NDDN Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Gaps to Fill: Housing and Other Needed Supports for Canadian Armed Forces Members and their Families

Introduction

During a military career, Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) members and their families typically relocate many times to be on or near military bases and wings (hereafter, military installations). Approximately 10,000 CAF members and their families relocate annually, with 8,000 moving to a different province or territory.[1] In addition to the housing-related challenges experienced when relocating, they–like some other Canadians–may have difficulties accessing adequate and appropriate health care, childcare, education for children, employment for CAF spouses or partners, and support in situations of intimate partner or domestic violence.[2] Moreover, similar to some other Canadians, and although not necessarily limited to situations involving relocation, CAF members and their families may experience homelessness and use food banks.[3]

On 19 October 2023, the House of Commons Standing Committee on National Defence (the Committee) adopted the following motion:

That, pursuant to Standing Order 108(2), the committee undertake a study on the lack of housing availability on or near bases for Canadian Armed Forces members and their families and the challenges facing members and their families when they are required to move across the country; that the committee shall hold a minimum of four meetings for the duration of the study; and that the committee report its findings and recommendations to the House.

Between 30 November 2023 and 10 April 2024, the Committee’s five meetings on this study involved appearances by 10 witnesses: Canadian federal and military officials, an academic, a veteran, a military spouse and others.

This report summarizes witnesses’ comments made to the Committee and relevant publicly available information. The first section highlights challenges experienced in accessing suitable housing, and discusses some of the Department of National Defence’s (DND’s) and the CAF’s housing-related financial supports. The second section outlines relocation-related challenges that CAF members and their families experience, and supports that they can access, in relation to health care, childcare, education for children, spousal or partner employment, intimate partner or domestic violence, and relocation services. The final section contains the Committee’s conclusions and recommendations.

Housing

Witnesses provided the Committee with their observations about access to affordable housing, the DND’s military housing program, military barracks, and housing-related financial supports.

Access to Affordable Housing

Witnesses drew attention to challenges that CAF members and their families experience in accessing affordable housing in Canada. Serge Tremblay, DND’s General Manager of Infrastructure and Technical Services, noted that all Canadians – including these members and their families – are seeking affordable housing, which can be a particular difficulty in Canada’s major urban centres. Similarly, Brigadier-General Virginia Tattersall, the CAF’s Director-General for Compensation and Benefits, said that all Canadians are concerned about access to affordable housing, but also emphasized that “those concerns can be multiplied when a military member is required to relocate for service reasons.” She estimated that CAF members “who live on base are approximately only 20% of the overall Canadian Armed Forces population,” and indicated that most members “live off the base and rent from the economy or actually buy a house, just like any other Canadian would.”

Stating that CAF members and their families relocate “three to four times more often than” non-CAF members and families, Gregory Lick, National Defence and Canadian Armed Forces Ombudsman,[4] underscored that they “must quickly find housing in a new community that they may be unfamiliar with.” He contended that CAF members and their families “are sometimes pushed into either unsafe or unaffordable housing” if they are relocating to a region that lacks affordable housing.

Moreover, Gregory Lick stressed that “lower-ranked [CAF] members and [their] families with special needs or disabilities” are at high risk of not finding affordable housing that meets their specific needs. Consequently, he urged DND and the CAF to implement a “global accommodation strategy” to provide CAF members and their families – including junior CAF members – with military housing units or other accommodation that is suited to their various needs.

Alyssa Truong, a CAF spouse who appeared as an individual, argued that finding affordable and suitable housing in Canada’s current “housing crisis” leads to “extreme stress” for most CAF members and their families, especially when relocating to a region with a high cost of living. In her opinion, access to housing “is one of the most significant stressors” for these members and families, especially for those that have “children with special needs or other complexities.”

Furthermore, Alyssa Truong outlined a number of household income–related and other factors that could affect the ability of CAF members and their families to purchase or rent a house meeting specific requirements when relocating to a different province or territory. Providing an example linked to employment in a provincially and territorially regulated profession, she asserted that “the type of home” that is affordable may be affected if CAF spouses or partners experience difficulties in finding employment in their regulated profession following relocation.

Concerning major urban centres that lack affordable housing, Sergeant (Retired) Christopher Banks, a CAF veteran who appeared as an individual, claimed that junior CAF members usually experience difficulties in accessing affordable housing in those locations. He suggested that such difficulties could exist if those members “don’t already have friends” or family residing in the relevant location, or if they cannot “find a roommate.”

Witnesses also expressed concerns about CAF members and their families that are experiencing homelessness, including because of a lack of affordable housing and a high cost of living. Gregory Lick mentioned that, as the National Defence and Canadian Armed Forces Ombudsman, he “completed 15 full-week visits” to military installations to discuss the challenges that these members and their families experience in relation to housing, health care, childcare, spousal or partner employment, and high living costs. Describing what he learned during those discussions, he indicated that one CAF family “had been homeless for five months” and that several other CAF families either were “one paycheque away from not paying their rent” or were “using food banks.” Gregory Lick also mentioned the following in relation to some CAF members and their families who are experiencing homelessness:

What I am hearing is that some [CAF] members, at different points in time, have been or are homeless. I don’t believe they’ve actually told me what they are living in. They are living in [recreational vehicles] or are couch surfing in some cases. One [CAF family member] told me that they were homeless for five months. They were living somewhere, obviously, but not in a proper home.

Furthermore, Gregory Lick proposed that DND and the CAF should re-evaluate their approach to assessing the nature and extent of homelessness among CAF members and their families. He argued that, although senior CAF members may conduct wellness checks to assess the homelessness being experienced by particular CAF members and their families, some of these members “may be too embarrassed or afraid to tell their leadership” about being homeless. He also suggested that CAF members and their families experiencing homelessness may prefer to report their living conditions confidentially to such entities as the Office of the National Defence and Canadian Armed Forces Ombudsman or the Royal Canadian Chaplain Service. For that reason, Gregory Lick urged DND and the CAF to access multiple sources of information when assessing homelessness among CAF members and their families.

According to Laurie Ogilvie, Senior Vice President of Military Family Services at Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services, temporary homelessness[5] among relocating CAF members and their families may occur while they wait for military housing units or other accommodation. Regarding their permanent homelessness,[6] she stated the following:

I did check with all the [Military Family Resource Centres in Canada] and none of [the centres] that have reported back to me have heard about any families that are permanently homeless.

Finally, witnesses argued that a lack of affordable housing is a factor in the CAF’s ongoing recruitment and retention challenges. In Gregory Lick‘s view, this type of housing challenge can contribute to a CAF member’s decision to leave the military. Similarly, Alyssa Truong contended that some CAF members have “chosen to release [from the CAF]” rather than relocate to a region in Canada where housing is unaffordable.

