LANG Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Economic Development of Official Language Minority Communities

Introduction

In fall 2023, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Official Languages (the Committee) undertook a study on the economic development of official language minority communities (OLMCs). It aimed to study “the development of best practices and economic models to follow, an analysis of the funding and services provided by economic agencies, an evaluation of current government of Canada programs for entrepreneurs, and the development of new, flexible programs and tools that are sensitive to the realities of official language minority communities and that reflect regional differences as well as the needs of rural communities in order to strengthen the economy and make these regions more attractive.”[1]

This report summarizes the main ideas emerging from the testimony the Committee heard and the briefs it received over the course of its study.[2] The recommendations draw from the evidence to guide the Government of Canada in achieving its socioeconomic development objectives for OLMCs. The report takes into account the new asymmetrical approach of the Official Languages Act, which recognizes that French is in a minority situation in Canada and North America due to the predominant use of English and that the English linguistic minority community in Quebec and the French linguistic minority communities in the other provinces and territories have different needs.

Government of Canada Support

Government of Canada support for OLMC socioeconomic development comes mainly from Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED) and the regional development agencies.

Given the wide range of programs in place, the Committee chose to focus on those initiatives and programs included in the Action Plan for Official Languages 2023–2028: Protection-Promotion-Collaboration (2023–2028 Action Plan): the Economic Development Initiative (EDI) and the Enabling Fund for Official Language Minority Communities. John Buck, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Community Economic Development and Employability Corporation, confirmed that the primary investment in economic development comes through these two programs.[3]

Economic Development Initiative

The Economic Development Initiative (EDI)[4] is a set of programs designed to promote the sustainable growth of OLMCs and the economic benefits of Canada’s linguistic duality. Kasi McMicking, Associate Assistant Deputy Minister, Strategy and Innovation Policy Sector at ISED, explained that “funding is divided between ISED … and the regional development agencies, which administer the financial contributions.”[5]

Role of Federal Partner Institutions

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

First, ISED plays a coordination role.[6] The department “facilitates the discussions about priorities and planning that take place among the agencies, at the national level.”[7] Second, it “conducts economic research and analyzes policies in order to better understand the OLMCs’ economic needs.”[8]

Regional Development Agencies

The regional development agencies manage EDI programming. They are, in a way, federal “one-stop shops”[9] for socioeconomic development in their respective regions. All the agencies are involved in the EDI:

- Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency (ACOA);[10]

- Federal Economic Development Agency for Northern Ontario (FedNor);[11]

- Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario (FedDev);[12]

- Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency (CanNor);[13]

- Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions (CED);[14]

- Prairies Economic Development Canada (PrairiesCan);[15] and

- Pacific Economic Development Canada (PacifiCan).[16]

CED Deputy Minister Sony Perron explained that the regional development agencies are well placed to implement the EDI:

The regional development agencies are a nice vehicle to implement smaller initiatives, because we rely on a common infrastructure to deliver these. If we were an organization created to deliver this $10.2 million over five years, our problems with costs would be terrible because you would need to stand up a structure, but since we are already in that business of supporting and funding community organizations, this is in addition, and that makes us, I would say, pretty lean.[17]

Linda Cousineau, FedDev Vice-President, said that the regional scope of development agencies is an advantage, as it fosters greater local knowledge and connections with communities:

FedDev Ontario leverages its regional footprint to connect with these communities and the knowledge gained informs investments in community capacity building, economic development, entrepreneurship and business growth.[18]

Funding for the Economic Development Initiative

According to Marie-Caroline Badjeck, Acting Director, Strategy and Innovation Policy Sector at ISED, “the funding associated with the Economic Development Initiative was a function of the population” and that this is expected to continue.[19]

As part of the preparatory work for the Roadmap for Canada's Linguistic Duality 2008–2013: Acting for the Future, the distribution of OLMCs population in the regions was the main criterion used to analyze the needs of the various regional development agencies when implementing the EDI. In the Roadmap for Canada's Official Languages 2013–2018: Education, Immigration, Communities, the agencies maintained the financial breakdown. Other considerations were taken into account, such as the high unemployment rate among Francophone populations in certain regions served by the agencies.

Since the Roadmap for Canada’s Official Languages 2013–2018: Education, Immigration, Communities,[20] EDI spending has remained stable at $30.5 million over five years. That said, since 2013, the proportion of funds allocated to the EDI has decreased in the overall government-wide strategy. The EDI actually accounted for 2.7% of total funding allocated to the Roadmap for Canada’s Official Languages 2013–2018: Education, Immigration, Communities,[21] 1.1% of the Action Plan for Official Languages 2018–2023: Investing in our Future[22] and 0.7% of the 2023–2028 Action Plan.[23] Mylène Letellier said that “[t]he fact that this funding is not indexed is a major challenge in the current inflationary context.”[24]

In light of the above, the Committee recommends the following:

Recommendation 1

That Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, given its coordination role under the Economic Development Initiative, and Canadian Heritage, as coordinator of the government-wide strategy on official languages, evaluate the Economic Development Initiative with a view to:

- reviewing how financial resources are allocated to the regional development agencies, particularly by adding a qualitative variable to gauge economic development and the needs of official language minority communities so as not to be limited solely to quntitative data;

- ensuring that the anglophone and francophone minority population calculations are as comprehensive as they are in the Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations: “all persons, in a province in which an office or facilty of a federal institution is located, for whom the first language, or one of the first languages, learned at home in childhood and still understood, is the minority official language and those who speak the minority official language at home, as determined by Statistics Canada based on the published data from the most recent decennial census of population;” and

- indexing the funds allocated to the Economic Development Initiative to ensure they are adjusted to the current economic context.

“By, For and With” Official Language Minority Communities

Under the EDI, regional development agencies work closely with the OLMCs’ main provincial and territorial economic development organizations. These organizations—sometimes called francophone economic development organizations (FEDOs)—administer the EDI on behalf of their regional development agencies. FedNor Vice-President Nick Fabiano said that this is why “most of the funding allocated under the EDI” is in the form of “grants and contributions,”[26] since they are allocated to community economic development agencies. He hastened to add that “if funding is allocated to a business whose aim is to make a profit, then, yes, it comes in the form of a loan, which will subsequently have to be repaid.”[27]

PrairiesCan Assistant Deputy Minister Anoop Kapoor said that in 2020, a three-year pilot project enabled the four FEDOs “to deliver EDI on behalf of PrairiesCan.”[28] Specifically,

Those organizations use the funds allocated for EDI programs to support entrepreneurs, francophone immigrants, and communities, to build the capacities of the communities and create an entrepreneurship ecosystem.[29]

The CDEA, together with its Manitoba and Saskatchewan counterparts, will now manage the Francophone Economic Development Fund for the Prairies, which stems from the EDI.

Patrick Dupuis, owner of the Old School Cheesery in Vermilion, Alberta, said that the partnership between regional development agencies and FEDOs worked well:

We got a lot of support. We applied for support in the context of many programs. The Conseil de développement économique de l’Alberta guided us in finding as much support as we could.

