PACP Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Public Accounts of Canada 2022

Introduction

The Public Accounts of Canada

The Public Accounts of Canada are presented in three volumes:

- Volume I presents the audited consolidated financial statements of the government, as well as additional financial information;

- Volume II presents the financial operations of the government, segregated by ministry; and

- Volume III presents additional information and analyses.[1]

The Public Accounts of Canada 2022, which pertain to the 2021–2022 fiscal year, were tabled in the House of Commons on 27 October 2022.

The federal government is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of its consolidated financial statements in accordance with Canadian public sector accounting standards.[2] To meet its accounting and reporting responsibilities, “the government maintains systems of financial management and internal control which give due consideration to costs, benefits and risks. These systems are designed to provide reasonable assurance that transactions are properly authorized by Parliament, are executed in accordance with prescribed regulations,” and are recorded properly.[3]

The Auditor General Of Canada’s Responsibility

Per section 6 of the Auditor General Act, the Auditor General of Canada (AG) is responsible for expressing an opinion on the Government’s consolidated financial statements, based on his or her audit conducted in accordance with Canadian generally accepted auditing standards.[4]

Specifically, the AG’s objective is “to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the consolidated financial statements as a whole are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error, and to issue an auditor’s report” including an opinion thereon.[5] To do so, the AG follows the guidelines of the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants “and reviews the financial statements with a materiality of 0.5%; […] (Materiality is the term used to describe the significance of financial statement information to decision-makers.).”[6]

Regarding the Public Accounts of Canada 2022, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG) provided the Government of Canada with an unmodified audit opinion on its consolidated financial statements for the 24th consecutive year. This opinion is an important contribution to the ability of Canada to meet its commitments under the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In particular, the opinion helps Canada meet Sustainable Development Goal 16.6: “Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels.”[7]

On 18 and 22 November 2022, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts (the Committee) held hearings on the Public Accounts of Canada 2022 with the following in attendance:[8]

OAG—Karen Hogan, AG; Etienne Matte, Principal; and Chantale Perreault, Principal

Treasury Board Secretariat of Canada, Office of The Comptroller General of Canada—Roch Huppé, Comptroller General of Canada; Monia Lahaie, Assistant Comptroller General, Financial Management Sector; and Diane Peressini, Executive Director, Government Accounting Policy and Reporting

Finance Canada—Michael Sabia, Deputy Minister; Nicholas Leswick, Associate Deputy Minister; and Evelyn Dancey, Assistant Deputy Minister, Fiscal Policy Branch[9]

The Public Accounts of Canada 2022

The Public Accounts of Canada 2022 outline the government’s financial performance during the 2021–2022 fiscal year and its financial position as at 31 March 2022. Note 3(d) to the Consolidated Financial Statements of the Government of Canada explains the following:

The budget amounts included in the Consolidated Statement of Operations and Accumulated Deficit and the Consolidated Statement of Change in Net Debt are derived from the amounts that were budgeted for 2022 in the April 2021 Budget Plan (Budget 2021). To enhance comparability with actual 2022 results, Budget 2021 amounts have been reclassified to conform to the current year's presentation in the consolidated financial statements, with no overall impact on the budgeted 2022 annual deficit.

Since actual opening balances of the accumulated deficit and net debt were not available at the time of preparation of Budget 2021, the corresponding amounts in the budget column have been adjusted to the actual closing balances of the previous year.[10]

Financial Highlights

Table 1 presents the consolidated figures for the 2021–2022 and 2020–2021 fiscal years and projected figures for 2021–2022 in the 2022 Budget.

Table 1—Consolidated Statement of Operations for the Fiscal Year Ending 31 March 2022 ($ millions)