The Department of National Defence’s Military Housing Program

Witnesses commented on the military housing units that are part of DND’s Military Housing Program, which is implemented by the Canadian Forces Housing Agency (CFHA).[7] Serge Tremblay stated that, as of 30 November 2023, the CFHA managed about 11,600 military housing units, of which 10,000 were occupied by CAF members and their families.

Serge Tremblay referenced the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s 2015 audit of the Military Housing Program, which recommended that DND should identify – as a range – the number of military housing units needed to meet the CAF’s operational requirements. According to him, in 2018, DND said that between 17,000 and 19,000 units were required to provide housing to all CAF members eligible under the Military Housing Program. He confirmed that this estimated range remains unchanged.

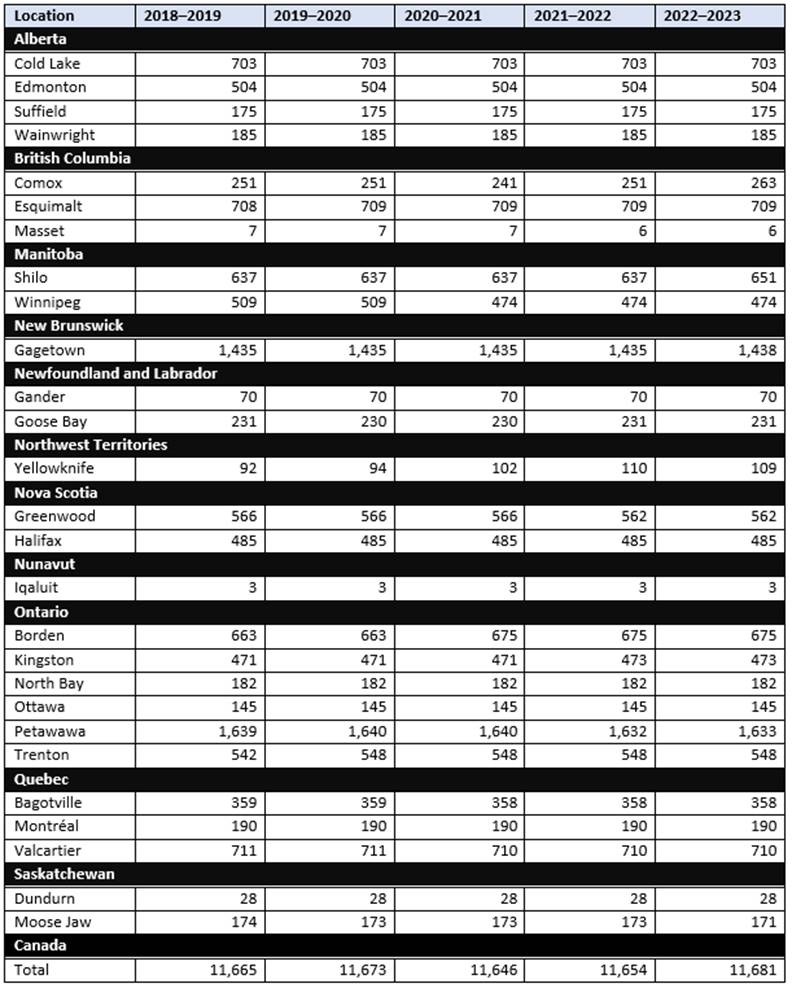

Figure 1 shows the number of military housing units, by location, for the 2018–2019 to 2022–2023 period.

Figure 1—Number of Military Housing Units in Canada, by Location, 2018–2019 to 2022–2023

Sources: Canadian Forces Housing Agency (CFHA), “Housing locations,” Annual Report 2018–2019, 2019; CFHA, “Housing locations,” Annual Report 2019–2020, 2020; CFHA, “About the Agency,” Annual Report 2020–2021, 2021; CFHA, “About the Agency,” Annual Report 2021–2022, 2022; and CFHA, “About the Agency,” Annual Report 2022–2023, 2024.

Witnesses focused on the number of military housing units and associated wait lists. Sergeant (Retired) Banks contended that the number of units available in some regions – such as Ottawa, which had 145 units as of 5 December 2023 – is “insufficient” to meet the growing demand for such units. Moreover, he asserted that, as of that date, there were no military housing units available in Toronto because units in that city had been demolished several years ago and had not been replaced.

Regarding the CFHA’s wait lists for military housing units, Serge Tremblay underlined that “it is standard practice” for the CFHA to “track wait times on an operational basis,” although he also noted that this information is not retained. Furthermore, he pointed out that the wait lists have two priority levels: “priority one” for those relocating in Canada who “have yet to find a house,” and “priority two” for those who have non-Military Housing Program accommodations but who “would like to move into” a military housing unit. Serge Tremblay estimated that, as of 26 October 2023, there were 4,500 CAF members on the wait lists, of which 1,398 – or about 31.1% – were on the “priority one” list.

Concerning the CFHA’s wait lists for military housing units at specific military installations, witnesses drew attention to the reality that the number of CAF members on some of those wait lists is almost the same as the number of units that are available at specific locations. Gregory Lick stated that the number of CAF members who were on the wait lists for Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Edmonton in Alberta and CFB Bagotville in Quebec increased by 261% and 177%, respectively, from 2022 to 2023. He also suggested that, as of 5 February 2024, the number of CAF members on wait lists for CFB Esquimalt in British Columbia, CFB Halifax in Nova Scotia and CFB Trenton in Ontario were almost the same as the number of units at each of these locations.

Moreover, witnesses underscored current federal efforts to increase the number of military housing units, Serge Tremblay and Rob Chambers, DND’s Assistant Deputy Minister of Infrastructure and Environment, outlined the CFHA’s use of its “revenue stream” and of “capital funding” from DND to finance construction and renovation. Serge Tremblay stated that DND allocates capital funding of about $40 million annually to the CFHA. As well, he referred to the CFHA’s implementation of a program to accelerate the construction of new units. That said, Serge Tremblay underlined that – as of 30 November 2023 – the CFHA had constructed fewer than 40 units since 2021.

With a focus on the level of satisfaction that CAF members and their families have with the condition of their military housing unit, Serge Tremblay drew attention to the CFHA’s “cyclical customer satisfaction surveys.” Referencing the results of a CFHA survey, he pointed out that 85% of respondents indicated that they were satisfied with the condition of their unit.

However, Alyssa Truong questioned the accuracy of the results of the CFHA’s customer satisfaction surveys, and particularly mentioned the survey’s methodology. Similarly, in the view of Sergeant (Retired) Banks, certain surveys completed by CAF members – including the CFHA’s customer satisfaction surveys – sometimes do not provide accurate results. He elaborated by stating the following:

When I was still in the military, I was part of a lot of these surveys. … Some of them are done by paper and some of them are done by town halls. … When we do those paper surveys, we [would] get together afterwards and ask each other about [our answers to the questions]. When the eventual report comes out months later and we all get together, we see that the comments we brought up are nowhere to be found in the [survey’s results].