For instance, to help us set up our economuseum, the first in Alberta, the organization helped us get provincial funding through Travel Alberta, municipal funding, and federal funding through Prairies Economic Development Canada, as well as many other grants that were available.[30]

It appears that “by, for and with” is an integral part of the EDI. ACOA Vice-President Daryell Nowlan told the Committee that collaboration with Atlantic Canada’s Acadian and francophone communities is essential to achieving the agency’s mandate. ACOA has a direct presence in francophone and Acadian communities. It is “co-located with other economic development organizations in these communities.”[31]

Mr. Perron said that CED “is convinced that economic development must be done for and by the community.”[32] The agency is “[listening] to the community’s needs … continuously, both through [its] network of business offices and by holding bilateral meetings that bring [together CED]’s senior officials and representatives of [OLMCs].”[33] John Buck told the Committee that the Community Economic Development and Employability Corporation (CEDEC) has a “very strong relationship with [CED]:”[34]

We participate with and partner with [CED] in a couple of ways. One, we have a multi-region agreement because we have a presence in all parts of Quebec. We also have direct involvement of regional offices of [CED], so we have a very direct relationship.[35]

Mr. Fabiano of FedNor was categorical: “Continuing to work with the community is probably the most important thing.”[36]

Enabling Fund for Official Language Minority Communities

As mentioned earlier, the Enabling Fund for Official Language Minority Communities (the Enabling Fund) is one of the 2023–2028 Action Plan initiatives that involve OLMC economic development.

Managed by ESDC, the Enabling Fund helps OLMC organizations “provide employment assistance services, such as employment counselling, résumé writing, interview skills, job search skills and job placement services.”[37] Under this initiative, 14 organizations across Canada signed a contribution agreement that provides them with core and project funding.[38]

Marie-Ève Michon, Director of the Réseau de développement économique et d’employabilité (RDÉE) du Nouveau-Brunswick, pointed out that the Enabling Fund provides her organization with tremendous leverage:

This funding provides tremendous leverage because it enables us to secure other opportunities and funds. For example, over the past five years, the New Brunswick RDEE has worked with 2,800 partners. We’ve used our own funding to leverage $12 million in cash and $4 million in kind, benefiting over 70,000 recipients in New Brunswick with 255 projects.

We’re very excited about the new $208-million fund for employment assistance services. I look forward to seeing what happens next.[39]

The Enabling Fund accounted for about 6.0% of the total funds allocated to the Roadmap for Canada’s Official Languages 2013–2018: Education, Immigration, Communities[40] and about 2.5% of the Action Plan for Official Languages 2018–2023: Investing in Our Future.[41] In the 2023–2028 Action Plan, the Government of Canada increased funding for the Enabling Fund. In the 2023–2028 Action Plan, the Enabling Fund accounts for roughly 7.4% of the total funds.[42]

Regular Programs of Regional Development Agencies

The EDI and the Enabling Fund account for only part of the programs of regional development agencies. OLMCs can access other sources of financial support, drawing on the regular programs of federal agencies and other institutions. Mr. Perron explained that the EDI “is additional funding that has enabled us to expand the services we offer to make sure that services are provided to those communities.”[43] This was echoed by ACOA:

In addition to that, we use our regular programming. For example, in the last 18 months …, ACOA provided $211 million to francophone entrepreneurs or francophone communities. That’s in the last year.[44]

According to Mr. Kapoor from PrairiesCan, “the official languages lens is applied to the evaluation of all departmental funding program applications so that francophone communities also benefit from them.”[45] Since 2018, this has enabled PrairiesCan to fund “186 projects totalling $115 million … identified as extending their activities to benefit francophone communities ….”[46]

Tourism: A Growth Area

Like other agencies, PrairiesCan funds initiatives in tourism, an economic activity Mr. Kapoor described as “an economic driver for francophone businesses in the Prairies.”[47] Mr. Dupuis, an entrepreneur based in Vermilion, Alberta, said he gets a lot of tourists on their way to the Rockies: “They stop in Vermilion to visit our business, because we provide service in French.”[48]

Tourism was also recognized by some witnesses as another area where bridges can be built with the English-speaking majority. In fact, the CDEA has been promoting French and bilingualism with Travel Alberta, the provincial tourism agency, particularly by offering bilingual tours. As part of these tours, participating francophone entrepreneurs have the opportunity to stand out and offer their products and services to tourists. This hard work paid off: “Travel Alberta made the French market one of its priorities for attracting tourists to Alberta.”[49]

The success of tourism initiatives can also be seen in other Western provinces. This is why Roch Fortin, a British Columbia-based entrepreneur, suggested creating “a national tourism register listing all the small businesses that offer services in French in Canada.”[50]

In light of the above, the Committee recommends the following:

Recommendation 2

That Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada create a tourism publication to be updated annually. Such an initiative would better promote tourism in francophone minority communities and enhance the visibility of local businesses while making these services more accessible to francophone tourists, both Canadian and international.

Recommendation 3

That the federal government continue to invest in programs that help tourism grow, knowing that this benefits the economic development of official language minority communities.

Where Communities Fit Within National Programs

FMC organizations find it challenging to access national programs, as calls for proposals are addressed to both majority and minority economic development agencies. Ms. Letellier explained that FEDOs “have trouble competing with majority language organizations responding to calls for funding because they're addressed to all francophone and anglophone stakeholders in Canada.”[51]

Let’s take the example of an organization like ours, which helps 7,000 francophone businesses, and compare it to what an organization that serves anglophones can do. The number of companies is much larger. You’ll understand that we represent 2% of the population, whereas they represent 98%. Sometimes it’s a little difficult to compare us to them. It’s often suggested that we get closer to anglophone organizations. Sometimes it’s possible and it works well, and sometimes it’s a little more complicated.[52]

The Committee occasionally heard it suggested that francophone stakeholders “get closer to anglophone organizations.”[53] As a result, “organizations … often have to rely on the good will of anglophone partners or partners in Quebec to work collaboratively in an equitable manner.”[54] Ms. Letellier believes that “this approach isn’t ‘by and for’ francophones.”[55]

Other witnesses pointed out that a number of programs are not sensitive to the reality of small businesses, who sometimes find it difficult to navigate the range of programs available.[56] They also complained about the amount of paperwork involved: “small businesses often walk away because they don’t have the resources to fill out all the paperwork. A big business can check with its accountant, push a button and produce all the required information.”[57] As well, Cathy Pelletier, General Manager of the Edmundston Region Chamber of Commerce, spoke about what she considers to be excessive red tape:

There is no denying that we’ve run into issues with bureaucracy in the past. We still do, and we always will.

It hinders our economic development in many ways. Certainly, things could be improved. We have to jump through a lot of hoops just to achieve something minor and tangible. It’s such a complicated process. We have to knock on a lot of doors, just to be able to do something locally or regionally. Sometimes, it’s even more complicated when working with our counterparts in other chambers of commerce.

Unfortunately, a lot of businesses walk away from their plans because of it.[58]

In light of the above, the Committee recommends the following:

Recommendation 4

That the Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Official Languages reiterate to his Cabinet colleagues the importance of official language minority communities when making grant decisions.

Recommendation 5

That Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada and regional development agencies review the funding application process stemming from the Economic Development Initiative and the Enabling Fund for Official Language Minority Communities in order to reduce administrative burden and improve accessibility for economic organizations and entrepreneurs.

