OGGO Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

REACHING CANADIANS WITH EFFECTIVE GOVERNMENT ADVERTISING

IntroductionOn 1 June 2017, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates (the Committee) adopted a motion to undertake a study of the changes to the federal government’s communications policy as it pertains to government advertising, including the consideration of the policy and related procedures and the role of third-party oversight. Between June and October 2017, the Committee held 3 meetings and heard from 14 witnesses, including federal officials from the Privy Council Office (PCO), the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS), and Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC); representatives from Advertising Standards Canada (ASC); academics; and representatives from 4 media associations. The Committee also received two briefs. The full list of witnesses is available in Appendix A and the list of briefs submitted is found in Appendix B. The report of the Committee’s findings contains five chapters:

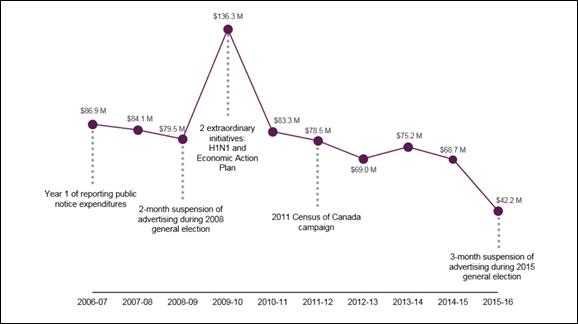

Government advertising may not represent a significant portion of total government spending, but it does receive a lot of attention – for both the messages it shares with citizens and its impact on the Canadian media industry. In 2015–2016, the federal government spent $42.2 million on advertising.[1] In comparison, advertising expenditures averaged around $80 million per year between 2005–2006 and 2014–2015, as noted in testimony before the Committee by Christiane Fox, Deputy Minister of Intergovernmental Affairs and Youth at PCO.[2] Figure 1 presents total advertising expenditures over the 10-year period between 2006–2007 and 2015–2016. As noted in the figure, the decrease for 2015–2016 is attributed in part to the three-month suspension of advertising during the 2015 general election. In addition, between 2010–2011 and 2015–2016, advertising expenditures generally decreased year over year, from $83.3 million in 2010–2011 to $42.4 million in 2015–2016. Figure 1 – Federal Government Advertising Expenditures ($ millions), 2006−2007 to 2015−2016

Source: Figure reproduced from Public Services and Procurement Canada, Annual Report on Government of Canada Advertising Activities, 2015–2016, p.7 (Chart 1: Advertising Expenditures – A Ten Year Perspective). Government advertising is funded through the Central Advertising Fund administered by TBS and through departmental operating budgets. Ms. Fox told the Committee that the government announced a permanent reduction in advertising expenditures of $40 million annually. She commented that, based on the most recent information collected by PSPC, the expenditures for 2016–2017 were expected to be approximately $40 million and she added that between $25 million and $30 million of this amount will be funded though the Central Advertising Fund, with the balance from departmental expenditures. Jonathan Rose, Associate Professor in the Department of Political Studies at Queen’s University, who testified as an individual, agreed that reducing government spending on advertising was a step in the right direction. He noted, however, that the final figures for this most recent fiscal year will not be available until the government publishes its annual report on advertising in January 2018, 10 months after the 2016–2017 fiscal year-end.[3] According to Marc Saint-Pierre, Director General of Government Information Services Sector at PSPC, departments and agencies launched more than 70 campaigns in 2015–2016, and 11 institutions spent more than $500,000 on their campaigns. Table 1 presents federal government advertising expenditures and major campaigns from 2009–2010 to 2015–2016. Table 1 – Federal Government Advertising Expenditures and Major Advertising Campaigns, 2009–2010 to 2015–2016

Note: a. Due to the federal election, there was a mandatory suspension of federal advertising for 94 days. Sources: Table prepared using data obtained from Public Services and Procurement Canada, 2009–2010 Annual Report on Government of Canada Advertising Activities, pp. 17 and 20–22; Annual Report on Government of Canada Advertising Activities 2010–2011, pp. 7 and 10; Annual Report on Government of Canada Advertising Activities 2011–2012, pp. 3 and 8–12; 2012–2013 Annual Report on Government of Canada Advertising Activities, pp. 3 and 8–10; 2013–2014 Annual Report on Government of Canada Advertising Activities, pp. 3 and 7–9; Annual Report on Government of Canada Advertising Activities 2014–2015, pp. 2 and 10–13; and Annual Report on Government of Canada Advertising Activities 2015–2016, pp. 3 and 15–17. The majority of government advertising is placed by the Agency of Record,[4] a private company under contract with PSPC, in the various media channels. In its annual report on government advertising, PSPC presents expenditures for Agency of Record advertising placement. Figure 2 presents Agency of Record advertising expenditures by media type as a percentage of annual totals for 2006–2007, 2010–2011 and 2015–2016. For 2015–2016, the government spent 51% on television, 34% on digital and a total of 15% on print, radio, and out-of-home advertising, according to Mr. Saint-Pierre. The figure shows that government expenditures on most media types have declined in recent years, with the exception of digital media which is increasing significantly, and television advertising which fluctuates with an upward trend. Figure 2 – Agency of Record Advertising Expenditures by Media Type (% of total), 2006−2007, 2010−2011 and 2015−2016

Source: Figure prepared using data from Public Services and Procurement Canada, Advertising annual reports, 2006–2007, 2010–2011, and 2015–2016. Figure 3 presents Agency of Record advertising expenditures for traditional media and digital media as a percentage of annual totals for the 10-year period from 2006–2007 to 2015–2016. Ms. Fox noted that in 2011–2012, the government spent 14% of its advertising expenditures on digital media, as compared to 34% in 2015–2016. Dr. Rose highlighted in a brief submitted to the Committee that “[i]nternet advertising by government has grown 126% from 2012 to 2015–16.” Figure 3 shows that traditional media expenditures have declined with the increase in digital media advertising. Figure 3 – Agency of Record Advertising Expenditures in Traditional Media and Digital Media (% of total), 2006−2007 to 2015−2016

Source: Figure prepared using data from Public Services and Procurement Canada, Advertising annual reports, 2006–2007 to 2015–2016. Figure 4 presents government advertising placed by the Agency of Record in specialized print, radio and television media aimed at official language minority, ethnic, and Aboriginal communities. Figure 4 –Agency of Record Advertising Expenditures in Official-Language Minority, Ethnic and Aboriginal Media (in $ millions), 2006−2007 to 2015−2016

