the disclosure or availability of research or scientific information to employees, stakeholders or the public.”[12] Examples of legitimate and compelling reasons given by the policy include “the need for caution and prudence in the public communication of classified or sensitive scientific or research information, as well as existing legal constraints on information disclosure”.[13] However, the policy also mentions that DFO researchers and scientists “have the right, and are encouraged, to speak about or otherwise express themselves on science and their research without approval or pre-approval [from their managers or supervisors] and without being designated as an official spokesperson.”[14]

Ministerial Decision-Making for Fisheries Management

Although ministerial decisions may be informed by science advice, pursuant to section 2.5 of the Fisheries Act, the Minister may also consider factors such as community knowledge, Indigenous knowledge, and social, economic, and cultural issues.[15] Ministerial decisions must, however, respect conservation principles, legally-binding agreements, and Aboriginal rights and treaty rights.[16] Regarding fisheries management, the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard, pursuant to the Fisheries Act, has the authority to determine, among other responsibilities:

- the annual total allowable catch (TAC) of a species or stock;

- fisheries licence conditions;

- the times and seasons for fishing; and

- restrictions to be imposed (e.g., gear type, dockside or at-sea monitoring, reporting requirements).

Bernard Vigneault, Director General of the Ecosystem Science Directorate at DFO, summarized the production of science advice at DFO as follows:

As a science-based department, science integrity is essential to the work of the department and its employees. Science integrity is critical to the decision-making process, from the planning and conduct of research to the production and the application of advice. Departmental scientists are bound by our code of ethics and values, and our science integrity policy, which reinforces principles such as transparency, scientific excellence and ensuring high standards of research ethics.

DFO generates science advice in a transparent way, using the Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, which is based on the principle of evidence-based peer review. Participants in the peer review process participate as objective experts to complete the peer review of the science under consideration. To guide participation, DFO has published a conflict of interest policy and a policy on participation for the CSAS meetings.[17]

During the study, witnesses described various stages during the development of advice for decision-makers where scientific information could be blocked or modified, such as during the CSAS process or as the information was being prepared to be communicated to the Minister. For example, Alexandra Morton, Independent Scientist (as an individual), described a situation where DFO management briefed representatives of the aquaculture industry but did not brief the Minister about the risk posed to young Fraser sockeye by Tenacibaculum maritimum after having been alerted to the risk by DFO scientists.[18] Robert Chamberlin, chairman of the First Nations Wild Salmon Alliance, believed that the aquaculture industry had been much too involved in the CSAS process related to open-net cage fish farms for it to be objective.[19] Witnesses also described issues with DFO’s data collection, which is the foundation for all the department’s science advice.

The Collection of Scientific Data and the Production of Scientific Products by Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Bernard Vigneault described the collection of scientific data and the production of scientific products at DFO as follows:

Each year, DFO science mobilizes teams of research scientists, biologists and technicians to conduct field and laboratory studies for hundreds of distinct projects in marine and freshwater systems. This results in a wealth of knowledge about our ecosystems and fish populations to support the departmental decision-making. The science sector has expertise in a wide range of fields, including marine environment and aquatic ecosystems, hydrography, oceanography, fisheries, aquaculture and biotechnology. DFO science is made up of science professionals located in research institutes, laboratories, experimental centres and offices across the country. Science staff collect data and conduct research and monitoring activities, the results of which contribute to the science advice that can be used to answer specific questions or to inform decisions.[20]

DFO uses an ecosystem science approach. Greig Oldford, PhD Candidate and Scientist at the University of British Columbia (as an individual), defines this approach “as a broad approach to studying relationships and interactions in the ecosystem, and it integrates science outputs. We prioritize and try to understand the key relationships in nature and their links to human needs and management actions.”[21] Dominique Robert recommended accelerating the implementation of an ecosystem approach to fisheries management in Canada, noting that a 2019 CSAS report concluded that less than half of the 178 stock assessments reviewed considered ecosystem aspects.[22] He believed that if “we want to offer better scientific advice with an ecosystem approach to management, but there is a lack of certain crucial components of the ecosystem, such as forage species, it will be difficult to achieve this.”[23] Keith Sullivan, President of Fish, Food and Allied Workers - Unifor, agreed that the use of an ecosystem approach was appropriate but emphasized the need to consider all elements of the ecosystem, including predators such as seals.[24] Mona Nemer explained that climate change is changing different conditions in the ocean, including the temperature, salinity and acidity of the water.[25] Dominique Robert believed the “rapid ecosystem changes we are currently experiencing because of global warming also require the consideration of ecosystem variables in stock assessments to ensure sustainable management of our resources.”[26]

Recommendation 1

That the Ocean science activities of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) prioritize a comprehensive research strategy to determine the current and estimated future impacts of climate change on marine life and provide regular public updates on findings.

Recommendation 2

That the Government of Canada request that the Chief Science Advisor examine how and to what degree DFO has deployed an ecosystem-based approach for stock management and recovery, and, if necessary, make recommendations on how DFO may better implement ecosystem-based fisheries management.

Recommendation 3

That DFO speed up the implementation of an ecosystem-based approach to fisheries management in Canada given the impact of climate change.

Witnesses mentioned the importance of cooperation within the federal government as well as with different stakeholder groups and associations, including industry, Indigenous groups, universities and citizen anglers, to maximize the data available. Jean Côté, Scientific Director at the Regroupement des pêcheurs professionnels du sud de la Gaspésie, described the Lobster Group (or Lobster Node) as “a group of fishers’ associations from the five Atlantic provinces. Government researchers from DFO, a provincial ministry, as well as university researchers” that “conducts studies and fills the gaps in our knowledge about the productivity, structure and connectivity of lobster stocks in their distribution area” through collaborative study.[27] Andrew Trites believed a “collaborative research program overseen by fishermen, academics and government scientists,” such as the Canadian Fisheries Research Network which existed between 2010 and 2015, would be a good way to address many of the concerns raised about science at DFO.[28] Brian E. Riddell, Science Advisor at the Pacific Salmon Foundation, reminded the Committee that citizen science can be a powerful data collection tool.[29] Witnesses also mentioned the importance of collaborating with the United States when working on transboundary species such as wild Pacific salmon or Atlantic mackerel.[30]

Recommendation 4

That Canada increase collaboration with our international allies and neighbors for stock assessments and scientific research for all transboundary species.

Kathryn Moran, President and Chief Executive Officer at Ocean Networks Canada, described the Sea Grant program in the United States where regional funding is directed towards the interests of fishers and the “science they need to help them advance their economic benefit.”[31] She suggested this could be a model to consider in Canada.