2022 Budget |

2022 Actual |

2021 Actual |

|

Personal income tax |

180,353 |

198,385 |

174,755 |

Corporate income tax |

50,257 |

78,815 |

54,112 |

Non-resident income tax |

9,887 |

10,789 |

8,107 |

Total income tax revenues |

240,497 |

287,989 |

236,974 |

Other taxes and duties |

57,308 |

62,680 |

46,954 |

Total tax revenues |

297,805 |

350,669 |

283,928 |

Employment insurance premiums |

23,657 |

23,856 |

22,392 |

Proceeds from the pollution pricing framework |

6,352 |

6,341 |

4,380 |

Enterprise Crown corporations and other government business enterprises |

7,109 |

12,804 |

(10,542) |

Net foreign exchange revenues |

1,726 |

873 |

2,173 |

Other |

18,480 |

18,734 |

14,115 |

Total other revenues |

27,315 |

32,411 |

5,746 |

Total revenues |

355,129 |

413,277 |

316,446 |

Old age security benefits, guaranteed income supplement and spouse's allowance |

62,474 |

60,774 |

58,529 |

Major transfer payments to other levels of government |

90,500 |

88,386 |

106,653 |

Employment insurance and support measures |

41,179 |

38,923 |

58,356 |

Children's benefits |

27,190 |

26,226 |

27,370 |

COVID-19 income support for workers |

13,918 |

15,582 |

55,832 |

Canada emergency wage subsidy |

25,955 |

22,291 |

80,166 |

Proceeds from the pollution pricing framework returned |

6,924 |

3,814 |

4,566 |

Other transfer payments |

84,960 |

88,478 |

97,961 |

Total transfer payments |

353,100 |

344,474 |

489,433 |

Other expenses, excluding net actuarial losses |

122,465 |

124,342 |

119,089 |

Total program expenses, excluding net actuarial losses |

475,565 |

468,816 |

608,522 |

Public debt charges |

22,066 |

24,487 |

20,358 |

Total expenses, excluding net actuarial losses |

497,631 |

493,303 |

628,880 |

Annual deficit before net actuarial losses |

(142,502) |

(80,026) |

(312,434) |

Net actuarial losses |

(12,210) |

(10,186) |

(15,295) |

Annual deficit |

(154,712) |

(90,212) |

(327,729) |

Accumulated deficit at beginning of year |

(1,048,746) |

(1,048,746) |

(721,360) |

Other comprehensive income |

N.A. |

4,465 |

343 |

Accumulated deficit at end of year |

(1,203,458) |

(1,134,493) |

(1,048,746) |

Source: Public Services and Procurement Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2022, Volume I, Section 1—Financial statements discussion and analysis, Consolidated Statement of Operations and Accumulated Deficit for the year ended March 31, 2022.

Additional selected financial highlights include the following:

- The government posted a budgetary deficit of $90.2 billion for the fiscal year ended 31 March 2022, compared to a deficit of $327.7 billion in the previous fiscal year.

- The budgetary deficit before net actuarial losses stood at $80.0 billion in 2022, compared to $312.4 billion in 2021. The budgetary balance before net actuarial losses is intended to supplement the traditional budgetary balance and improve the transparency of the government's financial reporting by isolating the impact of the recognition of net actuarial losses arising from the government's public sector pensions and other employee and veteran future benefits.

- Compared to projections in Budget 2022, the annual deficit was $23.6 billion lower than the $113.8-billion deficit projected, mainly reflecting higher-than-expected tax revenues and lower-than-expected expenses for COVID-19 programs. The annual deficit before net actuarial losses was $23.4 billion lower than projected.

- Revenues increased by $96.8 billion, or 30.6%, from 2021, reflecting increases compared to the previous year when COVID-19 lockdowns and federal measures, such as the one-time Goods and Services Tax (GST) credit, resulted in lower revenues.

- Program expenses excluding net actuarial losses decreased by $139.7 billion, or 23.0%, from 2021, largely reflecting lower transfers to individuals, businesses, and other levels of government under the Economic Response Plan.

- Net actuarial losses, which reflect changes in the value of the government's obligations and assets for public sector pensions and other employee and veteran future benefits recorded in previous fiscal years, decreased $5.1 billion, or 33.4%. This decrease primarily reflects the amortization in 2022 of a decrease in the government's obligations for pensions and other employee future benefits based on actuarial valuations prepared for the Public Accounts of Canada 2021.

- Public debt charges were up $4.1 billion, or 20.3%, from 2021, due to Consumer Price Index adjustments on Real Return Bonds, higher interest on the government's pension and other employee future benefit obligations, and an increased stock of interest-bearing debt.

Deficit/Debt-to-Gross Domestic Product

- The accumulated deficit (the difference between total liabilities and total assets), or federal debt, stood at $1,134.5 billion at 31 March 2022. The accumulated deficit-to-GDP (gross domestic product) ratio was 45.5%, down from 47.5% in the previous year.