Regarding public–private partnerships aimed at increasing the number of military housing units, Serge Tremblay mentioned that the CFHA is “looking to try to partner” with firms in Canada’s housing sector to construct units. According to Rob Chambers and Serge Tremblay, the CFHA recently issued Requests for Information that will allow it to consider options for addressing the current shortage in units. Rob Chambers also indicated that the CFHA is working with “landlords and landowners” in the country’s housing sector to locate suitable accommodation for CAF members and their families.

Furthermore, Rob Chambers highlighted the CFHA’s ongoing cooperation with the Canada Lands Company and with Public Services and Procurement Canada to assess the potential for repurposing underused federal properties to construct military housing units. In particular, he noted that DND and the CFHA are “working very closely” with the Canada Lands Company to “identify surplus [federal] properties … that would lend themselves to housing.” As well, Rob Chambers indicated that, because the Canada Lands Company and Public Services and Procurement Canada have “commercial authorities,” they could enter into a public–private partnership with Canada’s housing sector on behalf of DND and the CFHA to acquire housing units for CAF members and their families.

Witnesses also identified additional measures that DND and the CFHA could implement to increase the number of military housing units and other accommodation on or near military installations for CAF members and their families. Gregory Lick proposed that DND and the CFHA could work with municipal authorities, highlighting that – during a recent meeting in Greenwood, Nova Scotia – municipal representatives expressed an interest in cooperating with the federal government to assess the possibility of transferring unused municipal lands to DND and the CFHA for the construction of units.

Sergeant (Retired) Banks called for a “surge in federally built houses and apartments on bases, such as what Canada did when soldiers returned from the Second World War.” He also suggested that underused “federally owned office buildings” in major urban centres should be converted into apartment-style military housing units or other forms of accommodation for CAF members and their families.

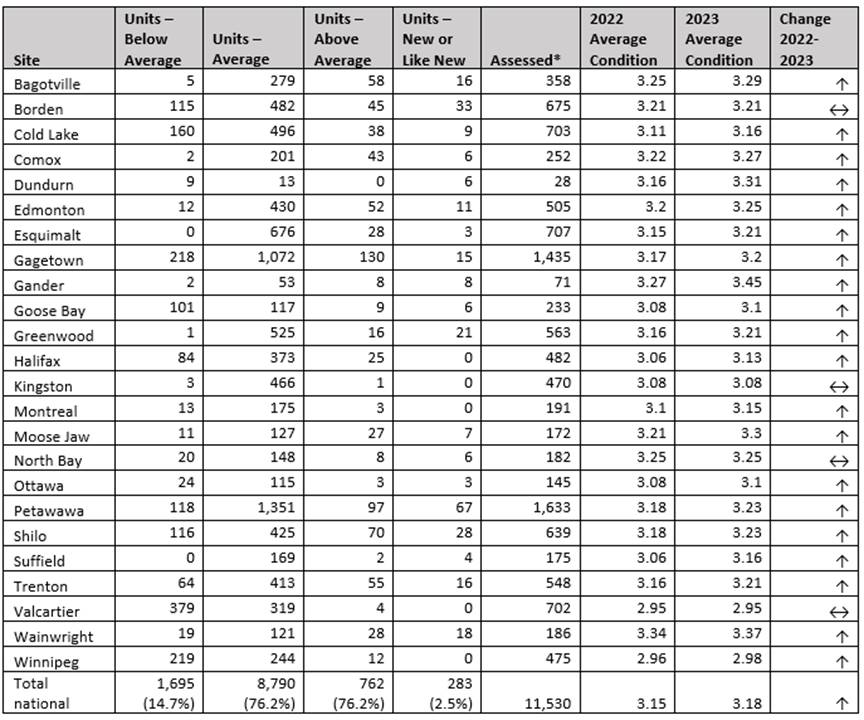

As well, witnesses commented on the condition of the CFHA’s existing military housing units. Serge Tremblay highlighted that the number of units in “below average” condition has fluctuated in recent years, rising throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and then falling after the pandemic ended. He stated that, to comply with public health measures designed to prevent and control the spread of the COVID-19 virus, the CFHA “minimized the amount of time” spent repairing or renovating older units during the pandemic, leading to “some degree of degradation.” Moreover, Serge Tremblay said that most units – including those that are new – have “continued to age, regardless of the pandemic.” He added that several units that were built in 2015–2016 with increased federal funding are currently in “average” condition.

Sergeant (Retired) Banks contended that most of the CFHA’s military housing units were constructed in the 1950s and the 1960s, and he asserted that these older units tend to “lack modern insulation, heating [and] wiring,” and need extensive repairs or renovations. Sergeant (Retired) Banks also argued that some units are unoccupied because they are “awaiting repairs or demolition.”

Alyssa Truong suggested that the condition of the CFHA’s military housing units can vary by location. She mentioned that she lived in a “fully renovated” unit in “above average” condition at CFB Greenwood in Nova Scotia and currently resides in a unit of “average” condition at CFB Borden in Ontario, with “sewage backups,” a broken furnace and “hot water issues.” In Alyssa Truong’s opinion, despite the CFHA’s ongoing efforts to improve the condition of the units at CFB Borden, there are still “lots of unrenovated” units, including some that have “paint chipping off [kitchen walls] into dishes” or warnings about the existence of potential health hazards.

Furthermore, Alyssa Truong described the impacts that the condition of the CFHA’s military housing units can have on the health and well-being of CAF members and their families, contending that older units that have “mould or poor ventilation” can be a health risk to individuals with underlying health conditions and can contribute to other health challenges. She also asserted that, because the CFHA’s wait lists usually operate on a “first-come, first-served” basis, the CFHA does not always provide units that are suitable for those who have medical or other needs that require special supports or structural adjustments.

In 2023, the CFHA assessed the condition of the 11,530 military housing units in 24 locations across Canada. Figure 2 shows the results of this assessment, indicating the number of units that were identified to be in “below average,” “average,” “above average,” and “new or like new” condition. It also presents, by location, the average condition rating in 2022 and 2023 for those units, as well as the change in that rating between those two years.

Figure 2—Canadian Forces Housing Agency Condition Assessment Summary (April 2023)

Source: Canadian Forces Housing Agency, “3.3 Departmental Results Framework,” Annual Report 2022–2023, 2024, p. 15–16.

Witnesses also provided their observations about the CFHA’s approach to allocating military housing units, which is based on family size. Serge Tremblay said that, when CAF members accept a unit, “what they have in mind is the smallest layout that will meet their needs at the time they take possession of the house.” However, he also observed that family size or composition can change over time, with the result – for instance – that the unit may not always have enough bedrooms.