Socioeconomic Development of Official Language Minority Communities: Current Situation

Situation of Quebec’s English-Speaking Communities

Discussion on Variables

Enumeration of Quebec’s anglophones

As explained by François Vaillancourt, there is some controversy over the choice of variables used to compare the socioeconomic development of linguistic groups.[59]

There are many ways to count a group. Representatives of the Provincial Employment Roundtable (PERT), a research and support organization for Quebec’s English-speaking communities, encourage using first official language spoken (FOLS). According to Statistics Canada, the “first official language spoken refers to the first official language between English and French spoken by Canadians. It is determined from the knowledge of languages, mother tongue and language spoken most often at home.”[60] PERT prefers this variable because it seems more inclusive. It accounts for approximately one-third of immigrants to Quebec. It actualizes the self-determination of English-speaking Quebeckers[61] and “better demonstrates what’s needed on the ground.”[62] Using the FOLS variable, there are more than 1.2 million anglophones in Quebec, comprising 14.9% of the province’s population.[63]

From the Government of Canada’s point of view, Quebec’s English-speaking community is a linguistic minority since Quebec is majority francophone. Based on FOLS, it represents 55.8% of Canada’s total OLMC population. It is therefore demographically the largest OLMC within a Canadian province.[64] In its brief, PERT states that this community has been in decline.[65] PERT representatives explained as follows:

This community has also experienced considerable demographic and economic shifts in the last four decades. In 1977, the Québec government adopted the Charter of the French Language, commonly known as Bill 101, which established French as the common language of work and society in Québec. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, an exodus of English-speaking Quebecers led to declines in the populations of English speakers in most regions of Québec.[66]

However, the number of people in Quebec who speak English as their FOLS has increased: “their proportion of the population rose from 12.0% in 2016 to 13.0% in 2021.”[67]

Pierre Serré believes that FOLS is a variable that is derived to meet the requirements of the Official Languages Act and that it does not provide a realistic picture of the socioeconomic situation of Quebec’s English-speaking minority. He argued that the main language used at home “is the most reliable indicator of the number of speakers of a language.”[68] Using this variable, the language of use for 986,000 people is English.[69] Prof. Vaillancourt agrees: “[T]he first official language spoken … is not as good an indicator of group membership as are the mother tongue and the language spoken at home.”[70] These two variables “would be the two best indicators.”[71]

Income Variables

As for data on the incomes of Quebec’s anglophones, some, including PERT, use the variable “median employment income.” Mr. Salter explained that “median employment income is what most economists use, as a comparative average has distorting effects.”[72] Mr. Salter went on to say that “there’s a wide social and economic gap within the anglophone community, so that bumps the average up.”[73] Mr. Salter believes it is important to use a variable other than the average, since “if we look only at the average, we can’t target the people who need help.”[74] Mr. Salter said that despite “higher levels of educational attainment,” “a higher proportion of Québec’s English-speaking visible minorities (19.2%) fall below the low-income measure compared to the total English-speaking community (14.7%).”[75] Regarding anglophone immigrants, “15.2% … live below the low-income cut-off, slightly exceeding the overall rate of 14.7% for the English-speaking community.”[76]

Prof. Vaillancourt believes that “the median tends to overlook the fact that, by definition, there are people to the right or left of the median, dragging the average up or down.”[77]

Using “first official language spoken” as a language variable and “median employment income” as an income indicator, Mr. Salter found that Quebec’s English speakers “experience higher levels of unemployment, lower incomes and higher rates of poverty than the French-speaking majority in Quebec, as well as all other OLMCs across the country.”[78] As for unemployment, PERT representatives also said that Quebec’s English community experiences “disproportionately higher rates of poverty compared to French speakers.”[79] According to 2021 Census data, English speakers had an unemployment rate of 10.9%, which is four percentage points higher than that of Quebec’s French speakers (6.9%).[80] As for median employment income, PERT representatives told the Committee that Quebec’s English speakers have incomes “$5,200 lower than French speakers.”[81]

Prof. Serré criticized the cross-referencing of the FOLS and median employment income variables. Using these two variables, the “median employment income [for English-speaking Quebecers] was $36,000 and the average employment income was $52,850.”[82]

According to Prof. Serré, this is due to the fact that FOLS captures 267,000 “non-anglophones,”[83] reducing the community’s median employment income by $4,000 (11.1%) and its average employment income by $4,130 (7.85%).[84] However, these individuals “come largely from allophone immigrant backgrounds with little knowledge of English and even less of French.”[85] Prof. Serré stated that “with incomes well below average, it is no surprise that this group is dragging down the FOLS’s median income for English speakers.”[86] Mr. Salter acknowledged that “unemployment and income data shows that there are disparities even within the English-speaking community, with English speakers living in the regions, as well as visible minorities, immigrants, first nations and Inuit, experiencing worse outcomes.”[87]

Prof. Serré believes that it would be preferable to use the variables average employment income or average after-tax income. He stated that even if FOLS is used, “the average employment income of anglophones is slightly higher than that of francophones ($48,720 vs. $46,240 average employment income).”[88] Furthermore, “calculating average employment income based on language of use widens the income gap in favour of anglophones even more ($52,850 for anglophones vs. $46,560 for francophones).”[89]

Prof. Serré believes it is just as important to factor in the “language of work” variable. He stated that the 2021 Census shows that earnings associated with working in English are “moderately higher than the median, and dramatically higher for the average, when compared to earnings associated with working in French.”[90]

When English is the language of work, median employment income is $4,600 higher ($43,000 vs. $38,400), and average employment income exceeds that of individuals working in French by $15,000 ($61,800 vs. $46,640).[91]

Citing this data, he said that “working in English in Quebec in 2021 meant earning an average income more than 30% higher than that of people working in French.”[92] According to Prof. Serré, “this leads to high levels of English language substitution among francophones and allophones, a major contributing factor of anglicization.”[93]

Prof. Serré concludes that the use of FOLS is a federal strategy to distort the socioeconomic profile of Quebec’s English-speaking minority:

As a result, the federal government has artificially impoverished Anglo-Quebeckers to reverse the dominant reality, which places anglophones at the top of the cultural division of labour, even in 2021.[94]

Employability Needs of English-Speaking Quebeckers

Mr. Salter said that three main factors make it difficult for English-speaking Quebeckers to enter the province’s labour market:

[F]irst, a lack of access to specialized and targeted English-language employment services; second, an ineffective French-language learning system, particularly for adults in the labour market, and the lack of diverse programs offered to support the language-learning needs of individuals in key professions; and lastly, a lack of access to English-language skills training programs due to the limited availability of these programs across the province, particularly in the regions.[95]

PERT representatives raised access to French-language training. On this matter, Mr. Salter stated that when anglophones talk about the challenges they face in the labour market, “the top thing identified for us is French-language barriers.”[96] That is why PERT has “spent a lot of [its] organizational effort trying to build a well-functioning French-language training system.”[97] To illustrate what his colleague said, Mr. Walcott shared an anecdote demonstrating the importance of diversifying language training programs and adapting them to learners’ needs:

As part of our research, we interviewed an American who was already working a bit in Quebec and who moved elsewhere in Canada. According to him, the francization pathway for newcomers to Quebec was not adapted to his abilities. His French was already at an intermediate level and he wanted to move to an advanced level.

However, the courses currently being offered to new immigrants in Quebec are not at that level. They are actually cultural courses and core French courses, where you learn how to order a coffee, for example.[98]

Mr. Salter gave a series of recommendations to improve the employability of English-speaking Quebeckers. First, he recommended creating an employment strategy for Quebec’s anglophones “recognizing employment as a cornerstone of economic development and community vitality in the English-speaking community of Quebec.”[99] Second, he said that there needs to be an improvement in the relationship between federal institutions and the English-speaking community in Quebec regarding economic development.[100] In this respect, he said that interdepartmental coordination must be improved, particularly between Canadian Heritage, as coordinator of the government-wide official languages strategy, and Employment and Social Development Canada.[101] Since employment is a jurisdiction shared by the Government of Canada and the provincial and territorial governments, a fourth step would be to improve coordination between the governments of Canada and Quebec. Fifth, Mr. Salter stressed the importance of investing in research on the employment and economic development of the English-speaking community. Lastly, Mr. Salter recommended developing “a pan-Canadian plan to strengthen investments in free and accessible adult French-language training programs.”[102]

It is important to stress that rural communities must be included in government measures. Mr. Salter explained that “the situation in terms of the unemployment gap and the income gap can widen significantly, Gaspésie being one example of where there are significant gaps.”[103] That said, Mr. Salter added that “there are still needs in an urban setting, particularly for visible minority communities and other sub-communities within the English-speaking community.”[104]

Quebec English-Speaking Communities’ 10-Year Economic Plan: Prioritizing Collaborative Economic Development in Quebec

The Community Economic Development and Employability Corporation (CEDEC) is the organization designated and funded by the Government of Canada to coordinate the economic development of Quebec’s English-speaking communities. During his appearance, Mr. Buck pointed out that Quebec’s English-speaking community has a 10‑year economic development plan. This 10-year plan “lays out bold and targeted results to further strengthen the contribution of English speakers to growing and developing Quebec’s economy while leveraging these efforts to reduce the disparities limiting its contribution.”[105]

Collaborative economic development was identified as a best practice and business model for Quebec’s English-speaking communities. Mr. Buck cited a project in the Quebec City region that brings together the Valcartier Family Resource Centre, Ver Mac and school service centres. They work together to recruit English-speaking or bilingual staff to fill vacant positions in the company, which benefits the local economy. Mr. Buck said that this illustrates the tangible results that can be achieved by a partnership between the public and private sectors and civil society.