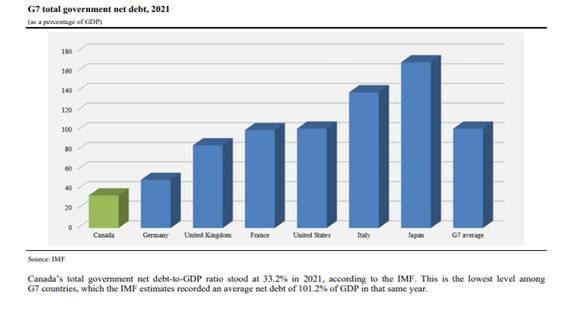

- As reported by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Canada's total government net debt-to-GDP ratio, which includes the net debt of the federal, provincial/territorial and local governments, as well as the net assets held in the Canada Pension Plan and Quebec Pension Plan (CPP/QPP), stood at 33.2% in 2021. This is the lowest level among Group of Seven (G7) countries, which the IMF expects recorded an average net debt of 101.2% of GDP for the same year.[11]

Composition of Revenues and Expenses

For the 2021–2022 fiscal year, the largest share of federal revenues came from personal income tax (48%); corporate income tax (19.1%); and the GST (11.2%). The largest share of expenses over the same period came from major transfers to persons, excluding COVID-19 income support to workers—i.e., elderly benefits, children’s benefits, employment insurance (EI) benefits (25%); other expenses—i.e., the operating expenses of the government’s 131 departments, agencies, consolidated Crown corporations, and other entities (24.7%); major transfers to other levels of government (17.6%); and other transfer payments (17.6%). The Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy and other COVID-19 income support for workers comprised 4.4% and 3.1% of expenses, respectively.

Figures 1 and 2 provide breakdowns of federal government revenues and expenses, respectively, by various categories as reported in the Public Accounts of Canada 2022.

Figure 1—Composition of Revenues for 2021–2022

Source: Public Services and Procurement Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2022, Volume I, Section 1—Financial statements discussion and analysis, Composition of Revenues and Expenses (respectively) for 2022.

Figure 2—Composition of Expenses for 2021–2022

Source: Public Services and Procurement Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2022, Volume I, Section 1—Financial statements discussion and analysis, Composition of Revenues and Expenses (respectively) for 2022.

Figure 3 provides a historical summary of the federal budget balance (the difference between the government's revenues and total expenses over a fiscal year) as a percentage of GDP for the years 1984 to 2022.[12] The blue bars represent the annual surplus or deficit. The black line and boxes represent the annual surplus or deficit before net actuarial losses. By excluding the impact of changes in the value of obligations and assets for public sector pensions, other employee benefits, and future veteran benefits recorded in previous fiscal years, the annual surplus or deficit before net actuarial loss focusses more directly on the results of government operations during the current fiscal year.

Figure 3—Federal Budget Balance as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product, 1984 to 2022

Note 1: In 2018, the government implemented (on a retroactive basis) a change in its methodology for the determination of the discount rate for unfunded pension benefits. Fiscal results for 2009 to 2017 were restated to reflect this change, however restated data for years prior to 2009 is not available.

Source: Public Services and Procurement Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2022, Volume I, Section 1—Financial statements discussion and analysis, Annual surplus/deficit.

The Office of the Auditor General’s Commentary

For the past seven years, the OAG has published a document separate from, but tabled at the same time as, the public accounts entitled “Commentary on the Financial Audits.” In addition to the two usual sections entitled “Results of our 2021–2022 financial audits” and “The Auditor General’s Observations on the Government of Canada’s 2021–2022 consolidated financial statements,” the Commentary on the 2021–2022 Financial Audits begins with a section entitled “Financial Effects of Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response.”

Financial Effects of The Covid-19 Economic Response

The government spent $54.0 billion on direct support measures for individuals and businesses in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021–2022, compared with $212.2 billion in 2020–2021.[13] It also spent $14.5 billion on COVID-19 measures to protect health and safety in 2021–2022, compared with $31.4 billion in 2020–2021.[14]

The OAG found that, in all material respects, the government properly accounted for COVID-19 measures in its 2021–2022 consolidated financial statements. In addition, the OAG’s report on the government’s consolidated financial statements included an emphasis of matter paragraph. This was done “to draw attention to certain amounts in, and notes to, the consolidated financial statements that described the effects of the COVID‑19 pandemic on the Government of Canada, which were significant.”[15] However, that paragraph does not modify the OAG’s audit opinion.

The government has disclosed the overpayments it determined in the notes to its 2021–2022 consolidated financial statements. It also indicated that the amounts of overpayments determined in future years could be significant. Once the government determines it has made an overpayment or a payment to an ineligible recipient, in most cases, it records accounts receivable. The government recorded accounts receivable of $3.7 billion as at 31 March 2021, and this balance rose to $5.1 billion as at 31 March 2022.[16] During one of the hearings, Roch Huppé, Comptroller General of Canada, explained that “this number is obviously not the final number […]; it will be higher than $5.1 billion.”[17]