Source: Figure prepared using data from Public Services and Procurement Canada, Advertising annual reports, 2006–2007 to 2015–2016. As Figure 4 shows, with the increasing emphasis on digital media, the government’s placement of advertising in community newspapers and ethnic media has declined. According to Duff Jamison, Chairman of Government Affairs for the Alberta Weekly Newspapers Association, “A decade ago the federal government spent 47% of its ad budget in newspapers: 28% in dailies and 19% in community, ethnic, and aboriginal weeklies. In the 2014–15 fiscal year it spent 7% in total on newspapers: 1% in dailies and 6% in weeklies. In that same period, the spending with Internet companies rose from 6% to 28%.” For the fiscal year 2015–2106, the government spent $3.4 million on polling, in comparison with $12.5 million for 2016–2017, according to Mr. Saint-Pierre. Mr. Saint-Pierre also said that the government spends very little on advertising outside of Canada and that most advertising is published in Canada in media directed to Canadians. In a follow-up response to the Committee, PSPC indicated that the federal government spent $813,841 in 2014–2015, $11,377 in 2015–2016 and $3,318 in 2016–2017 on advertising in other countries. When describing ways that the government can reduce costs, officials referred to the centralized purchasing of media space, as well as the impact of the coordination role. According to Mr. Saint-Pierre, the Agency of Record, which purchases media space on behalf of the federal government, as well as other companies, realizes cost savings for the government because they are able to obtain the best price for media. The requirement for centralized purchasing of media space is outlined in the government’s policy. According to Ms. Fox, this requirement is necessary to ensure that everyone follows the same approach given that government operations are large-scale and in some cases decentralized by the government’s regional presence. She added that planning campaigns over a longer period of time can lead to savings due to the guaranteed funding. TBS and PSPC provided information on the number of full-time equivalent employees and total salaries related to federal government advertising at TBS, PCO and PSPC for the period 2014–2015 to 2017–2018. This information is presented in Table 2. Table 2 – Number of Full-Time Equivalent (FTE) Employees and Total Salaries Related to Government Advertising for the Treasury Board Secretariat, Privy Council Office and Public Services and Procurement Canada, 2014–2015 to 2017–2018

Note: a. These amounts represent the salary range for each position associated with the FTEs. Source: Table prepared using data obtained from Treasury Board Secretariat, Follow-up on the June 15, 2017 meeting of the Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates, pp. 2, 3 and 5 [Correspondence with OGGO, 25 October 2017]. TBS also indicated that internal advertising does not include “the Government of Canada’s own websites and unpaid social media presence.”[5] TBS added that in 2015–2016, the federal government’s information technology (IT) expenditure was $5.3 billion. However, it specified that “[g]iven the multi-purposed uses of IT and related personnel, it is not possible to isolate the Government of Canada’s expenditures on its external websites and social media. Though, generally, these expenditures would represent a very small portion of the Government’s overall spending on IT.”[6] 1.1 Committee ObservationsThe Committee recognizes the government’s new policy and its commitment to reduce partisan advertising. The Committee also recognizes that Canadians look to both traditional and digital media for information and supports the view that Canadian-content media is important for informing Canadians.

2.1 Current Government Policy on Communications and Federal IdentityOn 11 May 2016, the federal government adopted the Policy on Communications and Federal Identity. The policy replaced the 2006 Communications Policy of the Government of Canada and the 1990 Federal Identity Program Policy. It applies to the government departments and agencies in Schedule I of the Financial Administration Act and to the divisions or branches of the federal public administration in Schedule I.1 of the Act. Certain sections of the policy and the requirements of the Directive on the Management of Communications do not apply to the Office of the Auditor General of Canada; the Office of the Chief Electoral Officer; the Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada; the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages; the Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada; the Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada; and the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada. Further, Alex Marland, Professor in the Department of Political Science at Memorial University of Newfoundland, testifying as an individual, commented that there should be a distinction between the different arms of government. For example, he said that Crown corporations, which are acting in a competitive market place, should not necessarily adhere to the same communications and advertising requirements as departments and agencies. The policy has the following four objectives:

Louise Baird, Assistant Secretary with Strategic Communications and Ministerial Affairs at TBS, told the Committee that the new policy replaces a policy that came into effect in 2002 and was updated in 2006. The policy sets out rules not only for the government’s communications activities, but also for the way in which it communicates with Canadians about its policies, programs and services. She also pointed out that the policy established rules concerning the Government of Canada’s corporate identity, which includes the Canada word mark, departmental signatures, and the arms of Canada, and that the Government of Canada’s identity still has primacy over the identity of individual departments and agencies. In a response to a question from a Committee member, Ms. Baird clarified that the policy applies to all government communications including websites. Dr. Marland suggested that Parliament regularly update the federal government communications policy and said that he was pleased to see that the Committee was undertaking this current study. In a response to a question from a Committee member, Dr. Rose articulated that any advertising policy should strive for independence and transparency. 2.1.1 Main Changes to the Previous Policy

Ms. Baird indicated that the new policy includes the following four key changes:

2.2 Directive on the Management of CommunicationsTo support the policy, the federal government released the Directive on the Management of Communications on 11 May 2016. The directive describes the key requirements for heads of communications, as well as the roles and responsibilities of PCO, PSPC, Service Canada, Global Affairs Canada, and Library and Archives Canada. It replaces the following Treasury Board policy instruments: the 2006 Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, the 1990 Federal Identity Program Policy, the 2014 Procedures for the Management of Advertising, the 2014 Procedures for the Management of Public Opinion Research, and the 2013 Standard on Social Media Account Management. Ms. Baird explained that, in order to streamline the government policy, duplicative requirements from other Treasury Board policies were removed from it and as a result, the number of policy requirements regarding government communications has been reduced from 330 to 97. She said that the policy is more precise because it clarifies accountabilities for deputy heads and for heads of communications. She added, moreover, that the new policy gives departments and agencies more flexibility to determine roles and responsibilities based on their specific needs. 2.3 Mandatory Procedures for AdvertisingThe directive contains the Mandatory Procedures for Advertising, which also took effect on 11 May 2016. The procedures describe that the communications branches of government departments and agencies must plan and coordinate, contract, and conduct production and media planning of advertising activities, and pretest and evaluate advertising campaigns costing more than $1 million. Mr. Saint-Pierre informed the Committee that every advertising campaign valued at over $1 million has to be tested in advance and evaluated by an independent company, which is usually a public opinion research company. He added that Library and Archives Canada publishes findings from companies’ reports on its website as required by law and Treasury Board policies. He also explained that the costs related to the evaluation of advertising campaigns valued at over $1 million are included in the total costs of advertising campaigns that departments and agencies incur and that they must forecast from the outset. Dr. Rose expressed the view that all government advertising plans, regardless of their total value, should come with a public opinion survey demonstrating the need for the campaign as it is the case in Ontario. 2.4 Roles of Federal OrganizationsSeveral federal organizations are involved in the planning of government advertising activities. Mr. Saint-Pierre explained that under the policy, a department or an agency cannot develop an advertising campaign from start to finish without consulting and collaborating with PCO, TBS, and PSPC. As well, Global Affairs Canada advises departments and agencies on advertising in foreign markets.[7] 2.4.1 Government Departments and AgenciesGovernment department and agency heads of communications are responsible for preparing their organizations’ advertising proposals by applying the principles of the Canadian Code of Advertising Standards[8] and by complying with the definition of non-partisan communications set out in the policy and the directive.[9] The Code which was first published in 1963 and has since been revised on a regular basis, was established in order to promote advertising. It is administered by ASC and its purpose is “to help set and maintain standards of honesty, truth, accuracy, fairness and propriety in advertising.” It contains the following 14 provisions that advertisers, including the federal government,[10] should adhere to both in letter and in spirit:

Government department and agency communications branches must submit all advertising campaigns with budgets greater than $500,000 for mandatory ASC review[11] and ensure that advertising campaigns that have a total media buy of over $1 million are evaluated using the Advertising Campaign Evaluation Tool issued by the Communications and Consultations Secretariat of PCO. They must also forward campaign performance indicators and research results to the Secretariat.[12] As well, government departments and agencies must ensure that determinations made by ASC are addressed before publishing the advertising.[13] 2.4.2 Cabinet and the Privy Council OfficeCabinet receives all advertising proposals, decides which ones will proceed and determines the maximum funding amount and source of funds, from either existing departmental resources or the Central Advertising Fund.[14] Ms. Fox indicated that PCO has a coordination role in government communications, which allows for the creation of synergies among departments and agencies that often work independently from one another. She also explained that PCO coordinates government communications and, in collaboration with departments and agencies, ministers’ offices, and the Prime Minister’s Office, the annual planning of advertising activities based on government priorities. The plans must be approved by the prime minister and presented to the Cabinet Committee on Open and Transparent Government and Parliament. In order to obtain the required funds for the approved advertising campaigns funded through the Central Advertising Fund, PCO prepares a submission to TBS. Ms. Fox added that “PCO provides leadership, a challenge function, strategic direction and coordination during the implementation of major advertising campaigns.” PCO also reviews draft creative materials, media buy strategies and plans and advises departments and agencies on their pretesting and evaluation plans for advertising campaigns with a total media buy of over $1 million.[15] In addition, PCO manages the Advertising Campaign Evaluation Tool used to evaluate all advertising campaigns that have a total media buy of over $1 million.[16] 2.4.3 Public Services and Procurement CanadaThe Advertising Coordination and Partnerships Directorate of PSPC determines whether a project falls within the definition of advertising and assists departments and agencies in developing advertising statements of work. This directorate also advises departments and agencies whether draft creative materials, media buy strategies and plans comply with legislative and policy requirements.[17] Mr. Saint-Pierre told the Committee that PSPC provides departments and agencies with advisory and consulting services, as well as training, related to advertising. The Communication Procurement Directorate of PSPC is responsible for administering contracts for the procurement of approved advertising activities, including pretesting, production, media placement and evaluation. As well, the Public Opinion Research Directorate of PSPC advises departments and agencies and coordinates the pretesting and evaluation of advertising campaigns that have a total media buy of over $1 million.[18] Mr. Saint-Pierre explained that PSPC’s acquisitions branch is the contracting authority for the advertising services used by departments and agencies and as such, PSPC is responsible for the government contracting process for advertising and public opinion research. PSPC is responsible for administering the Advertising Management Information System and publishing an annual report on federal advertising activities.[19] It also coordinates with ASC the process for reviewing the creative materials for advertising campaigns.[20] Ms. Fox explained that PSPC acts as a liaison between departments and agencies and ASC during the ASC’s review process. Mr. Saint-Pierre added that PSPC is responsible for disseminating materials and best practices related to advertising. Lastly, he explained that PSPC manages the Agency of Record, which purchases the vast majority of advertising space and air time for departments and agencies subject to the policy. 2.4.4 Treasury Board SecretariatTBS approves requests from departments and agencies for new advertising funds and presents the amounts in the estimates for parliamentary consideration and approval.[21] It also has the delegated authority to amend or rescind the mandatory procedures related to the directive, including the Mandatory Procedures for Advertising.[22] As well, TBS annually reviews and makes the required amendments to the mandate, activities, terms of reference and criteria for the ASC review of non-partisan advertising for the federal government.[23] 2.5 Communications and Advertising

Under the Policy on Communications and Federal Identity, government communications must be objective, factual, non-partisan, clear, and written in plain language.[24] In the Directive on the Management of Communications, a communications product is defined as [a]ny product produced by or on behalf of the Government of Canada that informs the public about policies, programs, services and initiatives, as well as dangers or risks to health, safety or the environment. Communications products can also aim to explain the rights, entitlements and obligations of individuals. Communications products can be developed for a variety of media, including print, electronic and recording.[25] In addition, the directive defines advertising “as any message conveyed in Canada or abroad and paid for by the government for placement in media, including but not limited to newspapers, television, radio, cinema, billboards and other out-of-home media, mobile devices, the Internet, and any other digital medium.”[26] Ms. Baird cited this definition to the Committee. The federal government’s definition of a communications product and of advertising direct departments and agencies how to apply the requirements of the new policy and directive. Government communications encompass more than advertising.[27] Ms. Fox explained that “[a]dvertising is complementary to other activities.” And as she confirmed, the government intends to meet its commitment of reducing annual government advertising expenditures by $40 million by using both paid and unpaid communications to inform the public of its key programs and services. Dr. Marland echoed this view that advertising is often just one component of communications, and as he later added, “advertising in some ways should be the last resort, not the first thing you do.” He supports the idea that there is a balance to be achieved between the government’s use of communications tools and its advertising strategy. The testimony suggests that this relationship between communications and advertising should be considered when determining whether certain policies should be applied to content beyond the narrowly defined advertising activities of the government. As summarized by Dr. Rose in his brief, “The principle here is simple: there needs to be rules in place so that if and when a government’s good judgment lapses, they can be held to account.”[28] As explained by Ms. Baird, advertising is purchased space in a media outlet, which includes some social media. She said, however, that the government also uses social media for placements that are not paid, and that such placements would not be subject to the government’s standards on advertising. Similarly, she explained that a video that is produced and placed on a government website is not considered advertising under the advertising policy. Using another example, Mr. Saint-Pierre explained that a Health Canada billboard about “quitting smoking” that is posted on the Place du Portage government building is not considered advertising, whereas if the government paid to have the same billboard displayed elsewhere, such as along a highway, then it would be considered advertising. He later added that if a poster or sign was on an embassy outside of Canada, it would not be considered advertising. While Ms. Baird considers the definition of advertising clear, some witnesses thought it too narrow. Dr. Rose suggested that the definition of government advertising could be expanded beyond “paid” to also include “proposing to pay.” This would capture government sponsorship of an organization, such as a theatre, or a program, where the Government of Canada logo is displayed or advertised. Dr. Rose also suggested that the Committee look to other jurisdictions such as Ontario, whose pre-2015 policy mandated reasons for advertising. He commented that the definition could also be expanded to include government householders. 2.6 The Digital-First Approach