CEDEC believes it is imperative that the Government of Canada include the positive measures taken for the socioeconomic development of Quebec’s English-speaking communities within a collaborative development model. Such a model has the potential to create closer ties between the communities and the province’s francophone majority in terms of business plans and socioeconomic development.[106] CEDEC said that the 10‑year economic development plan is “the road map the federal government should be guided by to ensure the community’s full participation in growing and sustaining Quebec’s economy while simultaneously reducing the economic disparities limiting such participation.”[107] CEDEC therefore recommends that the Government of Canada “maximize its investment … by aligning and coordinating its funding to actively support the achievement of the economic outcomes outlined in the ESCQ’s 10-year economic development plan.”[108]

In light of the above, the Committee recommends the following:

Recommendation 6

That the Government of Canada recognize that collaborative economic development is one of the socioeconomic models best suited to the needs of Quebec’s English-speaking communities. That it take collaborative economic development into account when implementing positive measures targeting the socioeconomic development of these communities.

Recommendation 7

That the Government of Canada adopt an employment strategy for English-speaking Quebeckers that, while noting that this is an area of shared jurisdiction:

- prioritizes access to free and accessible French-language training programs;

- works toward forging a partnership between the participating federal institutions and Quebec’s English-speaking communities;

- works toward improving Canada–Quebec intergovernmental and interdepartmental coordination on the employability and economic development of Quebec’s English-speaking communities; and

- funds research into the employability and economic development of Quebec’s English-speaking communities.

Recommendation 8

That the Government of Canada request that Statistics Canada collect language data in its monthly Labour Force Survey in order to provide socioeconomic development stakeholders with an up-to-date picture of the national, provincial, territorial and regional employment and unemployment rates for official language minority communities.

Socioeconomic Situation of Minority Francophones

Rural Communities

As several witnesses mentioned, most francophone minority communities (FMCs) are rural. In the second edition of the White Paper on the Economic Development of Francophone Minority Communities, RDÉE Canada states that “nearly 430,000 businesses across [Canada] are created and managed by Francophones, which represents $130 billion in economic benefits outside Quebec and 19.5% of our GDP [gross domestic product].”[109] However, most (50%) of these businesses are in Ontario.[110] As RDÉE Canada explained, “in the other provinces and territories, Francophone populations are often isolated or marginalized, and it becomes more difficult to develop a regional or geographic Francophone entrepreneurial spirit because of the low volume of Francophiles.”[111]

For Pierre-Marcel Desjardins, a professor at the University of Moncton, the rural nature of francophone communities is a key feature that must be reflected in government support measures:

When we talk about public policy, it’s extremely important to have policies that encourage rural development, because that’s where francophones are concentrated. Often, when people move to more urban environments, mainly for economic and financial reasons, the rate of assimilation increases.[112]

Municipal Power to Foster the Socioeconomic Development of Manitoba’s Francophone Communities

In Manitoba, the economic development of francophone communities is led by bilingual municipal leadership. Madeleine Arbez, Executive Director of the Economic Development Council for Manitoba Bilingual Municipalities (CDEM), explained that “this unique model not only provides significant leverage, but also creates conditions conducive to the infrastructure and foundation needed to deliver programs, activities and events that make living in French normal and that support the development and sustainability of the francophone community.”[113]

Thanks to the leadership of the Association of Manitoba Bilingual Municipalities, the CDEM and the AMBM Group – “not to mention the borrowing capacity of the rural municipality of Taché[114]” – a project to build a community centre is under way in Taché. Ms. Arbez said that “the municipality sees the project as a perfect opportunity to bring together the francophone community and help it grow.”[115] This is an example of how the collaborative work of FEDOs and bilingual municipalities, among other stakeholders, can result in successful projects for the francophone community.

As mentioned earlier, the work done by the FEDOs to raise awareness and promote the socioeconomic benefits of French and bilingualism to the majority can have a positive impact on the status of French. For example, some predominantly English-speaking municipalities are bringing in the CDEM to discuss the possibility of becoming a bilingual municipality:[116]

In one of the municipalities that invited us, the people were all anglophones. They told us they wanted to become a bilingual municipality. They recognized that they had francophone colleagues and neighbours, as well as francophone businesses serving clients and offering opportunities.[117]

On another note, Manitoba’s francophone community model has potential when it comes to making regulations to support implementation of the Use of French in Federally Regulated Private Businesses Act. As explained by Ms. Arbez, “bilingual municipalities are the home of many minority language communities.”[118] This means that bilingual municipalities represent one of several bases on which regions with a strong francophone presence can be defined.

In light of the above, the Committee recommends the following:

Recommendation 9

That the Government of Canada consider the bilingual municipalities in the Canadian Prairies when developing regulations for designating regions with a strong francophone presence.

Conclusions of the National Summit on Francophone Minority Economies

During his appearance before the Committee, Yan Plante, President and CEO of the Réseau de développement économique et d’employabilité (RDÉE Canada), stated that the 2022 National Summit on Francophone Minority Economies helped establish a certain number of findings with regard to the Government of Canada’s support. First, “the point that was most often noted in the discussions was the desire to see the creation of a government plan dedicated to the francophone economy in minority communities.”[119] RDÉE Canada believes that this plan should serve to strengthen interdepartmental and intergovernmental efforts, as well as collaboration with FMCs, to achieve their socioeconomic development objectives.

Second, some Summit participants pointed out that “there are programs, but they are scattered among all sorts of government departments that do not have the same level of accountability.”[120] Mr. Plante said that “people would like there to be a kind of single window, and for francophone economic development, they would like to be directed to a single place.”[121]

Lastly, some of the 2022 Summit participants said that “the Action Plan for the Official Languages … and the other initiatives are all excellent measures, but they do not necessarily promote economic development by and for francophones.”[122]

Definition of Minority Business

There is no official definition of an OLMC business or contractor. As Mr. Pierre-Marcel Desjardins explained, it is difficult to come up with one: “Is it the entrepreneur who speaks French, but whose employees speak English? Is it foreign ownership? Nailing down this definition is often the biggest challenge.”[123]