In the 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 fiscal years, the total unmatured debt rose $459 billion, from approximately $784 billion to $1.243 trillion, and of this, $1.233 trillion was market debt. The maturity dates of this debt ranged from less than 2 years (43%) to more than 20 years (11%). When the term of a marketable bond or a treasury bill comes to maturity, the government may issue new debt to raise funds to pay the maturing debt. This new debt is issued at current market rates, which have recently been increasing. In its Budget 2022, the government projected that overall public debt charges will rise to $42.9 billion, making up 8.5% of the government’s projected expenses, by the 2026–2027 fiscal year, compared with 4.9% in the 2021–2022 fiscal year.[18]

During a hearing, Nicholas Leswick, Finance Canada, referred to the Fall Economic Statement 2022, which stated that public debt charges would represent 1.3% of GDP in 2027–2028, compared with 1.0% in 2021–2022. He also referred to Budget 2022, which contains a sensitivity analysis. According to this analysis, a 100-basis-point increase in all interest rates would increase public debt charges by $9.3 billion in 5 years, which would partly be offset by $2.4 billion in increased revenues.[19]

Results of the 2021–2022 Financial Audits

The OAG stated that it was satisfied with the “timeliness and credibility of the financial statements prepared by 68 out of the 69 government organizations”[20] that it had audited, but it noted that “the audited financial statements of the Reserve Force Pension Plan have not been issued on a timely basis.”[21] It expects to complete the audits of the Reserve Force Pension Plan’s 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 financial statements by January 2023. After that, it expects the financial statements to be prepared on a timely basis (i.e., at the same time as the public accounts).

Related to the Trans Mountain Corporation, the OAG noted that in “its 31 December 2021 financial statements, the corporation disclosed a significant uncertainty of whether it could continue its operations because of the government’s announcement with respect to funding. [The OAG’s] audit opinion on the Trans Mountain Corporation’s 31 December 2021 financial statements also drew attention to this uncertainty.”[22] It added that the “corporation’s unaudited financial statements for the first quarter of 2022 reported there was no longer uncertainty over continuing operations. [The OAG] will examine and report on this in our audit of the corporation’s 31 December 2022 financial statements.”[23]

Michael Sabia, Deputy Minister, Finance Canada, explained the following regarding the government’s participation in Trans Mountain:

We considered the cash flow associated with that asset and have done a tremendous amount of analysis on the issue prior to providing the company with a $10 billion loan guarantee. We are quite confident that this corporation will be able to manage such a debt very well, and our department does not believe that this guarantee represents a significant financial risk. We are very comfortable with that…

[The] construction process is moving along fairly well. The government intends to eventually sell this asset. When the construction of this huge, complex and difficult project is complete, I think the time will come to sell this asset, since the government does not necessarily need to own a pipeline of this kind.[24]

Observations of the Auditor General of Canada

Pay Administration

Since 2016, weaknesses in internal control of the HR-to-pay process prevented the OAG from testing and relying on those controls in its audit work. The OAG expects “that the government will return to having pay processes with internal controls that ensure employees are paid accurately and on time. This expectation remains regardless of whether the government keeps its current pay system for some organizations or implements a new one.”[25]

Roch Huppé explained what should be expected of the pay system:

[Public Services and Procurement Canada] handles about 100,000 to 120,000 pay requests on a monthly basis. The objective is to treat all of these requests, 95% of the time, within an acceptable time frame. You're never going to have no backlog, obviously, as the Auditor General mentioned a little earlier. One could see that something in the neighbourhood of rolling 5%, or around there, would probably seem reasonable.[26]

In its audit work, the OAG “found that

- 28% of employees … sampled had an error in their basic or acting pay during the 2021–22 fiscal year, compared with 47% in the prior year

- 17% of employees … sampled still required corrections to their pay as at 31 March 2022, a decrease from the 41% reported in the prior year.”[27]

According to the OAG, in “addition to strengthening internal controls and addressing outstanding pay action requests, the government needs to take steps to recover overpayments of salaries, wages, or employment-related allowances. It should proceed in a timely manner because legal limitation periods mean that certain recovery mechanisms may no longer be available to the government in its recovery efforts.”[28]

Roch Huppé added the following on the improvements to the pay system:

Two things are happening. There's a lot of work being done on Phoenix. We're trying to stabilize it as much as possible, and over the years there have been system modifications and investments in that system. At the same time, as you would have seen in the media and so on, we're also in the midst of testing another potential system.