The federal government’s new communications policy has a “digital-first” approach. The federal government’s Web presence[29] and its official social media accounts[30] are the two main channels supporting this approach. According to Ms. Baird, “Canadians seek out their information through digital channels, and government now primarily interacts with the public through the Web and social media.” The requirement set out in the directive is that departmental heads of communications should be “[u]sing digital media and platforms as the primary means to connect and interact with the public while continuing to use multiple communications channels to meet the diverse information needs of the public.”[31] While several witnesses raised concerns about social media expenditures supporting businesses outside of Canada, Matthew Holmes, President and Chief Executive Officer for Magazines Canada, noted that there are ways for the government to focus digital media on Canadian sites. He suggested that online community newspapers and dailies and other digital-only platforms are a way to reach Canadians online. However, Mr. Jamison explained to the Committee that “[d]igital advertising revenues, which are tied to … news reporting, remain insignificant simply because community newspaper websites and social media feeds do not generate the traffic required to cover their reporting costs.” Ms. Fox told the Committee that social media is a tool that departments are using more frequently in order to reach remote communities. She added that “it’s really about identifying that target audience and using everything in [a government department’s] tool box to be able to support the community or support that group to raise awareness.” Thomas Saras, President and Chief Executive Officer of the National Ethnic Press and Media Council of Canada, suggested that if the government is advertising online, it does not reach certain ethnic communities that do not speak one of the two official languages. With respect to digital media, Dr. Rose highlighted that “[v]irtually all ads in traditional media of radio, print, and TV feature links to the Internet.” He added, “Without being able to scrutinize government websites, there is a potential for content that is laudatory, but that provides no information.” Both academics, Dr. Rose and Dr. Marland, suggested that the government should adopt a “first-click” rule that would apply government advertising standards to Web pages that are accessed from the “first click” of a link appearing on a government advertisement.[32] This change to the policy would ensure that those websites would be part of the advertising content review. Dr. Rose said that this is important because it would prevent government advertising from linking to content that does not adhere to government standards. Along those lines, Ms. Baird noted that “in media and communications, digital is influencing communications greatly and is changing all the time,” and that TBS would continue to monitor the government's definition of advertising with that in mind. 2.7 Support for Traditional Media

A concern raised by several witnesses from media associations is the challenge their members face with declining advertising revenues. Several witnesses told the Committee that print advertising is a major revenue contributor to community newspapers, and that most community papers are distributed free of charge. In his opening remarks, Mr. Jamison warned that “[c]ommunity newspapers face an uncertain future, as advertisers, including the federal government, have begun to rely more heavily on digital platforms to communicate key messages.” In particular, he noted that national advertising in community papers has experienced the greatest decline. Mr. Saras echoed these views: he said that as a result of declining government revenues, a number of ethnocultural publications have struggled or even been shut down. He called it a “crisis that affects not only the members of the ethnic publications, but also the mainstream media.” According to Mr. Holmes, the underlying economics of consumer magazine publishing in Canada have collapsed. Canadian print advertising spending has migrated to digital platforms, and digital advertising has, in turn, migrated offshore, largely to U.S.-based digital content distributors. Advertising revenues have decreased by half since 2007, from $732 million to $390 million. This decline has accelerated in the last four years by one-third. Several witnesses agreed that the federal government should support Canadian businesses through Canadian media advertising. According to John Hinds, President and Chief Executive Officer of News Media Canada, advertising in Canada's newspapers are not only effective, but they have the added advantage of strengthening Canadian businesses and Canada's communities. Mr. Jamison believes that the federal government has a role in supporting community newspapers. Along the same lines, Dr. Marland stated that “if we think about government as doing good things for the community, somewhere in all of this we have to balance the need for communications experts to focus directly on targeted messages with, at the same time, making sure our government is spreading public monies.” Several witnesses commented that the federal government has had an impact on the media industry in Canada, through policy and legislation, but also with its advertising revenues. On the topic of foreign content, one witness raised concerns about the protection of Canadian values when financial contributions and advertising from foreign governments are part of Canadian media. As an example, Mr. Saras noted that Italian-language publications published in Canada receive money from the Italian government. He added, “The same thing happens … with other governments and communities.” In his view, this allows foreign influence in Canada. 2.8 Committee Observations and RecommendationsThe Committee recognizes that it is highly important for government to communicate effectively and clearly with Canadians, especially on matters that directly impact them such as health and safety. It is of the opinion that Canadians must be properly informed about government programs and services. Information such as how to qualify for government programs and where to find answers to their questions is primordial. Thus, the Committee believes that the government’s new Policy on Communications and Federal Identity will help it to achieve these objectives. The Committee’s position is that government advertising must follow the same level of standards that apply to the private sector. It was therefore pleased to hear that government advertising is subject to the Canadian Code of Advertising Standards. The Committee commends the government for streamlining its policies and reducing its policy requirements related to government communications, as it believes having a single overarching directive on government communications facilitates understanding of the directive and conformity to it. Moreover, the various stakeholders will find a single directive easier to navigate. However, the Committee acknowledges that, because communications have rapidly evolved in the past decade, the policy and requirements surrounding government communications and advertising must be regularly updated. The Committee agrees that communications and advertising activities are complementary. It notes that the government should use a mix of both in order to effectively share information with Canadians. It observes that there could be some misalignment between the government’s digital-first strategy and the reality that many Canadians targeted by programs and services are best reached through more traditional media, including television, radio and print media. In addition, the Committee understands the concerns of some witnesses that the decline in the government’s spending on advertising in community newspapers and ethnic media has had a negative impact on those groups. Consequently, the Committee recommends that: Recommendation 1 The Government of Canada regularly update its policy and directive on government communications and advertising and ensure it remains relevant to address the challenges associated with continually evolving communications. 3.1 The Needs and Interests of the Public