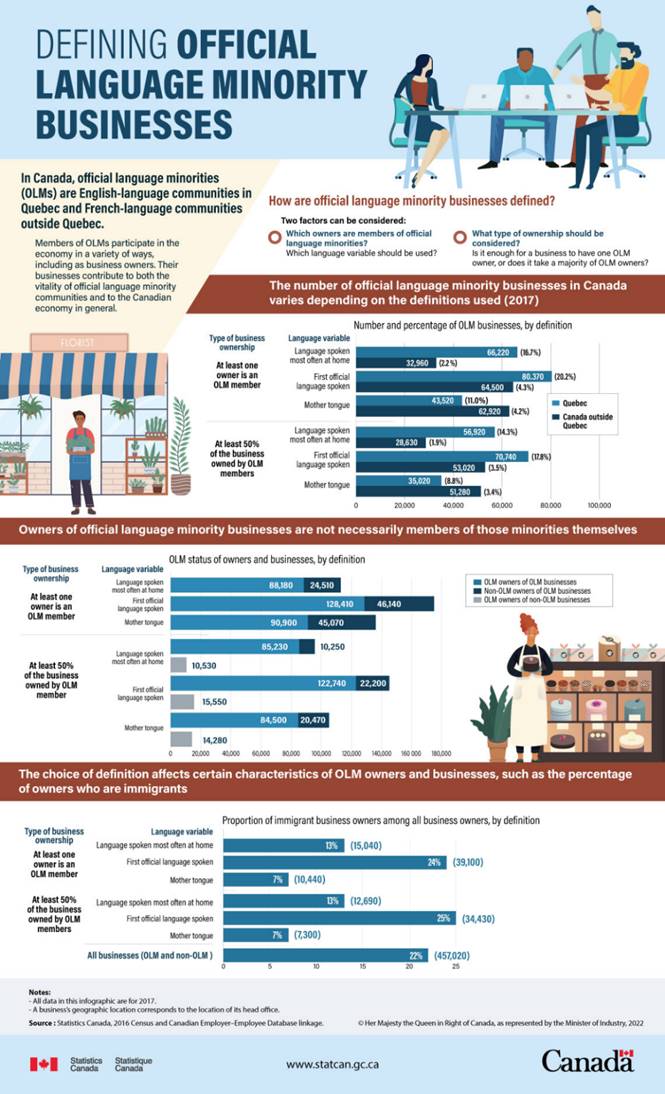

In 2022, at ISED’s request,[124] Statistics Canada conducted the study Official Language Minority Business Definitions: Potential and Limitations. It was intended “to test and document the data outcomes of different official language minority (OLM) business definitions.”[125] Ms. McMicking said that Statistics Canada was not looking to come up with a definition, but rather “to develop a methodology for identifying businesses that might be associated with official language minorities.”[126] According to the report, three types of ownership (all owners are considered, only the owner is considered, owners holding a certain percentage of the business are considered[127]) and three language variables (language spoken at home, first official language spoken and mother tongue) were combined to create nine possible ways of defining OLM businesses. Inevitably, the choice of variables depends on the analytical objectives pursued:

[I]f the objective is to study the characteristics of OLM businesses, a more conservative approach such as the one based on the majority ownership criterion would be more appropriate than a more inclusive approach, as the former will end up including several non-OLM owners that tend to have different characteristics than their OLM counterparts. At the very least, the choice of the more inclusive definition may require further analysis to assess the effect of including more non-OLM owners on results. Additionally, even if there is a non-negligible number of businesses that are 50% owned by OLM, analyzing those businesses separately has proven difficult due to their small numbers.[128]

Statistics Canada produced infographics based on the above study.[129] The infographic included below is entitled Defining official language minority businesses.

Figure 1—Defining Official Language Minority Businesses

Source: Statistics Canada, Defining official language minority businesses, 21 July 2022.

For some, the lack of a definition can have far-reaching consequences. Mr. Desjardins believes that this complicates access to evidence-based data on francophone entrepreneurs.[130] For others, the lack of a definition can mean that certain businesses or entrepreneurs receive federal funding without actually contributing to the vitality of francophone communities. On this point, however, the economic development agencies are quite confident that they have put mechanisms in place to ensure that the funding allocated to OLMCs is put to good use. As seen earlier, some regional development agencies have handed over implementation of the EDI to provincial or territorial FEDOs. As well, the agencies say that they are close to the communities they serve. Mr. Traynor said that CanNor is working “very hard on the ground to understand the francophone community and support the businesses directly. We work with the francophone associations to clearly identify who is francophone with the communities in the north. They’re quite tight, and they usually know who’s who.”[131]

FedNor uses a definition based on the Statistics Canada study for ISED:

Businesses are required to state on their applications whether they are francophone, meaning that at least 50% of their business is owned by francophones.[132]

As well, FedNor has FMC socioeconomic development experts. These experts, especially those assigned to programs such as the EDI, are involved in “auditing businesses and associations.”[133]

In any event, Mr. Desjardins believes that any definition of a French-language minority company must be broad:

In francophone minority communities, it doesn’t matter if the president, owner or manager of a business is anglophone, as long as the employees can operate and work in French. I would consider that a francophone business, in a way, because the francophones in those communities can work there.

I tend to have a slightly broader definition of what constitutes a francophone business. Let’s consider, for example, a multinational corporation that sets up in a community, but employs francophone people from that community. Even if it’s a German company, it still enables people to live and work in their community, and in French. Given these kinds of situations, I think we need to have a fairly broad definition.[134]

In light of the above, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 10

That Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada adopt a representative definition of Francophone businesses in minority situations. That this definition take into account, among other criteria, that a business where employees can function and work in French is a francophone business.

Key Measures to Foster the Socioeconomic Development of Official Language Minority Communities

In the following quote, Kenneth Deveau, Chief Executive Officer of the Conseil de développement économique de la Nouvelle-Écosse, clearly explains what OLMC vitality is based on:

Basically, we’re talking about the vitality of our official language minority communities, or OLMCs. A community’s vitality is defined by its ability to maintain itself as a distinct entity and to flourish within that context, and it can be summed up in three points: the status of the group, its language and culture, its institutional completeness and, of course, demographic factors. The latter receives much of our attention, but they are often the consequence of the other two factors.[135]

Increasing the population of OLMCs—both francophone and anglophone—is fundamental to their socioeconomic development. Obviously, people are needed to work within the community and institutional networks that foster participation in society in the minority language. This makes it imperative to address the issue of employability. A community that is able to offer a diverse range of services in the minority language is also appealing, making it easier to encourage its young people to stay and to attract immigrants to settle there.

Tackling the Labour Shortage

There is obviously a labour shortage across the country. FMCs are particularly affected by this shortage, which has weakened their community and institutional networks, and consequently has negatively impacted their ability to offer a full range of services in the minority language. However, there are various ways to address the labour shortage in OLMCs. For example, the Edmundston Region Chamber of Commerce strives to involve the entire community in improving the delivery of French-language services and the success of local businesses. The “Retiree Employment Agency” project has a pool of retirees interested in working at their own pace. “Emploihabilité Plus” assists individuals with special needs as they enter or re-enter the labour market.

Enhancing the Skills of Minority Francophone Adults

As the Réseau pour le développement de l’alphabétisme et des compétences (RESDAC) explained, “the knowledge economy has been transforming the work ecosystem.”[136] As a result, employers across the country are already requiring new skills.[137] According to RESDAC President Mona Audet, it is critically important for minority francophone adults to have opportunities to acquire new skills so they can succeed in the labour market:

Clearly, economic development is one of the developmental cornerstones for francophone and Acadian communities. It would be hard to imagine our growth and our contribution to Canada’s prosperity without skilled human resources, jobs, businesses and structures to support economic development.[138]

Canada has come up with nine “Skills for Success.”[139] However, FMCs have their own unique needs and issues. That is why RESDAC, together with the Table nationale sur l’éducation, tailored the “Skills for Success” program to the needs of FMC learners. They came up with four FMC-specific skills: “language skills, … identity affirmation, citizen engagement and coexistence.”[140] Mr. Desgagné, RESDAC’s Executive Director, said that this is the first time that Canada’s skills framework has been adapted for a minority. RESDAC’s work in this area even enjoys the support of UNESCO.[141]

RESDAC also explained that the educational materials used to teach the identified skills must be designed based on the specific needs of FMC learners and unique features of the various communities. This is a basic principle of adult education, or andragogy:

In andragogy, we train adults, and it’s the context that determines the needs. The work context in Montreal is very different from that in Fort McMurray or Caraquet. That’s the approach we take when we try to find solutions in terms of jobs or when we develop a training program to meet local needs.[142]

Ms. Audet illustrated Mr. Desgagné’s remarks as follows:

In Manitoba, all our literacy programs are based on Louis Riel, on the Festival du voyageur, on the francophone community, on rural communities, and so on. … It means going to find what exists in our communities to teach it to our learners.