We are taking our time. We don't want to make the same mistakes, so the testing is very complex scenarios with departments.[29]

National Defence Inventory and Asset Pooled Items

According to the OAG, in “2016, National Defence established a 10-year inventory management action plan to better record, value, and manage the department’s inventory. While it has completed most of its commitments, one important remaining commitment—namely, implementing a modern scanning and barcoding capability in the inventory management system—is delayed. The original schedule has been delayed because the department is taking more time to clearly define its requirements. It is important that this modernized capability be implemented, given the potential benefits it will bring to the management and accounting of inventory.”[30]

Karen Hogan, Auditor General of Canada, added the following explanation about the nature of the inventory problem:

Sometimes it's not that National Defence employees don't know that they don't have it; it's that they can't tell you exactly the location. There are a lot of inventory items that move around. There are items on bases. There are items in big depots. The controls at all of those locations might be different, so managing inventory country-wide is a process that they need to get a handle on.

When we tested, we continued to find errors. I think it was about 15% of the items that we counted continued to have errors. It's an improvement from last year, but it is still a large error rate.[31]

Additional Insights

Environmental, Social and Governance Reporting

In Canada, accounting standards do not currently require organizations to report on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors or on sustainability. Even without requirements in accounting standards, federal organizations are increasingly making disclosures on ESG matters because of requirements in federal legislation or in government policies to achieve intended outcomes. Recent government commitments indicate that additional ESG reporting will soon be required or expected. The OAG is following developments and will engage with the audited federal organizations to understand and review any new disclosure requirements.[32]

On this topic, Roch Huppé provided the following at the first hearing:

Obviously, there is some reporting that is happening right now. If you think about environmental types of reporting, we have the greening government strategy and others. That said, there's a lot of work now that's going to get done on imposing, potentially, other standards that will come and affect what we report and how we report on this… Be reassured that we are following this. Obviously, as soon as more information and standards get developed and imposed, we will adapt our reporting accordingly.[33]

At the second hearing, he added the following on reporting climate-change related damages:

First of all, let me say that I definitely agree with the importance of having more granular-level data around that type of reporting. I come back to the fact that standards are being developed. That said, even without the standards, we always strive to provide the best information possible from a financial reporting perspective.

As I said, we do have some reporting on our climate objectives and so on through the greening government strategy, for example, on the site of the Treasury Board Secretariat. Other departments also have that.[34]

Therefore, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 1—Regarding Environmental, Social, and Governance criteria

That, by 31 January 2024, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat provide the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a report explaining the measures taken to improve accounting practices requiring federal organizations to present detailed reports about their environmental, social, and governance as well as sustainable development criteria.

Asset Retirement Obligations

Starting in 2022–2023, a new accounting standard will establish how to account for asset retirement obligations. These represent costs associated with legal requirements to take actions to remediate or dispose of some tangible capital assets. According to the OAG, the government has a great deal of work to do in its preparation for this new standard.[35]

Observations

The following is a selection of the topics raised at the hearings.

Canada’s Net Debt-to-GDP Ratio and the Canada/Quebec Pension Plans

Regarding the international comparison of Canada’s net debt-to-GDP ratio in the Public Accounts of Canada 2022, this specific calculation does not include actuarial assessments of future CPP/QPP payment obligations, nor future statutory employee and employer contributions to both schemes; i.e., it does not include the amounts it may have to pay out or the amounts it could collect.

In response to questions about Canada’s net debt-to-GDP ratio, Karen Hogan explained that the IMF calculation is one that levels Canada to other countries and allows one to compare it to other countries. She added that, conversely, there is the straight debt-to-GDP ratio, or equity ratio, that one would normally look at when analyzing financial statements; both metrics tell a slightly different story.[36]

Nicholas Leswick elaborated on what the different ratios represent:

[The straight debt-to-GDP ratio] is a good reflection of a country's ability to repay its debt, to service its debt in relation to the size of its economy, so full stop on that. I think there is consensus that it's a good metric in terms of overall debt sustainability over the near term, and over the longer term from a fiscal sustainability perspective.

I acknowledge that there are some pitfalls and caveats when you start comparing between countries—I think we've touched on that at this committee before—because every country is different. You have the highest sovereign level of governments and you have provinces at sub-sovereign levels. For the IMF to establish this level of comparability, they have to do a lot of different puts and takes.

We do this reconciliation on page 35 [of Volume I] to be very clear and transparent in terms of how we go from a federal debt-to-GDP ratio, which is the kind of target the government talks to in terms of how it wants to achieve a certain target in its budgets or updates, versus Canada's net debt-to-GDP ratio, which is what is compared across countries. That reconciliation is shown on page 36.[37]

Figure 4—Comparison of Net Debt to GDP for the Group of Seven Countries

Source: Public Services and Procurement Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2022, Volume I, Section 1—Financial statements discussion and analysis, International comparisons of net debt, p. 35.