The federal government defines the public as “[a]ll audiences, including employees of the Government of Canada and Canadians living or travelling abroad, who require information about Government of Canada decisions, policies, programs and services.”[33] Pursuant to the Directive on the Management of Communications, communications products and activities should be “[r]esponsive to the specific needs and interests of regional populations and multicultural and Indigenous communities.”[34] Further, the Mandatory Procedures for Advertising articulate a similar message – the requirement that “advertising activities consider the needs and interests of official language minority communities, as well as Indigenous and ethnocultural communities, as applicable.”[35] Identifying the needs of Canadians and how to reach a particular audience should be done in a holistic way, according to Ms. Fox. According to Dr. Rose, “citizens want to be invited to be part of the public conversation but too often they don't feel that they're part of that, and much of the government communication is really seen as self-promotion.” To that point, he questioned how Canadians could be engaged in more meaningful ways in order for them to have an incentive to follow government information. His main concern, however, is that government advertising should fulfil a strong public service goal, whether it be informing citizens of their rights or about services available to them, linked to a demand. According to Dr. Rose, the greatest need for government advertising is in the area of health care. With respect to sharing information with the public through government advertising, Mr. Hinds stated, “[W]hat we're looking for is engagement with Canadians about government programs and services in their communities.” Regarding a specific market, Denis Merrell, Executive Director of the Alberta Weekly Newspapers Association, said that the association “has a Statistics Canada database blended in with [its] newspaper circulation area so that [it] can actually target pretty well whatever demographic group the federal government is trying to reach, whether it be seniors, or according to spending on certain services.” He believes that this is something that could be helpful to the federal government. While some witnesses agreed that government advertising should be targeted to audiences based on the objectives of the advertisement, some expressed the view that the public should be able to see all government advertising. Dr. Marland gave the example of an online banner advertisement sponsored by the Government of Canada. He said that “it's important that all of us have a chance to see that banner advertisement, not only those of us who happen to be exposed to it through social media because of our particular demographics.” 3.2 Selecting the Appropriate MediaRegarding the needs of the public, Dr. Marland said that it is important to take a broader view of communications, of which advertising is one element. He argued that a good communications campaign uses all the different available forms of media, including direct marketing (traditional mail, telephone calls and email) and television or social media that repeat the message several times, to try to get the information to the appropriate individuals. In a written response submitted to the Committee, PSPC noted that the choice of media is at a department’s or agency’s discretion. On this topic, Mr. Saint-Pierre said that “media choices are based on a number of factors including: campaign objectives; target audience and market; type, time and scope of the campaign; budget; and the cost of the various media options.” Using the examples of notices regarding permits or endangered species, and advertising related to promoting tourism, agricultural support programs or recruitment, Ms. Fox pointed out that departmental advertising is most often local and targeted. Mr. Holmes proposed that the government include specific values in its advertising policy that address a requirement that advertising be placed with a diversity of media. He also suggested that there should be “some sort of assessment or benchmarking for the actual magnifier effect, the economic impact of that advertising that goes beyond just the audience.” Mr. Hinds stated that his organization believes that “the Government of Canada's advertising policy should reflect where Canadians look to find information about their community, and that newspapers, both print and digital, play a vital role in informing Canadians.” As for how the government can reach Canadians, he remarked: Almost nine in 10 Canadians read a newspaper every week, and that's up from five years ago. Six in 10 Canadians are reading print newspapers every week. Newspaper readership is now multi-platform, with three in 10 Canadians reading both print and digital formats. Even 85% of millennials are reading newspapers, with phone, of course, being their preferred platform. As well, Mr. Holmes cited a study that found that 93% of Canadians read magazines. Regarding meeting the needs of rural communities, according to Mr. Jamison, “Many Canadians, particularly those living outside major cities, continue to rely on their local community newspaper for important information.” To support this view, he made reference to a 2016 study which showed that of 2,400 Canadians surveyed, 83% were community newspaper readers, with 63% stating that they wanted to see advertising in their community paper. In a related remark, Mr. Merrell stated that in order to reach community newspaper audiences, which are largely rural, the federal government should “look at newspapers because they're the one medium that can really effectively reach 80% to 90% of those folks living outside the major centres.” Mr. Hinds remarked that Canadians trust advertisements that appear in newspapers and on news websites and said that the 2017 Reuters Institute Digital News Report notes that “eight out of 10 Canadians still consider traditional media and their brands among the most trustworthy sources.… Ads on social media, such as Facebook, and in search engines, such as Google, are among the least trusted.” He emphasized that this report also highlights that “only 18% of Canadians trust an ad on a mobile device, compared to almost 40% for a newspaper website.” As well, some witnesses commented that digital advertising may be ineffective in reaching Canadians who have limited access to broadband internet. Mr. Hinds said that “While 95% of Canadians in the highest income quartile are connected, only 62% of those in the lowest income quartile have [Internet] access.” According to him, reaching that target audience can present a challenge if the government is using digital media to advertise programs and services intended to meet the needs of Canadians in the lowest income bracket. Mr. Hinds suggested a “smart” government advertising policy that uses the appropriate medium to reach the people the government is targeting. He suggested, for example, that if the government is targeting seniors, it should look to newspapers. As for reaching small and medium businesses in Canada, Mr. Holmes commented that the government could target certain groups by industry and geography through advertising in business-to-business and farm magazines. As well, according to Mr. Hinds, newspapers can target businesses because 92% of business decision makers read newspapers, 71% of them print versions. According to Ms. Baird, the modernization of the communications policy keeps pace with how citizens communicate in a digital environment. She also acknowledged that, notwithstanding the shift to digital, some Canadians will continue to rely on traditional methods of communications and the government will continue to use multiple channels to meet the diverse needs of citizens. Several witnesses, especially those representing print media, suggested that this was not the case and that the decline in print advertising by the government was an indication that the government’s support for traditional media is also in decline. 