Gregory Lick noted that a 2022 report[8] by the Office of the National Defence and Canadian Armed Forces Ombudsman identified the need for DND and the CAF to modernize their definition of the term “military family” to reflect the evolving composition and needs of CAF members and their families. In his view, some CAF families “tak[e] care of more elderly parents,” others have one parent and still others have children with special needs. He argued that, whenever possible, CAF members and their families should be provided with housing that meets their specific requirements.

As well, witnesses mentioned the CFHA’s use of private-sector contractors to maintain and renovate some of its military housing units. Rob Chambers contended that, before hiring contractors, the CFHA assesses whether they are needed to conduct maintenance or whether DND personnel can complete that work “in‑house.”

Sergeant (Retired) Banks alleged that several private-sector contractors have been involved in acts of “corruption,” including by not finishing the renovations that they started on certain military housing units or other accommodation used by CAF members and their families. He also claimed that, although some contractors are “blacklisted because of … poor performance,” they are “sometimes hired to do the same terrible job all over again.” Moreover, Sergeant (Retired) Banks suggested that, instead of contractors, the CFHA should have DND personnel or other public servants perform most maintenance and renovation tasks in relation to its units.

Furthermore, witnesses commented on the need for all of the CFHA’s military housing units to be located in areas where there is adequate infrastructure. According to Gregory Lick, DND and the CFHA “simply do not have the resources in various areas, including the infrastructure on base.” With a focus on newly constructed military housing units located on or near military installations, Serge Tremblay indicated that DND and the CFHA are working with municipal authorities to ensure that those units are co-located with adequate and modern infrastructure, including electrical power generation.

Finally, witnesses discussed DND’s recent decision to increase 2024–2025 rental costs for the CFHA’s military housing units by a national average of 4.2%.[9] Gregory Lick asserted that it is “a bit tone deaf” for DND to increase rental costs at a time when many CAF members and their families are experiencing a lack of access to affordable housing and high costs of living. Gregory Lick urged DND to reverse this decision as a “viable solution” to helping members and their families afford the CFHA’s units.[10]

Military Barracks

Witnesses pointed out that CAF members may live in military barracks. Sergeant (Retired) Banks noted that CAF members can live in barracks permanently or temporarily. Regarding temporary accommodation, he said that members of the CAF’s Primary Reserve Force may live in barracks when participating in training or when deployed to support the CAF’s domestic operations.

As well, witnesses made comments about the condition of military barracks. Gregory Lick suggested that some barracks require extensive repairs or renovation. He indicated that CAF members have sent photos to the Office of National Defence and Canadian Armed Forces Ombudsman that show mould growing on walls and ceilings in some barracks, as well as “toilet facilities [that are] not up to standard.” Gregory Lick added that, although military barracks “are not five-star hotels,” he does not “expect that any [CAF] member would live in those conditions.” He also indicated that he has discussed deteriorating living conditions in barracks with DND and the CAF. Furthermore, Sergeant (Retired) Banks agreed that some barracks are in “poor repair.” He asserted that, while training, he lived in barracks at a number of military installations that had “broken [water] faucets,” as well as asbestos in floor tiles and elsewhere.

Finally, witnesses mentioned the number of military barracks. Sergeant (Retired) Banks argued that more barracks are needed, including for Primary Reserve Force members. He contended that, “when reservists arrive en masse to a base or training centre for months of training,” they are often told that “there aren’t enough rooms available” in the barracks. According to him, the lack of available barracks can lead some members to “spend the sweltering summer or frigid winter in a tent.”

Financial Supports

Witnesses provided their observations about military housing allowances and other financial supports, including the monthly Canadian Forces Housing Differential (CFHD) that replaced the monthly Post-Living Differential (PLD) on 1 July 2023.[11] Brigadier-General Tattersall described the CFHD as a “payment designed specifically to assist those who need some financial assistance to secure suitable housing.” As well, she highlighted the monthly Provisional Post-Living Differential that was implemented on 1 July 2023 as a temporary housing allowance – available until 1 July 2026 – for eligible CAF members who experienced a reduction in the amount of their monthly housing allowance as part of the transition from the PLD to the CFHD.[12]

Gregory Lick expressed support for the CFHD as a replacement for the PLD, suggesting that – unlike the PLD’s rates, which were not adjusted regularly to reflect changing economic conditions[13] – the CFHD’s rates are “supposed to be updated every year.” However, Sergeant (Retired) Banks contended that some CAF members who were receiving the PLD have been negatively affected by implementation of the CFHD, and added that eligibility for the CFHD may end if CAF members receive a salary increase that makes them ineligible.[14]

Witnesses also focused on financial supports available to relocating CAF members for costs associated with the sale and purchase of a primary residence, such as real estate fees and land transfer tax. Brigadier-General Tattersall indicated that DND and the CAF offer three financial supports: the Temporary Dual Residence Assistance for eligible CAF members who own a primary residence and a secondary residence; the Real Estate Incentive for eligible relocating CAF members who decide not to sell their primary residence after moving to another residence; and the Home Equity Assistance support for eligible relocating CAF members who experience a financial loss when they sell their primary residence.[15]

Concerning the Home Equity Assistance support, Brigadier-General Tattersall said that DND and the CAF reimburse up to $30,000 for eligible relocating CAF members who sell their primary residence at a price that is lower than that residence’s purchase price. However, she acknowledged that this maximum amount may not fully compensate CAF members who sell their primary residence at a loss. Focusing on Alberta, Gregory Lick suggested that some CAF members and their families living in that province have experienced a financial loss of up to $100,000 when selling their primary residence because of “housing market fluctuations related to oil patch financial ups and downs.”

Relocation Challenges Other Than Housing

Witnesses provided comments to the Committee about some challenges that CAF members and their families experience, and supports that are available, when relocating in Canada. In particular, they mentioned health care, childcare, education for children, spousal or partner employment, intimate partner or domestic violence, and relocation services.

Health Care

Witnesses drew attention to challenges that CAF families may experience with provincial and territorial health care systems (hereafter, civilian health care systems).[16] Gregory Lick suggested that accessing adequate health care is a concern for all CAF families when relocating to a different province or territory.

Shannon Hill, a Ph.D. candidate at Queen’s University who appeared as an individual, contended that CAF families do not have access to a “dedicated” health care system, and asserted that – like non-CAF families – CAF family members may experience long wait times before seeing a physician or other health care provider in a civilian health care system. According to her, while they are on a wait list to see a health care provider, some CAF family members “may have to relocate,” which leads to them “starting this process all over again” at their new location.