In response to questions about how rising interest rates might affect this ratio, and the difference between Canada’s relative performance versus its actual debt levels, Nicholas Leswick provided the following:

As the interest rate goes higher, we pay more interest on our debt that we turn over. What the impact on the ratio itself would be depends at what pace the economy is growing. We expect the public debt charges-to-GDP ratio to tick up slightly because of the higher interest rate environment.

You hear the expression the “cleanest dirty shirt” in the world of debt-to-GDP ratios, because nobody likes public debt. But yes, you're right. We publish these in our budgets and fall updates in terms of Canada's G7 and G20 comparison around these types of debt metrics.[38]

In response to a question about how Canada would compare to its peers if the CPP and QPP assets were removed, Nicholas Leswick responded as follows:

To be clear, this math, this methodology and this calculation are entirely an IMF calculation. This is what the IMF does to put all these countries on a comparable basis. That's because the reality is that a lot of G7 countries—this is actually quite shocking—take their social security contributions, like CPP premiums, and put them against general revenues. They don't have dedicated asset accounts.

It's a recognition that we don't take the premiums into general revenues. Again, I feel like I'm defending an IMF position—which I've pretty much fought my entire career—in trying to reconcile some of this craziness.

It's the same thing in terms of public sector pension schemes, such as employee pensions benefits for the public sector employees. You'll see a matter of adjustment in the same table on page 36, as well. This is what the IMF does to put all these G7 countries on some sort of level of comparability around their debt-to-GDP metrics.

That's my best explanation, but I principally have the same concerns. It is a showcase. It's their best effort at what the IMF can do in terms of apples to apples comparison.[39]

Lastly, when asked about how Canada debt-to-GDP ratio ranks against peer economies, Michael Sabia provided the following:

This issue about debt-to-GDP and deficit-to-GDP, these are ultimately relative issues about how we stack up against other countries in the world because really that's what's relevant here. It's not an absolute issue. It's a relative issue.

In both debt-to-GDP and deficit-to-GDP, within the G7 we are number one. We are in the strongest fiscal position of any country in the G7.[40]

It should also be noted that in response to a question about the sustainability of the CPP, Michael Sabia provided the following:

I think the Canada pension plan is extremely solid, for a couple of reasons.

I think there are two sides to this: first, how, from a government and government policy point of view, both benefits and premiums are always on the radar screen and are judged very carefully; and, second—and I'd like [to] put particular emphasis on this…It is an exceptionally well-managed fund.

Having spent 11 years of my life in the fund management business in another fund—not [Canada Pension Plan Investment Board]—I can say for that fund in particular, among all the Canadian pension funds—and they're all very good, and highly respected globally—the Canada pension plan and the investment board that manages the Canada pension plan I think are among the best in the world.

I think Canadians should feel extremely good about the quality of Canada's pension system. There's the CPP, the Canada pension plan itself…but then there are all the other elements of the infrastructure of pensions within Canada: old age security, the guaranteed income supplement, etc.

One of the strengths of public policy in Canada is the security of the social safety net for an aging population, which I think helps set the country apart on a global basis. I think it's very good.[41]

Doubtful Accounts, Write-Offs, Waivers, Etc.

When asked to explain to the committee the difference between write-offs, forgiveness, remissions and waivers, Roch Huppé responded as follows:

A [write-off] is basically a situation in which you have active collection and you've reached a point at which, for different reasons.... I have the Auditor General looking at me here. We have set criteria in what we call our debt [write-off] regulations, under which, if you cannot locate the debtor or there are bankruptcy issues, you can do a [write-off]. That does not extinguish the debt. It means that if the conditions change, then the collection can be restarted. We write them off and we provide a clear picture in our books of what we deem to be collectable.

When you get into the zone of forgiveness and remissions, the difference is that you extinguish the debt. That means you're no longer able to legally collect any of that debt. That could be in an area in which there's an unfair situation happening or there could be compassionate reasons… The idea is not that you've exhausted all of your collection, but really that you're making a decision to completely extinguish the debt for—as I said—other reasons.[42]

He also added the following for clarity:

When I say you write something off, like I said, you need to meet certain criteria. Your collection action will basically stop. I'll give you an example.

On the tax write-offs—which are a few billion every year—the CRA will receive money from individuals who, although their account has been written off, will [still] pay their amount due. There are monies that are still recovered, but not necessarily through active collection action a lot of the time.

However, if you're in a situation in which you cannot locate a debtor and then you have information that may allow you to resume collection action, you're entitled to do that in some of these cases.[43]

Additionally, when asked to explain the reasons for which write-offs and forgiveness increased by 75% from the previous fiscal year, he responded with the following:

It was mainly due to tax receivables and the work the Canada Revenue Agency is doing. During the pandemic, I would say there was a certain amount of relief, but more flexibility was provided to the taxpayers in times of crisis.