3.3 Effectiveness of Government AdvertisingTo be effective, government advertising should be coordinated with other government communications. Ms. Fox explained that the government has “had campaigns where [it] did not reach the people [it] needed to reach” and for that reason, advertising “has to be complementary to other activities.” Concerning the creation of effective advertising, Ms. Fox explained that not all departments and agencies have the same capacities and that sometimes it is better to use firms outside government to get advice. She also commented that there could be “synergies” between departments and agencies, where talent and creativity could be shared, whether on a specific campaign or through an expertise network. According to Dr. Rose, government advertising can be useful if it provides a lot of information or if it informs citizens about services that are available to them. He suggested that the government should avoid “feel good” advertising. However, Dr. Marland highlighted the challenge of balancing government advertising as a way to provide information, and the effectiveness of that government advertising. He commented that with too much emphasis on government advertising as information, advertising can provide information that actually ends up not giving very good value for money. This, he said, was because, to be effective, an advertisement should try to provoke an emotional response or get people to pay attention to it. As well, Dr. Marland suggested that in order to be effective, government advertising should be simple and avoid too much detail. He explained the notion of “cognitive shortcuts” and “heuristics,” which, he said, “is using very few information processing abilities to quickly see things and make impressions.” He also noted the importance of repeating common elements consistently in advertising in order to influence audiences. He believes that the federal government should use the official colours of Canada, red and white, in all advertising. He explained, that the official government colours “should be everywhere, and everybody should be able to recognize that. It's very sensible from a brand point of view that if you see red and white, you think Government of Canada.” According to Dr. Marland, there is a “real incentive … for government to use the limited amount of money that they have on advertising to repeat common, consistent messaging.” In his view, advertising is otherwise “quite ineffective.” He suggested that “it would be useful to have advertising that promotes the fact that you can find information through the Government of Canada's information portal – just, generic, very high level, basic advertising that runs on a regular basis.” 3.4 Measuring the Effectiveness of Government AdvertisingAccording to the Directive on the Management of Communications, departmental heads of communications are responsible for using “the Government of Canada’s social media analytics and official Web analytics tool to evaluate and optimize the effectiveness of digital content.”[36] As well, the departmental communications branch must “[e]stablish performance indicators for advertising campaigns that have a total media buy of over $1 million.”[37] These campaign performance indicators and the related research results are shared with PCO. To measure the effectiveness of digital communications, the government can employ usability testing, often used as an analytics tool in the development of Web content, noted Ms. Baird. Ms. Fox told the Committee that “digital tools are allowing [the government] to do a lot of [shareable content] through social media.” With respect to online advertising, she noted that the average click-through rate[38] is 2%. For that reason, PCO considered the click-through rate of 8% for the Health Canada seasonal flu campaign a measure of success. Ms. Fox commented that the federal government is able to “have more metrics through digital.” She said that the successful Facebook advertising click-through rate – the industry standard – is about 1% and that PCO was able to measure the click-through rate for Transport Canada’s drone safety campaign at 2.73%. Stéphane Lévesque, Director General of Operations in Communications and Consultations at PCO, confirmed that the “clicks” and “click-through rate” data collected by the government is used to assess the impact of its communications and advertising activities, and for no other purpose. He later added that the data analytics from Facebook and Twitter posts that are collected are shared with some staff in order to help determine where to best place advertising, or communications. As for other metrics, Ms. Fox noted that “PCO works with departments on what tools are available to them.” She gave the example of a very local campaign, where the measure could be the number of applications received on a job posting, compared to a previous posting that wasn’t advertised. Ms. Fox pointed out that departments and agencies can purchase advertising for less than $25,000 directly, and she said that this helps them target a very specific audience, through a particular publication or tool. Regarding evaluations, Ms. Fox explained that campaigns with a value of $1 million and above involve a “full mandatory evaluation” but that PCO encourages departments to look at evaluation methods and results for all campaigns, regardless of their size. She added that departments often submit information on results and data for smaller campaigns to PCO through other mechanisms. For example, she said that they could be provided as part of a business case supporting a particular campaign or approach that was effective in the past. Although there was some discussion of metrics for digital campaigns, there was little said about how the effectiveness of traditional campaigns is measured. According to Dr. Rose, “we really do not know how effective advertising is in influencing the attitudes and behaviours of citizens.” 3.5 Committee Observations and RecommendationsThe Committee acknowledges that the federal government may not be effectively reaching Canadians with its increased use of digital media for advertising, a point raised by some witnesses. The Policy on Communications and Federal Identity directs departments and agencies to determine which media channels to use depending on their target audience. Based on what it heard, the Committee is concerned that the government’s “digital-first” approach and its commitment to significantly reduce advertising expenditures might limit the choice of media – favouring digital media over perhaps more costly traditional media. Therefore, the Committee believes that the government should increase advertising in weekly, multicultural and community newspapers, magazines and other local media. In addition, it encourages the government to pay closer attention to selecting the appropriate media, in order to successfully reach the target audience for a particular advertising campaign. The Committee feels there is limited information on the effectiveness of government advertising and that the government lacks the means to properly evaluate the impact of its communications and advertising on Canadians. Therefore, the Committee questions whether the federal government is effectively reaching Canadians through its communications and advertising activities. Consequently, the Committee recommends that: Recommendation 2 The Government of Canada increase advertising purchasing for weekly, multicultural and community newspapers and other local media, so that the government meets the stated directive that communications are responsive to the diverse information needs of the public. Recommendation 3 The Government of Canada ensure that the medium of government advertising appropriately reflects the target audience. Recommendation 4 The Government of Canada explore having departments and agencies establish performance indicators to evaluate the effectiveness of advertising activities for all advertising campaigns, similar to those in private industry, involving both traditional media and digital media, and that the results of these evaluations be publicly reported through its annual report on advertising. 4.1 Non-Partisan Communications