I also know that my colleagues all over the country do the same thing, because people need encouragement to learn more about their host community or the community in which they have been involved for a long time. Francophones also need to design and review the documents.[143]

RESDAC and its partners also recognize the importance of promoting skills acquisition by individuals. That is why RESDAC and the Institut de coopération pour l’éducation des adultes have launched “Francobadges.ca,” a new pan-Canadian francophone platform that uses open digital badge technology to recognize learning in francophone communities across Canada. RESDAC explained that “these are certifications that are awarded for skills acquired in informal training, whether structured or in a self-learning context.”[144] The advantage of this type of system is that it in place internationally. As well, Canada has announced “a $75 million investment in a similar platform … in the health care field.”[145]

RESDAC is also “putting in place the whole process of skills recognition”:

We have a matrix comprising several skills frameworks at international, national and provincial levels. This allows us to recognize skills. What’s more, the wonderful thing is that our partners in post-secondary education, at college and university levels, can certify this.[146]

The tools presented by RESDAC have the potential to address some of the issues raised by Reginald Nadeau, President of the Haut Madawaska Chamber of Commerce: “[C]redential recognition programs can be very onerous because there is too much bureaucracy. They are also extremely expensive for our workers.”[147]

RESDAC has quite a bit of momentum: it has involved major partners such as the Table nationale sur l’éducation and the Canadian Commission for UNESCO. It hosted the national summit on learning for Canada’s Francophonie in March 2024. It was at this summit that it launched the RESDAC dashboard—Topo—which provides evidence-based data on community needs and assets. RESDAC is also planning to open a skills development centre of expertise and create a competency framework.[148]

Regarding Government of Canada support, RESDAC argued for more robust accountability from federal institutions. Ms. Audet wants to ensure that funding earmarked for francophones is “given to francophones and to the appropriate people.”[149]

In light of the above, the Committee recommends the following:

Recommendation 11

That under section 41(7)(a.1) of the Official Languages Act, Employment and Social Development Canada include provisions in the funding agreements with the provinces and territories that set out their obligations regarding the rights of official language minority communities. That the department require enhanced accountability from stakeholders, particularly with respect to funding for adult literacy and skills acquisition geared to official language minority communities.

Meeting the Socioeconomic Challenges Facing Francophone Minority Women

The Alliance des femmes de la francophonie canadienne (AFFC) said that “the action plan for official languages formally recognized women’s crucial contribution to the development of [OLMCS].”[150] The AFFC believes that this recognition must be reflected in investments, particularly in FMC socioeconomic development: “Ongoing concrete investments in francophone and Acadian women are essential to recognize their contribution and support the economic development of our communities.”[151]

Most federal regional development agencies support organizations working to improve the socioeconomic conditions of women, whether by enhancing their employability or supporting their efforts to start up a business. Ms. Cousineau said that there are “a lot of opportunities to support women through the economic development initiative [EDI] and regional funding programs.”[152] For example, FedNor[153] and FedDev[154] support the PARO Centre for Women’s Enterprise, an Ontario-wide organization specializing in supporting women’s economic success.[155]

Repreneurship – acquiring a business and maintaining its mission and entrepreneurial culture – is also an interesting option for supporting women’s socioeconomic development. FedDev contributed to the success of such a project in Eastern Ontario. L’Orignal Packing, a well-established food distribution company, was taken over by the owner’s daughter.[156] RDÉE Nouveau-Brunswick manages the “Solution Succession” program. Marie-Eve Michon, Director of RDÉE Nouveau-Brunswick, said that her organization does “a lot to support start-ups, but [it] also wanted to provide support for takeovers.”[157] She said that “women who want to buy a business don’t face the same challenges as men.”[158] The four Atlantic provinces and Saskatchewan are involved in this program. The program “has been running in New Brunswick for three years and has helped 200 women, 97 of whom have received personalized coaching to help them through the process of buying a company from start to finish.”[159]

Immigrant Women and Socioeconomic Development

Much of the AFFC’s testimony focused on the unique needs of immigrant women that Nour Enayeh said “immigration programs and services fail to take into account.”[160] However, these needs are extensive. As explained by AFFC Executive Director Soukaina Boutiyeb, “oftentimes, immigrant women are under pressure to not only immigrate successfully as fully contributing women, but also look after their families.”[161] These multiple responsibilities affect their ability to participate in the social and economic life of their host community.[162]

The AFFC therefore requests that “the government uphold its commitment to gender equality and take the needs of francophone immigrant women into account in its immigration programs and services.”[163] Ms. Boutiyeb added that programs must be flexible and customized: “the idea is to provide immigrant women with services tailored to their needs and to take into account the fact that migration pathways are changing. The needs of women today can change tomorrow.”[164]

Certain federal institutions have specialized programs that promote employability, skills development and entrepreneurship among francophone immigrant women. Linda Cousineau gave the example of the Mouvement ontarien des femmes immigrantes francophones, which received a non-repayable contribution from the Black Entrepreneurship Program’s ecosystem fund. One of the recipients is the founder, owner and operator of Dûnu Donuts in Ottawa, which is a street food and donuts business that is bringing African cultural food to new audiences.[165]

The Care Economy

Caregivers are part of what Statistics Canada calls the “care economy,” which is “the sector of the economy comprising the provision of paid and unpaid care work that supports the physical, psychological, and emotional needs of care-dependent groups.”[166] According to Statistics Canada, women more often take on the role of caregivers, providing the bulk of unpaid care.[167]

In its brief, the AFFC stressed the importance of improving access for francophone caregivers to support programs in the language of their choice:

Caregivers are in a unique situation, where their mental and physical health is paramount, and access to relief services is in high demand. During the pandemic, caregivers’ needs changed, but one thing remained unchanged: their need to access resources and services in French. COVID-19 dramatically increased caregiver isolation by making it harder to access relief services, for example. Granting tax credits isn’t enough as caregiving is a full-time job. Resources and services, including relief services, transportation and access to mental and physical health care in French, must be available at all times.[168]

Many caregivers are forced to quit their jobs to take care of a loved one.[169] Frankly, these women caregivers “need access to French-language health care and services tailored to their realities.”[170] Lastly, access to French-language respite and support services for caregivers is more of a problem in rural areas.[171]

In light of the above, the Committee recommends the following:

Recommendation 12

That the government invest in making it easier for francophone and Acadian minority caregivers to access resources and services.

Combatting Gender-Based Violence

The AFFC raised the issue of gender-based violence: “Since the pandemic, Canada has seen a worrying upsurge in gender-based violence.”[172] Although the AFFC recognizes the contribution of the National Action Plan to End Gender-Based Violence, it is disappointed that the plan overlooks francophone women:

Despite its focus on intersectionality, this sweeping plan failed to include francophone and Acadian women and doesn’t commit to dedicated funding for them, further marginalizing and excluding them.[173]

The AFFC therefore made the following recommendation:

[W]e recommend that the government top up its investment to implement the National Action Plan to End Gender-Based Violence and earmark funding specifically for organizations representing francophone and Acadian women in minority communities.[174]

In light of the above, the Committee recommends the following:

Recommendation 13

That the Government of Canada top up its investment to implement the National Action Plan to End Gender-Based Violence and earmark funding specifically for organizations representing francophone and Acadian women in minority communities.