In Alyssa Truong‘s view, CAF families – including those with children who have special medical needs – may experience long wait times before receiving health care services in a civilian health care system if they are unable to secure housing prior to moving to a different location. She claimed that a CAF family member’s access to such services “may be delayed” until the family has “a legal address.”

Witnesses also identified initiatives designed to help CAF family members access health-related services. Brigadier-General Tattersall said that Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services’ Military Family Virtual Healthcare Program and Maple, a network of Canadian-licensed physicians and nurse practitioners, cooperate to provide CAF family members – including those who are relocating in Canada – with access to telemedicine services. She noted that telemedicine “permits [these] members who may not yet have a family doctor to be able to access medical advice and to obtain prescriptions and lab or imaging requisitions.” Laurie Ogilvie observed that, in 2023, approximately 7,300 CAF family members used this telemedicine service.

Finally, Laurie Ogilvie also stated that CAF family members can access a number of health-related initiatives in addition to the telemedicine service. According to her, these initiatives include “emergency family care assistance,” Calian Health’s Military Family Doctor Network, children and youth mental health counselling services, a “24-7” crisis and referral line, and Kids Help Phone crisis text services. Moreover, she indicated that Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services offers financial support to CAF family members who may have to travel long distances to access a health care provider.

Childcare

Witnesses focused on some childcare-related challenges that CAF members and their families experience when relocating in Canada, including access. Alyssa Troung described a lack of access to childcare as a “significant issue” for most CAF families with children, and contended that – as a result – a CAF spouse or partner may decide to forego paid employment, with potentially negative impacts on household income. Moreover, she asserted that – like other Canadian families with children – CAF families requiring childcare may be added to a provincial or territorial wait list because there are “simply not enough child care spots” in Canada.

In the view of Sergeant (Retired) Banks, a lack of access to affordable childcare may lead a CAF family to live in separate locations, especially if the family has a child with special medical needs. He mentioned that he served alongside a CAF member who relocated without his family because the location of his new posting did not have adequate childcare and other services required to meet the special needs of his two children.

As well, witnesses highlighted measures aimed at supporting CAF members and their families seeking childcare in a new location. Laurie Ogilvie drew attention to Seamless Canada, through which DND, the CAF and Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services cooperate with provincial and territorial governments to improve access to childcare, as well as education for children, and spousal or partner employment, for relocating CAF families. She also said that Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services’ Emergency Family Care Assistance provides these families with financial or other supports relating to childcare, and observed that certain Military Family Resources Centres offer childcare to such families.

Finally, Allysa Troung stressed that the childcare services available to CAF members and their families can vary across military installations. She added that “[s]ome [CAF] bases have larger child care centres than others,” and commented that certain – but not all – such installations “offer emergency child care.”

Education for Children

Witnesses outlined a number of education-related challenges affecting the children of CAF members (hereafter, CAF members’ children) who relocate in Canada. Sergeant (Retired) Banks argued that access to, and the quality of, the education available to these children “can be less than stellar depending on the posting.”

In Shannon Hill‘s view, frequent relocations can affect “the educational experiences of military-connected children and youth” because CAF members’ children could have multiple transitions “between schools and across education systems.” Moreover, she said that some of these children may relocate prior to completing the school year, leading to their withdrawal from such extracurricular activities as social clubs and sport teams.

Furthermore, Shannon Hill contended that provincial and territorial education systems vary in their curriculums and other standards, with potentially negative impacts on CAF members’ children who are relocating to a different province or territory. She elaborated by stating the following:

Academically, military-connected students may experience challenges such as curricular gaps and/or redundancies, particularly if they relocate across jurisdictional boundaries where differing standards and requirements exist. Given differences in standards and requirements across education systems, entry into school as well as post-secondary opportunities for military-connected students can be impacted.

As well, Shannon Hill argued that CAF members’ children who are relocating and who “require access to special education services” may find that needed services are unavailable in certain regions in Canada, especially in “isolated or rural locations.” She added that these children may have to adapt to different “special education systems” when relocating to another province or territory.

Witnesses also drew attention to challenges that CAF members’ children who are relocating may experience in accessing schools that provide education in their primary language. Laurie Ogilvie underlined that these children who are francophone may experience difficulties in accessing French-language schools if their families relocate to a predominantly anglophone location. Shannon Hill made similar comments regarding such children who are anglophone and who relocate to communities in Quebec that have a limited number of English-language schools. Moreover, Shannon Hill asserted that CAF families that prefer schools offering French immersion programs may move to a city or town that “only [has] one school that offers French immersion.”

As well, witnesses described education-related financial and other supports provided to CAF members’ children, including those relocating in Canada. According to Laurie Ogilvie, Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services offers counselling services to help with accessing education in these children’s primary language. Additionally, she remarked that Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services offers language training programs to CAF family members, including children: Pour l’amour du français and For the Love of English. Furthermore, Laurie Ogilvie referenced Support Our Troops’ National Scholarship Program, which provides scholarships to eligible CAF members’ children pursuing post-secondary education.

Additionally, witnesses advocated further research about the educational experiences of CAF members’ children, including when they relocate in Canada and abroad. Shannon Hill argued that Canadian research about “the educational experiences of military-connected children and youth” is currently lacking. She called for increased federal funding to support academic researchers studying these experiences, with the results then informing the design and implementation of federal measures and supports to address these children’s education-related challenges.

Moreover, witnesses discussed the impacts of ongoing relocations on CAF members and the well-being of their children. Shannon Hill contended that there is a constant need for these children to develop new social circles and adapt to unfamiliar environments, with perhaps particular challenges for adolescents because of “the important role [that] peer networks play in adolescent development.” That said, she also claimed that continuous relocations may have positive impacts, leading to opportunities to make new friends and travel to different locations. Shannon Hill mentioned that, as she was growing up in “a military family,” she “met so many incredible people whom I’ve stayed in touch with.” As well, Shannon Hill said that she has met CAF members’ children who have “talked about being proud of living in a military family,” despite the challenges when relocating.

Recognizing the social and academic impacts of relocations, Shannon Hill also urged DND and the CAF to reduce the number of relocations for CAF families that have children with special medical needs or that have children who are adolescents.

Finally, with a focus on the CAF’s recruitment and retention challenges, Shannon Hill highlighted that a 2013 report by the Office of the National Defence and Canadian Forces Ombudsman identified “child and youth education” as a factor contributing to a CAF member’s decision to leave the military.[17]

Spousal or Partner Employment

Witnesses drew attention to employment-related challenges that CAF spouses or partners may experience when relocating in Canada. Gregory Lick suggested that these spouses or partners may be temporarily or permanently unemployed, including because they may “take a break from paid work to settle their family in a new community.” He added that such unemployment “exacerbates the financial uncertainties for [some CAF] families.”