Among the changes designed to address partisanship in the Policy on Communications and Federal Identity, there is the following definition of the term “non-partisan communications”:

Dr. Rose commented that the most significant change in the policy is the banning of partisanship and further noted that the definition of the term “non-partisan communications” includes elements on which people can agree. However, he highlighted that with the exception of the first point – “non-partisan” means objective, factual and explanatory – the definition focuses on the absence of things and qualified it as a negative definition. Ms. Baird emphasized that all government communications activities must be non-partisan and she specified that this includes ministers’ speeches and videos of them. Ms. Fox added that “[a]ll Government of Canada activities, whether Web presence, a news release, or a social media shareable, [abide] by non-partisan communications standards.” In response to a question from a Committee member, Ms. Baird said that the last element of the definition relates to senators and members of Parliament and is being followed. Some Committee members voiced concerns about the use of the Canadian colours by political parties and in government advertising. On the use of those colours, Ms. Baird responded that there are some exceptions such as the Canadian flag and the uniform of the RCMP, which are red and cannot be changed to another colour in an advertising campaign. However, she pointed out that 4 of 1,800 advertising pieces submitted to ASC for review were modified after ASC questioned their dominant use of the colour red, which she said is proof that the current review process is working. Additionally, Ms. Baird explained that even if there are different shades of red and specific colour shades are used on government websites, “to the average Canadian, some of that distinction is lost.” She said that this is the reason why government officials do not look at specific shades of red, but rather at the red colour generally, in evaluating whether its use is appropriate. Ms. Fox specified that “[o]n the government websites, all communication would have to adhere to the colour requirements for the communications policy.” As previously discussed, Dr. Marland suggested using the Canadian colours in government advertising. He acknowledged that these colours are also used by some political parties at different levels of government, and he suggested that, in order to ensure that there is no confusion between a political party and the government, political parties be prevented from using the official colours of the Government of Canada. He came to the conclusion, however, that this suggested solution would be very challenging to implement and therefore Canadians and governments have to contend with the fact that some political parties use the Canadian colours. In an answer to a question from a Committee member, Dr. Marland explained that the solution is not to restrict political parties from using Canadian colours since too much regulation is not optimal and could prevent people from communicating. Moreover, he highlighted that the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms should be taken into account when exploring potential solutions. Dr. Rose suggested that the policy include positive standards or goals to which government advertising must adhere. He noted that before it was amended in 2015, the Province of Ontario’s Government Advertising Act, 2004,[39] was a good model, as it placed the burden on the government to defend the need for an advertising campaign. In addition to being non-partisan, all government advertising in Ontario “had to inform the public of policies or services, inform about rights, or encourage or discourage social behaviour in the public interest.” The Act also permitted the Auditor General of Ontario to review government advertising for context, but this was removed in 2015. With respect to partisan advertising, Dr. Rose expressed the view that the context of advertising is crucial in the assessment of its non-partisanship. He explained that “[s]ometimes a perfectly appropriate government ad can be supplemented by a political party ad that communicates the same thing. In those cases, the government ad is a thinly disguised attempt to leverage party advertising through government advertising.” He encouraged the Committee to consider addressing political party advertising that piggybacks on government advertising, but he mentioned that all parties, when governing, campaign on what they have accomplished. On that point, Dr. Marland noted that some governments attempt to combine information in a way that makes it difficult to distinguish between government advertising and political advertising for the governing party. In his book, Brand Command, he suggested the creation of a political communications code of ethics that “should act as a moral compass for political actors who have different interpretations of the boundaries of freedom of speech.”[40] In analyzing the appropriateness of advertising, Dr. Marland suggested that the government should consider the concept of “policy.” He noted that, for example, advertising to Canadians about a health pandemic is about information, whereas other types of advertising that inform Canadians about a government policy could be seen to be highlighting something that was inherently political. On the other hand, Dr. Rose explained that in those cases, it would be appropriate for members of Parliament and others – and not government – to persuade citizens about the benefits or drawbacks of a particular policy. Dr. Marland suggested eliminating financial support from taxpayers or any private donors for debranding or negative advertising “without people’s specific, explicit knowledge that money is going in that direction.” He explained in Brand Command that “[e]xcessive negativity and debranding are harmful to civic discourse and public engagement in a democratic system of government.”[41] He voiced concerns about the fact that money spent on advertising during an election campaign “is essentially subsidized by taxpayers, either through the fact that donations to political parties are tax deductible, or because a portion of the spending is returned after the fact if you meet certain thresholds.” Therefore, in his book, he suggested that political donations be subject to a less generous tax refund scheme.[42] Commenting on negative advertising, Dr. Rose informed the Committee that “studies in the United States have shown there is more information found in negative advertising than in positive advertising. There are more lies in positive advertising than there are in negative.” Finally, Dr. Marland advocated for the development and the maintenance by a third party of a form of checklist to assess whether government advertising is appropriate and non-partisan. In his view, such a checklist would enable Canadians to readily assess whether a government advertisement is political or partisan and could expand on the basic framework laid out in the Ontario Government Advertising Act. Both Dr. Marland and Dr. Rose said that this checklist would encourage informed judgment, which according to Dr. Marland could lead to self-regulation by the federal government. 4.2 Ban on Government Advertising During ElectionsSection 6.45 of the Directive on the Management of Communications provides that heads of communications are responsible for “suspending advertising activities 90 days prior to a fixed general federal election date.” Furthermore, the directive defines the term “advertising activities” as “[a]ctivities related to producing and placing advertising, including campaign planning, creative development, pretesting, production, media planning, placement of advertising and evaluation.” Dr. Rose clarified that the ban on government advertising excludes job advertisements, requests for tenders and messages to the public regarding urgent matters affecting public health and safety. Commenting about this 90-day ban, Dr. Rose observed that it is an important improvement. He pointed out that, however, according to his research, governments tend to spend more on advertising in the year preceding an election, which means that the 90-day ban might have little effect. In addition, he indicated that there is no rule restricting government advertising during by-elections. In his view, the logic used for general elections should apply to by-elections and consequently he urged the government to consider banning government advertising during by-elections. In a brief he submitted to the Committee, he explained that during the 41st Parliament, which was in place from June 2011 until August 2015, there were 15 by-elections clustered around 4 dates. While Dr. Marland agreed with this suggestion, he said that a cost-benefit analysis of advertising campaigns would be helpful as it is unknown how effective government advertising is in the first place. He added that by-elections are often outside governments’ control and said that the government might want to establish a threshold for the number of by-elections taking place at the same time or within a given period above which government advertising would be banned. However, Dr. Rose argued that the government could change its behaviour and cluster by-elections in order to avoid a by-election threshold. Dr. Rose informed the Committee that two provinces – Manitoba and Saskatchewan – limit government advertising during by-elections. Manitoba prohibits government advertising during the 90 days before by-elections. Saskatchewan bans such advertising during the election period, which is fixed at 27 days, and for 30 days before the election period. It also allows only advertising that provides information on government programs and during the 90 days before the election period. Finally, it prohibits spending more on advertising during the 120 days before an election period than it did during the same time frame the previous year. Dr. Rose also said that modern communications are not bound by electoral districts and therefore, restricting government advertising to a specific electoral district and the surrounding ones during a by-election is meaningless. Moreover, he added that, according to some studies conducted on government advertising, government spiked its spending on advertising a year before an election and that party advertising during an election is mostly short-term and largely aimed at confirming existing beliefs, as opposed to negating them. 4.3 Committee Observations and RecommendationsThe Committee is pleased to see a definition for "non-partisan communications" in the Policy on Communications and Federal Identity and furthermore believes that this definition should be regularly reviewed to ensure that it remains relevant and up to date. The Committee supports the principle that all government communications, including ministers' speeches and videos, be non-partisan, because its position is that the governing party should not use public resources and taxpayers’ money to promote a political agenda. The Committee recognizes that the Canadian colours have been used for decades by political parties at all levels of government and that they cannot be modified in government advertising because they are important elements of the government trademark, and it agrees with some witnesses that it is a reality with which governments have to contend. It believes, however, that special attention must be given to the employment of these colours in the development and review of all government advertising to ensure an appropriate and justified use. Regarding by-elections, the Committee believes that, because of their frequency, it would be difficult to treat by-elections as general elections and impose ban on government advertising for the 90 days preceding them in the affected electoral districts and surrounding areas. However, it is of the opinion that the government should be more cautious with its advertising campaigns during by-election periods and, where possible, make use of third-party oversight of its advertising during these periods. Consequently, the Committee recommends that: Recommendation 5 The Government of Canada regularly assess and review its definition of the term "non-partisan communications" and update it as required. Recommendation 6 The Government of Canada require that, where possible, all advertising campaigns be reviewed by a third party during by-elections to ensure non-partisan advertising.