Dr. Kristi Miller-Saunders explained that funding within DFO is “largely based on competitive proposals.”[32] She told the Committee that she anticipated funding under the Pacific Salmon Strategy Initiative but had yet to receive any. Her research program on pathogens, environmental stress and climate change is funded “principally through money [from] outside of the department” because of better success in generating funds to do the research with outside granting agencies than from within DFO.[33]

Recommendation 5

That the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard direct departmental officials to immediately initiate a review of DFO allocations for science to ensure departmental resources are available for the scientific work in both fisheries and ocean science that is required to inform decisions of DFO and Minister and likewise ensure that DFO scientists are not dependant on external funding streams to complete their work.

Stock Assessments

In fisheries management, the precautionary approach means “being cautious when scientific information is uncertain, unreliable or inadequate and not using the absence of adequate scientific information as a reason to postpone or fail to take action to avoid serious harm to the resource.”[34] Sufficient and timely data is therefore important because the quality of recommendations made to decision-makers depends on the data available. Robert Chamberlin believed the precautionary approach requires the removal of fish farms from coastal British Columbia.[35]

Witnesses expressed concern that a lack of capacity and resources within DFO, as well as competing priorities between oceans and fisheries sciences, could mean that some stock assessments or surveys cannot be completed in a timely manner. Adam Burns, Acting Assistant Deputy Minister of Fisheries and Harbour Management at DFO, stated that decisions for stock assessments “are informed by the best available science” even in cases when the science might have been done prior to the year in question.[36] According to Christina Burridge, Executive Director at the BC Seafood Alliance, if stock assessments are not timely, “TACs may be more precautionary than necessary, meaning benefits to Canadians are constrained.”[37] Kris Vascotto, Executive Director of the Atlantic Groundfish Council and Carey Bonnell, Vice-President, Sustainability and Engagement at Ocean Choice International L.P., expressed dismay at delayed stock assessments.[38]

Given the “ongoing challenges in most DFO regions in getting the science programs delivered,” Morley Knight, retired Assistant Deputy Minister of Fisheries Policy at DFO (as an individual), believed that “[t]hose responsible should be held accountable to make sure that the surveys are done and that DFO science gets top priority. When it doesn't get delivered, those who were responsible should be held accountable.”[39]

Charlotte K. Whitney, Program Director of Fisheries Management and Science at the Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance, questioned how DFO prioritizes stock assessments given that “many targeted and bycatch stocks have outdated assessments or no assessment at all.”[40] Given that 80% of stocks have no fishing mortality estimates, Robert Rangeley, Director of Science at Oceana Canada, hoped that DFO would address inconsistencies in catch monitoring by fully implementing the fishery monitoring policy.[41]

Christopher Jones, retired Senior Fisheries Manager at DFO (as an individual), explained that in the Maritimes region, scientific effort had been focused on certain high-profile stocks such as crab, lobster and halibut because of limited resources. Fisheries that are not high profile receive “very little to practically no science support” in the two-tier system.[42] Dominique Robert explained that, more generally,

the quality of available data varies greatly between stocks. The assessment of some historically and culturally important species, such as Atlantic cod in eastern Canada, relies on high quality data from multiple sources. Other stocks, however, such as forage species, are data poor. Basic measures, such as their spawning biomass, are sometimes unknown. The quality of the recommendations that scientists can make is therefore directly dependent on the data available.[43]

Morley Knight believed that when there is greater uncertainty about the status of a particular stock, “there has to be a redoubling of efforts to find out the real truth and be more certain about what the real situation is.”[44] He suggested that could be the case with the Atlantic mackerel.

Melanie Giffin, Marine Biologist and Program Planner at the Prince Edward Island Fishermen's Association, emphasized that the collection of field and at-sea data necessary for stock assessments is crucial and that funding for these activities must be ensured. She suggested that this data could be collected by DFO or by industry on behalf of DFO.[45] Kathryn Moran suggested that DFO could make use of autonomous surface vehicles to complete stock assessments.[46]

Dominique Robert believed that a limitation for collecting new data is aging Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) vessels, which are already in such high demand for existing surveys that finding the time to repair them is difficult.[47] Kris Vascotto and Carey Bonnell agreed and suggested that more resources be directed to this issue.[48] Arran McPherson told the Committee that three new dedicated CCG fisheries vessels have recently transitioned into service.[49]

Recommendation 6

That DFO conduct an internal audit on the performance of new research vessels to ensure the suitability of new vessels to maintain and improve the DFO’s ability to conduct stock assessments, and that the results of this audit be communicated to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans.

Witnesses also discussed the ability of departmental officials to complete all the required data analysis. Kris Vascotto worried “[r]ecent staffing efforts focused on populating new programs have resulted in a drain from existing ones. This means more vacancies in key stock assessment positions and gaps in analytical capacity.”[50] Robert Rangely suggested that DFO might have a difficult time meeting the timelines of Canada’s new stock rebuilding regulations.[51] Christopher Jones wondered what impact the attribution of physical and human resources to monitoring protected areas would have on the department’s ability to undertake stock assessments.[52] Christina Burridge worried that stock assessments necessary to meet the conditions necessary to obtain a Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certification could be delayed in favour of regulatory or legislative requirements, such as those under the Species at Risk Act, due to a lack of sufficient staff.[53] The Fisheries Council of Canada stated in its brief that delays in stock assessments can lead to fisheries losing their MSC certifications.[54] Kris Vascotto emphasized the importance of mentorship opportunities for newer staff within DFO as well as staff retention policies to develop and keep stock assessment knowledge within the department.[55]

Carey Bonnell expressed concern that, “even though demands for government-required rebuilding plans, as well as sustainability certification supports” have grown in the last few years, recent investments in DFO science

have primarily been to support ocean science—such as funding to support marine conservation targets, marine mammal research, etc.—as opposed to its capacity and expertise for commercial stock assessments. While investment in ocean science is critical to monitor the health of our oceans, it is high-quality stock assessment science that ensures the sustainable and optimal utilization of Canada's fish stocks.[56]

Martin Mallet, Executive Director of the Maritime Fishermen's Union, suggested that DFO stock assessments be adapted and properly funded to reflect a “rapidly changing ecosystem associated with climate change.”[57]

Recommendation 7

That DFO allocate sufficient resources, including sufficient at-sea capabilities, to conduct timely and comprehensive stock assessments and acoustic surveys for all commercial fish species.

Recommendation 8

Considering that DFO’s scientific models used for stock assessments rely on data from surveys, the Committee recommends that greater emphasis be placed on completing surveys and robust data acquisition, even when vessels break down or are unavailable. That DFO do this by fostering relationships with the fishing industry to utilize commercial fishing license holders and vessels to supplement DFO scientific data collection.