As well, witnesses discussed relocating CAF spouses or partners employed in a provincially and territorially regulated profession. Alyssa Truong pointed out that these spouses or partners may work in such provincially and territorially regulated professions as health care provider, counsellor, early childhood educator or social worker. Gregory Lick said that they may experience unemployment or underemployment if they relocate to a province or territory that does not recognize their professional qualifications, leading some to seek employment in sectors unrelated to their education or past employment. He encouraged DND and the CAF to work with provincial and territorial governments to “provid[e] equivalencies” regarding professional qualifications and thereby facilitate an ability to work in any province or territory.

Witnesses also outlined some employment-related supports available to CAF spouses or partners, including those who are relocating. Brigadier-General Tattersall commented that Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services organizes virtual career and networking fairs, as well as other events. She observed that about 120 spouses or partners and 14 employers attended three events held in fall 2023. Moreover, she indicated that Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services offers online career counselling to CAF spouses or partners.

Finally, Laurie Ogilvie noted that Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services’ Military Spousal Employment Network assists CAF spouses or partners – relocating and otherwise – in their efforts to find employment, including in professions with high wages and opportunities for career advancement. Moreover, she stated that Canadian Forces Morale Welfare Services employs these spouses or partners, adding that approximately 14% of its workforce comprises such individuals.

Intimate Partner or Domestic Violence

Witnesses made comments about the challenges that CAF family members affected by intimate partner or domestic violence (hereafter, affected persons) may experience when relocating in Canada. Gregory Lick indicated that incidents of such violence “do tragically occur” in certain CAF families, and noted that a number of military installations offer temporary housing to affected persons. Alyssa Troung contended that the perpetrator of intimate partner or domestic violence may be a CAF member who rents the military housing unit where the affected person lives.

As well, Alyssa Truong asserted that an affected person may be unable to leave an abusive relationship with a CAF member if there is a situation of financial dependence or an inability to secure affordable housing. Alyssa Truong added that there may be a “cycle of abuse,” and she maintained that some affected persons may have children with the perpetrator, resulting in the need to “make difficult decisions with regard to custody arrangements.”

With a focus on affected persons who are women, Alyssa Truong suggested that access to adequate social support services may be lacking or women’s shelters may be located far from military installations. Concerning CFB Borden, she stated the following:

In Borden the closest women’s shelter is about 25 minutes away. That includes needing a vehicle. You can’t walk. Oftentimes, these barriers to seeking social assistance are greater. It’s been my personal experience that individuals just simply stay within the family home in a potentially dangerous situation.

Finally, Alyssa Truong called on DND and the CAF to develop guidelines and implement measures to address the various challenges that affected CAF members and their families experience when relocating in Canada.

Relocation Services

Witnesses highlighted that private-sector firms are contracted to provide relocation services to CAF members and their families. Brigadier-General Tattersall remarked that this “outsourc[ing]” started in 1998, and stated that DND and the CAF currently lack the personnel and other resources needed to provide relocation services to CAF members. Consequently, she stressed that “it’s a bit of a myth to think that [DND and the CAF] could deliver the same scale of services that [CAF members and their families] currently receive” from such firms as SIRVA Worldwide, Inc. and BGRS.[18]

Robert Olmsted, President of Global Relocations at SIRVA Worldwide, Inc., asserted that all of SIRVA Worldwide, Inc.’s contracts with DND and the CAF for providing relocation services have been “awarded through open and competitive bid processes and include rigorous oversight and high performance standards.” Furthermore, he added that two contracts were awarded to BGRS: one in in 2009 and the other in 2016.

Witnesses described the relocation services that SIRVA Worldwide, Inc. provides to relocating CAF members and their families. Robert Olmsted said that these services include “initial consulting and guidance” – including briefings – before the move, and “a range of on-the-ground services from origin to destination that help individuals and families as they settle into their new homes.” He noted that these briefings provide CAF members with information about the services to which they are entitled and the costs that will be borne by SIRVA Worldwide, Inc.

Robert Olmsted also indicated that SIRVA Worldwide, Inc. provides financial supports to relocating CAF members and their families. According to him, these supports include an advance of funds for anticipated relocation-related costs. Moreover, he remarked that SIRVA Worldwide, Inc. provides informational resources about real estate firms and facilitates access to moving firms.

Highlighting SIRVA Worldwide, Inc.’s efforts designed to enhance its relocation services, Robert Olmsted drew attention to the reinstatement of in-person briefings for relocating CAF members. He mentioned that those briefings, which had been eliminated in 2017, were reinstated after relocating members expressed concerns about “the lack of [such] briefings taking place on [military] bases.” As well, Robert Olmsted observed that SIRVA Worldwide, Inc. has implemented an “electronic fund transfers” option for the financial supports it provides.

With a focus on the level of satisfaction among relocating CAF members and their families regarding SIRVA Worldwide, Inc.’s services, Robert Olmsted indicated that customer satisfaction surveys are not conducted. That said, he noted that SIRVA Worldwide, Inc. uses metrics to assess the quality of its relocation services, including by determining the number of inquiries that relocating CAF members and their families submit about the delivery and availability of services. He estimated that, “each month, about 7,000 to 9,000 inquiries come in from military members.” As well, Robert Olmsted asserted that SIRVA Worldwide, Inc. calculates the amount of time that its personnel spend responding to those inquiries.

Witnesses also underscored the cyber attack against SIRVA Worldwide, Inc. and BGRS that occurred in fall 2023. Brigadier-General Tattersall emphasized that the cyber attack was worldwide, affecting operations in Canada and foreign jurisdictions. She also stressed that CAF members and their families continued to relocate despite the cyber attack.

According to Robert Olmsted, the cyber attack “disrupted access to certain of [SIRVA Worldwide, Inc.’s and BGRS’s online] platforms and resulted in unauthorized access to information belonging to current and past clients and their employees.” Robert Olmsted stated that the cyber attack occurred on 28–29 September 2023, and he added that the attack was reported to DND, the CAF and other relevant federal entities on 3 October and again on 4 October 2023.

Furthermore, Robert Olmsted mentioned that the perpetrators of the cyber attack copied some data maintained in certain databases and encrypted internal systems belonging to SIRVA Worldwide Inc. and BGRS. Regarding the access that the perpetrators had to SIRVA Worldwide, Inc.’s and BGRS’s databases, he said the following:

We maintain data, in our databases that were not compromised, relating to our process of moving people. The data that was compromised included unstructured files, spreadsheets, Word documents and things like that … . However, we do maintain data relating to people’s addresses, because we’re moving them and things like that.

As well, Robert Olmsted highlighted the following:

The databases I was referring to are the databases in which we store our operating data. They were not compromised, to be very clear. Those databases that had our structured data relating to our customers and clients were not compromised.