Encouraging Young People to Stay in Official Language Minority Communities

“Brain drain” is not a new phenomenon and affects most rural communities. It is a major issue for OLMCs since it jeopardizes their vitality and, in the long term, their survival. As Kenneth Deveau explained, the exodus of young people is a “double loss”:

Mobility means we’re losing our young people, and that’s a double loss. They’re leaving our regions … to pursue post-secondary education. We’re losing not only our young people, but also the future leaders of our communities. The best and the brightest leave us and often don’t come back.[175]

Focusing on Entrepreneurship

Regional development agencies have developed entrepreneurship programs designed to encourage young people to start a business in their region so they can settle there and create jobs. In some cases, French-language educational institutions collaborate on these projects. FedNor and ACOA have mentioned their involvement in such school-based entrepreneurship initiatives.[176],[177] Étienne Alary, CDEA Executive Director, explained that in Alberta, this strategy is focused on rural economies:

We’ve had an impact on rural economic diversification. For rural areas, the youth exodus is a huge challenge. To address that, we’ve created various financial literacy and entrepreneurship workshops, as well as camps for young francophone entrepreneurs. Our initiatives have reached 2,500 elementary and high school students over the past year and led to the creation of a number of school-based businesses.[178]

Partnerships between communities, regional development agencies and minority educational institutions also help align the supply of training programs with the needs of the local job market. According to Mr. Nowlan, this is a way of meeting the labour needs of local businesses, which in turn provide opportunities for graduates in their regions.[179]

Regarding OLMC entrepreneurial development, the Committee recommends the following:

Recommendation 14

That the Government of Canada inform stakeholders about, call their attention to and reiterate, the existence of a specific lens for official language minority communities designed to promote and encourage the creation of new businesses serving these communities.

Increasing Community Appeal

The appeal of OLMCs depends largely on the variety and scale of services they offer. Ms. Arbez said that the active offer of services is one of the vitality indicators for OLMCs.[180]

However, it appears that French-language services in many communities are clearly insufficient. Speaking of settlement opportunities in FMCs, Mr. Desjardins said that “what I do see as a serious problem is when people want to stay in their communities—often rural francophone communities—but they’re forced to go elsewhere because of the lack of opportunities and choices.”[181] Ms. Michon agrees: “It’s difficult to choose a rural area because the cost of living is extremely high. There’s no public transit. So it’s much harder to choose to settle in a small community in the northern part of the province.”[182]

Mr. Desjardins believes that the government should focus on creating and improving minority language services in rural communities: “All the French-language services we’re able to bring to rural areas contribute to the growth of francophone minority communities, some of which are often concentrated in more rural areas.”[183]

Quebec’s English-speaking rural communities have also seen a decline in services in English. Mr. Salter said that organizations in the regions “could be better supported to work on employment with a ‘for us, by us’ model, and we think the federal government could play an important role in that.”[184] As is the case in FMCs, in Quebec, “each region is different as well, so it can get complicated fast, but that’s why you need a tailored approach for each region.”[185]

Focusing on Flexible Work Arrangements

Mr. Deveau believes that focusing on flexible work arrangements is a key strategy to encourage young people to stay in or return to the regions. Such an approach could help address two issues: housing problems in urban areas and declining OLMC populations in rural areas:

First, some young people from our regions are extremely qualified and live in major Canadian cities, which are experiencing serious housing problems. We have connectivity issues in our regions. Addressing those issues and developing strategies that would support people working remotely would help bring back young people who have potential and who are able to exercise leadership in our regions, from our regions.[186]

Mr. Deveau suggested that regional economic development agencies such as the Conseil de développement économique de la Nouvelle-Écosse could create these strategies.[187]

Gaëtan Thomas, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Conseil économique du Nouveau-Brunswick, said that the Government of Canada could encourage remote work, when possible, to foster OLMC vitality: “A lot of people in Ottawa and Fredericton work from home. Why not give these people the option of working from home in Dalhousie, Campbellton or Tracadie?”[188]

Mr. Desjardins proposed two solutions to improve connectivity and mobility in OLMCs so that community members can take greater advantage of flexible work arrangements: high-speed Internet, and improved transportation, which in this case means better access to commercial flights.

[W]hen it comes to mobility, we want to stay in rural areas, but we need access to what is happening elsewhere. For that, we need high-speed Internet access, which is unfortunately not always available in rural areas.

On the other hand, without necessarily having an airport in every community, we would have to have air services that would enable us to go to the major centres once or twice a month to attend meetings and participate in development. These two elements would enable people to live in rural areas, in our francophone communities, and to remain open to the rest of the country and the rest of the world.

High-speed Internet and air transportation are two fundamental elements.[189]

In light of the above, the Committee recommends the following:

Recommendation 15

That official language minority communities be identified in the High-speed Internet for all Canadians initiative as priority communities.

Seeing Child Care as a Driver of Socioeconomic Development

The Official Languages Act recognizes certain areas of activity as essential to the vitality of communities. Early childhood is a key sector for ensuring the sustainability of francophone minority communities. Attendance at French-language day care helps pass on the French language, as well as develop a francophone identity and an attachment to the community.

Fostering Employability and Entrepreneurship Through Child Care Services

Early childhood services can also be seen through the lens of FMC socioeconomic development. Day care centres create jobs and offer business opportunities. They also allow parents to work outside the home and are one of the services that make an OLMC more appealing to families, encouraging them to settle there.

Day care allows parents to participate in the labour market as either a business owner or an employee. Karen Greve Young, Chief Executive Officer of Futurpreneur Canada (a national organization dedicated to the promotion and success of entrepreneurship), explained that “access to child care is a priority for both women and men entrepreneurs under 40 whom we support.”[190] For them, “child care that frees up their time to do their business is a need.”[191]

Similar reasoning applies to parents currently in or looking to enter the labour market. Mr. Desjardins explained that “we must help parents who want to enter the workforce. I think early childhood services are essential to promote the integration and retention of these people in the workforce.”[192] Ms. Pelletier said that in New Brunswick, “a lot of day care services are saturated.”[193] As a result, “Some people can’t go to work … Resources are very limited in these areas.”[194]

The AFFC also raised the importance of day care when it comes to the employability of francophone women, especially immigrants. Soukaina Boutiyeb believes it is crucial that the needs of immigrant women be taken into account when developing services, particularly child care: “sometimes it’s as simple as ensuring that childcare services are included in the services provided to women, or offering them at non-standard hours so that mothers can take advantage of them.”[195]

François Afane, Executive Director of the Conseil de développement économique des Territoires du Nord-Ouest, aptly explained the importance of French-language day care for keeping and attracting young people and families, especially immigrant families, in FMCs, particularly in rural communities:

For us, the early childhood challenge is huge. Families decide to leave our regions because they don’t have access to child care services. We have only one francophone child care centre in Yellowknife. [Its] capacity is 37 spaces, and there are over 50 on the waiting list. That’s just the official list.

If you factor in the other francophone families that send their children to anglophone schools and child care centres, the potential is enormous. We need support and assistance. Children are the future. Once children begin child care in English, they continue their education in English and become completely anglicized.

We need support from the federal government. Early childhood education is vital to the survival of our communities. I only talked about Yellowknife. In other small communities, there aren’t any francophone child care centres at all. Some small communities are dying a slow death because once the children become adults they leave and never return.