Recommendation 9

That, in order to ensure stock assessment surveys are completed, DFO identify and use opportunities that exist for harvester data to be included in stock assessment activities, thereby contributing to collaborative and citizen science.

Recommendation 10

That DFO immediately implement, in partnership with academic and industry scientists, a review of the criteria for the selection of survey areas to consider variability in stock distributions as well as harvester observations in order to have a more realistic view of the status of fish stocks and fishing pressure. These stock surveys should take place twice a year.

Recommendation 11

Given the importance of a sustainable fishery on the economic and social health of small, coastal communities and our obligations toward Indigenous reconciliation, that DFO prioritize completing regular and thorough stock assessments on all three coasts and commit to timely and fulsome community and stakeholder engagement on proposed fishing restrictions to protect fish stocks and marine species threatened or at risk.

Recommendation 12

That DFO commit to more timely decision‑making to provide certainty to fish harvesters and industries impacted by fisheries decisions. This would ensure that those impacted, whether positively or negatively by these decisions have enough time to prepare and react to the changes and will ensure that government can provide support for those industries negatively impacted by fishery closures.

Recommendation 13

That DFO review the allocation of its resources, financial and otherwise, between ocean science and fisheries science to

- ensure sufficient funding for the stock assessments required for sound management, eco certifications and rebuilding plans required to restore depleted stocks; and

- reflect the commercial, social, and cultural importance of fisheries in coastal communities.

Recommendation 14

That DFO introduce an annual Report to Parliament on the status of fish stocks, staffing levels and expenditures by program area, and fisheries management performance in a publicly available report to enable transparency of evidence used for ministerial decision-making, including any pertinent decision notes.

Recommendation 15

That the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard immediately direct departmental officials to provide the Committee on an annual and ongoing basis with documentation containing tables reflecting how many fishery stocks DFO manages, how many stocks have and have not been assessed in the current year, and what actions the Minister will commit to ensure resources and direction are provided to increase stock assessments starting in 2023 as an annual exercise.

Modelling

Greig Oldford told the Committee that “simulation modelling and computer modelling [do] play an outsized role in marine ecology.”[58] He added that it isn’t easy to navigate uncertainty in modelling, especially in marine ecology since variables can’t be isolated in controlled experiments and long-term data series are not always available.[59] Andrew Trites explained that an aspect of modelling that is often overlooked is the degree of certainty of a model (i.e., how likely a particular outcome is). He added that a higher certainty (such as 80%) is likely preferred for big decisions and that a lower certainty (say 30% to 40%) could be enough for decisions where what is at stake is not considered to be of high value.[60]

Christopher Jones told the Committee that over the past several years, it seemed as though “DFO has updated most of its stock assessment models, which for the most part have resulted in decreasing assessments.”[61] He wondered why the models had been updated at this time, if the models were updated to take an approach more focused on conservation, which parameters had been updated and to what extent, and whether the models had been modified to more closely resemble Scandinavian stock assessment models. He described the impact of the new model on the halibut stock assessment, a fishery that “has been solid on the Atlantic coast for years,” as follows:

The population has recovered under the existing models. This has created questions. If the existing model was either inadequate or flawed, how could the halibut population thrive using it? What was the rationale for changing the model if the model may not have been flawed? The new model suggests reducing the quota by 13%. Is this an indicator of increased accuracy within the new model, or has the model been adjusted to reflect the enhanced conservation objectives? If not, is there an accuracy threshold that the new assessment modelling is striving to achieve?[62]

Jesse Zeman, Executive Director, B.C. Wildlife Federation, described how DFO management, not DFO science, developed a model for the period where interior Fraser steelhead move through the Fraser River. While this model “was rejected through the peer review process,” Mr. Zeman stated that “DFO management is still using this rejected model to brief the minister.”[63]

Jean Côté told the Committee about to a novel artificial intelligence model that uses “post-season data collected over the last 10 years to predict the evolution of stocks and catches” that his organization had developed with a private company rather than in collaboration with DFO because of a lack of availability from the relevant DFO official.[64]

Recommendation 16

That the current DFO modelling used for stock assessments be changed to allow for fisher data input and that the DFO modelling should be reviewed in the European stock assessment modelling concept.

The Development of Science Advice through the Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat

The Committee heard many witnesses describe what they believed were shortcomings within the CSAS process, including potential conflicts of interest for participants to the CSAS process and the use of consensus to stifle opposing views. Witnesses including Jeffery Young, Senior Science and Policy Analyst at the David Suzuki Foundation, Greg Taylor, Consultant and Fisheries Advisor at the Watershed Watch Salmon Society, and Andrew Bateman told the Committee that DFO’s processes are good in theory but not in practice.[65] Robert Chamberlin suggested that “CSAS is a shining example of the environment within DFO that needs to be meticulously analyzed and restored back to its original mandate—namely, the mandate of actually working to protect the environment and wild fish for Canadians.”[66] Jeffery Young stated that “the process for DFO decision-making is broken, and science is at the middle of this failure, or, more concerningly, is being pushed to the side.”[67]

While most witnesses agreed that there were issues with at least some elements of the CSAS process, they suggested differing levels of necessary intervention. Alexandra Morton suggested the formation of a “a non-government board of scientists to monitor DFO's response to science.”[68] John Reynolds suggested that DFO could “adopt a prime directive where management objectives are expressly prohibited from influencing science, and there could be checks and balances along the way to ensure that is occurring.”[69] Jesse Zeman proposed a “full restart” in order to “separate DFO management from DFO science.”[70]

Composition of Groups Involved in Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Processes

DFO’s Policy on Conflict of Interest in Science Peer Review Processes was implemented in 2021. The policy “directly addresses the importance of objective science, free from political, commercial and client interference.”[71] According to Arran McPherson, who is the DFO official responsible for the policy, the conflict of interest policy “codified what was already a best practice in many of our CSAS processes across the country, and codified that participants who come to our meetings are in fact there as impartial experts bringing their expertise and not a consideration of the impacts of decisions.”[72] She further explained that the chair of individual CSAS processes is “responsible for ensuring that the conflict of interest policies are respected throughout the process.”[73] Bernard Vigneault described peer review as a “vital component of the important challenge function that the DFO science sector provides” with the objective of providing “sound, objective and impartial science information and advice.”[74]

Witnesses expressed apprehension about the composition of some the panels and tables in CSAS processes, worrying that the presence of a particular interest group could skew the conclusions reached. For example, Keith Sullivan, Martin Mallet, Jean Lanteigne, Director General of the Fédération régionale acadienne des pêcheurs professionnels, and Kris Vascotto spoke of the presence of environmental non-governmental organizations at fisheries advisory tables.[75] Various witnesses also spoke about the presence of the fish farming industry during CSAS processes related to aquaculture and wild Pacific salmon. These examples are presented in an upcoming section.