The data that was compromised was spreadsheets and what we and the experts refer to as “unstructured data” that was in shared drives and things like that. The difference is that the actual databases in which we have all the data we work with day to day in our systems were not compromised.

Finally, Robert Olmsted mentioned that, as of 31 January 2024, SIRVA Worldwide, Inc. and BGRS were continuing to assess the cyber attack’s impact on their operations, online platforms and databases, as well as on their clients’ personal information. He also indicated that, following the cyber attack, SIRVA Worldwide, Inc. and BGRS were able to restore the functions of their online platforms, including websites that were not operational during the attack.

The Committee’s Conclusions and Recommendations

At present, many Canadians are experiencing challenges. Access to affordable housing, long wait times for health care and perhaps for childcare, a generally high cost of living, homelessness and the use of food banks are difficulties that exist throughout the country. However, these difficulties can present particular challenges for CAF members and their families. Members experience mandatory relocations, their children have to adapt to different curriculums and other education-related standards if relocating to another province or territory, and certain locations may have limited employment opportunities for spouses or partners.

Some CAF members live in military housing units with their families, while others may reside alone in military barracks. Still others live in the same types of accommodation as other Canadians. The number of units and barracks is insufficient, and their condition can vary due to such factors as age, and the nature and extent of maintenance over time. To address the shortage of units and barracks, and to ensure safe living conditions, there are opportunities for the federal government to collaborate with relevant other entities to support CAF members as they seek suitable accommodation, including military housing units or military barracks.

A range of housing-related financial supports, including housing allowances, are available to help CAF members access suitable housing. As well, relocating CAF members can receive support to help them meet the costs associated with the sale and purchase of a primary residence. However, recognizing that accommodation costs and CAF members’ needs change over time, there would be benefits to examining – on a periodic basis – the federal housing-related financial supports for CAF members to ensure that the goals for that support are being met.

In addition to the housing challenges that CAF members and their families may experience as they move to various locations – perhaps from one province or territory to another – throughout a military career, they may have other difficulties. They include accessing timely and/or suitable health care, childcare, education for children, spousal or partner employment, support in situations of intimate partner or domestic violence, and information concerning the relocation services provided by SIRVA Worldwide, Inc. and BGRS.

For example, some CAF family members currently wait a considerable period of time before accessing care in civilian health care systems, and they may have difficulties securing affordable childcare. As well, CAF members’ children may be unable to receive education in their primary language, and CAF spouses or partners may experience unemployment and underemployment, especially if they are in a provincially and territorially regulated profession. Moreover, social support services for CAF families affected by intimate partner or domestic violence may be inadequate or difficult to access. As well, some relocating CAF members and their families may not experience a seamless relocation, notwithstanding the private sector–provided services. In each of these areas, federal, provincial and territorial governments and other stakeholders could collaborate on options for resolving challenges.

The Government of Canada has taken actions to address certain housing- and relocation-related challenges affecting CAF members and their families, but gaps remain. In that context, the Committee recommends the following:

Recommendation 1

That the Government of Canada reverse the April 1, 2024 on-base rent increase.

Recommendation 2

That the Government of Canada take any necessary steps to preemptively vet any third party contractors responsible and eliminate alleged corruption among contractors hired for facility maintenance and housing renovations of Canadian Forces Housing Authority (CFHA) units.

Recommendation 3

That the Government of Canada allocate adequate resources to bring existing Canadian Armed Forces’ facilities and housing units up to federal health and safety building standards, as well as construct and maintain the necessary number of barracks and residential housing units (RHUs) for each base.

Recommendation 4

That the Government of Canada determine an alternative means of surveying members to form an estimate of how many are unhoused, “living rough,” or remaining in precarious relationships for the purpose of securing housing, without exposing affected members to embarrassment or stigma.

Recommendation 5

That the Government of Canada identify and remedy factors in the procurement and contracting process, which results in potentially lapsed funding for facility and housing upkeep and renovation.

Recommendation 6

That the Government of Canada regularly track the number of housing units, wait times, shortages, and satisfaction of military members, and report these numbers annually in the Departmental Results Report.

Recommendation 7

That the Government of Canada restore the maximum compensation to military members who sell their homes at a loss from 80% of the reimbursable amount or $30,000, whichever is less, to the 100% Home Equity Assistance reimbursement that was policy under the Canadian Forces Integrated Relocation Program prior to April 19, 2018.

Recommendation 8

That the Government of Canada dedicate more federal land and properties to be used to expand military housing to reduce the waitlist for military housing on base.

Recommendation 9

That the Government of Canada develop plans to renovate and expand older housing stock, including residential housing units (RHUs) and barracks, to meet housing demand on base and ensure they can be inhabited year round.

Recommendation 10

That the Government of Canada mandate that all contractors are required to immediately notify the government when there is a cyber attack that results in a breach of personal sensitive information.

Recommendation 11

That the Government of Canada implement Recommendations 7 and 32 from the Standing Committee on National Defence report Canadian Armed Forces Health Care and Transition Services.

Recommendation 12

That the Government of Canada give greater consideration to military families with health concerns when deciding to repost military personnel and when providing military housing.

Recommendation 13

That the Government of Canada work with provinces and territories to develop a program, to create national testing standards for regulated professions, to ensure that military spouses and all certified workers are eligible to work in any province or territory.

Recommendation 14

That the Government of Canada review the frequency of transfers in order to limit their impact on families, spouses and housing availability.

Recommendation 15

That the Government of Canada increase funding for the construction of new housing units for CAF members or CAF members and their families in order to ensure the availability of 17,000 to 19,000 military housing units that are needed to meet the CAF’s operational needs.

Recommendation 16

That the Government of Canada ensure that French schools are available near military bases.

Recommendation 17

That the Government of Canada fund research on the educational experiences of CAF members’ children to inform the design and implementation of federal measures and supports to address these children’s education-related challenges.

Recommendation 18

That the Canadian Armed Forces Real Property Operations Group perform a Value-For-Money analysis on all maintenance and service contracts and maintain a centralized database of contractor’s performance to inform future contracts.

Recommendation 19

That the Canadian Armed Forces Real Property Operations Group and the Department of National Defence end their contracts with consultants who have conflicts of interest with other major private developers.

Recommendation 20

That the Government of Canada end the outsourcing of relocation services for Canadian Armed Forces members and return it to delivery by public servants.

Recommendation 21

That the Government of Canada support military families seeking employment by abolishing the exclusion order SOR/82-361a that excludes the Staff of Non-Public Funds, and by paying fair public servant wages to these staff.

Recommendation 22

That the Government of Canada enact all recommendations from the National Defence and Canadian Armed Forces Ombudsman’s 2022 report, Service Versus Self.

Recommendation 23

That the Department of National Defence collaborate with municipalities to develop non-profit and cooperative housing near military bases.