Government support would reinvigorate our francophone communities, and also make it possible for families that want to settle and remain in the community do so. That would contribute to retention.[196]

For Affordable Child Care

Mr. Desjardins stressed that access to child care must be affordable. Otherwise, some parents will be at a socioeconomic disadvantage:

[T]here’s the issue of child care affordability. Not all parents can afford to pay extremely high fees to send their children to day care. Some, unfortunately, have to make the choice to stay at home, whether it’s one parent or both. Sometimes, they are single‑parent families. These parents don’t do it by choice, but simply because the fees are really very high.[197]

An Act respecting early learning and child care in Canada includes a day care funding provision for OLMCs.[198] AFFC President Nour Enayeh said that “this [provision]will definitely give francophone women across the country a break so they can focus on their lives and keep working.”[199] The provision meets the expectations of Ms. Boutiyeb, who called for a permanent universal minority language child care program.[200]

Regarding day care, Ms. Pelletier said that some employers are creating workplace day care centres.[201] While at first glance this may appear to be worthwhile, Prof. Vaillancourt said that “it’s not good for society,”[202] since “it hinders worker mobility between employers.”[203] He believes that the government must “improve the availability of child care to encourage worker mobility, as opposed to supporting employer-provided child care programs.”[204]

Government of Canada Support for Minority Language Early Childhood Services

Under the Action Plan for Official Languages 2023–2028, ESDC is managing two new programs directly related to early childhood. The first involves creating a network of early childhood stakeholders and implementing initiatives in FMCs. The second involves training and capacity-building for early childhood educators.[205]

These programs are in addition to the “Support for Early Childhood Development” Program, which was renewed. Between 2018 and 2023, the program created 2,028 child care spaces.[206]

Intergovernmental Cooperation in Early Childhood

Mr. Desjardins touched on the federal-provincial/territorial aspect of managing the availability of early childhood services. He believes that the provinces and territories need to get involved:

[P]rovincial governments need to be at the table as partners, because they’re the ones managing the funds on the ground. If, despite the directions given by the federal government, the funds aren’t managed on the ground in such a way as to make francophone day cares truly accessible, we’re missing the boat.[207]

In short, French-language day care is a vital link in the FMC socioeconomic development chain. As Gaëtan Thomas said, situations like what is happening in Moncton and Fredericton need to be avoided, situations where “more and more francophone parents are having to send their kids to anglophone day care, which is bad. … In urban centres in New Brunswick, many parents have no choice but to send their children to anglophone day care.”[208]

In light of the above, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 16

That the government act and take concrete action to resolve the labour shortage in the field of early childhood and francophone education, as it is an existential challenge to the survival of Francophone communities.

Francophone Immigration as a Driver of Socioeconomic Development

As mentioned earlier, immigration is important for increasing the share of the country’s francophone population and other objectives, such as addressing the labour shortage that hinders the development of sectors that are critical to the vitality of FMCs.

Interdepartmental Cooperation on Francophone Immigration from a Socioeconomic Development Perspective

While Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) is the main federal player with respect to immigration, the cooperation of other federal departments is needed. Some regional development agencies already have working relationships with IRCC so they can help, in their field of expertise, increase francophone immigration.

Mr. Nowlan said that ACOA’s Atlantic Immigration Program had eight employees specifically assigned to support the work of their IRCC colleagues[209]: “We went out to businesses. We talked with businesses and told them this was a great new initiative to use to help attract new immigrants to their business, including in our francophone minority communities. We worked directly with them.”[210]

Mr. Nowlan also explained that some economic immigration projects draw on the expertise of French-language postsecondary institutions to match international students and graduates with local businesses. This tends to encourage international students to stay in the regions where they studied. These programs also benefit employers, who as a result have a greater understanding of the process of hiring immigrants.[211]

Lastly, economic immigration projects help prepare immigrants and their families, thereby promoting settlement and retention:

As you know, when an immigrant comes in, it’s not just about having a person who can turn a screwdriver. It’s about bringing in the whole person and their family, and having an inclusive and diversified work environment. We provide that kind of training to them, with the supports to help them understand what it takes to go through that process.[212]

In light of the above, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 17

That the Government of Canada draw inspiration from the collaboration between Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada and the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency within the Atlantic Immigration Program and extend this model on a national scale to better meet the workforce needs of businesses in francophone minority communities.

Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot

The Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot (RNIP) is another example of interdepartmental and intersectoral work connected to socioeconomic development and immigration.

Covering 11 Canadian regions,[213] the RNIP is an IRCC initiative designed to provide skilled foreign workers with a recommendation to apply for permanent residency. What makes this program unique is that it is “community-driven.”[214] The RNIP is not exclusively for OLMCs. However, candidates must have a certain level of proficiency in one of the official languages. Candidates and their spouses can receive extra points if they demonstrate knowledge of both official languages.

In Northern Ontario, five communities are involved in the pilot: Timmins, Sudbury,[215] North Bay, Thunder Bay and Sault Ste. Marie. According to Nick Fabiano, FedNor has invested in three-year projects for each of those communities.[216]

The RNIP was slated to end in August 2024. However, on 4 March 2024, the Minister of IRCC announced that the RNIP would be made permanent. In the meantime, the department set up two pilot programs, the Rural Community Immigration Pilot and the Francophone Community Immigration Pilot, in autumn 2024.[217]

Immigration to Help Develop Priority Sectors – The Example of Early Childhood

Some witnesses made the connection between immigrant recruitment and labour needs in the early childhood sector.

Like most sectors, early childhood is experiencing a labour shortage. To meet staffing requirements in minority institutions, Daniel Boucher, Executive Director of the Société de la francophonie manitobaine (SFM), said that “one of the things that would be really important is to speed up the certification process for teachers, who come from all over.”[218] Regarding international recruitment, the SFM is urging the Government of Canada to “play a certain role in this area in co‑operation with the provinces, but also with the professional associations.”[219] Specifically, “there needs to be a constant update on the importance of speeding up the accreditation processes so that we can actually get people into the systems, because the current situation doesn’t make sense.”[220]

Some initiatives are already in place. With the support of the Manitoba provincial government, CDEM has set up a targeted recruitment program with a school in Côte d’Ivoire, particularly in early childhood. According to Roukya Abdi Aden, Manager, National Consultation on Economic Development and Employability at RDÉE Canada, they are working together “to facilitate recognition of diplomas so that the transition can be made very quickly.”[221]

It is obvious that RESDAC’s work on credential recognition is an asset for FMCs.

One could look at francophone immigration as a way to fill labour needs in minority institutions such as day cares, but as Mr. Desjardins pointed out, the supply of day care spaces must also be seen as providing an incentive for francophone immigrants to settle and integrate in FMCs:

Immigrants want their children to grow up in French. When they arrive in francophone minority communities outside Quebec, having access to early childhood services in French becomes attractive for them. Among those factors was also the issue of schools. Often, immigrants who settle in regions where French is not the majority language still want the opportunity to raise their children in French. It goes beyond simply speaking French at home.[222]

In its most recent report on immigration in FMCs, the Committee made a recommendation aimed at facilitating recognition of the credentials and skills of francophone immigrants,[223] particularly those working in early childhood. The Committee reiterates its recommendation as follows:

Recommendation 18

That the Government of Canada conduct ongoing negotiations with the provinces and the territories in order to have them recognize foreign credentials, which would, specifically, help francophone newcomers integrate and contribute to the economic development of francophone minority communities.

Immigration to Boost the Population of Rural Francophone Communities

As mentioned earlier, most FMCs are in rural areas, which are seeing declining demographics and economic activity. According to Mr. Deveau, communities of Acadian origin are “losing ground, usually in favour of large urban centres.”[224]

For example, in Nova Scotia, the largest pool of francophones is now in Halifax. Francophones in Halifax have moved there from other provinces, mainly Quebec, but they also come from other countries.