Jeffery Young proposed that “[s]takeholder tables and even technical working groups formed by DFO have largely served to reposition DFO as an arbiter between interests rather than a regulator and upholder of good science and evidence-based information.”[76]

However, not all the witnesses believed that undue influence was being exerted by participants in CSAS processes. The experience of Josh Korman, Fisheries Scientist at Ecometric Research Inc., with the CSAS process led him to believe that the review process of working papers is actually “quite rigorous,” and he had “not observed that unsupported bias from DFO fisheries management or outside parties have unduly influenced CSAS working papers or their final versions.”[77]

Recommendation 17

That DFO conduct robust peer reviewed, non-biased science with academic organizations and include both harvesters’ knowledge and Indigenous traditional knowledge.

Recommendation 18

That the Government of Canada initiate an independent audit of how and to what degree DFO has implemented their science integrity policy and that the resulting audit report be tabled in the House of Commons in 2023.

Use of Consensus during the Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Process

Regarding the consensus needed to formulate science advice during the CSAS process, DFO documentation notes that:

[i]n cases where there are two or more equally reasonable conclusions, the peer review may apply a “weight of evidence” approach to clarify which is most strongly backed by current available scientific evidence. Strongly opposing opinions or viewpoints may be noted in the record of proceedings.[78]

Witnesses who had participated in CSAS meetings questioned the atmosphere at these meetings. Michael Dadswell, retired professor of biology at Acadia University (as an individual) shared that, based on his experience at more than 20 CSAS meetings, “differing opinions on data and conclusions that are contradictory to DFO policy and unsanctioned by CSAS are most often totally unwelcome and usually ignored.”[79] Andrew Bateman explained that “consensus is held up as a strength of CSAS, but meetings apply strong social pressure on dissenting voices […]. There is no mechanism for errors to be addressed once the consensus box has been ticked.”[80] He added that:

In any case, consensus is not a requirement of the scientific process, and the practice of minimizing real disagreement does a disservice to decision-makers and flies in the face of the SAGE guidelines that state that decision-makers should consider the multiple viewpoints received, not just the distilled version of uncertainty used in practice.[81]

Brian Riddell, Science Advisor at the Pacific Salmon Foundation, argued that forcing consensus was a disservice to the Minister since they have “the responsibility to understand the uncertainties, as well. That’s where the management of policy comes into play, not in the science.”[82]

Arran McPherson clarified that DFO defines consensus as “‘absence of evidence-based opposition'. It's not enough to disagree. There needs to be evidence that's brought forward to support the point of view that's being made at the meeting itself.” She added that the possibility to make note of “perspectives or issues that did not arrive at consensus” does exist within the CSAS process and is left to the discretion of the chair. She explained that it was an element that could be used more often.[83]

Examples of the use of consensus during the CSAS process in the context of wild Pacific salmon are discussed in an upcoming section.

Transparency and Communication of Scientific Information

Bernard Vigneault stated that the results of peer reviews and the supporting analyses are

published on the department's website. These scientific analyses inform departmental decision-making and provide Canadians with the scientific analyses and advice generated by the departmental science staff. DFO also supports open science, has an action plan and continues to publish data, including through the open government data portals. All DFO science reports are open and accessible.[84]

Jeffery Young described the importance of the transparent scientific communication as follows:

Our challenge today is a lack of accountability built on a foundation of transparent, evidence-based reporting. Science needs to be recentred in the decision-making structure, while we ensure that it is adequately transparent and independent of political interference. It is appropriate for the political decision-makers to weigh multiple considerations, but it is critical that science advice and information be as objective as possible and be made available to the public.[85]

Witnesses were dissatisfied with the amount of publicly available information. Robert Rangely told the Committee that less than 10% of science publications are released on time despite the CSAS policy to “ensure transparency and timely dissemination of publications.” He added that

the most relevant science advice was often not publicly available until after the decision was made and communicated. As a result, and despite the government's intention to promote public transparency and policy engagement, decision-making in DFO may be based too frequently on a flawed or limited understanding of the underlying scientific evidence.[86]

Many witnesses shared examples of scientific information related to wild Pacific salmon seemingly being suppressed or altered at different stages of the CSAS process before being communicated to the Minister or made available to the public. Examples of difficulty gaining access to information, apparent changes in research plans to avoid troublesome results and inappropriate interpretation of CSAS documents are presented in an upcoming section.

Recommendation 19

That DFO improve the transparency of data and research by developing a portal to publish the detailed studies, including the scientific and socio-economic impact documentation, that are the inputs into the CSAS and COSEWIC processes. This portal should be easy to navigate and include both raw data and summaries free of scientific or bureaucratic jargon so that all Canadians, and fishers in particular, can understand the findings.

Recommendation 20

Make all scientific data produced by DFO publicly available for peer review from researchers outside of the Department.

Indigenous Involvement

Aidan Fisher, Biologist at the Lower Fraser Fisheries Alliance, and Greg Taylor described a desire for the increased involvement of Indigenous peoples in the development of scientific conclusions as well as the field and lab work necessary to develop them.[87] Michael Staley, Biologist at the Fraser Salmon Management Council, explained that support to develop the scientific and technical capabilities of First Nations would enable them to take up their role in the co-management of fish and fisheries resources with DFO.[88]

Carey Bonnell suggested that Indigenous knowledge and Indigenous stakeholders “deserve a seat at the table, and direct representation and input into the decision-making process.”[89]

The role of Indigenous knowledge in the development of science advice was discussed. Witnesses expressed hope that traditional knowledge would be better incorporated into DFO’s scientific activities and conclusions. The Committee heard that it is currently only applied as a small part of the peer review process and often not applied in the final recommendations. Charlotte K. Whitney explained that “Indigenous knowledge often has longer baselines and superior understanding of local ecosystems than western science does and, therefore, should be treated as the valid knowledge system that it is.”[90]

Alejandro Frid, Science Coordinator at the Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance, gave the Committee an example of the longer baselines of Indigenous knowledge and how they can benefit the development of science advice. He described an analysis of data that showed “very rapid declines in the size and age structure of yelloweye rockfish.”[91] The DFO survey data from 2003 to 2015 showed a “decline of about half a centimetre per year in the average size of yelloweye rockfish and an average decline of about 10 months per year in the average age of yelloweye rockfish.”[92] Since larger females are more fecund than smaller females per unit of body size, Alejandro Frid explained that this has tremendous implications for fecundity. He further explained that DFO’s data collection started in 2003, after the commercial fisheries had already cause declines in yelloweye rockfish.