Somewhere in 2021, the more traditional collection actions slowly went back to normal. That's why we're seeing a bit of a spike this year compared to previous years. It's because there was a bit of an adjustment in the collection measures that were being done.[44]

The Committee makes the following recommendation:

Recommendation 2

That the Government of Canada, in accordance with all applicable laws, disclose in the Public Accounts the names of any corporations that receive loan forgiveness from the government and crown corporations and provide the value of loan forgiveness received in each case.

It should be noted that although there were discussions about allowances for unrecoverable COVID-19 support payments, the Committee plans to address these issues in further detail in possible future studies pertaining to the OAG’s audits of Specific COVID-19 Benefits.

Passport Canada

When asked about why there were large variances between the funds allocated to Passport Canada in the 2021 and 2022 estimates and the actual funding amounts as presented in the Public Accounts of Canada, Roch Huppé responded as follows:

The difference between the estimate and the actual is basically simply what their expectation was of the business being taken up. As I said, there was a difference of one million passports between 2021 and 2022. They expected the business in 2022 to be even higher than that and perhaps to be even at prepandemic levels, which was not the case. It fell in the middle, I would say.[45]

He also explained that there was a settlement of some of the collective agreements for the Public Service Alliance of Canada and the retroactive pay for those settlements happened in the 2020–2021 fiscal year. Also linked to those negotiations were some Phoenix damages; those one-time payments were done within 2021. Moreover, there was a moratorium on the automatic cashing-out of annual leave.[46]

Conversely, the increase in revenues was as a result of the return of international travel: a million more passports issued in 2021–2022 than in the previous year.[47]

Past Recommendations from The Public Accounts Committee

During the hearings on the Public Accounts of Canada 2022, discussions were held regarding past recommendations of the Committee.

Public Accounts of Canada 2020

In its report on the Public Accounts of Canada 2020, the Committee had made the following recommendation:

Recommendation 1

That the Office of the Comptroller General, at the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, in consultation with the Office of the Auditor General of Canada, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts and interested parties, study potential changes to the Public Accounts of Canada to make them more user-friendly and accessible while ensuring a high degree of transparency and accountability from the Government of Canada.

Roch Huppé provided the following information regarding the implementation of that recommendation:

Based on the recommendations of this committee, the government committed to study potential improvements, and I am pleased to report that this work is under way. To identify possible streamlining opportunities, we reviewed the existing content of the public accounts to identify information that is available through other means not required by legislation, and some with thresholds that have not changed for decades.

In addition, we have received feedback from the Library of Parliament on opportunities to improve the presentation and format of the Public Accounts of Canada. At the same time, we have engaged key stakeholders on additional potential improvements through a survey...

I would like to reiterate that any proposed changes will be carefully examined to ensure that the government's financial information continues to support transparency and accountability to parliamentarians and Canadians.[48]

Public Accounts of Canada 2021

In its report on the Public Accounts of Canada 2021, the Committee had made the following recommendation:

Recommendation 2

That the Government of Canada amend the Financial Administration Act to change the deadline for the tabling of the Public Accounts of Canada from December 31st to October 15th, to align with the tabling date of some Canadian provinces and peers in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

On that issue, Karen Hogan provided the following:

With regard to advancing the publication timelines for the public accounts, … I guess the statement I would make is that it needs to be a joint effort between both the auditors and the financial statement preparers, so we both become more efficient and effective. It means that deadlines all across the government need to move up, or that efficiencies need to be found in publications.[49]

Roch Huppé added the following explanation:

We obviously have to produce the e-document that is e-tabled. We have to produce what we call an html. Really, that is the five weeks it takes right now to make every table, and we have close to 2,000 tables that are fully accessible.

We've already started to work with some key stakeholders to try to find efficiencies within that five-week period. That will be helpful in enabling us to bring that date back.... However, sadly, right now those are the time limits.[50]

The Committee had also made the following recommendation in that report:

Recommendation 3

That the Government of Canada consider requiring Crown corporations to divulge all expenditures in the same manner as federal departments and agencies in Volume III of the Public Accounts of Canada; consult with interested stakeholders on the ways this could be achieved, the advantages it would provide and the potential additional administrative burden this could cause; and that it provide the Committee with a report comprising of a comprehensive analysis of this matter, no later than 30 April 2023.

On the financial reporting and transparency of Crown corporations, Nicholas Leswick provided the following:

These Crown financial organizations are massive federal enterprises that have a lot of capital and a lot of spending power, but they are distinct beasts. They live in different corners of the Financial Administration Act, and they have different powers and authorities in governance structures.