Recommendation 24

That the Government of Canada consider providing relocation services for civilians married to, in a common-law or committed relationship with a military member upon separation.

Recommendation 25

That the Government of Canada conduct an audit of Salary Wage Envelope funding and the overreliance on contractors for facilities maintenance.

[1] Lynda Manser, “The state of military families in Canada: a scoping review,” Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health, Vol. 6, No. 2, August 2020, pp. 120–128.

[2] In November 2023, the House of Commons Standing Committee on National Defence (NDDN) released a report addressing health care and transition services in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF), as well as challenges that CAF families experience in accessing health care, childcare, and spousal and partner employment. See House of Commons, Standing Committee on National Defence, Canadian Armed Forces Health Care and Transition Services, 44th Parliament, 1st Session, November 2023. Regarding intimate partner or domestic violence, see Alla Skomorovsky, FIlsan Hujaleh and Stefan Wolejszo, “Intimate Partner Violence in the Canadian Armed Forces: Psychological Distress and the Role of Individual Factors Among Military Spouses,” Military Medicine, Vol. 182, No. 1–2, January–February 2017, pp. 1568–1575.

[3] In December 2023, witnesses told the Nova Scotia Legislature’s Standing Committee on Veterans Affairs that some CAF Regular Force members serving in Halifax may experience homelessness and use food banks. See Nova Scotia Legislature, Standing Committee on Veteran Affairs, Transcripts, 19 December 2023.

[4] Gregory Lick served as the National Defence and Canadian Armed Forces Ombudsman until July 2024, when Robyn Hynes became the interim National Defence and Canadian Armed Forces Ombuds. See Office of the National Defence and Canadian Armed Forces Ombudsman, Previous Ombuds.

[5] The term “temporary homelessness” refers to situations in which an individual experiences homelessness over a period of less than six months and fewer than three episodes of homelessness during a year. In certain cases, an individual experiencing temporary homelessness may lack access to housing for less than a month and “will manage to leave homelessness on their own, usually with little support.” See Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada, “The experience of homelessness,” Homelessness Partnering Strategy Coordinated Canadian Point-in-Time Counts, 2016; and Havi Echenberg and Laura Munn-Rivard, Defining and Enumerating Homelessness in Canada, Library of Parliament, Publication No. 2020-41-E, 18 December 2020.

[6] The term “permanent homelessness,” or “chronic homelessness,” refers to situations in which an individual who has been “homeless for at least 180 days at some point over the course of a year (not necessarily consecutive days);” and/or may experience “[r]ecurrent episodes of homelessness over three years that total at least 18 months.” See Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada, “2. Definitions,” Reaching Home: Canada’s Homelessness Strategy Directives, 2024.

[7] Before 1995, each Canadian Army base, Royal Canadian Navy base and Royal Canadian Air Force wing managed military housing units located on or near their respective military installations. In 1995, the Canadian Forces Housing Agency (CFHA) was created as a “provisional special operating agency” of the Department of National Defence (DND) with a mandate to provide housing services to CAF members and their families, and to manage and maintain DND’s military housing units. In 2004, the CFHA was given a permanent status. See DND, Canadian Forces Housing Agency Annual Report 2021–2022; and Office of the Auditor General of Canada, “Report 5 – Canadian Armed Forces Housing,” Fall 2015: Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, 2015.

[8] See Office of the National Defence and Canadian Armed Forces Ombudsman, Service Versus Self, 2 May 2022.

[9] For more information, see DND, “What is the percentage shelter charge increase across Canada for Fiscal Year (FY) 2024–2025?,” Shelter charge (rent) adjustment.

[10] On 7 February 2024, NDDN adopted the following motion in relation to DND’s decision to increase rental costs for military housing units: “Given that, rent for Canadian military personnel living on bases is increasing this April, and at a time when the military is struggling to recruit and retain personnel, the committee report to the House, that the government immediately cancel all plans to increase rent on military accommodations used by the Department of National Defence.” See NDDN, Increase in Rental Housing Costs for Canadian Military Personnel, 7 February 2024.

[11] Until July 2023, eligible CAF members received an allowance through the Post-Living Differential (PLD) to minimize negative financial impacts associated with being posted to a location with a high cost of living. The PLD’s rates were based on a comparison of multiple living costs – including housing, groceries, transportation and childcare – in a specific location to those costs in Ottawa–Gatineau. The Canadian Forces Housing Differential’s (CFHD’s) rates are calculated using a “comparator value” that represents the difference between the rental costs in the location where an eligible CAF member serves and a percentage of that member’s gross monthly salary. According to DND, the goal is to ensure that eligible CAF members do not spend more than 25% of their gross monthly salary on purchasing or renting a house in the location where they are serving. See DND, Canadian Forces Housing Differential Frequently Asked Questions.

[12] For more information about the Provisional Post-Living Differential, see DND, Provisional Post-Living Differential Frequently Asked Questions.

[13] In its June 2022 report, NDDN made the following recommendation relating to the Post-Living Differential (PLD): “That the Government of Canada immediately adjust the [PLD] to reflect current economic conditions, including in relation to housing costs.” The recommendation also urged the federal government to “review the [PLD] on an ongoing basis to ensure that Canadian Armed Forces personnel do not experience adverse financial consequences arising from postings.” See NDDN, Modernizing Recruitment and Retention in the Canadian Armed Forces, June 2022.

[14] According to DND, the amount of the CFHD decreases as the pay level of eligible CAF members rises from pay level 1 to pay level 20. For more information, see DND, “Canadian Forces Housing Differential Amounts – How do I find my pay level?,” Canadian Forces Housing Differential (Effective 1 July 2023).

[15] For more information, see DND, Relocation Directive - Chapter 8 Sale and Purchase of Principal Residence.

[16] As NDDN noted in its November 2023 report entitled Canadian Armed Forces Health Care and Transition Services, the Canadian Forces Health Services Group provides health care services to CAF members; CAF family members access such services through provincial and territorial health care systems.

[17] See Office of the National Defence and Canadian Forces Ombudsman, On the Homefront: Assessing the Well-being of Canada's Military Families in the New Millennium, November 2013.

[18] Previously, “BGRS” was “Brookfield Global Relocation Services”; in 2019, Brookfield Business Partners was sold to Relo Group, Inc. In 2022, SIRVA Worldwide, Inc. announced its merger with BGRS to become SIRVA BGRS Worldwide, Inc. See Brookfield Business Partners, Brookfield Business Partners Completes Sale of BGRS, News release, 27 June 2019; SIRVA Worldwide, Inc., About us; and SIRVA Worldwide, Inc., SIRVA and BGRS complete merger to become SIRVA BGRS Worldwide, Inc., News release, 1 August 2022.