Looking at indigenous knowledge through structured interviews, we reconstructed the body sizes of yelloweye going back to the 1950s or so and how, in the catches of indigenous fishers, those sizes changed over time. Between 1980—which is before any of these scientific surveys had begun—and 2000, we see a decline of nearly half the average size. If we only look at the scientific data, we will have a shifting baseline of what would have been considered normal. It would be starting in 2003, which is about half the body size and disproportionally lower fecundity that was there before the commercial fisheries got under way.[93]

Robert Chamberlin emphasized that Indigenous rights are not site-specific, giving the example of the impacts fish farms in the Discovery Islands have on Pacific wild salmon that migrate past them and into the interior of British Columbia.[94]

Recommendation 21

That the government expand the CSAS process beyond scientists and individuals with a scientific background to be more inclusive of traditional Indigenous knowledge and harvesters’ knowledge.

Recommendation 22

That DFO work to incorporate traditional Indigenous knowledge and fisher knowledge into its scientific activities and to give it greater consideration.

Recommendation 23

That DFO increase the collaborations with Indigenous peoples and fishers in the development of field and lab work, as well as in the development of scientific conclusions.

Recommendation 24

DFO should work with First Nations to develop a culturally appropriate way to use traditional Indigenous knowledge and fisher knowledge in management, such as to trigger early warning signs about the health of marine species and ecosystems.

Recommendation 25

Honour and respect existing fisheries and oceans management cogovernance agreements and implement those processes that are inclusive of Indigenous knowledge, ecosystem and precautionary thresholds.

Recommendation 26

That the government build scientific and technical capacity with First Nations and their organizations in recognition of their inherent Indigenous title and rights.

Industry Involvement

Bernard Vigneault described current interactions between DFO and industry as follows:

We have key collaborations and we consider the information provided by fishers in different ways. It can start from the very beginning. In some cases, we do data collection in partnership with industry, which provides us with samples and participates in sampling. It can also go as far as interpretation and peer review of the data, where we invite industry experts to provide and validate information about fishing activities, observations and methods used.[95]

Matthew Hardy, Regional Director of Science, Gulf Region, DFO, explained that DFO carries out projects in cooperation with industry stakeholders and that “information we derive from industry partnerships is an important factor in many of our assessments.”[96]

Witnesses such as Keith Sullivan, Jean Lanteigne and Martin Mallet believed industry could collaborate more closely with DFO to supplement the department’s ability to collect data.[97] Martin Mallet listed the benefits stemming from a collaborative science process:

[Collaborative science processes] allow fishermen leaders within our membership to understand and buy into the science-backed management measures that are needed to improve our fisheries—for example, lobster and snow crab. For DFO scientists, they enable them to get to know and discuss with fishermen their daily, yearly and even generational observations and insights with regard to ecosystem patterns experienced while fishing. On many occasions, science projects are then developed to test some of these patterns with success. On all occasions, it’s been an opportunity for all parties to exchange, raise awareness on issues and develop trust in a common science process. Where this formula has been used, we have seen success stories such as in the management of the lobster and snow crab fisheries in the southern Gulf of Saint Lawrence. However, with other resources such as herring and mackerel, we are currently facing challenges where this collaboration has not been established or is limited.[98]

Recommendation 27

That DFO should work with fish harvesters to communicate, in a more open and transparent manner their work and scientific conclusions, especially in cases where the evidence seems at odds with the observations of fish harvesters.

Recommendation 28

That DFO make greater efforts to improve the flow of information from fish harvesters to the DFO Science branch about what they are seeing out on the water.

Recommendation 29

That DFO include knowledge and data collected by commercial fishers, including independent inshore fishers, in the peer review process, including their knowledge and observations regarding changes in distribution and abundance. That DFO formalize a system for fishers to participate and provide input in all aspects of fisheries management, including stock assessment protocols and management plans.

Recommendation 30

That DFO apply the same management measures to all fishers of a given species in a given fishing zone based primarily on science and stock conservation for a sustainable fishery.

Industry witnesses expressed a desire for more opportunities for input in the CSAS process. Keith Sullivan was disappointed that a section for harvester or stakeholder observations was removed from the CSAS process.[99] Witnesses such as Jean Côté; Melanie Giffin; Kris Vascotto; Eda Roussel, Fisheries Advisor at the Association des crevettiers acadiens du Golfe; Herb Nash, President of the 4VN Management Board (as an individual); and Leonard LeBlanc, Professional Advisor, Gulf Nova Scotia Fishermen's Coalition, felt that industry knowledge is not given the weight it deserves since harvesters are out on the water and are often the first to see changes.[100]

Christina Burridge described the contribution of industry experts and analysts as bringing “an understanding of fisheries and survey data, assessment methodologies, evaluation, and the management context that scientists may not have.”[101] Jean Côté believed it was one thing to “consult” industry but that “sometimes you have to take our advice and what we say into account.”[102] Christopher Jones added that current DFO consultations assume all fishers are part of an association. He felt that those who aren’t “are discounted, not engaged, not involved and not contacted.”[103]

Recommendation 31

That DFO revitalize relationships with the recreational and commercial fishing industries and demonstrate fair process in decision‑making.

Not all witnesses believed that the involvement of industry should be increased. Robert Chamberlin spoke about the CSAS process for the Discovery Islands risk assessments and stated that a science peer review process that allows a proponent, which is a fish farm company, and industry stakeholders to participate “from the beginning to the end of this process is utterly and completely lacking any measure of objectivity or credibility.”[104] He explained that such situations had led to “CSAS as a peer review secretariat [having] zero credibility with the first nation members of the First Nation Wild Salmon Alliance.”[105]

Role of Science in Decision-Making at Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Mona Nemer explained that science “helps government decision-makers gather data, analyze evidence and assess different policy options and their impacts” and added that “[open] science and transparency are essential not only for creating good policy, but also for maintaining and building trust in our public institutions.”[106]

Greg Taylor believed that the “risk to our fisheries from decisions inconsistent with good science are immeasurably greater” than 40 years ago due to “the climate crisis, cumulative land and water use impacts and a decision-making process that continues to put fisheries before fish.”[107] There was general agreement amongst witnesses that species should be managed in a way that prioritizes the long-term health of a species rather than yearly quotas.

Witnesses spoke about elements of good policy or approaches at DFO that were being incorrectly implemented. Greg Taylor believed Canada has a policy structure in place that would be “extremely effective in turning science advice into good management decisions. It's just that managers have not implemented it.”[108] As an example, he pointed to the Sustainable Fisheries Framework, which provides specific direction to managers but unfortunately “these powerful science-based policies and the management guidance laid out within them are ignored in management decisions.”[109] He added that independent monitoring or oversight could be added to the existing basic structure to ensure it is implemented.