However, I totally understand the point here. I don't know that we consolidate them or integrate them line for line in our public accounts, but whether their annual reporting and corporate planning processes aren't really meeting the needs of parliamentarians.... We don't have a good understanding of what they're spending or how they're deploying capital, which is 100% taxpayer money. I absolutely take that point.[51]

Conclusion

The Committee recognizes the Government of Canada for maintaining the integrity of its financial controls and reporting, which resulted in a twenty-fourth consecutive unmodified audit opinion from the Auditor General of Canada.

In this report, the Committee makes two recommendations, and strongly encourages the government to work diligently to find ways to rectify the persistent problems associated with the Phoenix pay system, and to correct any overpayments and underpayments made to recipients of benefits for individuals and employers made during the COVID-19 pandemic.

[1] Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC), Public Accounts of Canada 2022.

[2] Ibid.,Volume I, Section 2 – Consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada and report of the Auditor General of Canada, Statement of responsibility.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., Auditor General of Canada – Independent Auditor’s Report. For additional information, refer to the Auditor General Act.

[5] Ibid.

[6] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Government Decisions Limited Parliament’s Control of Public Spending of the 2006 Report of the Auditor General of Canada, 1st Session, 39th Parliament, October 2006.

[7] Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG), Commentary on the 2021–2022 Financial Audits, paras. 23–24.

[8] Note that on 15 November 2022, the Committee held a preliminary in-camera hearing on the Public Accounts 2022 to develop further its knowledge of this topic with representatives from the Canadian Audit & Accountability Foundation, a non-for-profit organization dedicated to promoting and strengthening public sector performance audit, oversight, and accountability.

[9] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, 18 November 2022 (Meeting No. 38) and 22 November 2022 (Meeting No. 39).

[10] PSPC, Public Accounts of Canada 2022, Volume I, Section 2, Notes to the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada, Note 3 (d).

[11] PSPC, Public Accounts of Canada 2022, Volume I, Section 1 – Financial statements discussion and analysis, 2022 financial highlights.

[12] Ibid., Budgetary Balance.

[13] OAG, Commentary on the 2021–2022 Financial Audits, Exhibit 1.

[14] Ibid., Exhibit 2.

[15] Ibid., para. 10, and PSPC, Public Accounts of Canada 2022, Volume, Section 2 – Consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada and report of the Auditor General of Canada, Independent Auditor’s Report, Emphasis of Matter – Impact of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

[16] OAG, Commentary on the 2021–2022 Financial Audits, paras. 12–13.

[17] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, 18 November 2022, Meeting No. 38, 1315.

[18] OAG, Commentary on the 2021–2022 Financial Audits, paras. 20 and 21.

[19] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, 18 November 2022, Meeting No. 38, 1445; Finance Canada, Fall Economic Statement 2022, p. 51; and Finance Canada, A Plan to Grow Our Economy and Make Life More Affordable, Budget 2022, pp. 247–248.

[20] OAG, Commentary on the 2021–2022 Financial Audits, para. 25.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid., para. 28.

[23] Ibid., para. 30.

[24] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, 22 November 2022, Meeting No. 39, 1705.

[25] OAG, Commentary on the 2021–2022 Financial Audits, paras. 31–32.

[26] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, 18 November 2022, Meeting No. 38, 1420.

[27] OAG, Commentary on the 2021–2022 Financial Audits, para. 33.

[28] Ibid., para. 37.

[29] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, 22 November 2022, Meeting No. 39, 1700.

[30] OAG, Commentary on the 2021–2022 Financial Audits, para. 42.

[31] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, 18 November 2022, Meeting No. 38, 1340.

[32] OAG, Commentary on the 2021–2022 Financial Audits, paras. 45, 46 and 48.

[33] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, 18 November 2022, Meeting No. 38, 1355.

[34] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, 22 November 2022, Meeting No. 39, 1625.

[35] OAG, Commentary on the 2021–2022 Financial Audits, p. 19–21.

[36] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, 18 November 2022, Meeting No. 38, 1315.

[37] Ibid., 1405.

[38] Ibid., 1425.

[39] Ibid., 1435.

[40] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, 22 November 2022, Meeting No. 39, 1720.

[41] Ibid., 1630.

[42] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, 18 November 2022, Meeting No. 38, 1435.

[43] Ibid., 1440.

[44] Ibid.

[45] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, 22 November 2022, Meeting No. 39, 1555.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid.

[48] House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, 18 November 2022, Meeting No. 38, 1205.

[49] Ibid., 1310.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Ibid., 1350.