5.1 Role of Advertising Standards CanadaASC is a not-for-profit body that reviews Canadian advertising against legislative and regulatory requirements and administers the Canadian Code of Advertising Standards. Jani Yates, President and Chief Executive Officer of ASC, explained to the Committee that ASC helps to ensure that advertising in five regulated categories [children’s advertising, alcohol, food and non-alcoholic beverages, cosmetics, and consumer-directed non-prescription drugs] complies with the government requirements affecting advertising, as well as specific industry codes and guidelines. Regarding government advertising campaigns with budgets over $500,000, ASC reviews against the established criteria for non-partisan communications all creative materials, in English and French, prior to distribution, posting or publication of advertising.[43] In response to a question from a Committee member, Ms. Baird explained that the mandatory review process is based on the total budget of government campaigns and that therefore anything that falls within one campaign cannot be split in order to circumvent this review. Advertising campaigns under $500,000 are not subject to mandatory non-partisan review by ASC. However, they can still be sent for review on a voluntary basis. In response to a question from a Committee member, Ms. Baird indicated that so far two advertising campaigns with a budget value below $500,000 had been voluntarily submitted to ASC for review. Ms. Baird explained that the $500,000-threshold was established because about 90% of government advertising campaigns were over that amount during the three-year period that was analyzed. However, she did not share the specific years of that period. In her view, this threshold is a “good balance between having the third party oversight on as many [advertising campaigns] as possible and taking into consideration cost, volume and work.” She added that “[s]ome of the lower-dollar campaigns include the digital ones because those are less expensive ways to advertise. Often they have multiple creatives because they're different sizes and have many different placements, so the volume is actually quite high for a similar creative.” On that point, Mr. Saint-Pierre indicated that two years ago, the federal government spent between $4 million and $5 million on public notices such as notices of the temporary closure of a bridge and most of the notices cost under $2,000 each. In response to a question from a Committee member, Ms. Baird said that around 50 advertising campaigns, or less than 20% of all advertising campaigns, were not reviewed by ASC in 2016–2017. Regarding the $500,000 threshold, Dr. Rose indicated that based on the cost of advertising in traditional media, $500,000 is a reasonable amount, but he said that the increasing presence of digital media and their reduced costs should “raise some flags.” In order to address this challenge, he suggested either changing the culture of government departments and agencies to encourage them to voluntary submit all their advertising campaigns to ASC for review or revising the threshold amount in order to take into account both the trend towards the use of digital marketing and other elements, such as ethnic media. ASC’s review results and decisions are published on the Government of Canada website. However, announcements of an administrative or operational nature – such as public hearings, employment offers, notices of public consultation, requests for tenders or changes to office business hours, and messages to the public regarding urgent matters affecting public health and safety or the environment – are not reviewed.[44] Ms. Baird indicated that ASC reviews are conducted “at two stages: an initial one, done in the planning stages with concepts and story boards; and a final review, done prior to the advertising going to market.” She added that at the end of every ASC review, a report about the review is posted publicly on the Government of Canada’s website. Moreover, during the ASC review process, “should there be a disagreement, the matter will be referred to the secretary of the Treasury Board for resolution” and that “[t]o date, there have been no disagreements with the reviews.” Finally, she told the Committee that ASC carries out the reviews through a contract with the federal government and that TBS meets regularly with PSPC and ASC in order to discuss the review process and operational issues. Ms. Yates mentioned that the federal government asked ASC in 2016 to review government advertising and that ASC undertook 1,800 reviews during that first year. She added that ASC recently signed a second-year contract with the federal government that will end on 31 March 2018. In response to a question from a Committee member, Ms. Baird said that the value of the contract with ASC was $65,000 plus the Harmonized Sales Tax (HST) for the first year and $73,000 for the second year. Dr. Rose noted that although ASC is an excellent organization for monitoring and regulating commercial advertising, many of the 14 criteria of the Code it administers do not pertain to government advertising. For example, government advertising would not include deceptive price claims or bait and switch. Furthermore, he commented that ASC’s discretion is limited and advocated providing this independent review body with greater latitude and with appropriate means to hold the government to account.[45] He also suggested that the federal government emulate the Government of Ontario and consider the “first click” – in digital media, the first advertising hyperlink clicked by users, and in traditional media (i.e., radio, print and television), featured links to the Internet – to be part of the advertising and thus subject to review by ASC. In his view, if these websites are not subject to review, they could “serve as a way to drive traffic to a government website that does not adhere to the [non-partisan] criterion.” 5.1.1 Complaints ProcessASC manages a complaints process under which consumers can ask ASC to review advertising that they believe does not comply with the Code. Once a complaint is received, ASC conducts a preliminary review of the complaint to ensure that “based on the provisions of the Code reasonable grounds for the complaint appear to exist”[46] and sends an acknowledgment to the complainant. Then, ASC refers the matter to one of the two councils, the Standards Council of Canada[47] or le Conseil des normes in Quebec, for adjudication. Although these two councils include industry and public representatives and are supported and coordinated by ASC, they act as independent bodies.[48] If during the complaint review process and before the Council’s decision on the complaint, either ASC or the Council believes that the complaint is not a consumer complaint, but rather a trade complaint or a special interest group complaint, the process will be abandoned.[49] Moreover, the complainant will be notified that the complaint should be registered either under the ASC’s Advertising Dispute Procedure, which deals with advertising complaints between advertisers, or under the ASC’s Special Interest Group Complaint Procedure, which addresses advertising complaints from special interest groups. In a response to a question from a Committee member, Janet Feasby, Vice-President of Standards at ASC, explained that ASC reviews all complaints whether it is a government or a private advertising under the Code. She added that “[i]f a complaint is alleged about permanent advertising that falls under the Code, then [ASC] would review it under one of [its] 14 clauses. If a complaint alleges that an ad is partisan, that's something [ASC] would forward to the government to deal with.” 5.2 Appropriate Oversight Mechanisms and Transparency