Gideon Mordecai, Research Associate at the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, University of British Columbia (as an individual), argued it was important to focus on “making sure the science information can get to the decision-makers” without information being blocked at any of the various steps in the process.[110]

Greg Taylor mentioned that, contrary to the Constitution of the State of Alaska or the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act in the United States, Canada does not have “an obligation to ensure decisions are consistent with a science-based management framework” and that acknowledging or considering policies is “a far cry from either implementing them or being bound by them as managers are in other jurisdictions such Alaska or the U.S.”[111]

Communication of Science Advice to the Minister

Many witnesses expressed concerns about the scientific advice that was being communicated to the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard; believing that incomplete, modified or misrepresented scientific conclusions may be being provided to the Minister. They believed the advice of competent DFO scientists was being edited along the way to reflect policy preferences. Jesse Zeman stated that his organization was “not concerned with DFO scientists' ability to conduct science. It is concerned with decision-makers and senior managers' willingness to edit, suppress and hide that science.”[112] Josh Korman believed a “sort of firewall […] to confirm that what the science says is translated into the management advice” was needed, sharing that key conclusions from the Recovery Potential Assessment report for interior Fraser steelhead, for which he was the senior author, were not reflected in management advice.[113] Charlotte K. Whitney shared that when disconnects occur between science advice and management decisions, “they have led to management decisions that maintain a status quo rather than applying the best available science.”[114]

Judith Leblanc, Science Advisor at DFO, stated that over her 26 years at DFO, she had learned to accept her “area of influence” and that her duties as science advisor included providing science advice to the department’s management but that once the advice is submitted, the “decisions rest with management,” not with her in her role as science advisor.[115] Dr. Kristi Miller-Saunders agreed and added that “[w]e have very little control or a limited amount of input on what science moves forward to the minister, or even to upper managers in Ottawa, and how they utilize that science.”[116]

Sean Jones, Legal Counsel at Wild First, believed that

DFO managers need to allow scientists to communicate directly with those decision-makers and allow the briefing notes and materials that they prepare to go unadulterated to the minister. We've documented numerous examples where scientists are trying to get critical information to the minister, but DFO managers simply interfere and rewrite the materials, so that the science that is presented is done in a way that confirms existing policy, rather than presenting the minister with the best available information.[117]

He added that DFO would likely see fewer decisions being overturned on judicial reviews if “DFO managers were providing the minister with a more fulsome and objective representation of the evidence before her.”[118]

Examples of situations where peer-reviewed science advice about wild Pacific salmon was seemingly not translated into management advice or not communicated to the Minister is discussed in an upcoming section.

Integration of Fisheries Science and Other Considerations into Fisheries Management Decisions

According to Sessional Paper 8555-431-445, tabled in the House of Commons on 20 July 2020, the CSAS process “explicitly does not consider socioeconomic impacts or the management implications of the advice. The science advice is intended to serve as an input into the decision-making process.”[119] However, some witnesses felt that desired policy outcomes often taint the science advice before it reaches the Minister.

Andrew Bateman believed that science was not the only decision-making factor at the table and that DFO was manipulating science advice. He added that decision-makers

have to weigh competing or complementary demands, the economy being one of them. It's really that the science advice that's presented to the decision-makers, ultimately to the minister, needs to be unfettered by departmental manipulation by mid- and upper-level managers.[120]

Martin Mallet, Keith Sullivan, Martin Paish, Director, Business Development at the Sport Fishing Institute of British Columbia, and Jean Lanteigne agreed that, along with scientific data, social and economic factors should be considered by the Minister as critical components of fishery sustainability.[121] Witnesses underscored the need for transparent and independent scientific advice to be provided to the Minister without it having been tainted by other considerations. John Reynolds, Chair of the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, described such a process:

You can model or advise on what the potential options are and what are mostly likely to be effective. The minister then can take that information about the options and what the science is that is supporting those options, and then bring in these other factors that they have to consider, the trade-offs and the people who will be harmed by the management actions, for example. As long as that’s done in a transparent and open way so that people can see where the science enters and what other factors were being considered, then that would certainly be a process that I think a lot of people could sign up to.[122]

Outside of the CSAS process, DFO does conduct economic analyses to assist departmental decision-makers evaluating the impacts of resource management, policy and regulatory decisions.[123] Witnesses questioned the level of detail within what the department called a socio-economic analysis. Tasha Sutcliffe, Senior Policy Advisor at Ecotrust Canada, suggested that what the department considers a socio-economic analysis is actually a “very shallow economic analysis. It doesn’t go into enough detail on the basic economics around distribution of benefit, coastal community impacts, incomes, for example.”[124] Martin Mallet agreed that “socio-economic science expertise is sorely lacking and is needed more than ever to help us better plan and adapt to [the changes in the ecology, distribution and biomass of several species due to climate change] that are affecting our fisheries and the coastal communities that depend on them.”[125]

Witnesses believed that ignoring early trends and waiting to act risked leading to larger, more drastic actions being required later to protect species. Jean Lanteigne believed that DFO “lets things drag on until its back is against the wall; then it starts asking what it can do. Very often, it ends up closing the fishery because that’s all it can do when things get to that point. That’s no solution.”[126] Dominique Robert gave the example of the Atlantic mackerel commercial and bait fisheries in Quebec and Atlantic Canada being closed with very little warning in 2022 after at least a decade of DFO stock assessments indicating that fishing pressure on the stock was too high, stating that: “It was the right decision to make given the state of the stock, but I think mackerel fishing should have been suspended or severely restricted long before that.”[127]

Recommendation 32

That DFO consult those who could be most socio-economically impacted by its decisions and ensure that the socio-economic impacts on communities and the fishing industry are factored in its decision-making processes. The assessment of economic and social impacts resulting from decisions should be provided when requested by Canadians.

Recommendation 33

That the Government of Canada request that the Chief Science Advisor

- undertake an examination of how DFO fisheries management officials influence the work and findings of DFO scientists; and

- produce a report to government including

- an assessment of such influence,

- whether this influence is appropriate and ethical; and

- recommendations, if necessary, of how to reform fisheries management influence on science in DFO in order to increase independence of DFO science and ensure there is an established conduit for science to be directly channeled from scientists to decision‑makers for them to consider when making decisions.

Recommendation 34

That the Government of Canada request that the Chief Science Advisor

- assess the viability of restructuring existing DFO systems and processes in a manner that would ensure that science advice is independently collated, assessed and delivered to managers and decision-makers by DFO scientists; and

- produce a report with recommendations from this assessment and that that report be tabled by the government in the House of Commons by 2024.

Recommendation 35

That the Government of Canada request that the Chief Science Advisor

- examine to what degree science advice from scientists is implemented in DFO management and decision-making processes; and

- produce a report with advice and recommendations for establishing protocols to measure to what degree science advice from scientists is implemented in DFO management and decision-making processes and that this report be tabled in the House of Commons by 2024.

Recommendation 36

That the Government of Canada develop and table legislation that establishes a science-based fisheries management framework and a requirement for the government, through DFO, to ensure that DFO decisions align with the science-based management framework and demonstrate alignment of decisions with the framework by publicly releasing scientific reasons and other factors for decisions.

Recommendation 37

That the Government of Canada initiate an independent audit of how and to what degree DFO has implemented the Sustainable Fisheries Framework and that the resulting audit report be tabled in the House of Commons by December 15, 2023.

Recommendation 38

That the Government of Canada request that the Chief Science Advisor

- assess the viability of establishing an independent science advice body to directly advise DFO decision-makers, assess health and performances of fisheries, make recommendations on scientific research priorities, and oversee the implementation of science-based activities; and

- provide this assessment in a report with recommendations to the government to be tabled by 2024.

Need for and Use of Science in Relation to Particular Species

Witnesses shared examples where they felt scientific conclusions had been suppressed or modified before reaching the Minister or where the decisions taken seemed counter to scientific advice or data. For example:

- Greg Taylor described the “arbitrary decision to cut in half the harvest of herring on the west coast” in 2022, even though the fishery had been managed in a way that was consistent with both science advice and policy up until that point.[128]

- Charlotte K. Whitney wondered why the TAC for Bocaccio, a Pacific rockfish, was increased 24-fold from 75 tonnes to 1,800 tonnes based on an unusually strong recruitment event in 2016.[129]

- Jean Côté described a second commercial lobster fishing season opened in 2020, ostensibly to collect data, in Lobster Fishing Area 21 that seemed counter to recent DFO science advice that “in the context of environmental change, inducing a new source of variability is undesirable.”[130]

- Phil Morlock, Director, Government Affairs at the Canadian Sportfishing Industry Association, stated that “official DFO policy” seemed to have become “[a]rbitrary public access closures by percentage targets with no basis in science or evidence of benefit.”[131]

Witnesses also told the Committee about situations where they believed more data was needed or that data appeared to have been ignored. For example:

- Eda Roussel suggested more data was needed to understand the impact of rockfish predation on shrimp.[132]

- Keith Sullivan expressed frustration at the recent closure of the Atlantic mackerel fishery despite repeated proposals to study harvesters’ observations of small mackerel that were likely not born in the Gulf of St. Lawrence: “It's really disappointing when a result ends up in a moratorium and you believe there are people thrown out of work, when there are questions that could have been answered.”[133] Melanie Giffin suggested that standardized voluntary logbooks could be a way to record the small mackerel currently being anecdotally reported in Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland. The information could then be forwarded to DFO.[134]

- Martin Mallet described a roughshod protocol developed quickly with DFO to collect data on the spring herring fishery, after the closure of the fishery led to the loss of access to data previously collected by harvesters.[135]

Two specific examples are described in more detail below.

Example: The Impact of Pinnipeds on Various Fish Stocks

Witnesses discussed the impact of increasing pinniped populations on various fish stocks, including West and East coast salmon, mackerel, herring, capelin, Atlantic cod and Atlantic mackerel. Keith Sullivan questioned if fishing quotas could ever be reduced enough to lead to a rebuilding of stocks if increasing pinniped populations consume more than the quotas themselves.[136] Robert Hardy, Fisheries Consultant, stated that DFO Science is reluctant to accept the impact of seals on any fish stocks, and instead remains dismissive and ignores the evidence provided by fishers, Indigenous peoples, industry associations and seal science from other North Atlantic fishing nations.[137]

Josh Korman described to the Committee how the main conclusions of the Science Advisory Report (SAR) for interior Fraser steelhead were not consistent with the main findings of the Recovery Potential Assessment report, which was developed in a peer-reviewed CSAS process. A main conclusion of the Recovery Potential Assessment report was that

reductions in the abundance of seals and sea lions was deemed to be the most effective way of recovering steelhead populations. This fundamental conclusion was substantially altered by DFO when they wrote the SAR. For example, they stated there was no consensus that there was a causal relationship between the two—meaning a relation between steelhead and seals and sea lions.[138]

Josh Korman did not recall hearing any substantiated objections to the conclusions that reducing pinniped abundance is the most effect way to recovering steelhead populations but could not document the discrepancy because the proceedings of the CSAS process are not publicly available. He believed this misrepresentation was problematic because it “misrepresents the primary tool available to us to improve the status of interior Fraser steelhead and likely for chinook and other salmon.”[139]

Keith Sullivan, Robert Hardy, and Leonard LeBlanc expressed the desire to include the fishing industry and local communities in plans to establish a market for seal products.[140] Mark Prevost, President of Bait Masters Inc., believed that a potential use for seal byproducts could be as an ingredient in alternative bait sausages for the crustacean fishery.[141]

Other witnesses expressed caution at the idea of managing pinniped populations as a way of increasing the number of fish available for fishers. Jeffery Young mentioned that the removal of predators such as pinnipeds could have unexpected and unpredictable impacts on the ecosystem.[142] Alexandra Morton explained that seals and sea lions prey on hake which consume juvenile salmon. A reduced pinniped population could mean a larger hake population and stronger hake predation on juvenile salmon.[143]

Recommendation 39

That scientists conduct pinniped diet analysis for all species of pinnipeds over longer periods of the year in more diverse regions than in the past and make their data publicly available by posting it on the DFO website.

Recommendation 40

That, in order to accurately assess the effects of pinniped predation when estimating mortality levels in fish stock biomass, scientists compare data from countries with similar species of pinnipeds.

Example: Aquaculture and Wild Pacific Salmon

Witnesses told the Committee about different situations related to wild Pacific salmon that illustrate many of the different issues described with the CSAS process including conflicts of interest for participants and the inappropriate use of consensus. They also told the Committee about problems with transparency and the communication of scientific information to the public and with the communication of science advice to the Minister. Jesse Zeman summarized the situation as follows: “When there is good science and it affects DFO management, that science is hidden or edited or suppressed from Canadians.”[144]

Additionally, witnesses frequently mentioned the apparent conflict of interest within DFO between its mandate to protect aquatic species and its mandate to regulate and promote aquaculture. Alexandra Morton did not understand why there was a “big, aggressive, powerful aquaculture management division in DFO and nothing to counterbalance it with the wild salmon […] Aquaculture is thriving. Wild salmon are collapsing. It's pretty clear that they need advocates within DFO.”[145] She gave the example of a situation where industry communicated to DFO that proposed aquaculture conditions of license related to the limit of sea lice per farmed salmon

“could have significant impact on... the... financial performance of Mowi's operations”. Specifically mentioning sea lice, they say that the pace of “regulatory change is outpacing our company's capacity.” Two weeks later, the draft conditions of licence contained the weakened requirement to produce a plan to reduce sea lice, with no requirement that the plan was actually successful.[146]

Sean Jones and Alexandra Morton believed that an independent scientific advisor should be appointed to advise the Minister on scientific evidence related to the impacts of aquaculture on wild Pacific salmon.[147]

Rebecca Reid, Regional Director General of DFO’s Pacific Region, explained that the regional director in the Pacific region is responsible for the management of all fisheries in the Pacific region as well as for aquaculture.[148] She believed DFO understands its role and responsibilities for the management of wild salmon and aquaculture and does so appropriately. Sarah Murdoch, Senior Director of Pacific Salmon Strategy Transformation at DFO, described a new group launched at DFO through the Pacific Salmon Strategy Initiative that works with “colleagues and representatives from branches throughout the department that do salmon work, whether that be salmon science, fish management, enforcement or salmon enhancement.”[149]

Recommendation 41

Given the conflict of interest between DFO’s mandate relating to aquaculture versus the application of the precautionary principle and the ongoing crisis for the health of wild Pacific salmon stocks, that the government implement, on the West Coast only, Recommendation #3 in the Cohen Commission report on the state of wild salmon:

- “The Government of Canada should remove from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans’ mandate the promotion of salmon farming as an industry and farmed salmon as a product.”

Recommendation 42

That the Government of Canada initiate an independent audit of what recommendations of the December 2018 report titled “Report of the Independent Expert Panel on Aquaculture Science” have been implemented by DFO, how many have been fully implemented and timelines for full implementation for recommendations that are not yet fully implemented and that the resulting audit report be tabled in the House of Commons by June 9, 2023.

Recommendation 43

That, in light of the established aquaculture management division within the department and that DFO favours the interest of the salmon-farming industry over the health of wild fish stocks, DFO establish a wild salmon position independent from this division as recommended in Recommendation 4 of the Cohen Commission report to maintain impartiality.

Recommendation 44

That DFO place appropriate and adequate value to perspectives provided by the External Advisory Committee on Aquaculture Science, and reflect such perspectives in policy recommendations and advice to the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard, and that the work of the External Advisory Committee on Aquaculture Science be reported to Parliament on an annual basis.

Conflict of Interest for Participants in Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Processes related to Pacific Salmon

Gideon Mordecai spoke about the presence of the salmon farming industry during CSAS assessments of the impacts of PRV on wild Pacific salmon, stating that “[n]ormally in science, reviewers who have a conflict of interest are often excluded, especially if the conflict is financial.”[150] Sean Jones agreed since “industry licensees were asked to vote on how to diagnose a disease that, if diagnosed, would create significant regulatory burdens on their operations.”[151]

Andrew Bateman described the CSAS processes for the Discovery Island risk assessments in which he participated as follows:

The processes were neither unbiased nor independent. The risk assessments were implemented, closely managed and influenced by senior officials from DFO aquaculture, and employees, contractors and others linked to the salmon farming industry served on the steering committee and as senior reviewers, so that conflict of interest threatened the integrity of the process.[152]

Use of Consensus in Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Processes related to Pacific Salmon

In the context of the assessment of the risk to Fraser River sockeye salmon due to the transfer of Tenacibaculum maritimum from Atlantic Salmon farms in the Discovery Islands area, Andrew Bateman felt that “dissenting voices were all but bulldozed, such that the resulting advice document doesn’t reflect the true reality of opinion.”[153] He added that, for the Discovery Island risk assessments as a whole, the “findings of minimal risk reflect neither the current state of knowledge nor true scientific consensus. Key risks were omitted. Sea lice, cumulative effects and the conservation status of the sockeye stocks were ignored.”[154]

Transparency and Communication of Scientific Information related to Pacific Salmon

Gideon Mordecai, Alexandra Morton, and others believed the impacts of PRV and Tenacibaculum maritimum on Pacific wild salmon were being minimized by DFO in favour of the aquaculture industry.[155] Sean Jones agreed, sharing that his experiences had convinced him that:

[T]he aquaculture management directorate and the Canadian science advisory secretariat consistently suppress, misrepresent and ignore the scientific evidence demonstrating that open net-pen feedlots of Atlantic salmon threaten the survival of wild Pacific salmon. DFO relies on this suppression and misrepresentation to excuse itself from executing its legal obligations, both domestically and internationally.[156]

Stan Proboszcz, Senior Scientist at the Watershed Watch Salmon Society, believed that DFO may have decided to complete only nine risk assessments for aquaculture operations in the Discovery Islands area and not a 10th risk assessment on the effects of sea lice on sockeye salmon to avoid publicizing inconvenient research. Initial lab studies on the effects of sea lice on sockeye salmon

turned out to be quite significant in showing that sea lice dramatically affect the health of sockeye salmon. DFO started to communicate about this evidence that they had of minimal risk, but they don't talk about these studies at all in their communications at the press conference or later on, when they talked to media people.[157]

Recommendation 45

Given the perceived issues with the DFO’s risk assessment of the impact of aquaculture operations in the Discovery Islands on wild fish stocks including:

- the failure to assess the cumulative impacts of the viruses and bacteria detected; and

- the suppression of additional research that could have had a material impact on the overall risk assessment,

that DFO submit to an independent review of the risk assessment, including but not limited to decisions on the assessment’s terms of reference and factors that resulted in the suppression of research findings on the impact of sea lice and possibly other issues with a material impact on the health of wild fish stocks. That there be an independent audit and analysis to determine the accuracy and decision-informing value of the Science Advisory Report presented to the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard on DFO’s risk assessment of aquaculture operations in the Discovery Islands.

Recommendation 46

That the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard provide in writing to the Committee a statement as to whether or not DFO omitted, canceled or in any other way did not complete or make unavailable a 10th CSAS risk assessment examining potential risks to Fraser sockeye.

Dr. Kristi Miller-Saunders described the long delay between the drafting of a report on PRV and its publication. The 2012 report showed that PRV, a virus that may cause heart disease in salmon species, had been detected in farmed Chinook salmon that were suffering from disease. This was the “first sign that PRV might pose a risk to Pacific salmon.”[158] The publication delay “was due to a disagreement between [Dr. Miller-Saunders] and the industry vets on the interpretation of the science. That delay has continued for 10 years, because apparently there needs to be an agreement on the interpretation of the science before the report can be put in, or before a manuscript can be prepared.”[159] Gideon Mordecai wondered whether, if this work had not been “held back from the scientific community, perhaps some of the impact on salmon in B.C. from this virus may have been prevented.”[160]

Recommendation 47